KATHMANDU: On September 21, 2004, a royal palace staff member arrived hurriedly at the Dillibazaar Land Revenue Office with a sealed envelope bearing the official palace stamp. Without hesitation, he approached the head of the office and declared, “An order has come from the palace. It must be implemented immediately.”

Once the letter was registered, the staffer quickly returned. At the time, Tikaram Ghimire was serving as the chief officer of the Dillibazaar Land Revenue Office. Upon being informed of the palace directive, Ghimire hurriedly opened the letter.

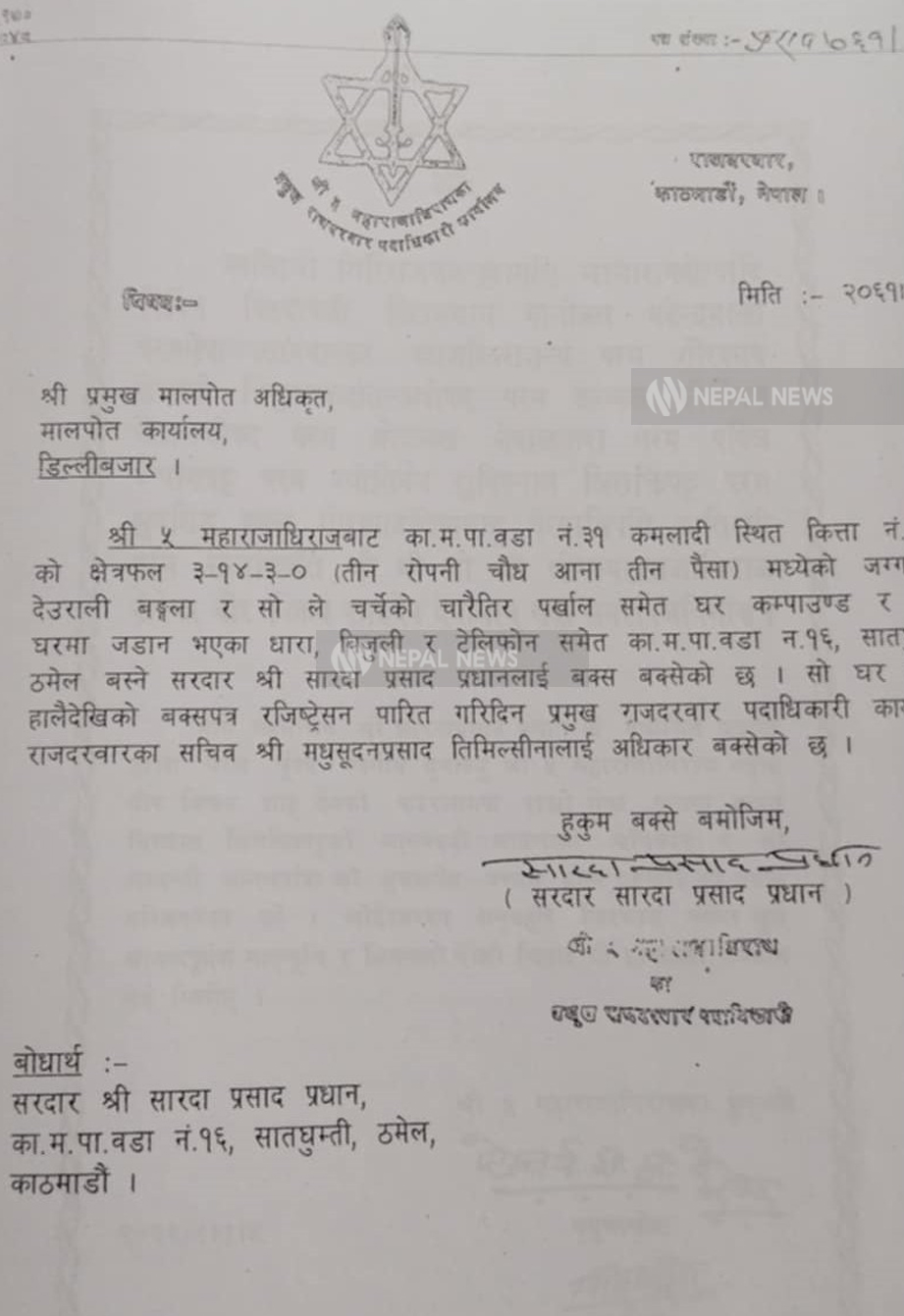

The contents were clear: “From the Shree Panch (His Majesty the King), the land located in Kathmandu Ward No. 31, Kamaladi — Plot No. 364, covering an area of 3 ropani, 14 aana, and 3 paisa, including the Deurali Bungalow, its surrounding compound walls, and all utilities (water, electricity, telephone) connected to the property — is to be granted to Sardar Sharada Prasad Pradhan, resident of Satghumti, Thamel.”

Essentially, the royal letter ordered that a valuable piece of land in Kamaladi — measuring over 3 ropani and including a well-known property– be transferred into private ownership, in the name of a palace official.

Sardar Sharada Prasad Pradhan was the head of the Royal Expenditure Department during King Gyanendra’s active regime. The letter sent from the palace, however, bypassed legal procedures. The irregularity came to light years later, when the Nepal Trust began the process of transferring the late King Birendra’s properties into public trust ownership in 2018.

Today, Pradhan’s sons are challenging the government’s move. They’ve filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court, claiming that their right to personal property has been violated. But even after seven years, the case—filed in 2018—remains unresolved. It has been listed as “not open for hearing” eleven times.

What’s the dispute?

Kamaladi is among the most expensive areas in Kathmandu. At the time in question, land prices there had reached as high as Rs 20 million per aana. Within the parcel in question stood the iconic Deurali Bungalow.

Sardar Sharada Prasad Pradhan had submitted a request to the Land Revenue Office to register 14 aana of that land, along with the house built on it, in his own name. The letter from the palace, authorizing the transfer, caused a stir among the land office employees. Who, during the height of King Gyanendra’s direct rule, would dare question the legitimacy of a royal order?

“That was a very difficult time,” recalls Tikaram Ghimire. “I remember being pressured even by people falsely claiming to be palace relatives.”

According to Ghimire, instructions were given to finalize the registration within days. “But that wasn’t legally possible,” he explains. “Sharada Prasad himself had submitted a letter requesting the land, which made the situation even more questionable. We held several internal discussions, but the pressure from the palace kept mounting.”

In the letter to the Land Revenue Office, Pradhan had not only referred to the royal grant but had also explicitly written his own name and address—making his personal interest in the matter very clear.

Letter sent by Sharada Prasad Pradhan of the then Royal Palace’s Expenditure Department submitted to the Dillibazaar Land Revenue Office, requesting that 14 annas and three paisa of land be transferred to his name.

After growing pressure from the royal palace, officials at the Dillibazaar Land Revenue Office finally moved to formalize the transfer of valuable land in Kamaladi. “We prepared the legal paperwork in a matter of days and sent it to the royal palace,” recalls Ghimire, who was then the chief land revenue officer.

The documents confirmed that the land was officially registered in the name of Sharada Prasad Pradhan on September 21, 2004. On the same day, the Land Revenue Office had written to the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, asking for an immediate evaluation and processing of the registration sponsorship. The city’s revenue department responded by waiving the requirement for immediate valuation and exempting the property from taxation.

A new bungalow rises

Shortly after acquiring the land, Sharada Prasad demolished the existing structure—the Deurali Bungalow—and built a new one. According to records, the Mapping Section of the Urban Development Department granted him a permit to construct a three-and-a-half-story residential building on March 17, 2005. Within six months, the city issued a completion certificate.

The location was prime: Tukucha River to the east, a road to the west, and royal property to both the north and south. The proximity to the Narayanhiti Palace—just an eight-minute walk from its southern gate—meant the new bungalow, built by Sharada Prasad, became an informal gathering place for members of the royal family. After Sharada Prasad passed away on May 4, 2009, ownership of the land and house was transferred to his children.

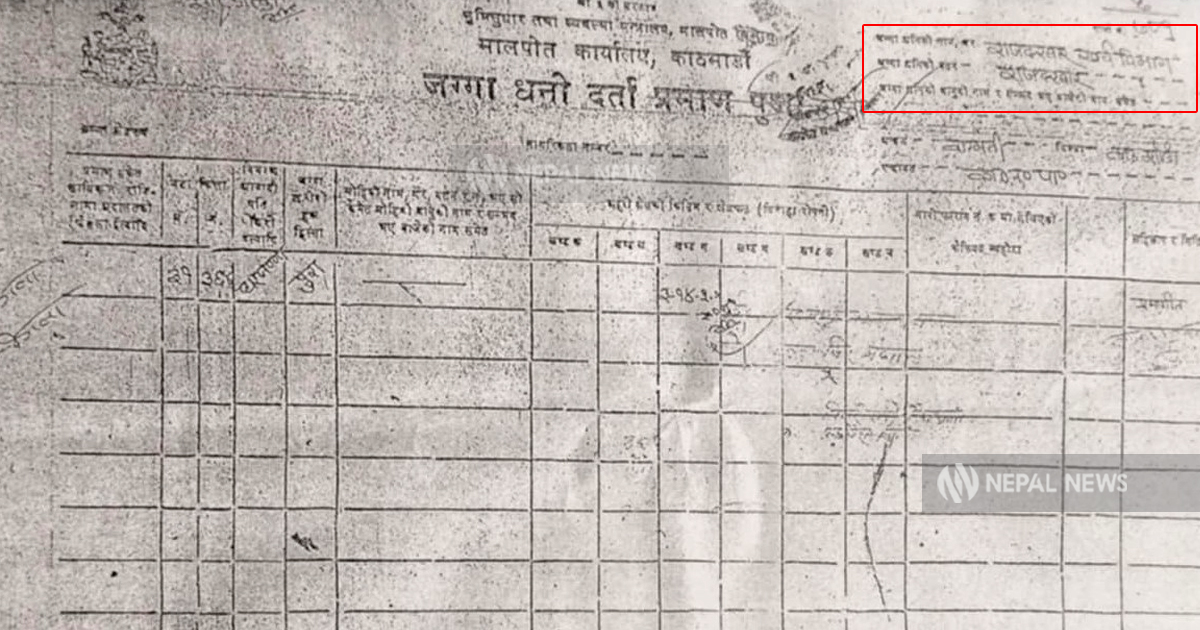

Land ownership certificate of Diyalo Bungalow in the name of the then Royal Palace.

The Nepal Trust steps in

Following the fall of the monarchy after the 2062/63 BS (2006) People’s Movement, the government established the Nepal Trust to manage and reclaim properties that had belonged to the royal family. The case of the Deurali Bungalow surfaced during the Trust’s investigation, which began on November 22, 2007.

At first, officials at the Trust were incredulous. “We couldn’t believe that such valuable land in Kamaladi had been quietly transferred to an individual,” says Yadu Prasad Panthi, the then Joint Secretary of the Nepal Trust. “It wasn’t a sale. There were no official documentation from Raj Prasad Sewa. How could royal land end up in someone’s name based solely on a letter from the Royal Expenditure Department?”

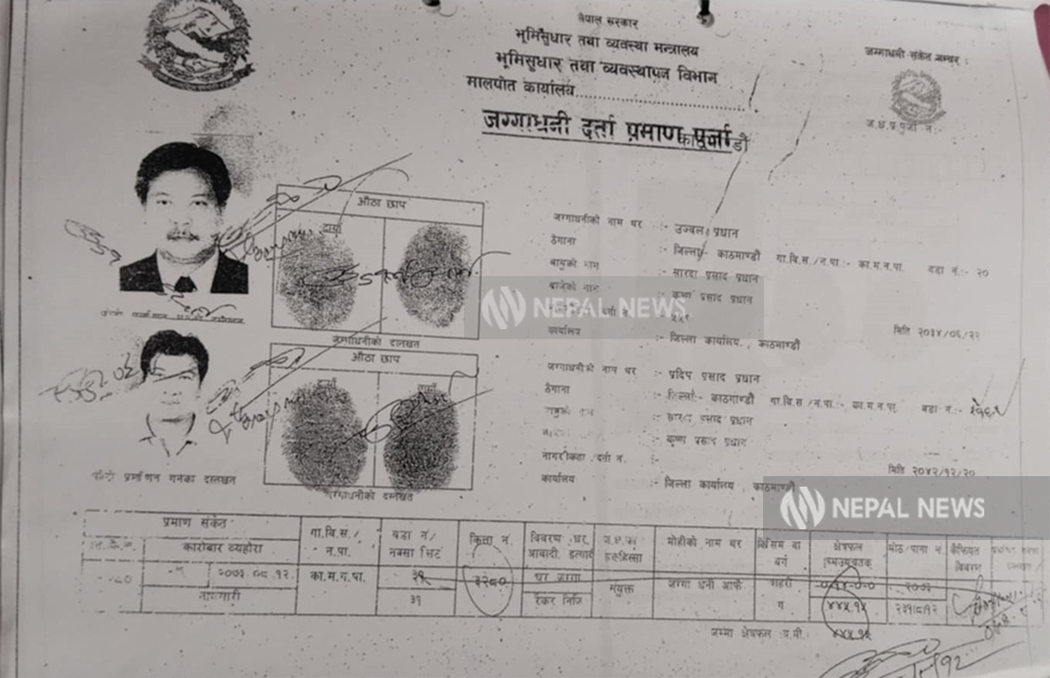

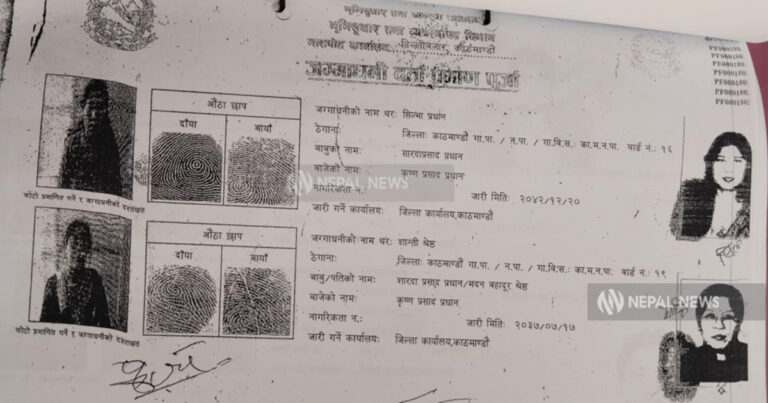

Land ownership certificate transferred by Sharada Prasad Pradhan to his sons.

Panthi and his team began an exhaustive review of land records, survey documents, and palace files. Their investigation revealed that the property had indeed been transferred illegally—no formal decision had been made, and the land had simply been granted to an individual through forged or unauthorized paperwork.

With the evidence in hand, the Council of Ministers convened on November 11, 2018 and issued a directive: the land must be returned to state ownership under the Nepal Trust. The decision was based on the finding that the land was never private property, but had belonged to the late King Birendra and his royal family.

Acting on the decision, the Nepal Trust sent an official letter to the Dillibazaar Land Revenue Office on November 16, 2018 , stating: “The land was transferred to the name of Sharada Prasad Pradhan on 2061.6.4, while it remained registered under the Royal Palace Expenditure Department until 2061.4.5. On November 27, 2016, it was further transferred to his sons, Ujjwal Pradhan and Pradeep Pradhan, who are currently listed as owners. Kathmandu District, Kathmandu Ward No. 31, Plot No. 3280, Area 0-14-0-0 Ropani — this land must now be registered under Nepal Trust as per the Council’s directive. Kindly issue the updated landowner document.”

Property ownership certificate of land transfer by Sharada Prasad Pradhan to his daughters.

Following this correspondence, the land—more than three ropani in one of Kathmandu’s most expensive neighborhoods—was officially reclaimed by the Nepal Trust.

After years of legal battles and government orders, the land where the historic Deurali Bungalow once stood is now officially in the name of the Nepal Trust. But despite this transfer, the property—located on some of Kathmandu’s most valuable land—remains unused. And it remains at the center of an unresolved legal tug-of-war.

As soon as the land was transferred to Nepal Trust, eight individuals, including Jayanti Shrestha, daughter of the late Sharada Prasad Pradhan, filed a writ petition at the Supreme Court. Their core argument: the property was taken without due notice or legal process.

“This land has been in our name for decades. Transferring it to Nepal Trust without notifying us violates our rights to private property,” the petition reads. “The decisions made by the Government of Nepal (on November 11, 2018), the Prime Minister’s Office (November 14, 2018), and the Nepal Trust Office (on November 16, 2018) must be declared void.”

A gift to oneself?

The controversy began with Sharada Prasad Pradhan, who once served as chief of the Royal Expenditure Department during King Gyanendra’s direct rule. It was Pradhan himself who sent a letter to the Land Revenue Office claiming he had received the land as a “gift” (bakas).

This immediately raised legal and ethical questions: Can someone give themselves a gift box? While Nepali law does allow individuals to gift property to others, gifting state or royal property to oneself is murky—and potentially illegal. Under Section 406(2) of the Civil Code 2074 BS, a gift is defined as property transferred without charge to another person out of affection, reward, or other motives.

However, former Supreme Court Justice Balaram KC says the law is clear in this case: “Giving yourself royal property as a gift and registering it in your own name is illegal—especially if that land was supposed to go to the Nepal Trust.”

The land in question, originally registered under the Royal Palace’s Expenditure Department, was later transferred to Pradhan’s name and then inherited by his children. Today, the land is valued at approximately Rs 280 million.

Multiple writ petitions have been filed challenging the government’s decision to transfer the land to the Nepal Trust. The main case—filed in the name of Jayanti Shrestha—has seen 22 scheduled hearings, of which 11 were not even opened for review.

Despite the delays, the Supreme Court has taken some steps. On December 5, 2018, a bench led by then-Chief Justice Deepak Raj Joshi issued a show cause order. On December 12, 2018, Justices Hari Krishna Karki and Sapana Pradhan Malla directed the case file to be sent forward. Later, on February 17, 2025, Justices Nahakul Subedi and Nityananda Pandey ordered the file to be tabled again. But despite these motions, the case remains undecided, years after it was first filed.

A precedent from the Crown Princess

This isn’t the first time royal land ownership has been contested in court. In a closely watched case, former Crown Princess Prerana Rajya Laxmi Devi Singh challenged the Nepal Trust’s claim over 15 ropani and 1 anna of land in Tahachal, which she said had been gifted to her as dowry by her father, former King Gyanendra Shah. Initially, the court agreed with her. A bench led by Chief Justice Ram Kumar Prasad Sah and Justice Cholendra Shumsher Rana ruled that the land was her dowry and therefore her personal property.

However, the Nepal Trust appealed, and a full bench—comprising Chief Justice Sushila Karki, and Justices Sapana Pradhan Malla and Deepak Kumar Karki—overturned the previous verdict. Their ruling was categorical: “No individual can claim private ownership of land that legally belongs to the state or the former royal family and is intended for public trust.”

Though there was a legal path for the Crown Princess to escalate the case to a larger full bench, she instead approached the Constitutional Bench, which included some of the same justices from the earlier decision. Led by Chief Justice Cholendra Shumsher Rana, who had originally ruled in her favor, the Constitutional Bench changed course and dismissed the writ on February 7, 2020.

This landmark decision officially placed the Tahachal land under the Nepal Trust, setting a strong precedent for similar disputes—like the one now unfolding over the Deurali Bungalow.

Legal battle far from over

A high-ranking official at the Nepal Trust Office believes the case of the Deurali Bungalow is essentially a mirror of the Prerana Singh case—and should reach the same conclusion.

“You cannot claim personal rights over royal or state property just because you managed to register it in your name during a favorable political environment,” the official said. “This land legally belongs to the Nepal Trust.”