The Gen Z protest on September 8 is still etched in my mind as a tragic scene in front of the Federal Parliament building. The demonstration, organized by young people demanding an end to corruption and good governance amid rising dissatisfaction after the government blocked social media, began peacefully.

However, as the crowd moved from Maiti Ghar Mandal to New Baneshwor, the streets quickly turned into a battlefield. Police opened fire on the protesters. Within a few hours, 19 lives were lost, and many were injured.

The next day, the movement grew even more violent, displaying a destructive frenzy. Parliament was burning before my eyes. Soon after, Singha Durbar, the Supreme Court, other government offices, and private homes were also engulfed in flames. Amid piles of ash and choking smoke, I could not maintain my composure to report.

Even though I stepped back from that chaotic scene, the duty of journalism would not let me stay silent. I went to the hospital, where the cries of Gen Z protesters wounded by bullets were calling out. Why did they risk their lives and take to the streets? Answering this question was part of my professional responsibility—but this journey became more human than informational.

On the sixth floor of the Trauma Center, in bed no. 502, 25-year-old Pawan Shahi of Lalitpur City FC, NSL champions, was lying wounded. He was the subject of my story, but seeing his critical condition, I had to hide my identity. Through a brief conversation with a person standing nearby, I learned that he had been shot during the protest.

After three days on a ventilator, he regained consciousness. His face bore the lines carved by the struggle between life and death. The duty of a journalist is to inform, but in such a disaster, how just is it to stir the wounds of the suffering family with questions? This internal conflict left me unsettled.

The ward was crowded with Pawan’s grief-stricken parents and relatives. I mingled in the crowd but could not reveal my journalist identity. When the hospital security guard asked the crowd to disperse, I stepped outside with them. Summoning the courage to speak with a grieving mother was extremely difficult.

After half an hour outside, I finally introduced myself to Pawan’s mother, Mithu, and gathered the courage to speak. After repeated requests and a two-hour wait, she agreed to talk.

She narrated the harrowing emotions of the day her son was shot—the moment when doctors could not determine if he was alive or dead, and when her brother Ganesh Shahi felt his chest to check if he was breathing. Hearing this, my heart trembled.

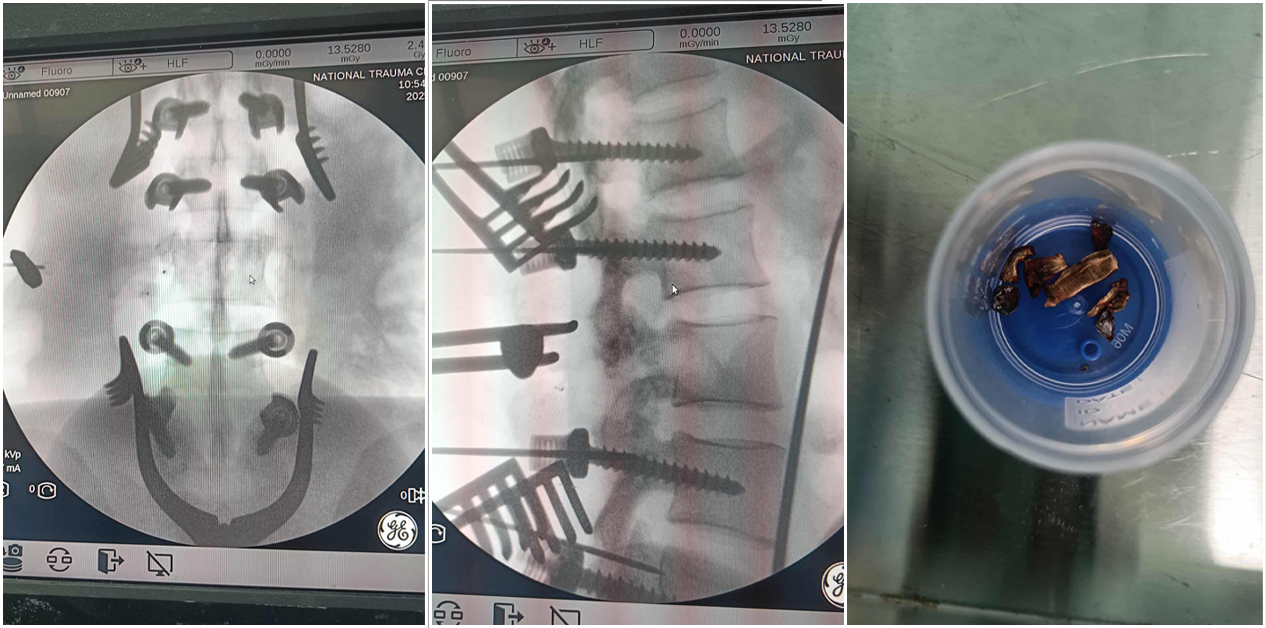

Following six hours of surgery, Pawan’s perforated intestine and bullet-punctured colon were treated. Doctors treating the injured protesters were themselves mentally affected by the complex conditions, bullets removed during surgery, wounds, and the statements of the injured. This was shared by Badri Rijal, head of the Trauma Center.

He admitted that witnessing all these scenes also left him traumatized. Hearing him speak, I too felt chills.

Though Pawan regained consciousness, he is not yet able to speak. Therefore, I could not get answers about how he became involved in the protest or why he was ready to take bullets. Leaving those questions unresolved, I stepped out of the Trauma Center.

Pawan’s story left me shaken. However, I went to meet another injured protester, 25-year-old Prasanna Kafle, at Civil Service Hospital in Min Bhawan.

Prasanna from Kavrepalanchok lay in bed with a bullet wound in his left leg. He had crawled to the hospital after being shot near the Parliament gate around 1 PM on the day of the protest.

He had joined the streets following a call on TikTok. Expecting the demonstration would remain nonviolent, he watched his own blood dry on the hospital bed, seeking answers to how the protest escalated.

Most of the Gen Z injured lying in hospital beds shared similar stories. Some were students who came from villages with hopes of a better future; others were seeking employment to support their families. Their families were not present to care for them; only friends offered support. Some had nothing but a single blood-stained cloth.

Food, snacks, and clothes provided by some organizations were not sufficient relief for the injured. After discharge, the lack of provisions and rations in their rooms caused further distress. The bullets fired by the government during the protest left not only physical wounds but also deep mental scars. Their stories still leave me restless.

The experience of reporting this post-protest tragedy has taught me a lesson: journalism is not only about conveying information, but also a bridge of humanity. In reporting such disasters, human sensitivity must be prioritized, or the journalist’s own mind becomes unsettled.