A nationalist's paradox: Why Yogi gave treasures to a foreign nation?

King Mahendra’s chief personal secretary, Lok Darshan Bajracharya, mentions an event of serious importance in his memoir published in ‘Yogi Narharinath Abhinandan Grantha.’ According to the book, Yogi Narharinath, in order to set up an archive to safely keep the historical and archaeological stone inscriptions, copper plates, palm leaves, golden leaves, gold foil, genealogies, and other rare documents and original proofs he collected, goes to Bajracharya, the then chief personal secretary of the king, to ask for help.

Bajracharya tells Yogi that such a profound and nationally important task is not possible for him alone and advises him to meet the king directly. As a result, he arranges a meeting between Yogi and King Mahendra. For this purpose, Yogi then repeatedly goes to King Mahendra, the Prime Minister, and the Education Minister. Years pass, but nothing happens. Yogi gets disappointed. In the end, he gives the historical documents and proofs he collected to an educational institution in India.

Much later after this incident, during a meeting, Bajracharya directly questions the Yogi, “Why did you donate such invaluable assets, which you painstakingly gathered, to a foreign institution instead of keeping them in your own country? It seems very uncommon for a nationalist person like you to do so.”

Yogi, in an irritated response to Bajracharya’s question, says, “Why are you accusing me like this? In this nation, a nationalist has no value. Nor is there any value for the collection, preservation, or nationality of national assets. Do you know? I repeatedly requested a national archive and library from a person like your king, who is a national hero, expressing everything in my heart, and after much difficulty, I received a positive assurance, but it could not be implemented. When I went to the then prime minister and the education minister for help, nothing was done to implement my nationalist sentiment and good intentions. After shouting and running around, I got tired and disappointed. Now, since my value is not appreciated in my own country and since no one has the intention of supporting such selfless work for the nation’s welfare, I handed over all the materials I had collected to an Indian educational institution. I did this with the hope that even if my countrymen did not appreciate it, it might receive appreciation abroad.”

Yogi Narharinath. Photo: Madan Puraskar Library

Even though he gave the historical documents and proofs he had collected to a foreign institution out of anger and disappointment, it is evident that the need for a reliable institutional arrangement within the country to safely keep such national assets and documents bothered Yogi even later. The proof of this is found in the introduction to the second edition of his work, Sandhipatra Sangraha (Part–1), published in 1998. In that introduction, Yogi writes, ‘It is desirable that everyone have an interest in such historical publications, and for this, an active and reliable institution is also needed.’

However, the irony is that many years ago, Yogi had already given an unknown number and quantity of such historical and archaeological proofs to an institution in India.

The size and importance of the research

There is no disagreement that Yogi Narharinath did a great service to the country and Nepali society by tirelessly travelling to every nook and cranny and collecting original copies of papers, stone inscriptions, palm leaves, golden leaves, treaty letters, golden plate letters, genealogies, eulogies, and literary and religious texts and their manuscripts. In praise of Yogi’s work, historian Dinesh Raj Pant writes in the same felicitation volume, ‘Researchers like Baburam Acharya and Nayaraj Pant were mainly engaged in research in and around the Kathmandu Valley, while Yogi Narharinath extended his research area throughout Nepal and even outside Nepal, greatly increasing the collection and publication of historical materials.’

According to Pant, Prithvi Narayan Shah’s Divyopadesh was first published by Yogi. Similarly, he credits Yogi Narharinath with publishing Gopalrajvanshavali to shed light on the history of Nepal’s medieval period and for discovering an inscription from the Lichhavi period in Gorkha, which established the fact that ancient Nepal extended beyond the valley.

No one has a definitive answer to the question of how many and what kind of historical proofs and documents Yogi collected. One reason for this is Yogi’s ascetic style of searching for and storing materials. That is, the disorganized and haphazard manner. Because of this, it is difficult to find solid details about the materials Yogi collected, edited, and wrote.

According to Swami Prapannacharya, the biographer of Yogi Narharinath, Gorakshagranthamala Publication has published 114 of Yogi’s works, including collected, edited, and translated ones. This includes seven parts of the Sandhipatra Sangraha. But what is interesting is that the first part of the Sandhipatra Sangraha itself contains 1100 records and more than 200 historical photos, maps, and illustrations in its 800 pages. According to historian Kashinath Tamot, the Sandhipatra Sangraha (Part–1) contains, in addition to records, 20 texts, including Meghdoot and 15 genealogies.

Researchers have concluded that Narharinath’s collection, in addition to Sandhipatra, Dharmapatra, and inscriptions, also contained many historical materials reflecting the past of the Nepali language and culture. Janak Lal Sharma revealed in his article that Yogi Narharinath broke his vow of silence for a few days when he found the original copy of the poem titled Prithvi Narayan by Suwanand Das, which is considered ‘the first poem written in the Nepali language.’ In the same article published in Yogi’s felicitation volume, he says, “On this journey, we received more than 500 ‘Syahamohar and Lalmohar.’ We did not even count the stone inscriptions, wood inscriptions, copper plates, gold plates, and bell inscriptions. Various genealogies also came into our collection. A large amount of historical material was collected.”

Rajendra Dahal. Photo: Bikram Rai/Nepal News

Another researcher, Nayanath Paudel, has written that Yogi’s collection also included a Kanakpatra (golden plate letter) from 1356, from the time of the Karnali region’s King Prithvi Malla Dev, which shows an ancient example of Nepali writing. According to Paudel, that Kanakpatra has greatly helped linguists to understand the origin and development of the Nepali language.

Some of Yogi’s followers who have published books in recent times have mentioned the number of Yogi’s works as 572. But, regardless of the exact number, there is no disagreement that the historical and evidentiary importance of the original papers and objects that Yogi collected by traveling to every village in Nepal is extremely high.

The value of original evidence or original sources in archaeological studies and history writing is expressed in a short article by scholar Naya Raj Pant published in the same felicitation volume. In it, Naya Raj Pant writes, “In the monsoon of 1954, I went to Changunarayan under the leadership of Yogi. This day’s journey was very successful. This journey decided that the number of the Lichhavi period, which had been a subject of debate as to whether it was three or nine for a long time, was seven.”

Because the Lichhavi-era inscription remained in its original form in the premises of the Changunarayan temple, history researchers were able to remove the confusion about the Lichhavi-era number and enrich their own and society’s knowledge base. This further clarifies the importance of the original form of historical documents. Photos or copies can never replace original documents. That is why papers, genealogies, and other documents of historical and archaeological importance, as well as stone inscriptions, Syahapatra, and sculptures, are conserved and protected with high importance.

Question–1

From the public writings of Lok Darshan Bajracharya, the chief secretary to the king, we know that Yogi Narharinath understood the importance of the historical proofs and documents he collected by traveling on foot throughout the country and even in some foreign lands with the help of other scholars and researchers. He went to the door of the then King Mahendra to ask for help for the safety, protection, and proper use of those materials. At the same time, it is clear from more than one article published in Yogi’s felicitation volume that King Mahendra repeatedly helped and used Yogi for political and other work; Yogi was used, and in some instances, Yogi also ‘used’ King Mahendra.

Looking at the close relationship that developed between King Mahendra and Yogi Narharinath, especially around 1957/58, and the context of the time, it seems that King Mahendra should have gladly accepted Yogi’s proposal to build an archive and implemented it immediately. But why did Mahendra ignore the opportunity to help protect the historical objects that Yogi had collected on his own and take credit for it himself?

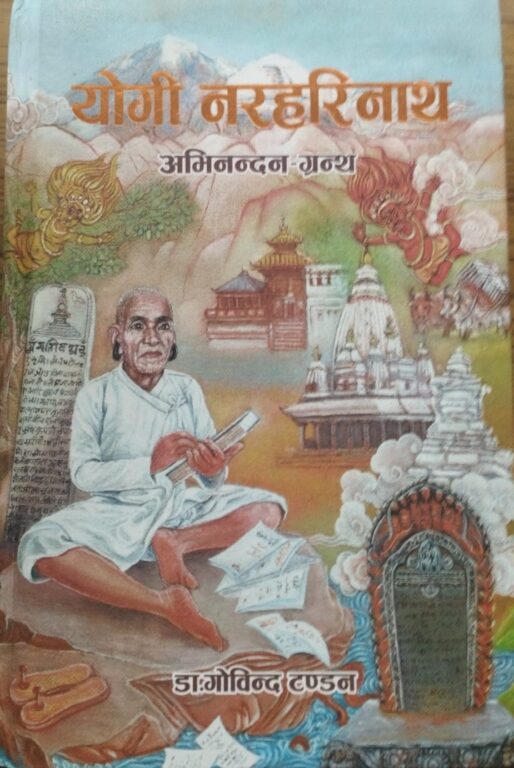

Cover of Yogi Narharinath’s ‘Abhinandan’

If he wanted to, he could have built another building like the Pragya Pratisthan or provided government buildings from existing libraries and offices, among other things. Whether he built a new one or gave an existing building, it would have been done with the state’s property; the king’s private property would not have been affected. On the contrary, his ‘nationalist’ image could have been further brightened as a ‘king who made a significant contribution to the protection’ of valuable documents and proofs that tell the past of the Nepali nation and society.

But, for some reason, the given account shows that a king with a ‘nationalist’ image, who could have made a great contribution to Nepali nationality, turned away from this important work. Reading Chief Personal Secretary Bajracharya’s account, one gets the impression that King Mahendra not only ignored but even spurned Yogi on this matter. Yogi himself admits, ‘After shouting and running around, I got tired and disappointed.’

Question–2

Narharinath embarked on his study and research of Nepal’s historical, archaeological, social, and religious aspects out of his own interest and self-motivation. His devotion to Nepali nationality and Sanatan Dharma-culture was immense. His influence was unique not only within Nepal but also in India. Of the approximately 70 Kotihom (a Sanskrit word meaning sacrificial offering) he conducted, 14 were completed in New Delhi and other cities in India. Along with the Kotihom, dozens of Sanskrit schools established by Yogi are still well-operated in villages and towns in Nepal today.

Two icons of ‘nationalism’

Today’s Nepal Sanskrit University is built on the foundation of the Sanskrit University he tried to establish in Dang. He could unite the country’s famous scholars and experts in historical and archaeological research and study. In other words, whatever Yogi Narharinath was, he was self-made; he was self-motivated. It appears that he received ample support from the common people and scholars for his good deeds, but there was no direct contribution from the government and kings.

Nevertheless, just because King Mahendra and his government did not care to safely keep the national assets collected by him, why did a nationalist like Yogi hand over his collection to a foreign institution? Even though he collected them, those proofs and documents were in fact the common property of the Nepali people, the assets of the Nepali nation. Before donating such invaluable items to an unknown institution abroad, how did Yogi forget his duty to the nation?

Nationalist identity

A major basis for the above questions targeting King Mahendra and Yogi Narharinath is their so-called ‘nationalist’ image prevalent in the Nepali public. That is, King Mahendra and Yogi Narharinath are still synonyms of ‘nationalism’ for many people.

Many of their followers are still found doing politics under the umbrella of this ‘nationalist image.’ But the above incident and related account, made public by King Mahendra’s chief personal secretary, force one to question that nationalist image of both of them.

– Dahal is the editor of Shikshak Monthly Magazine.