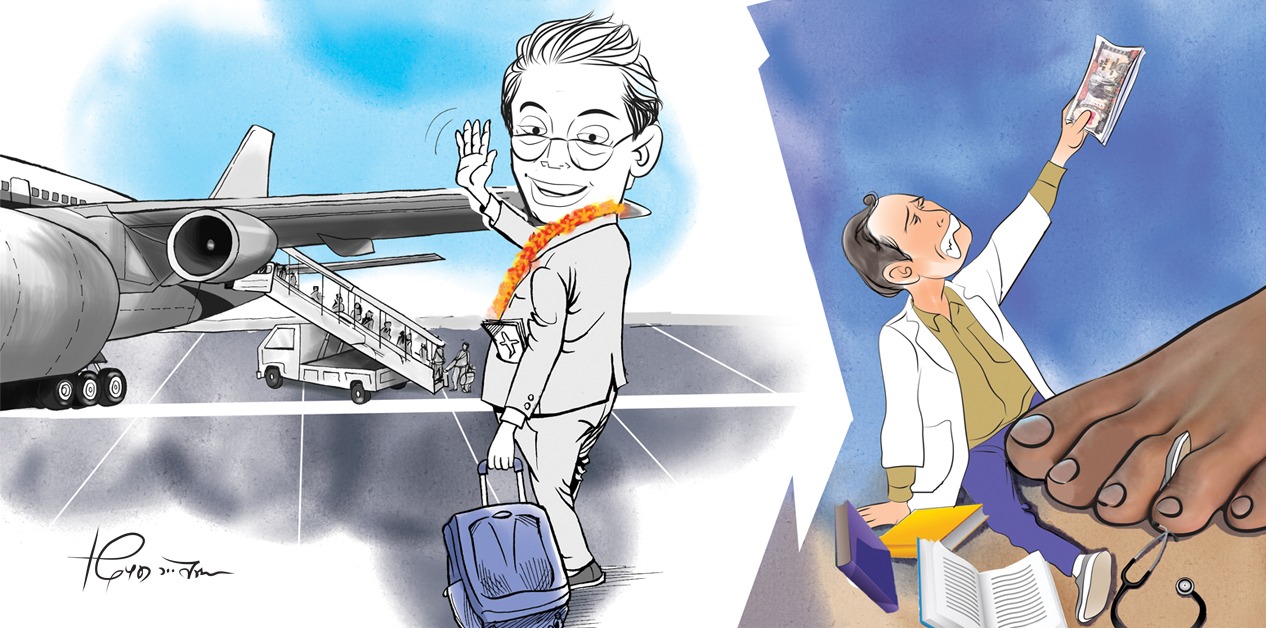

The irresistible lure of 7-fold income: Gulf wages dwarf Nepali salaries, driving medical talent abroad

KATHMANDU: The migration of highly skilled Nepali medical talent is dramatically etched onto the healthcare system of the West Asian Gulf. Oman serves as a prime example of this professional exodus; within the high-pressure emergency ward of Sinaw Hospital, one finds Dr. Anjan Tiwari, 35, a physician originally from Pokhara Metropolitan City-33, who three years ago joined the ranks of those seeking enhanced opportunities in the Gulf.

Working alongside Dr. Tiwari at the same hospital are Diwas Bastola (from Kathmandu), Dinesh Sapkota (from Chitwan), Pradip Paudel, and Rupak Shrestha (Nuwakot). Diwas and Dinesh also work in the emergency department, while Pradeep and Rupak work in the OPD.

According to the Nepali Doctors Association Oman, nearly 300 Nepali doctors are currently working in hospitals across Oman alone.

They represent the hundreds of Nepali doctors who have made the West Asian Gulf region their professional destination.

For example, neurosurgeon Dr. Sabal Sapkota has been working at the Sheikh Khalifa Medical City in Abu Dhabi, UAE, since July 2022. According to Dr. Sapkota, who previously worked as a specialist doctor at the National Trauma Center in Nepal, there are up to 150 Nepali doctors in UAE hospitals. Most of them are general practitioners, with only a few being specialist doctors.

Sabal notes that the appeal of high income and professional security has lured many Nepali doctors to the UAE.

Why do Nepali doctors choose the Gulf?

Dr. Tiwari, who works at Oman’s Sinaw Hospital, explains that he came to Oman in search of a better future after being weighed down by Nepal’s difficult environment, limited opportunities, unstable politics, and the burden of a Rs 6 million student loan.

After completing his MBBS in the Philippines and returning to Nepal, Dr. Tiwari started working as a medical officer at Lekhnath Community Hospital (now Provincial General and Infectious Disease Hospital) in 2022. His salary was just Rs 30,000.

Later, when the hospital was upgraded, his salary increased to Rs 70,000, but even that amount made it almost impossible to repay the Rs 6 million loan from his studies in the Philippines and meet his personal needs.

“When would I ever repay the Rs 6 million loan from my studies with an income of Rs 70,000? How could I raise and support a family?” he recalled, expressing his frustration.

Around that time, he saw a notification that the Oman Ministry of Health was looking for foreign doctors. The salary was attractive. After finalizing the necessary procedures through a manpower company and obtaining a labor permit from the Department of Foreign Employment, he flew to Oman on November 17, 2022. “The workplace environment here is much more comfortable and well-equipped than in Nepal. We only have to work seven hours a day and 35 hours a week,” he stated, reflecting his assurance about the future, adding, “In Nepal, we had to be on duty for more than 42 hours a week.”

According to Dr. Tiwari, his salary and benefits in Oman are seven times higher than what a Nepali government doctor at the Eighth Level receives.

Furthermore, benefits like overtime pay for extended duty hours, free treatment for the doctor’s family, two months of annual leave, adequate equipment, and a comfortable working environment are drawing doctors like Tiwari to the Gulf. He asks, “With so many facilities, why wouldn’t doctors leave the country?”

Dr. Tiwari adds that the Omani government recruits General Practitioners (GPs) from countries including Nepal. Recruiting companies often post such notices on social media, and manpower agencies in Nepal facilitate the process for the doctors.

Manaslu International is one such manpower company that sends doctors from Nepal. Its director, Raju Rayamajhi, states that Manaslu has been sending Nepali doctors and nurses to Gulf countries, including the UAE, for nine years. He confirms that doctors going to the Gulf earn at least seven times more than in Nepal.

11,573 doctors obtained ‘CGS’ in six years

According to the Department of Foreign Employment, out of the total 839,277 people who received labor permits in the fiscal year 2024/25, at least 5,309 were professionals and highly skilled youths. While the department does not keep separate statistics for doctors and nurses, Information Officer Upendra Raj Paudel states that they are included among those who apply for foreign employment permits.

Similarly, the number of doctors registered with the Nepal Medical Council during the six-year period from fiscal year 2019/20 to 2024/25 is 39,486. Of these, the number of doctors who have taken the ‘Certificate of Good Standing’ (CGS) is 11,573. Without this certificate, issued by the Council, no Nepali doctor can go abroad for study or work.

According to Council Registrar Dr. Satish Kumar Dev, more than 70 percent of the doctors who take the certificate leave the country permanently.

Dr. Gopal Sedhain, spokesperson for Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, explains that doctors are attracted abroad because private hospitals’ management often sets a ‘target,’ and failing to meet it can result in immediate job loss and low benefits. He says, “Since both the government and private sectors offer low benefits, many Nepali doctors choose foreign lands.”

According to spokesperson Sedhain, as doctors are drawn abroad, government hospitals are currently run by daily wage, contract, and scholarship doctors. He notes that this constitutes only temporary manpower.

Disappointed in Nepal

Neurosurgeon Sapkota, who works at the Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, says he left Nepal feeling disillusioned. He states, “The situation for doctors in Nepal is the same as it was 10 years ago, give or take. Don’t be surprised if it remains the same even 10 years from now.”

The situation Dr. Sapkota is referring to is economic and professional insecurity. He shared the compulsion of having to repeatedly ask for his salary while working in Nepal. “I can’t be late paying house rent, bank loans, installments, and children’s tuition fees. That’s one of the reasons I left Nepal,” he says, adding, “Many others probably share my compulsion.”

In the UAE, facilities such as excellent security arrangements, tax-free salaries, quality education for children, and superior health insurance have provided him with significant financial security.

However, the migration of doctors is not just about financial security. Systemic and administrative hurdles are also pushing doctors abroad. Since the formation of the three-tier government, the opportunity for personnel assigned to the local level to move to the center has been closed, creating a hurdle in the career development of doctors.

Dr. Shree Krishna Giri, former vice-chairman of the Medical Education Commission, points out the need to change the health policy itself to retain doctors in the country. He believes that the problem could be solved if the proposed Health Act includes a separate provision regarding the salary and facilities of health workers.

Similarly, labor expert Keshav Bashyal says that when highly skilled manpower from a sector where Nepal has invested heavily chooses foreign lands as their workplace, there is a risk of a crisis in the availability of expert doctors in the country. While Nepal is a member of the World Trade Organization and the government does not have the right to prevent skilled technical personnel from seeking employment, it is the government’s responsibility to provide them with a good environment within Nepal, he argues.

Bashyal suggests that while the government may not be able to offer facilities comparable to those abroad, it should at least ensure adequate benefits for a decent living, a good working environment, and professional security. He believes this would reduce the exodus of doctors to some extent, even if it cannot stop it completely.