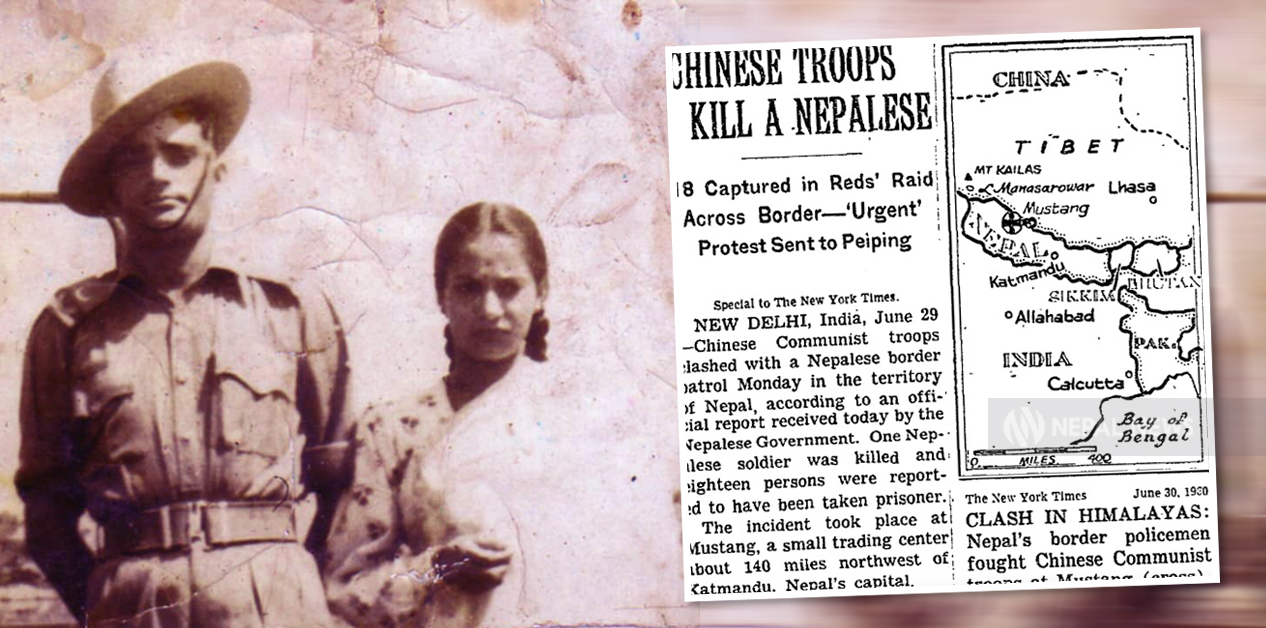

KATHMANDU: Warrant Officer (Subedar) Bam Prasad Baskota was the first Nepali Army soldier to be killed in the Khampa conflict.

On June 30, 1959, he was shot dead by the Chinese army near the Nepal-China border in Mustang. At the time, the incident had the potential to spark international outrage. But both the Nepali and Chinese governments chose to keep it under wraps.

Born in Thamle village of Okhaldhunga in eastern Nepal, Bam Prasad came from a modest, working-class family. He joined the Nepali Army in 1948 and steadily rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a Warrant Officer. By the time of his death, he had completed officer cadet training and was under consideration for another promotion.

At the time of the incident, he was serving in the Mahendra Battalion in Pokhara. One day, an urgent order arrived: The Khampas are wreaking havoc in Mustang—you must move out immediately.

He left for Mustang with 16 soldiers, assuring his wife before his departure: “I’ll return as soon as the operation ends.”

Based on intelligence reports that Khampa rebels had raided Jomsom—looting grain, livestock, and horses—the unit began a search operation across the Nilgiri Himalayas, near the Nepal-China border. It took 14 days to reach Mustang on foot, navigating the rugged terrain of the region.

During an inspection of a local villager’s home—accompanied by a government official—they confirmed the extent of the Khampa raids. But before they could act further, the Chinese army, having crossed into Nepali territory, opened fire without warning.

This act was a clear violation of international law, as the Chinese military had unlawfully entered Nepal’s border. Bam Prasad was killed on the spot. Another soldier was wounded. All remaining members of the unit were taken hostage by the Chinese.

The chaos unfolded despite the pleas of a local interpreter—himself shot in the knee—who tried to explain that they were Nepali soldiers, not Khampas. According to witness statements, the Chinese army fired indiscriminately, without attempting to verify identities.

Bam Prasad’s education had earned him respect in the army. In fact, his commander at the Mahendra Battalion, Guna Shumsher Rana, had offered him an exemption from the operation. But Bam Prasad declined. He chose to lead from the front.

The incident occurred on the 15th day of the operation. That morning, far away from the front lines, Nila Devi had seen a terrible dream. When the constable’s wife came into her room and began breaking her bangles—a cultural symbol of widowhood—she still had no idea what had happened. Then she noticed members of the battalion quietly gathering outside her room. “Guna Shumsher finally told me,” she says. “I fainted on the spot.”

Now in her old age, Nila Devi lives with her daughter in Inaruwa, Sunsari. But the pain of that day, nearly 66 years ago, remains vivid.

“The night he died, I felt it,” she says. “I knew something was terribly wrong.”

Bam Prasad’s education had earned him respect in the army. In fact, his commander at the Mahendra Battalion, Guna Shumsher Rana, had offered him an exemption from the operation. But Bam Prasad declined.

After her husband’s death, Nila Devi attempted suicide several times. While returning to Kathmandu after completing the 13th-day mourning rituals, she tried to jump from an airplane. She had even wrapped a stone in her saree, intending to use it to break the plane’s window.

“Once I boarded the plane, I realized it wasn’t possible to break the glass,” she recalls. “After landing at Kathmandu Airport, I threw the stones away. I also jumped into the Seti River and walked with the intention of dying. But my body was weak, and I fainted along the way.”

In Kathmandu, she stayed with a woman from her village who worked as a cook in Rana’s house. Many people offered her words of comfort and advice, but none truly understood her pain. Clad in a torn white saree, she went to the Prime Minister’s Quarters in Tripureshwor to meet Prime Minister B.P. Koirala.

Recalling the moment, she says, “BP comforted me, saying, ‘It didn’t just happen to you, dear. The country has lost a promising son. He was not only your husband, but a son of the nation. Don’t grieve too much. The government will properly honor his martyrdom.’”

BP also asked her, “How old are you? What does your father do? Has he remarried?” When she replied that her father had remarried, BP said, “You’re grieving, child. I will help you.”

Opposition leader Bharat Shumsher also raised his voice in Parliament, demanding justice for Bam Prasad’s family.

At the time, it was publicly announced that the Chinese government had donated 50,000 rupees to the family of the deceased. However, Nila Devi never received that money. While living in Pokhara, she knew BP’s security guard, Captain Nagendra Bahadur, who intervened on her behalf. As a result, BP arranged for her to receive 15,000 rupees.

BP also asked her, “How old are you? What does your father do? Has he remarried?” When she replied that her father had remarried, BP said, “You’re grieving, child. I will help you.”

Unfortunately, she was unable to manage the money properly. The then Chief of the Royal Nepal Army, Neer Shumsher Rana, had handed the sum to industrialist Kamal Rana, instructing him to invest it and provide returns. But Kamal Rana deceived her, and she was eventually forced to return to her parental home.

Years later, when Surendra Bahadur Shah became Army Chief in 1965, she returned to Kathmandu seeking justice, holding her 4-year-old daughter in her arms. She went to the Army Headquarters in Bhadrakali and poured out her grief to Shah. Moved by her story, Shah gave her 800 rupees from his own pocket.

“Later, it was because of him that Kamal Rana returned the money,” she says. Nila Devi had also sought help from King Mahendra, but her case continued to be passed from the Army to the Ministry of Defense, and then to the Ministry of Finance, without resolution.

“When Girija Prasad Koirala became Prime Minister in 1994, my mother finally received 50,000 rupees,” says her daughter, Geeta. “That amount was provided as a gratuity after the old case was reviewed. This year, she also began receiving a pension—but only after a long legal battle.”

Geeta was born in March 1961 in Nila Devi’s native village of Okhaldhunga. Her maternal family took full responsibility for her upbringing and education. Now 63, Geeta is married and works in the teaching profession. She lives with her 84-year-old mother under the same roof.

(Kunwar is the author of ‘Nepali Dristikon Maa Khampa Bidroha’ (Khampa Rebellion from a Nepali Perspective)