KATHMANDU: In 1977, I was working as a journalist for the Rastriya Samachar Samiti, Nepal’s national news agency. I had a habit of asking difficult questions, and in diplomatic circles, very few people didn’t know me. There was an Indian embassy official named Menon who used to say, “Chris! You must bring your wife to my parties. You can’t come alone.” Foreigners fondly called me Chris.

At the time, it was customary for foreign ambassadors stationed in Nepal to travel across the country once a year. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs would often include local journalists in these tours, and my name was frequently on the list. I had the opportunity to accompany delegations hosting ambassadors from countries like China, East Germany, and Hungary.

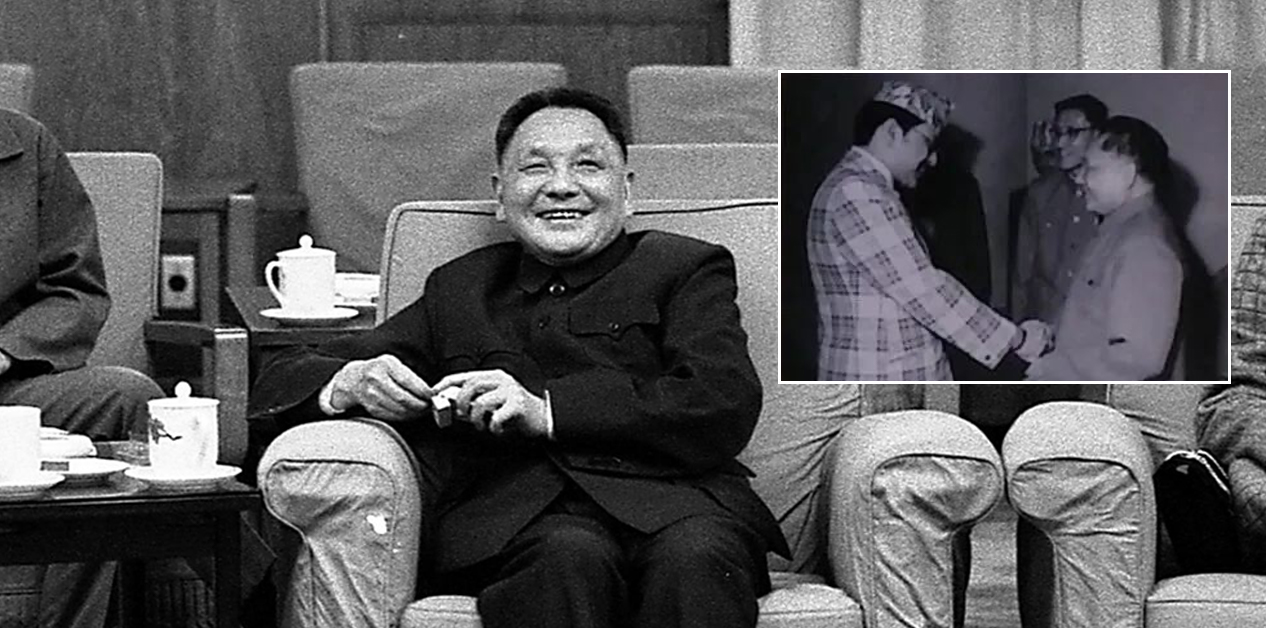

But that particular year brought something unforgettable — a rare press conference with none other than Deng Xiaoping, the architect of modern China.

Mao Zedong, the founding leader of the Chinese Communist Party, had passed away on September 9, 1976. Following his death, Deng, who had previously faced political downfall and persecution at the hands of the “Gang of Four” during Mao’s reign, began to re-emerge. The world watched with intense curiosity as Deng began steering China toward modernization.

On February 3, 1978, Deng Xiaoping arrived in Nepal for a state visit — his first international trip after taking charge of China’s leadership 17 months earlier. This made it a high-profile event, drawing significant global media attention.

By Chinese diplomatic tradition, Myanmar (then Burma) is typically the first foreign destination visited by Chinese leaders — a tradition rooted in historical ties, as Burma was the first country to sign a border agreement with Communist China. Deng honored this custom and visited Myanmar before flying to Nepal.

He arrived in Kathmandu aboard a Chinese Trident aircraft, carrying a 19-member delegation. At the time, Deng held the post of Deputy Prime Minister. Following Mao’s death, Hua Guofeng had succeeded Zhou Enlai as Prime Minister, and also taken over as Chairman of the Communist Party.

This was the first international trip by a Chinese leader after the deaths of Zhou and Mao, making Nepal the center of international diplomatic attention.

Two years earlier, King Birendra had made history by flying over the Himalayas to visit Tibet — the first foreign head of state to use the “Trans-Himalaya” route. Now, Deng Xiaoping had chosen the same route to come to Kathmandu. Before his arrival, two Chinese jets had flown from Lhasa to Kathmandu on January 16 to survey the difficult air corridor.

At the time, Deng held the post of Deputy Prime Minister. Following Mao’s death, Hua Guofeng had succeeded Zhou Enlai as Prime Minister, and also taken over as Chairman of the Communist Party.

Captivated by Nepal’s Himalayan landscape, Deng reportedly left his seat during the flight and went to the cockpit to admire the mountains. This detail was even reported in the press.

Deng’s delegation included Deputy Foreign Minister Han Nianlong, Ambassador Peng Quanwei, and Shen Ping, Director of the Asian Division at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Around 30 international journalists had flown into Kathmandu a day earlier to cover the four-day visit.

Nepal’s then Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista gave Deng a grand reception. On the first day, high-level talks between Nepali and Chinese officials were held inside Singha Durbar.

At the time, the RSS (Rastriya Samachar Samiti) office was also located inside the Durbar complex. While foreign journalists, including those from India, were allowed into the press area, no Nepali journalists were invited.

Bhola Regmi, who was in charge of the economic beat at RSS, was working with me. I turned to him and said, “Okay, Regmiji, let’s scale the wall.”

I was brimming with excitement. For me, even getting a story from the lion’s mouth wasn’t out of the question. He was hesitant, but I reassured him: “Don’t worry. Nothing will happen.”

And so, we climbed over the compound wall and entered the negotiation hall. The official talks had just concluded and a joint press conference was underway. I asked for two chairs, but my mind was fixed on one thing — to get close to Deng Xiaoping and secure a brief one-on-one moment with him.

As the press conference ended and Deng began to exit the hall with Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista. I moved in swiftly, and approached him.

Nepal’s then Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista gave Deng a grand reception. On the first day, high-level talks between Nepali and Chinese officials were held inside Singha Durbar.

Just as I was about to ask my question, the Chief of Protocol stepped in and cut me off: “Tomorrow,” he said. I was stunned.

Deng had been smiling. He looked right at me — ready to engage. Even Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista had nodded encouragingly, saying “Yes… yes,” to set the tone. But with that one word — tomorrow — the moment slipped away. Still, I wasn’t going to let it go.

At exactly 3 p.m. on February 4, I arrived at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a few of my journalist friends. We were fully prepared. The venue was packed — Nepali style, as we used to call it. But there was no sign of a press conference starting. After a long wait, we stepped out for tea.

And just as I returned, climbing the steps with a warm cup in hand, I heard the commotion — the press conference was already underway. I nearly dropped the cup. The tea had nearly drowned my chance at a headline.

Inside the hall were many top-tier foreign journalists — BBC’s Mark Tully, correspondents from AP, The Times of India, and several others. At the head table sat Prime Minister Kirtibabu (Kirtinighi Bista), Deng Xiaoping, Devendra Raj Pandey, and other senior officials from both countries.

When the floor opened for questions, I didn’t hesitate. I stood up and asked Deng, “Deputy Prime Minister, when are you opening Tibet for people to travel?”

Deng smiled. “Oh… Tibet is a very difficult mountainous region, you know. It’s at high altitude,” he said. “I myself want to go to Tibet. But my doctor has advised me not to go right now.”

The interpreter translated his answer into Chinese. I quickly followed up.

Xiao participated in a civic felicitation during his visit to Nepal

“I’m talking about others — people like you. Tourists are physically and mentally eager to go to Tibet. They want to experience the beauty of the region.”

This time, Deng looked slightly puzzled. “I think they’re still busy with reconstruction work,” he said. “We will open it… as soon as possible.”

I pressed on. “What do you mean by ‘quickly,’ Deputy Prime Minister?”

This time, his reply was firm and to the point: “Two to three years.”

That single sentence exploded across the global press. Within hours, media outlets were flashing headlines: “China to Open Tibet in Two to Three Years” — it became banner news around the world.

But I wasn’t done yet. I turned the conversation to a more sensitive issue — the Gang of Four.

“Deputy Prime Minister,” I asked, “the world is still very curious — what is the current status of the Gang of Four? Do you have anything to say?”

I genuinely didn’t expect him to answer. It was a controversial topic. But Deng surprised everyone.

“They’re working on infrastructure construction,” he replied. “It will probably take two to three years.”

The journalists in the room barely waited for the translation to finish before rushing to file their stories. Once again, a scoop. But perhaps the most satisfying moment came months later.

Seven or eight months after Deng’s visit, I was in the United States on an IVP (International Visitor Program) fellowship. One day, I visited the office of a local newspaper outside New York City. I introduced myself as a journalist from Nepal. The editor seemed intrigued. She pulled out an old issue of their paper and said, “Look, we also covered news from Kathmandu.”

To my amazement, there it was — a story quoting Deng Xiaoping’s answer to the very question I had asked him.

I turned to the editor and asked, “Do you know who asked that question to the Chinese Vice Premier?” She shook her head. “No.”

I smiled and said, “That journalist is me.” She looked at me in surprise, her curiosity visibly piqued. For a moment, she just stared — as if trying to reconcile the person in front of her with the dateline from halfway across the world.

(Based on a conversation between Nabin Aryal and Krishna Prasad Sigdyal)