Only three became law in 32 years

KATHMANDU: Since 1991, only three out of the 79 non-governmental bills registered in Parliament have acquired legal status. The Constitution gives Members of Parliament the right to register private bills on issues other than finance and national security. In practice, however, since the government remains decisive, this right has not been effective. While even government bills struggle to become law, the condition of non-governmental bills has been miserable.

The latest non-governmental bill in Nepal’s parliamentary history is the ‘Discrimination on the Basis of Caste, Color, Region, Dress, Nationality or Origin (Offences and Punishments) Bill, 2025’. It was registered on February 3, 2025, by CK Raut, Chair of the Janamat Party and a Member of the House of Representatives.

The bill states that discrimination based on caste, region, color, nationality, or origin undermines the constitutional rights to equality, freedom, and dignity. To eliminate such discrimination, the bill proposes defining discrimination, creating provisions for punishment, and ensuring legal remedies and compensation for victims.

At a time when even government bills find it difficult to obtain legal form, it is not surprising that non-governmental bills have made no progress beyond being distributed as copies to lawmakers.

A similar fate befell the ‘Human Body Burning Control and Punishment Bill, 2024’. The bill was registered in the House of Representatives on August 15, 2024, by fourteen lawmakers led by Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) parliamentarian Bindabasini Kansakar.

Sadly, the bill has not even undergone a general discussion yet. MP Kansakar complains that despite repeatedly raising the issue with the Finance Minister and the Law Minister, she has received no positive response. “We spoke with the Finance and Law Ministers. They have shown some interest, but there is still no clarity on when the bill will move forward,” says Kansakar, herself a burn survivor.

The bill proposes measures to reduce incidents of natural burns, punish those involved in criminal burn cases, create an environment for burn survivors to live with dignity in society, provide compensation, necessary rescue, treatment, relief, and employment opportunities according to their qualifications. The bill also mentions the need for a special financial relief fund, as burn victims—mostly from poor and marginalized communities—face greater suffering in the absence of proper laws.

How bills originate

Bills usually originate in two ways: as government bills registered by departmental ministers, or as non-governmental bills registered by lawmakers. According to data from the Parliament Secretariat, since the 1991 general election, a total of 79 non-governmental bills has been registered.

A 2023 report titled ‘Practice of Private Bills in Nepal’ by the Parliament Secretariat notes that between 1991 and 1994, 26 private bills were registered in Parliament, but none became law. Between 1994 and 1999, 19 private bills were registered, of which three became law. Between 1999 and 2002, 12 private bills were registered, but none were enacted as law.

The ‘fortunate’ three bills that became law

“Until now in parliamentary history, only three private members’ bills have successfully passed the legislative process and become law,” says Parliament Secretariat spokesperson Ekram Giri.

Bills usually originate in two ways: as government bills registered by departmental ministers, or as non-governmental bills registered by lawmakers. According to data from the Parliament Secretariat, since the 1991 general election, a total of 79 non-governmental bills has been registered.

One such ‘fortunate’ bill was the Human Rights Commission Bill, 1995’ registered by MP Mahesh Acharya. “At that time, Manmohan Adhikari of CPN-UML was Prime Minister. Many felt the need for a human rights body, so I registered the bill,” recalls former MP Acharya. “Public opinion was in favor of the bill, not just within the Nepali Congress parliamentary party but also outside. With everyone’s support, the bill was passed,” he adds.

In addition, the ‘Nepal Health Professionals Council Bill, 1997’, registered by MP Dr. Shankar Prasad Upreti, and the ‘Legal Aid Bill, 1997’, registered by MP Subash Chandra Nembang, also succeeded in becoming law.

The very first private member’s bill ever registered in parliamentary history was the ‘Marriage System and Provisions for a Woman’s Right Regarding Marriage, 1954’. It was introduced by MP Tara Devi Sharma during the period of the ‘Nepal Interim Government Act, 1951’.

According to the Federal Parliament Secretariat, Sharma registered the first non-governmental bill in the Second Advisory Assembly. The bill contained provisions against child marriage, polygamy, and mismatched marriages prevalent in society at the time. “Although the bill was registered, there is no record of what happened afterward,” notes the ‘Practice of Private Bills in Nepal’.

Government remains decisive

Article 110 of the Constitution of Nepal outlines provisions related to bills. Clause 2 of that Article states, “Bills relating to finance, the Nepal Army, the Nepal Police, or the Armed Police Force, Nepal, and other security bodies shall only be introduced as government bills.”

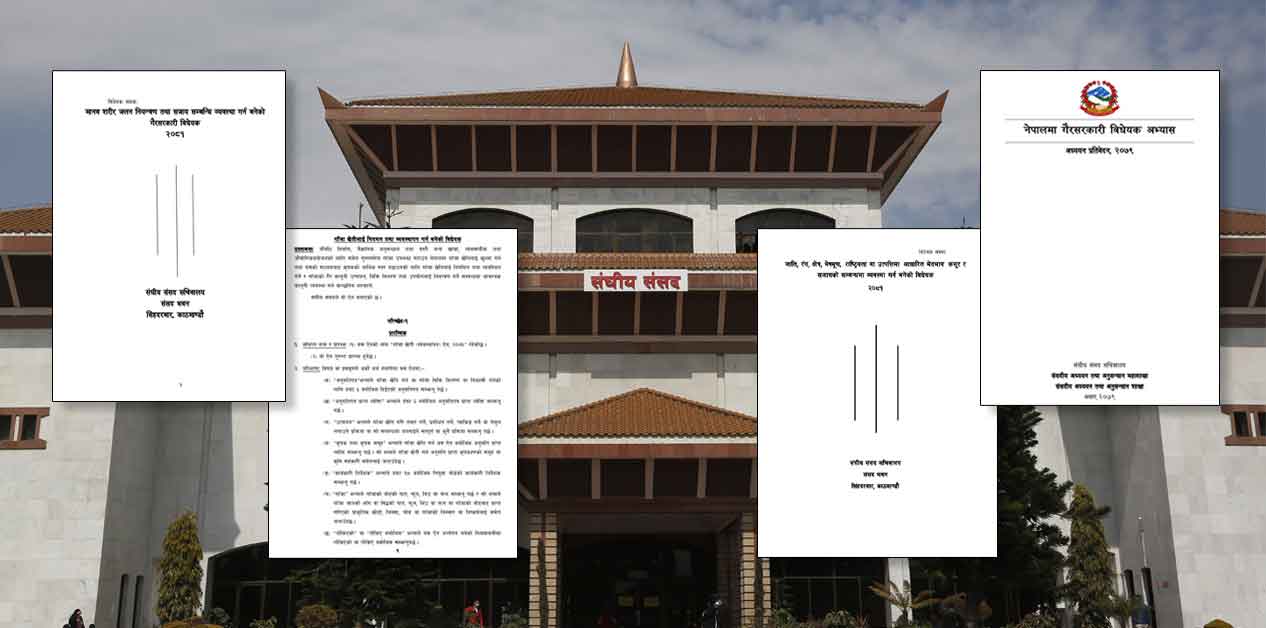

House of Representatives meeting hall. Photo: Bikram Rai/Nepal News

Accordingly, MPs can introduce non-governmental bills on any issue except finance and security. The ‘House of Representatives Rules of Procedure, 2022’, also allows MPs to register private bills.

Registering a bill is not something to be done without study or merely on a whim. When the government hesitates to address matters of public importance, it is natural for MPs to take initiative by registering private bills. This not only highlights their individual roles but also draws Parliament’s attention to public issues. Yet, most private bills in Nepal end up being neglected by the government.

Former MP Hridayesh Tripathi says: “The more developed the parliamentary system, the more priority private bills get in the legislature. In Nepal, it’s the opposite—the government is more active in advancing bills drafted by civil servants who passed the Public Service exams.”

Based on his experience, draft bills are usually prepared by representatives with relevant expertise—farmers on agricultural issues, labor leaders on workers’ matters, and education experts on schooling—which makes the content more substantial. “This kind of practice has not yet been adopted in our Parliament,” he notes.

Former MP and parliamentary affairs expert Mahesh Acharya adds, “When the government does not give serious attention to matters of public concern, it is natural for MPs to push forward private bills. But to give them legal form, support from both the government and Parliament is necessary.”

According to the ‘Practice of Private Bills in Nepal’, the country that gives the most private bills legal status worldwide is Canada, which passed 229 private bills from 1910 to 2008.

The country where the most private bills are registered is Israel. From 1999 to 2018, Israel registered 26,393 private bills. During the same period, Italy registered 18,578, Belgium 7,831, Portugal 4,661, and Hungary 2,863.