The powerful voice that secured the Gandharva's distinct melody and Sarangi on the national platform

KATHMANDU: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the arts, such as music and cinema, served as a crucial conduit for dispensing optimism to global audiences. Amidst this upheaval, several classic Nepali folk melodies, rendered in a Bengali accent, achieved significant traction across digital platforms.

Notably, two masterpieces by Jhalakman Gandharva ascended to prominence: Timrai Nai Maya Lagdachha Saili and Allare Nani Kesi. The vocal rendition was provided by the Kolkata-based singer Arko Mukherjee.

Subsequently, this surge is posited as the catalyst for the recurrence of Jhalakman’s compositions in Nepali reality competitions and through YouTube cover versions.

Jhalakman was, and still is, synonymous with Nepali folk music and culture. After Indian singer Arko sang Jhalakman’s songs, his audience spread beyond the borders. And this trend will continue.

His song Aamai Le Sodhlin Ni was even ‘recreated’ in the film Koshedhunga, which was released this year, in the voice of Ashish Aviral.

It has been exactly 22 years today since the death of Jhalakman, who was born in Batulechaur, Pokhara, on July 29, 1935. He died at the age of 68 on November 23, 2003.

Jhalakman was not just an ordinary individual; he was a representative of Nepal’s richest musical community. He was the light bringer of a specific Nepali geography, a specific kind of folk practice, and a folk tradition.

The interest and research being conducted about Jhalakman today are due to his well-wishers and admirers. It is because of increasing access to technology. In the eyes of the state and stakeholders, he is still just a ‘Gaine‘ (singer).

One reason for the crisis of identity that Nepali music has been facing is the neglect of the dying Gandharva tradition. If the music of the Gandharvas had been promoted, we would have many Jhalakmans among us today.

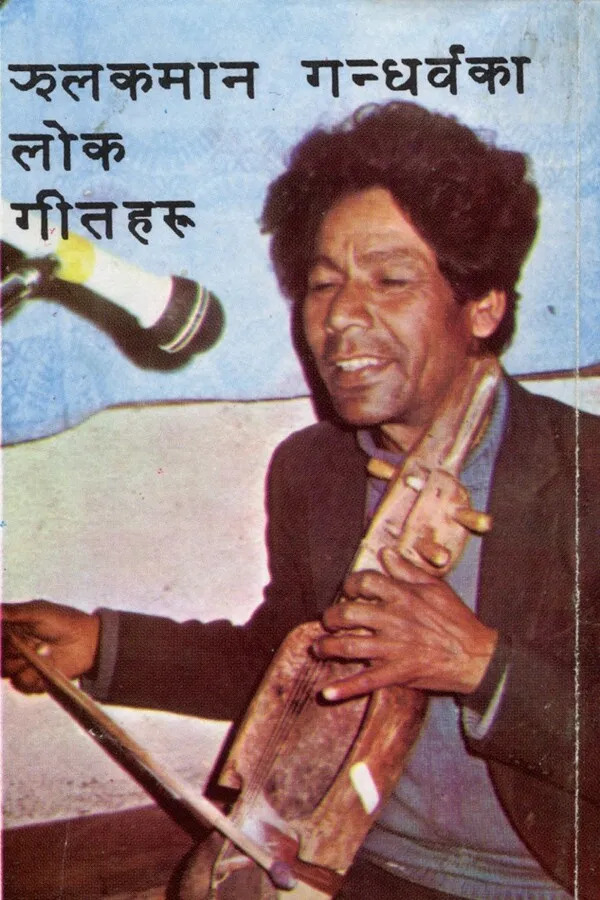

Cover of the book Jhalakman Gandharvaka Lok Geetharu

Ironically, the Gandharvas find it difficult to earn a livelihood by playing the Sarangi on one hand, and on the other, they were forced to change their surname due to caste discrimination and untouchability. This is why the Gandharva music/culture is disappearing. Despite having the talent and art, many potential Jhalakmans are condemned to anonymity and migration from their profession.

Jhalakman was also a figure who rose amidst poverty and hardship. However, a combination of coincidence and struggle created his unique story.

Jhalakman’s father, Durga Bahadur Mijar, was skilled at playing the Sarangi and singing the Karkha (historical narrative). This was the means of livelihood for many Gandharvas like him.

From a young age, Jhalakman and his brother Lal Bahadur became capable of playing the Sarangi and performing the Karkha just by accompanying their father. The ancestral skill was passed on to them without any formal musical training.

The Gandharvas find it difficult to earn a livelihood by playing the Sarangi on one hand, and on the other, they were forced to change their surname due to caste discrimination and untouchability.

The Gandharvas, who were discouraged by the state from farming and education, also used to catch fish by blocking water in the Kalikhola stream to solve their livelihood problems.

Dharmaraj Thapa, an acclaimed poet and vocalist, hailed from Jhalakman’s same village. Jhalakman once recounted, “Dharmaraj used to forcefully procure the fish we had harvested, which caused us distress.” However, this period of grievance was ephemeral. Thapa, who anchored the ‘Lokalhari’ program on Radio Nepal, became the invaluable intermediary that facilitated the introduction of Jhalakman, his brother, and the Gandharvas of Batulechaur to Radio Nepal’s platform. Tragically, Lalbahadur succumbed to death at an early age.

It is said that Jhalakman, encouraged by Dharmaraj himself, participated in the Nationwide Folk Music Competition organized by Radio Nepal in 1965. In the competition, his song Aamai Le Sodhlin Ni, which he presented with his own voice, words, and collection, won first place. He also got a job as an instrumentalist starting in 1967.

The song Aamai Le Sodhlin Ni was a wounded soldier’s message sent to his loved ones from the battlefield. Even today, the nation sighs upon hearing this message. It tears the hearts of Nepalis who are abroad.

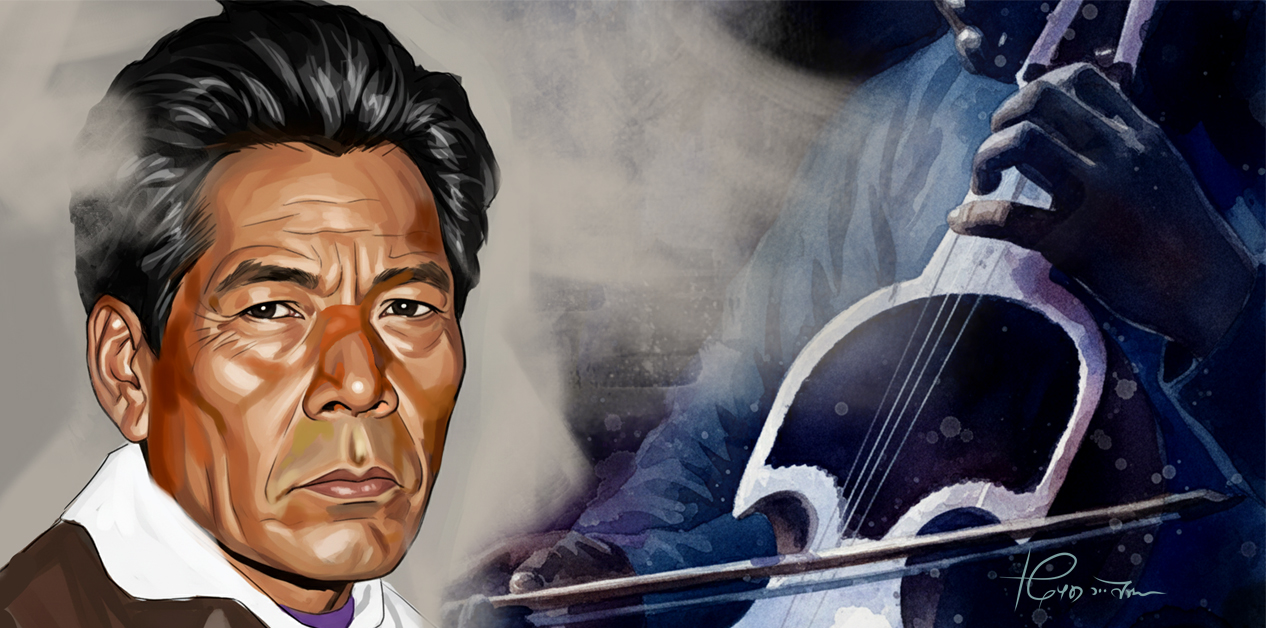

Jhalakman Gandharva

Regarding the genesis of this song, Jhalakman said, “One day, a villager’s son’s letter arrived at their hut. The letter contained the news that the Lahure (Gurkha soldier) son had fallen on the battlefield. I could not control my emotions after hearing the letter. This song was born from that painful realization.”

In the Second World War, approximately 120,000 Gurkhas fought on the side of the British Army; of these, 9,000 lost their lives. It is easy to imagine how much sorrow the war brought to Nepali villages and homes.

This song, which conveyed the dark side of fate, became the powerful melody that established the Sarangi and the Gandharva’s unique singing style in the recording tradition.

According to scholar and musician Bulu Mukarung, some Gandharva and Badi community artists were brought to Kathmandu for the first time during King Mahendra’s coronation in around 1956. During that time, some of their songs were also recorded at Radio Nepal.

In the pages of history, there are discussions of Hira Devi Gaineni of Kaski Hemja singing the Karkha of Mathwar Singh Thapa. Similarly, there is the account of Maniram Gaine acting as a messenger for Prithvi Narayan Shah while singing the Karkha.

After the recording tradition began, the credit for introducing and popularizing the Sarangi and Gandharva musical tradition into the mainstream goes to Jhalakman. Kiran Nepali, a Sarangi player and former member of the Kutumba Band, says, “I see Jhalakman’s contribution as the greatest in popularizing the Gandharva music/culture in the mainstream. That beginning was made with Aamai Le Sodhlin Ni.”

In the Second World War, approximately 120,000 Gurkhas fought on the side of the British Army; of these, 9,000 lost their lives. It is easy to imagine how much sorrow the war brought to Nepali villages and homes.

Within the Gandharva culture, various styles of song tradition, including Gatha, Karkha, and Jhyaure, are practiced. Jhalakman sang these diverse-style songs after Aamai Le Sodhlin Ni. Among them, Allare Nani, Tansen Ghamailo, Bala Joban, Danphe Chari, Nir Chari Ghumer Danphe, Dhaan Ko Bala Masyam Le Jeleko, and Aau Basam Thakain Maram became popular.

The establishment of Jhalakman, a witness to the experience of a skilled, renowned artist arising despite caste discrimination as a National Artist, was a matter of pride and self-respect for the Gandharva community. Because of Jhalakman, the Gandharvas did not have to struggle much to become established on the radio. The listeners also liked their artistic style. But despite their talent and popularity, the Gandharva artists and musical tradition are in crisis today instead of becoming stronger.

Sarangi player Nepali says, “The state failed to understand and protect the Gandharva cultural practice as a heritage. This is why, despite immense potential, original Nepali music does not have that influence.”

To understand the state’s attitude and behavior towards the Gandharvas, one must understand the society of that time. Bhim Bahadur Pandey writes in his book Nepal of That Time, “The Gaini (singers) did not have any land registered in their name in the hill villages. Therefore, it was mandatory for them to be landless for life.”

The Gandharvas, referred to as Gaini, were not just messengers for the Lahures. In the guise of beggars, they would travel from village to village, house to house, and marketplace, singing the Karkha about the bravery of their ancestors to the tune of the Sarangi. They recounted the tales of the unification of Nepal, the Kot Parba Massacre, the wars against the British, Tibet, Sikkim, and the Indian principalities, and the World Wars in a melodious tune to the general public. Their songs were the only means for the villagers to understand Nepal, Nepali nationalism, and the outside world’s news. In Pande’s view, “If there is any special credit in Nepal for preventing the flame of Nepali nationalism and aristocratic customs from extinguishing in the villages at that time, it belongs to that pity-inducing Gaine with the Sarangi.”

Jhalakman Gandharva: Photo: TKP

However, the then-rulers and the policymakers who dominated Radio Nepal used the Gandharva music/culture only as a ‘token.’ Radio Nepal was illiberal towards folk genres and culture. The classification of modern music and folk music is an example of this, which gave modernity a special status and folk music a secondary status.

For folk music to advance, the promotion of melodies, languages, words, and instruments is not enough. Special sensitivity towards folk life and folk practice is also needed. However, the effect of the untouchability prevalent in the then-society was bound to fall within Radio Nepal.

Singer Kumar Basnet, who traveled to Darjeeling, Sikkim, Kalimpong, and even Germany with Jhalakman, says, “Jhalakman and his friends were looked down upon by the famous artists of that time. They used to mock me too, calling me a Gaine because I sang folk songs.”

It can be easily inferred that Jhalakman and many artists worked caught between respect and discrimination in such an environment. Because of caste discrimination and the neglect of folk songs/music, Nepali music continues to face an identity crisis to this day. The fact that the stream led by original and masterful folk creators like Jhalakman could not become the mainstream of Nepali music is a result of this.

Singer Kumar Basnet, who traveled to Darjeeling, Sikkim, Kalimpong, and even Germany with Jhalakman, says, “Jhalakman and his friends were looked down upon by the famous artists of that time. They used to mock me too, calling me a Gaine because I sang folk songs.”

In this context, how will the musical legacy of the Jhalakmans find continuity?

Nepali, who is running a campaign to attract the new generation to the Sarangi through ‘Project Sarangi,’ expresses concern that much of the Gandharva culture has been destroyed. “One strong possibility is to recreate the works of Gandharva artists and deliver them to the new generation,” he says. “For example, Ram Saran Nepali’s old song became popular after his son sang it. Hira Devi Waiba’s song was also sought out and listened to by audiences after her daughter sang it.”

The research biography, Personality and Works of Folk Singer Jhalakman Gandharva, prepared by Ganesh Prasad Gyawali for Tribhuvan University, mentions that Jhalakman sang approximately 200 songs. However, many of those songs have stopped being played on the radio.

As Nepali says, if the old songs reach the new generation in a style that they appreciate, many creations that are fading from memory will be revived. But there are copyright issues in delivering old songs to the new generation.

“If you play old songs, Music Nepal claims the copyright. It is confusing how Music Nepal holds the copyright for songs recorded at Radio Nepal,” Nepali says. “The crucial point for the Gandharvas is that our previous musical heritage, such as the songs, Karkha, and history that we possess, should be made public by the state.”

Such mediums and efforts have their own limitations. The government itself must take the initiative to uplift the nation’s original and traditional music.

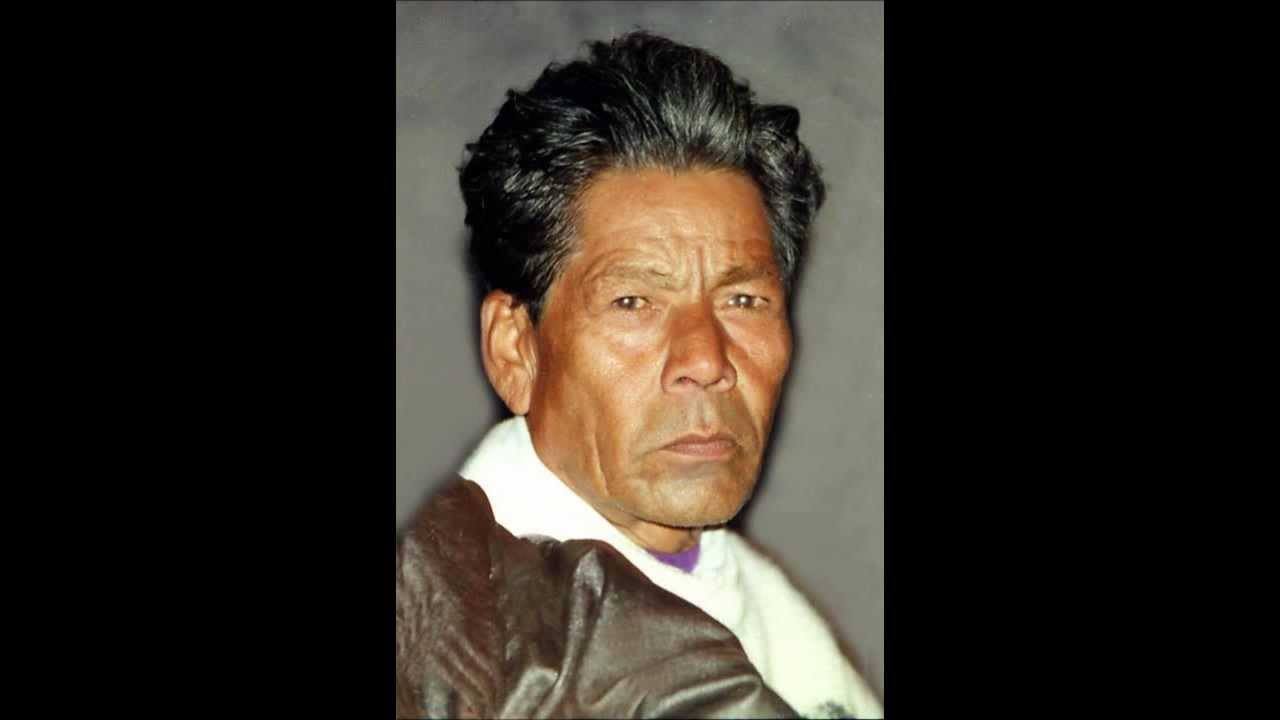

Jhalakman Gandharva playing sarangi

Nepali emphasizes that the government must take the initiative and invest in this work. “We have three academic institutions related to language, music and drama, and fine arts for which the state allocates a budget,” he says, “but those institutions are enjoying political sharing rather than preserving culture. If this continues, many practices and traditions associated with Nepali folk music will be limited to words.”

There exists another dimension when scrutinizing the musical heritage sustained within Nepal’s oral tradition. Numerous international researchers visiting Nepal documented and repatriated folk tunes and songs. These archival recordings are presently housed within museums and university libraries across nations such as France, Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

“The melodies and music derived from our oral tradition, which were recorded and removed by foreigners, are undeniably our own property!” Sarangi player Kiran Nepali asserts. “The government must initiate measures to reclaim these invaluable assets and integrate them into Nepal’s national collection.”

Thirteen years following Jhalakman’s death, intelligence surfaced indicating that Jhalakman’s compositions were securely held by Valentine Harding in Wales, United Kingdom. This discovery presages the potential for unearthing additional compositions by Jhalakman. Similarly, scholarly inquiry is necessary to determine precisely how many Nepali creators’ songs and music remain in international archives. To establish the identity and legacy of many more Jhalakmans, these materials must be diligently searched for, preserved, and actively promoted.