629740 sq. feet of land, purchased over the legal limit for industrial operation, was illegally sold to another group 25 years ago via Cabinet approval

KAVRE: Nestled at the base of a dense green forest, Bhandari village, situated in Ward 9 of Panauti Municipality (then part of the Khopasi Village Development Committee), experienced a profound shift following the political change of 1990. Word quickly spread that a major cement industry was slated for the area.

Subsequently, representatives from the powerful industrial conglomerate, the Chachan Group, began making strategic visits. Their objective was to acquire land for two distinct operations: a limestone mine in Ward 11 of Panauti Municipality (then part of the Balthali VDC) and a large-scale cement factory to be established right in Khopasi.

According to the Mayor of Panauti Municipality, Ram Sharan Bhandari, when representatives of that group, which was doing business in Birgunj, arrived saying they would open Trishakti Cement Industry, the residents of Khopasi-Balthali were excited. Hoping for employment and development, the villagers started selling their fields and farmlands.

The law grants land ownership based on the nature and purpose of the industrial company. In the case of cement industries, medium-level industries can purchase 300 ropani (1642800 square feet) of land, and large industries can purchase 500 ropani (2738000 square feet) of land in all hilly areas except the Kathmandu Valley. If a company needs to purchase more land than that, the concerned company submits an application to the Department of Land Management and Archive, and a decision from the Council of Ministers, based on the recommendation of the Ministry of Land Reform, is required. From 1990 to 1993, the Chachan Group purchased 214 ropani (1171864 square feet) of land in Kavre.

After buying the land, however, the Chachan Group never returned. For seven or eight years, there was neither a factory nor employment. Instead, the Trishakti Group opened the Trishakti Cement Factory in Parsa in the fiscal year 2003/04. Meanwhile, the land in Khopasi and Balthali remained barren.

The land in Khopasi, which was bought to open the Trishakti Cement Industry, is now being developed into a residential area. CG Holdings, a part of the industrial house Chaudhary Group, is building ‘housing’ here. Mayor Bhandari says, “Bungalows have been erected in the very place where they were once shown the dream of opening a cement industry.”

CG’s housing project is being built after the Trishakti Cement sold the land, which was freed from the land ceiling through a decision by the Council of Ministers. This construction work has been continuous for four years. According to the Eighth Amendment to the Land Act, 1971, a company that receives an exemption from the land ceiling is not allowed to free it up and sell the land to an individual, nor is an individual allowed to purchase such land. Documents show that such land was bought and sold between Trishakti and industrialist Binod Chaudhary in Khopasi.

The mystery that Trishakti Cement Industry had transferred 115 ropani, 10 aana, and two paisa (633333.62 square feet in total) of land above the ceiling limit to industrialist Binod Chaudhary’s name personally back in the fiscal year 2000/01 has been exposed 25 years later. When a case was filed against former Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal and others in the Patanjali Yog Peeth land sale case in Banepa, an application was filed claiming that Trishakti Cement had sold the land ceiling-exempted land to an individual, similar to the Patanjali case, and the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) is now studying the file.

CG Holdings’ new housing project in Khopasi, Panauti, built on the disputed land formerly held by Trishakti Cement. Photo: Khila Nath Dhakal/Nepal News

“CG Homes” is currently under construction on that same land, which is in Chaudhary’s name, through CG Holdings. Rohit Thakur, an employee of CG Homes, says, “It was previously Trishakti Cement’s land, and after it came to our company, work on the residential area started in 2021. Homes are being booked, and there are plans to hand over 18 homes next February.”

The development is rapidly advancing, with preparations currently underway for the launch of the second sales phase, featuring 13 new houses. Concurrently, 75 additional homes are under active construction as part of a comprehensive plan to ultimately deliver 220 residential units on the expansive site. Thakur provided specific details on the plot sizes, indicating a diverse offering to potential buyers. The constructed houses occupy plots ranging from four aana (1369 square feet) and one paisa (85.56 square feet) up to 12 aana (4,107 square feet). Specifically, these plot sizes include four aana and one paisa (1,454.56 square feet), 7.2 aana (2,464.20 square feet), eight aana (2,738 square feet), 11 aana (3,764.75 square feet), and 12 aana (4,107 square feet). Crucially, he noted the starting price point for this exclusive development: a house built on the smallest plot, four aana and one paisa (totaling 1,454.56 square feet), is priced at Rs 20.4 million.

Koirala Cabinet cleared the land

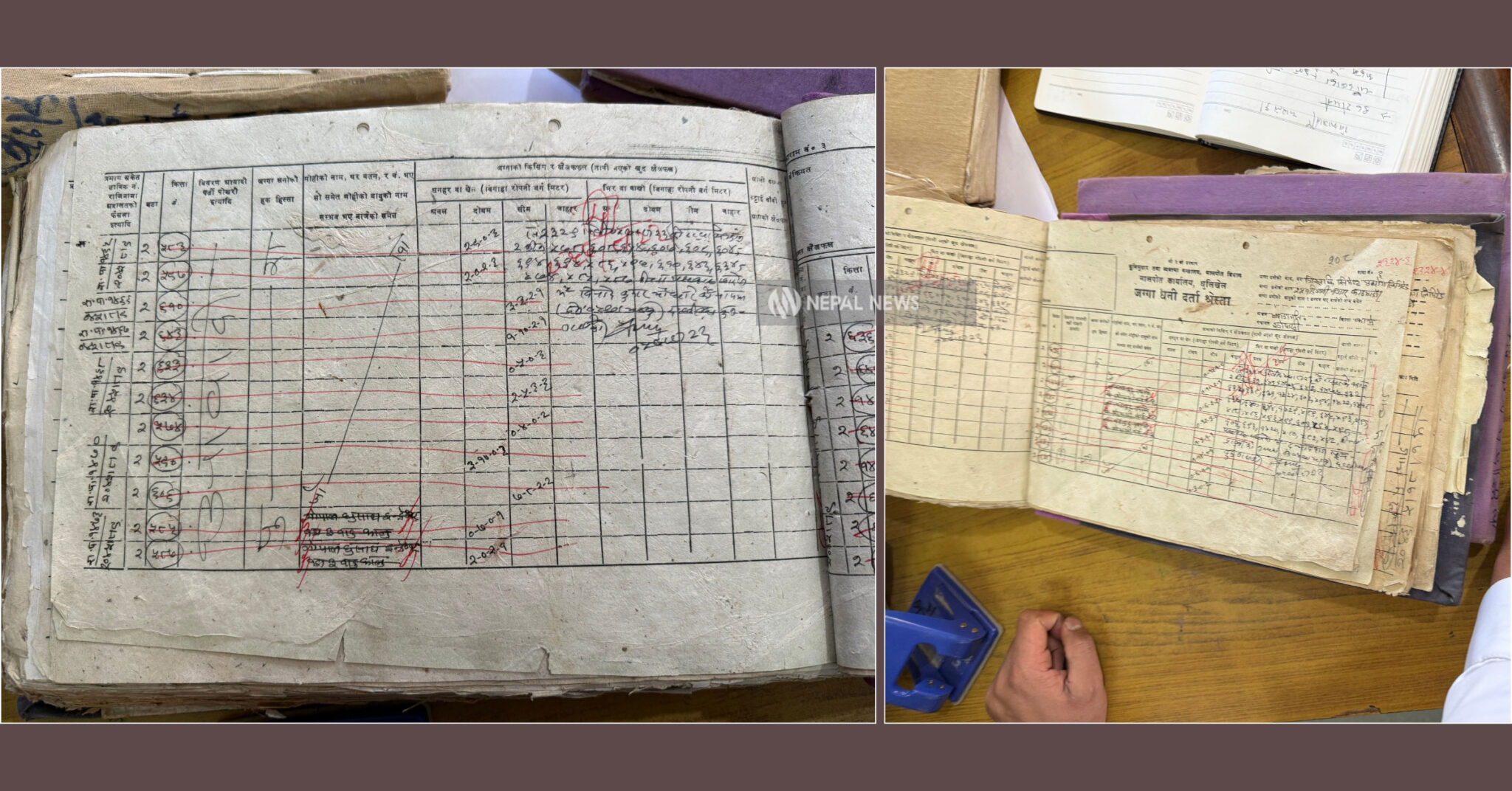

According to the records of the Land Revenue Office, Kavre, and the Survey Office, the decision to free up and sell Trishakti’s land that exceeded the ceiling limit was made by the Council of Ministers under the then Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala, and Chiranjibi Wagle was the Minister of Land Reform at that time. The government’s entry into Trishakti Cement’s land and the decision by the Council of Ministers was on August 6, 1998.

When the decision was made by the Council of Ministers, it was stated that the money from selling the land would be spent on operating the industry. However, the Council of Ministers changed the decision just seven days later. On August 13, 1998, they removed the operation and decided to allow the company to purchase land in a suitable location for establishing the industry within two years.

A condition of the Council of Ministers’ decision was that the land could only be sold after purchasing land elsewhere within two years of the decision to free up the land. Trishakti, holding the Council of Ministers’ decision file, remained silent for two years without purchasing land elsewhere. The Kavre Land Revenue Office’s record shows that the cleared land was transferred solely to Chaudhary’s name on December 8, 2000.

The Chief of the Kavre Land Revenue Office, Ram Bahadur Shahi, says, “The office record shows that after the Council of Ministers cleared the land, Trishakti sold it to an individual. Currently, that land appears to be broken into 57 plots.”

Document confirming the freeze order: The 536648 sq. feet of Trishakti Cement land was frozen by the Kavre Land Revenue Office on March 6, 2001. Photo: Khila Nath Dhakal/Nepal News

Koirala was also the prime minister at the time of the land transaction. However, Siddha Raj Ojha was the Minister for Land Reform. On the very day the land was transferred to his name, Chaudhary transferred some of the land to his brother Arun and Chandbagh School.

Babulal Chachan, the head of the Chachan Group that cleared up and sold the ceiling-exempted land, claimed that there was no land left in Kavre. “I know Kavre district exists, but I don’t know the place called Khopasi, nor have I been there. I also do not know that the company has land there,” he says. “If there was land and it was sold, some employee might have been involved in the transaction; I don’t know anything.”

Attempts to talk to the Chaudhary Group brothers, Binod and Arun, about this were unsuccessful, as they could not be reached. Varun Chaudhary, Binod’s youngest son, says, “I am unaware of the land in Kavre.”

His nephew, Sachit Chachan, also claimed that Trishakti Cement did not own any land in Kavre. “If our company doesn’t even have land in Kavre, how was it sold? I don’t have any idea about that,” claims Sachit.

Attempt to sell the remaining land

After Khopasi, there is also an attempt to sell the 98 ropani (536648 square feet), 10 aana (3422.50 square feet), and one paisa (85.56 square feet) of land in Balthali. Trishakti had applied for permission to free up and sell the land back in 2057 B.S. Trishakti appears to have gone to the Ministry of Land Reform asking for permission on March 31, 2001.

Siddha Raj Ojha, the then Minister of State for Land Reform in Girija Prasad Koirala’s government, decided to free up the 98 ropani (536648 square feet) of land on the very day the application was filed.

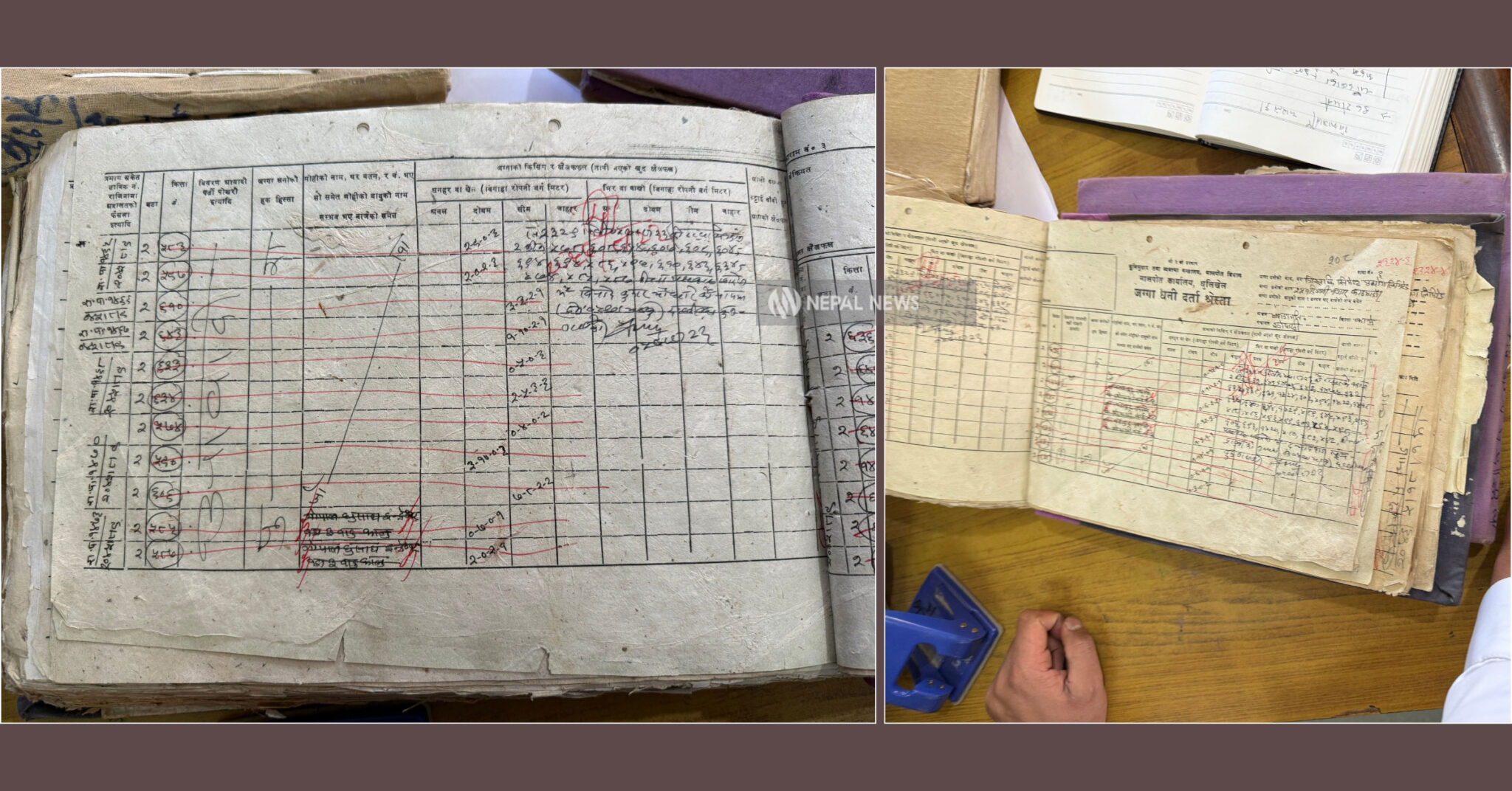

The next day, on March 2, 2001, the Ministry of Land Reform wrote a letter to the Kavre Land Revenue Office to freeze that particular land. Accordingly, the Land Revenue Office froze the land on March 6, 2001.

Document confirming the transfer: Trishakti’s land officially moved to Binod Chaudhary’s personal name on December 8, 2000, as per the Land Revenue Office’s record. Photo: Khila Nath Dhakal/ Nepal News

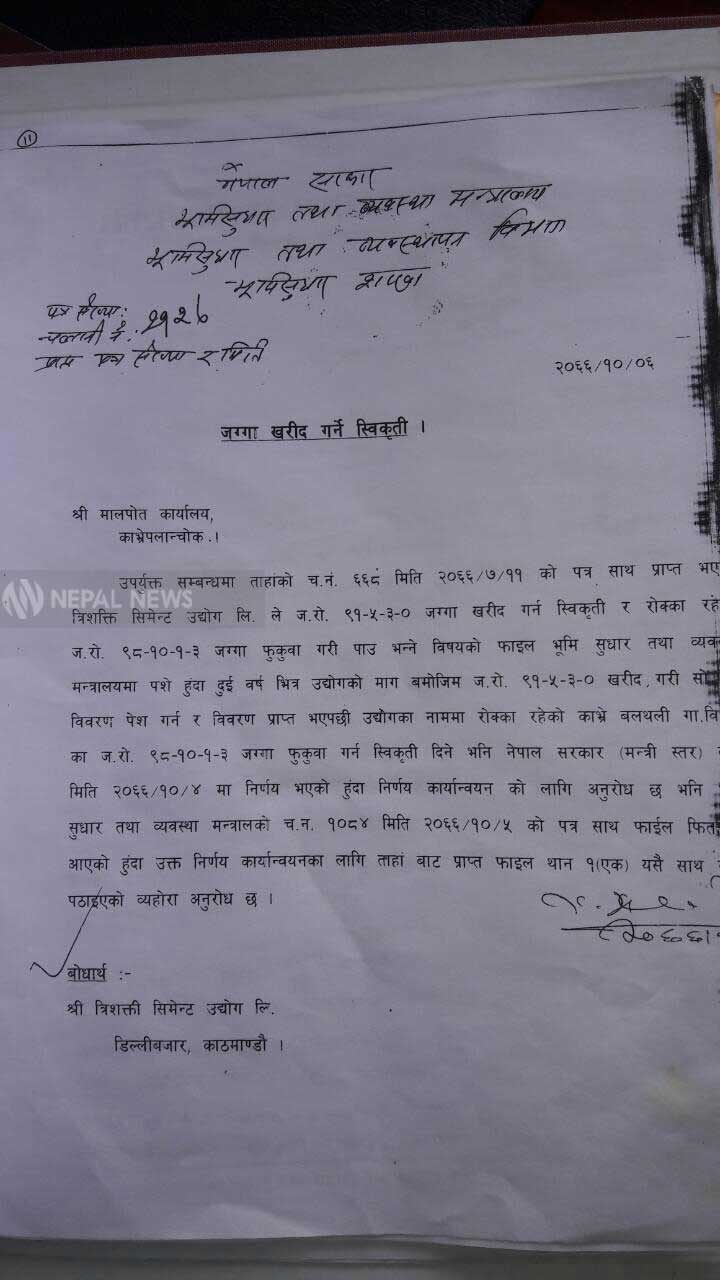

Nine years after the land was frozen, Trishakti Cement went back to the Ministry of Land Reform during the tenure of Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal and the late Land Reform Minister Dambar Shrestha. After arriving at the Land Revenue Office in 2009 and asking for permission to sell the 98 ropani (536648 square feet) of land, a letter was sent from there to the Ministry of Land Reform on October 28, 2009. On January 18, 2010, Shrestha made a ministerial-level decision to allow the land to be freed.

Along with the permission to sell the 98 ropani (536648 square feet) of land, Trishakti also requested permission to purchase 93 ropani, stating they would establish an industry in another suitable location. However, it neither purchased the land nor was Minister Shrestha’s decision implemented. The 98 ropani of land, which has been repeatedly sought to be sold, is currently still frozen in the name of Trishakti. The Kavre Land Revenue Officer, Shahi, states that although a ministerial-level decision was made, the land remains frozen in the Land Revenue Office since the fiscal year 2000/01 because the process was not completed. After this, Trishakti went to the Ministry of Land Reform and Management again in around 2021. “Perhaps because they found out that the land was sold illegally before, the latter decision does not appear to have been implemented,” says Land Revenue Officer Shahi. “In our records, the 98 ropani of land is still frozen; letters for freeing up and selling the land arrived, but no work was done.”

Earlier than Patanjali, yet identical in kind

According to the Eighth Amendment of the Land Act, 1964, enacted in 2020, companies can keep land exceeding the ceiling limit with government approval for limited purposes such as industries. The industries, establishments, companies, projects, educational institutions, or any other organizations that have acquired land exceeding the ceiling limit can only use it for the purpose for which it was acquired. The Act stipulates that such land cannot be sold, transferred in any way, or exchanged by the concerned industry, establishment, company, project, educational institution, or any other organization to anyone.

However, if an industry, establishment, company, or institution is dissolved or goes into liquidation for any reason, it can be sold with the government’s approval under the Act for the purpose of settling the institution’s liabilities. But it can only be sold to an industry, establishment, or company with a similar objective, not to an individual. When Trishakti sold more than 115 ropani (629740 square feet) of land, none of the legal conditions appear to have been fulfilled. Trishakti was also not in a state of being dissolved or going into liquidation.

Another important point is that an individual cannot purchase land that exceeds the land ceiling limit. The law has separate land ceiling provisions for individuals in the Kathmandu Valley, hilly areas outside the Valley, Inner Madhes, and the Terai region. In the Valley, one can keep 25 ropani (136900 square feet) for agricultural purposes and five ropani (27380 square feet) for homestead purposes. In the Inner Madhes and Terai regions, 10 Bighas (729000 square feet) for agricultural purposes and one Bigha (72900 square feet) for homestead. In all hilly areas except the Kathmandu Valley, an individual or their family can keep 70 ropani (383320 square feet) for agricultural purposes and five ropani (27380 square feet) for homestead land. However, transferring Trishakti Cement’s land to an individual appears to directly challenge the provisions regarding the land ceiling.

A copy of the decision by then Land Reform and Management Minister Dambar Shrestha, under the Madhav Kumar Nepal government, allowing Trishakti to free and sell 9,536,648 sq. feet of land. Photo: Nepal News

How did Chaudhary purchase land exceeding the ceiling, and how did the Land Revenue Office approve the transfer? “We sent the file to the CIAA as it was requested, regarding what and how the decision was made at that time,” says Land Revenue Officer Shahi.

Ganesh Prasad Bhatta, spokesperson for the Ministry of Land Reform and Management, says that this cannot happen under normal circumstances. He says, “Normally, this would never happen; it must be done according to the conditions of the Council of Ministers’ decision. If it is not, then legal action is attracted.”

The CIAA filed a case against former Prime Minister Nepal and 93 other individuals, including those involved in the decision, for the illegal purchase and sale of Patanjali Yog Peeth’s land at the Special Court on June 5, 2025. The case, with a claim of Rs 185.8 million per person, is pending in the court.

Patanjali Yog Peeth and Ayurveda Company was registered on January 4, 2008, with the address of Bouddha, Kathmandu. It sought and received government permission to purchase land exceeding the ceiling limit and then sold it. The CIAA filed the case on the basis that Nepal was the prime minister when the policy decision was made before the land was purchased.

Patanjali had purchased the land for herbal farming and the construction of an Ayurvedic hospital. After the ceiling-exempted land was freed, it was sold to the housing company Kasthamandap Business Homes Company.

It has been revealed that the land transaction of Trishakti Cement in Khopasi, Panauti Municipality-9, Kavre, took place before the Patanjali incident. Both transactions, which are similar in nature, involved the Council of Ministers. The only difference is that Patanjali sold it to a housing company, while Trishakti sold it to an individual.

The Land Act has a provision for the government to confiscate such land that is purchased. Since the government can confiscate the land transferred to an individual in the Trishakti case, those who purchase property from CG Homes and those who have currently made a deposit may face problems.

Unsold plot leased out

Trishakti has leased the currently frozen 98 ropani (536648 square feet) of land to another company. However, the Land Act states that ‘land purchased under a ceiling exemption should not be leased or rented to anyone else.’ Trishakti has leased the Balthali land to a mineral company for 20 years. After leasing Trishakti’s land, Kamala Devi Mineral Industry is operating a limestone mine.

Kamala Devi Mineral Industry has been extracting limestone since mid-February 2025. The operators of the industry are Saroj Gautam, Shekhar Mahat, and Min Man Shrestha. Among the operators, Gautam states that the land was leased somewhere around 2018. “The industry was started after a 20-year agreement between Trishakti Cement and us,” says Gautam. “At least 13 years are still remaining on the lease.”

Kamala Devi Mineral Industry’s limestone mine, operating on Trishakti’s land that was illegally leased out. Photo: Khila Nath Dhakal/Nepal News

He states that the mine is operating with permission from the department and that he has no concern with Trishakti’s ceiling-exempted land. “It is a lease agreement; I do not know about other land matters,” he says.

According to Dharma Raj Khadka, the spokesperson for the Department of Mines and Geology, Kamala Devi Mineral Industry appears to have obtained permission from the department to extract limestone in 2021. The department has given the work order to extract limestone on 2.3 hectares of land. “The mine appears to be operating with permission, and it was allowed to operate after conducting an Initial Environmental Examination (IEE), but we were not aware that the land was subject to the land ceiling,” says Khadka.

25 years of government inaction

For 25 years, no government or governing body raised any questions, nor did any monitoring or inspection take place regarding Trishakti Cement freeing and selling the land exceeding the ceiling limit to Chaudhary. The Land Revenue Office, local administration, department, and ministry, that is, none of these bodies appear to have enforced the legal provisions.

The Land Act provides for a committee to monitor and inspect whether industries, establishments, companies, projects, educational institutions, or any other organizations that have received approval to purchase or keep land exceeding the ceiling limit are working according to their objective.

The committee, led by the Chief of the District Coordination Committee as the coordinator, has seven members. Its members include the office chief of the committee as member-secretary, the chief or chairman of the local level, a representative of the District Administration Office, the chief of the Survey Office, the chief of the District Treasury controller office and Office of the Comptroller General, and the chief of the office that regulates the concerned industry, establishment, project, or company.

They are required to monitor and inspect those who have received approval to purchase or keep land exceeding the ceiling limit, in consultation with the local level, within two months from the end of the fiscal year and submit a report to the concerned department. The department must study the report and submit it to the ministry with its recommendation within one month. If the land exceeding the ceiling limit is found not to be used according to its objective, the ministry must confiscate the land and transfer it to the name of the government.

These governing government bodies did not show any interest in the sale of Trishakti Cement’s land exceeding the ceiling limit for a long time.