For 11 years, profiteering in manpower company licenses thrived through legal maneuvering and judicial precedent

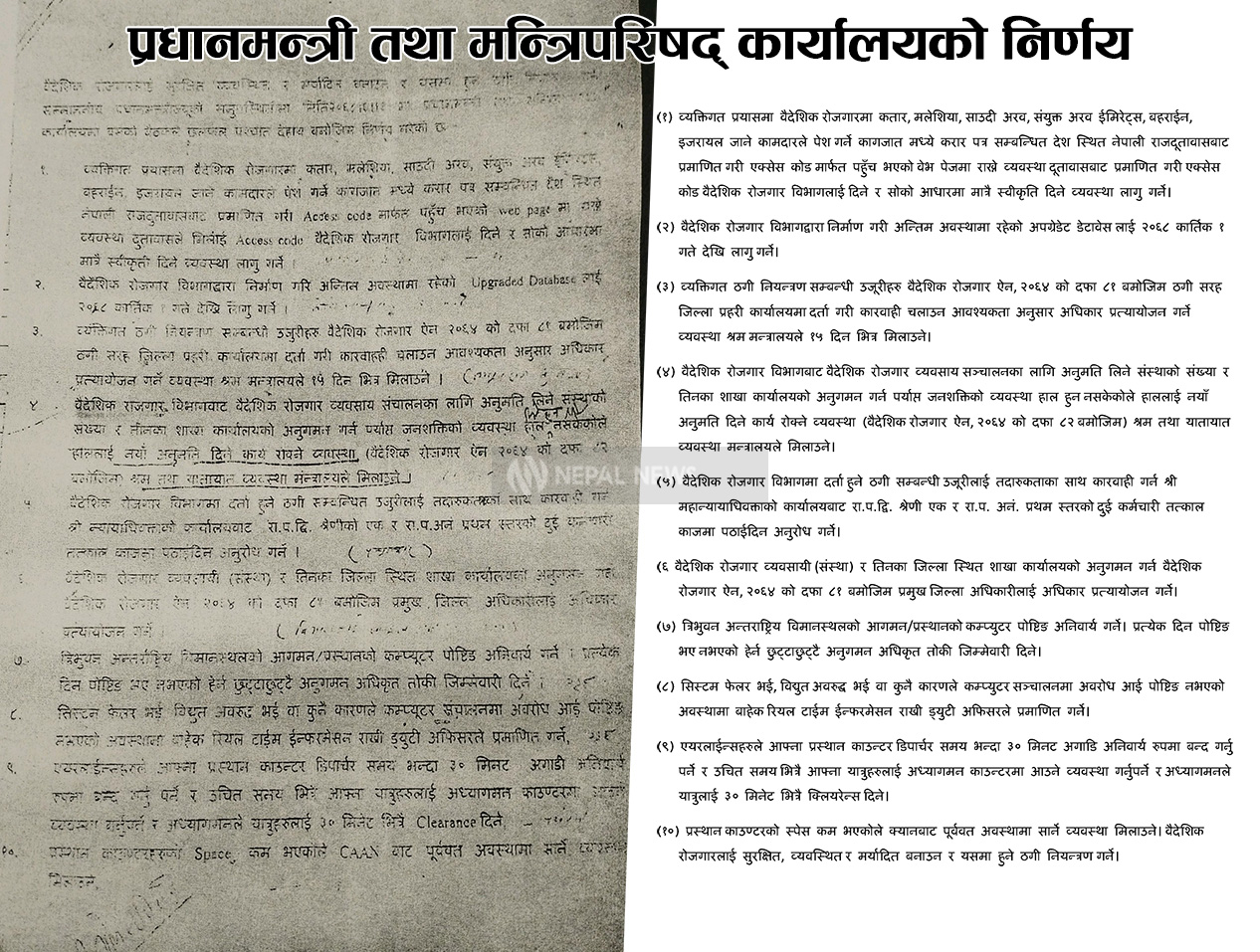

KATHMANDU: The then Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai initiated a decisive crackdown on the foreign employment sector by ceasing the issuance of new permits to foreign employment companies, popularly known in Nepal as manpower agencies, on October 20, 2011. Serving concurrently as the labor minister, Bhattarai leveraged his authority through the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers to officially freeze the registration of new manpower agencies.

However, the ban was immediately undermined: the business of new companies receiving licenses from the Department of Foreign Employment never stopped. This glaring paradox of the government formally halting registrations while the department continued to issue licenses persisted until the ban was formally lifted in 2022. Astoundingly, more than half of the total number of companies that existed in 2011 were registered during this eleven-year period of supposed prohibition.

When the decision to halt registration was made, there were 1,033 manpower companies in Nepal. However, by the time registration was opened in 2022, the number had reached 1,574. A total of 541 new companies received licenses during that period alone. During the same period, manpower companies were bought and sold for more than Rs 10 million. Manpower companies that were bought and sold for up to Rs 12.5 million in 2011 were registered in such large numbers through the back door during the ban that by 2022, the price had dropped to around Rs 3 million. Nepal News’ investigation found evidence of how much the decisions made by the highest officials of the government, without regard for the constitution and the law, affected the market.

Dr. Bhattarai, who was appointed Prime Minister on August 29, 2011, initially kept the then Ministry of Labor and Transport Management with himself. Bhattarai, who became prime minister amid mismanagement and political turmoil, was under pressure to carry out reforms. At that time, there were criticisms and comments from entrepreneurs that fraud was rampant in the foreign employment business. To make the foreign employment business systematic and respectable, Bhattarai decided not to issue licenses to new companies on September 30, 2011.

In a letter with dispatch number 146 sent from the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers to the then Ministry of Labor and Transport Management on October 2, 2011, point number 4 explained the reasons for stopping the registration of manpower companies, citing it as a decision made in the presence of the Prime Minister: “Since sufficient manpower has not been arranged to monitor the number of institutions taking permission to operate foreign employment business from the Department of Foreign Employment and their branch offices, the provision of temporarily stopping the issuance of new permits (to be managed by the Ministry of Labor and Transport Management pursuant to Section 82 of the Foreign Employment Act, 2007).”

The ministry then instructed the Department of Foreign Employment to implement the decision, and based on that, the registration of new manpower companies was stopped. Section 82 of the Act provided for the power to remove obstacles and issue necessary orders by publishing a notice in the Nepal Gazette. The government decided to stop company registration based on the same section.

The original letter from the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers, dated September 30, 2011, banning the issuance of new manpower company licenses

By the time this decision was implemented, 1,034 manpower companies were registered with the Department of Foreign Employment. The then government believed that there was insufficient manpower even to monitor these companies, and new registrations would only exacerbate the problem. At that time, Rohan Gurung, who later became the president of the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies, was the general secretary.

According to Gurung, at least 280 institutions out of the total registered were revoked, and only 754 institutions were active. The then government stopped new registrations, stating that even these could not be monitored. Gurung and other businessmen were active in “lobbying” to stop the registrations, arguing that too many companies led to unhealthy competition.

The government’s decision to stop the registration of manpower companies opened the way for middlemen to engage in maneuvering and profiteering campaigns. After the new registration stopped, old companies were bought and sold for more than Rs 10 million. Gurung himself says, “When company registration was closed, old companies were bought and sold for up to Rs 10 million.”

Since buying a single manpower company cost more than Rs 10 million, the entrepreneurs looked for a new option, which was the judicial route. Arguing that their right to engage in business was being violated, entrepreneurs began filing writs in court demanding company registration. On one hand, this allowed them to run companies as foreign employment businesses at a low cost, and on the other hand, it became an excellent source of income for those who were trading the companies themselves.

The trend reached a point where legal advisors to the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies and lawyers close to entrepreneurs went to court with writs for manpower company registration. Some of them reportedly charged a fee for legal representation, while others went as far as registering the company and selling it. After 2015, there was a wave of taking writ petitions to court, registering the institution after an interim order was issued, and then selling the registered manpower companies for more than Rs 10 million.

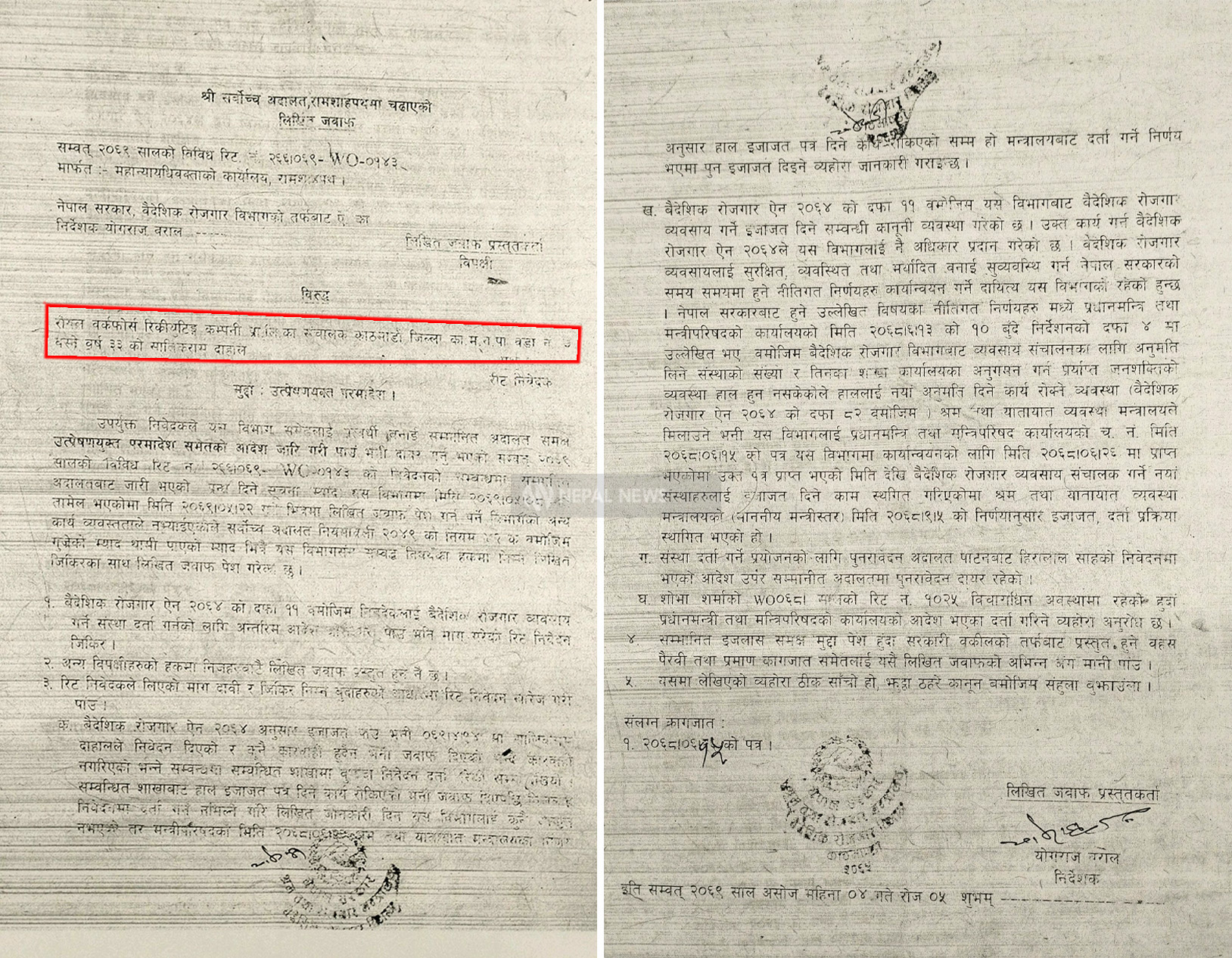

Written response submitted by the Attorney General’s Office to the Supreme Court

Shambhu Prasad Niraula, who was the legal advisor to the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies at the time, was one of the main lawyers arguing in the writs for manpower company registration. Out of 342 writs of companies analyzed by Nepal News from the data received from the Department of Foreign Employment, Niraula argued in 32 writs in the Patan High Court and the Supreme Court.

Only a few limited legal professionals are seen taking such writs to court and arguing them. They include Niraula, along with Salikram Dahal, Balkrishna Neupane, Rajaram Bhattarai, Surendra Kumar Mahato, Manohar Sah, Ghuran Sah, Sandesh Raj Bhandari, and Tanka Prasad Regmi. Similarly, lawyers, including Rajkumar Sah and Mukunda Neupane, also took writs for manpower company registration to court.

Easy passage by legal decree

Let us look at some examples of how manpower agencies were registered by challenging the government’s decision in court:

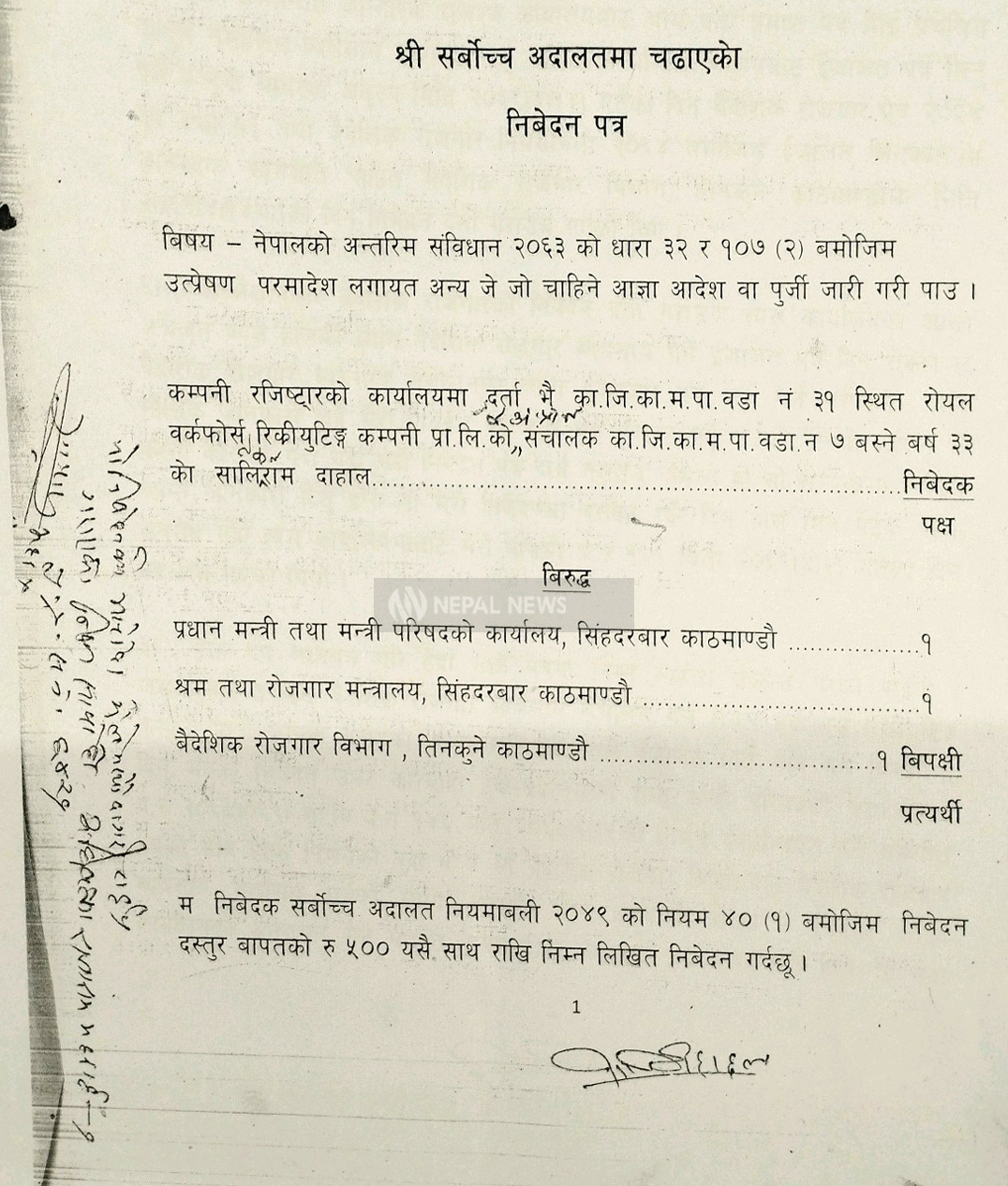

Salikram Dahal, a permanent resident of Kathmandu Metropolitan City-31, registered Royal Workforce Recruiting Company at the Office of the Company Registrar on July 11, 2012. He also obtained an income tax registration certificate from the Inland Revenue Office. He then applied to the Department of Foreign Employment on July 29, 2012, requesting a license to operate as a foreign employment company. The Department refused to issue the license, citing the decision of the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers that the registration of new manpower companies was halted.

On August 5, 2012, the department informed Dahal by letter that the issuance of new permits was halted, referencing the Cabinet’s decision. Based on that letter, Dahal filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court on August 17, 2012, naming the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers, the Ministry of Labor and Employment, and the Department of Foreign Employment as opponents.

The writ was heard on August 22, 2012, in the single bench of Justice Tahir Ali Ansari. He granted the writ priority and issued an interim order. The interim order stated, “Considering the seriousness of the subject matter of the present writ petition, it is necessary that a quick decision be made, and therefore priority is granted for the hearing pursuant to Rule 63(3)(F 5) of the Supreme Court Rules, 1992.” Dahal went to the Department of Foreign Employment again with the order. He was once again denied a foreign employment company license. He was informed that a license would not be issued until the final verdict of the case pending in the Supreme Court was released.

Salikram Dahal files writ petition in Supreme Court demanding registration of foreign employment company

After Dahal, Sheskanta Puri filed a writ in the Supreme Court on December 4, 2015, claiming that he was not allowed to register a manpower company. However, the final verdict came on the writ filed by Puri before that of Dahal. The joint bench of Supreme Court Justices Gopal Parajuli and Govind Kumar Upadhyay issued the writ. The verdict stated, “Government bodies cannot legally evade their responsibility by saying that sufficient manpower has not been arranged to monitor the number of institutions and their branch offices taking permission to operate foreign employment businesses.”

The action of the Department of Foreign Employment, allowing the company to register, submit a cash deposit, accept a bank guarantee, test their ability to bring demand from abroad, and participate in all processes, but not making a decision on whether or not to issue a license, cannot be considered legal.”

The writ filed by Dahal was scheduled 12 times but was postponed because it could not be heard. However, the writ was finally issued on February 14, 2016. The verdict, issued by the joint bench of Justices Kalyan Shrestha and Devendra Gopal Shrestha, stated, “Since the right of the petitioner to practice a profession and employment appears to have been violated by the letter Ch. No. 146 dated October 2, 2011, sent by the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers to the Ministry of Labor and Transport Management, and the letter of the Department of Foreign Employment to the petitioner dated August 5, 2012, the said letter and the decisions related to it are hereby annulled by the order of certiorari.”

After Dahal, Sheskanta Puri filed a writ in the Supreme Court on December 4, 2015, claiming that he was not allowed to register a manpower company. However, the final verdict came on the writ filed by Puri before that of Dahal.

However, the court did not annul the decision made by the Office of the Council of Ministers. The verdict only annulled the correspondence made based on the decision. The writ petitioners also did not claim the annulment of the government’s decision but only demanded the registration of their respective companies.

The same verdict interpreted that when no law restricts or prohibits the operation of any profession or business, citizens cannot be prevented from exercising their right to operate a profession or business granted by the constitution and law on the basis of an executive order without a legal basis. The court issued a mandamus order, directing the department to proceed with the issuance of a permit for the foreign employment business as demanded by the petitioner.

Following the court’s decision, it became the legal obligation of the Department of Foreign Employment to issue licenses to new companies. No government body went to court with a ‘vacate’ petition against the court’s decision. Subsequently, the court issued orders in the writs demanding the registration of manpower companies, citing these verdicts as precedents. No other companies that approached the Department without a court verdict received a license.

The court’s decision was exactly what Dahal, who was struggling to get a company license, had been looking for. He went to the Department of Foreign Employment to get a license with the Supreme Court’s mandamus. Finally, on June 1, 2015, Dahal’s Royal Workforce Recruiting Company received permission to operate the foreign employment business. The judicial path for registering new companies to conduct foreign employment business was thus opened.

Company registration file at the department. Photo: Uddab Thapa

The records of the Department of Foreign Employment show that Salikram Dahal alone registered 39 companies based on court orders. He registered seven companies on a single day, January 10, 2017. Similarly, he registered 14 companies in his own name in the month of March 2017 alone. At that time, the provision for obtaining a foreign employment business license required depositing Rs 700,000 in the bank and submitting a bank guarantee paper of Rs 2.3 million.

To create a bank guarantee of Rs 2.3 million, the bank demanded a deposit of Rs 500,000. This meant that Rs 1.2 million was required just for the banking process to obtain a license for one company. To register seven companies on a single day, Rs 8.4 million was needed for banking transactions alone. For 14 companies, Rs 16.8 million in cash had to be deposited. Dahal completed all these tasks and registered the companies.

Dahal is currently the operator of Young Manpower in Gaushala, Kathmandu. When this company was registered, its name was Pujan HR Service. The company was registered on January 20, 2017, based on the Supreme Court’s verdict. Advocate Rajaram Bhattarai argued on behalf of Dahal in the writ filed by him in the Supreme Court. Bhattarai is also one of the lawyers who argued in most of the writs filed in the High Court and Supreme Court demanding the registration of foreign employment companies. Analyzing the data provided by the Department, Bhattarai alone argued in the writs of 50 companies.

Dahal also took the writs of entrepreneurs who wanted to register manpower companies to court. He says he took more than 700 writs to court at that time for a consultation fee of Rs 100,000 each. “They had deprived people of their right to do business by closing company registration. When a citizen said they would do business, the government said they could not. The court was the only recourse. I took the petitions of more than 700 people to court. Many of those companies have been registered,” Dahal told Nepal News over the phone, but he refused to meet for a detailed discussion.

The records of the Department of Foreign Employment show that Salikram Dahal alone registered 39 companies based on court orders. He registered seven companies on a single day, January 10, 2017.

The profiteering play

The game of registering new companies and selling them continued until 2022, after the court’s verdicts started coming out. Entrepreneurs themselves admit that the price of old companies, which were being bought and sold for more than Rs 10 million after the government’s decision, dropped to Rs 7 million to 7.5 million in the initial years after the court’s verdict. By 2021, manpower companies were traded for as low as Rs 3.5 million.

An official of the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies, who bought a company from Dahal in 2021, requested anonymity and told Nepal News, “Initially, companies were bought and sold for up to Rs 12.5 million. When I started the business, I bought the company for Rs 3.5 million.”

After learning that the government had decided to stop company registration but that companies were being registered rapidly in the department, the issue was discussed in the International Relations and Labor Committee under the House of Representatives in 2017. At that time, lawmakers raised concerns in the committee that writ petitions were being filed in court, but companies were being registered before the verdict came. The chairman of the committee was then-CPN (Maoist Center) leader Prabhu Sah. “The work of employment entrepreneurs is connected with millions of workers. When the regulation of those is not done properly, creating new companies creates further chaos. That is why we asked to stop it,” says Sah.

After the ministry’s name was implicated in the parliamentary committee, Surya Man Gurung, who was the minister at the time, said that company registration was not within the ministry’s jurisdiction, but if the department had done something illegal, it would be investigated and action would be taken. The investigation he promised never happened. The following year, after the 2017 election, UML leader Gokarna Bista took charge of the Ministry of Labor. He verbally instructed the department not to register foreign employment companies. However, his instruction did not work either.

Entrepreneurs themselves admit that the price of old companies, which were being bought and sold for more than Rs 10 million after the government’s decision, dropped to Rs 7 million to 7.5 million in the initial years after the court’s verdict.

After the court’s order, there was no way to stop company registration, and it continued. Bhuwan Prasad Acharya, the then Director General of the Department, continued company registration, saying that non-compliance with the court order would lead to a contempt of court case. Later, however, the government itself officially opened company registration in 2022.

Haphazard registration

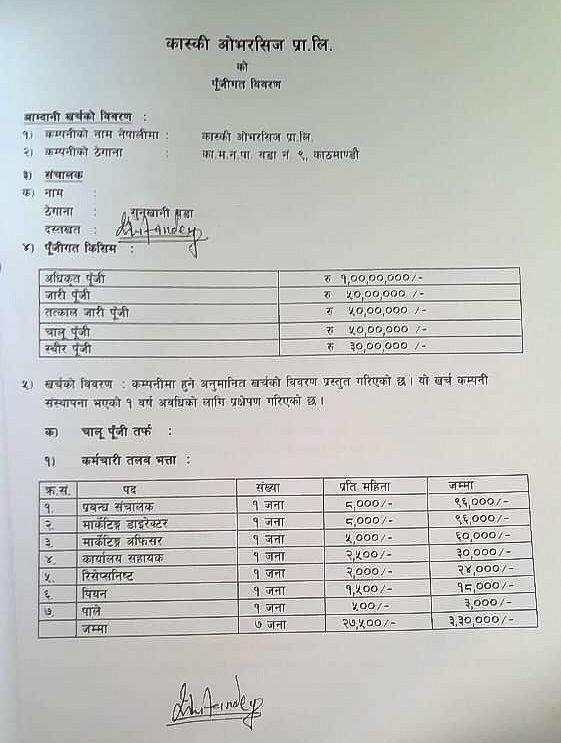

In the period from mid-May 2015 to mid-September 2022, due to a shortage of names, companies were even registered in the names of districts across the country. Dahal himself registered companies named Lalitpur, Kalikot, Sindhuli, Jumla, Ilam, Palpa, Rasuwa, Mugu, Sunsari, Palpa, Salyan, Rolpa, and Dolakha Overseas. Besides these, various individuals registered companies in the names of Kaski, Dailekh, Salyan, Makwanpur, Doti, Siraha, Dolpa, and Janakpur districts. Most of these company names have since been changed.

The registration details for the company named Kaski Overseas, one of many registered in the name of a district

There was such negligence in the registration of manpower companies that Nirmal Shrestha and Salikram Dahal received licenses for two different companies with the same name, Dolakha Overseas. For instance, Dahal’s Dolakha Overseas (License No. 1131) was already registered with the Department on March 21, 2017. On October 24, 2017, Dolakha Overseas was registered again under the name of Nirmal Shrestha with license number 1354. The file of that company shows that Shrestha only submitted the daily cause list of the Patan High Court for the license.

Shrestha has now changed the company’s name to Mirror Overseas. Dahal’s company named Dolakha has been changed and sold as Manpower Recruitment Nepal.

Not only that, when NS International was registered, the court verdict issued in the name of Royal Workforce Recruiting Company was placed in the file. KB Overseas, with registration number 1253, and Minawa Manpower, with registration number 1290, operated by Hemraj Rai, were also found to be registered by placing only the daily cause list of the court in the file.

Shining Star Overseas, with registration number 1276, was also found to be licensed by placing only the application submitted for registration and a letter sent by the Patan High Court stating that the case had been decided.

The original decision by the then Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers to halt new manpower company registrations ultimately lacked a strong legal basis. Consequently, the judiciary annulled the subsequent actions taken by the subordinate bodies based on that flawed directive.

The essence of this entire incident is clear: the central objective for which the decision was made, to bring order to the foreign employment business, was not fulfilled. Instead, unhealthy competition surged, a new layer of complexity was added by requiring businesses to seek judicial recourse merely to conduct their work, and, most profitably, middlemen took advantage of the newly created legal and market vulnerabilities.