Extorting environmental fees from consumers only to fuel administrative apathy

KATHMANDU: For three long months, from mid-December 2024 to mid-March 2025, every breath taken by Kathmandu residents was a gamble with toxic air. The smog has cleared, but the tally of those who paid with their lives remains a profoundly silent ledger.

According to a report released on April 3, 2025, by the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in Lalitpur, the air in Kathmandu was toxic for 75 days from January 1, 2025, to March 13, 2025.

Even on the day ICIMOD released the report, the valley’s air quality had crossed critical levels. On the Department of Environment’s air quality monitoring station and dashboard, the Air Quality Index (AQI) reached its highest level of 365 at the Bhaktapur station that very day. Such a critical level of polluted air can cause serious impact on human health.

In Kathmandu, which has dense and unorganized settlements, air pollution occurs year-round. However, once winter begins, pollution peaks because farmers burn agricultural residue after harvesting, forest fires increase due to dry droughts, and industrial and construction activities intensify. Due to the influence of western winds, dust and smoke from infrastructure construction, vehicles, and factories enter Nepal from the northern part of India. That also increases the air pollution level in the valley.

According to Gyan Raj Subedi, director general of the Department of Environment, this period generally lasts from mid-November to mid-April every year. Residents of Kathmandu Valley suffer from air pollution every winter.

“Naturally, to clean the air, wind must blow or it must rain; in winter, wind is low, and since it has stopped raining in winter for the past four or five years, the amount of pollution has increased compared to the past,” Subedi says.

Subedi further added that because cold air remains stagnant near the ground surface in winter, toxic particles accumulate in the air.

On November 27, 2025, Kathmandu’s air quality also reached an unhealthy level of 168 AQI. Along with this, Kathmandu ranked seventh on the list of the top 10 most polluted cities in the world. This year, the misery of cold, fog, cold waves, and toxic air has already begun in Kathmandu and the Terai region of the country. Pollution increases further in winter due to the burning of plastic, paper waste, tires, straw, dung cakes, and coal to stay warm, among others.

Although thousands of people die prematurely every year due to air pollution, the government has neither taken serious steps to control it nor appears sensitive toward citizens’ health safety. Instead, in the name of air pollution control, it has collected Rs 26.863 billion in fees from consumers over the period of 18 years.

Ministry left empty-handed as pollution fees sit idle

The government has been collecting a pollution control fee on the sale of petrol and diesel since the fiscal year 2008/09. Initially, this fee was collected at a rate of Rs 0.50 per liter. Since the fiscal year 2019/20, it has been increased to Rs 1.50 per liter.

The government collects the pollution control fee by specifying it in the budget statement every year. According to Navbinod Pokhrel, acting director of the Finance Department of Nepal Oil Corporation, the collected fee is deposited by the corporation into the revenue account of the Ministry of Forests and Environment every month. There is even a provision to add a 15 percent penalty Annual Percentage Rate if not deposited within the specified period. Ironically, the fee collected from citizens to control pollution is not spent on the designated work.

“We deposit the pollution control fee into the Forest Ministry’s revenue account every month; the Ministry of Finance or the Forest Ministry might know how it is being spent,” says Acting Director Pokhrel.

However, Subedi, director general of the Department of Environment, informs us the pollution control fee amount has not reached the Ministry of Forests and Environment.

“Even if it’s for pollution control, the money is with the Ministry of Finance. If even only five percent of what is collected were spent, air quality could have been controlled or improved,” Subedi further added.

Just because the Ministry of Finance did not provide the funds, the Department of Environment has been unable to repair broken air pollution monitoring stations.

According to the Department of Environment, there are 30 air pollution monitoring stations under the department, of which only a maximum of 15 are in operation.

“Currently, if a lump sum budget of at least Rs 30 million to Rs 40 million was given to the department, then the department could immediately repair and regularly operate all monitoring stations,” said Director Subedi of the Department.

The Office of the Auditor General has also pointed out the misuse of fees collected from consumers related to fuel. ‘The fee collected for pollution control and management should be utilized for that very purpose only,’ states the 62nd Annual Report (2025) of the office.

Auditor General Toyam Raya submitting the Annual Report for the Fiscal Year 2023/24 to President Ram Chandra Paudel at Sheetal Niwas. Photo Courtesy: Office of the Auditor General

The lack of government intervention in improving air quality is also due to weaknesses in citizens and stakeholders. Stakeholders do not seem to be focused on nudging the government to control air pollution.

“After the Dashain and Tihar festivals end, air pollution increases due to the operation of factories, burning of agricultural residue, cooking and burning of firewood for warmth in the Terai region, and forest fires, and public outcry begins when breathing becomes difficult. But when it rains and pollution decreases, this issue fades away,” says Bhushan Tuladhar, an environmentalist.

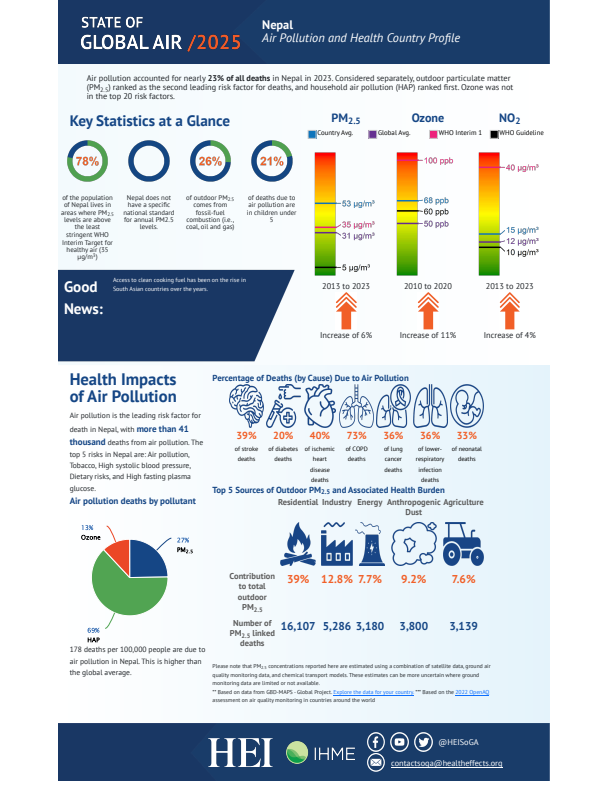

According to the State of Global Air Report 2023, released in 2025, over the last decade, the main elements causing air pollution nationwide in the atmosphere, Particulate Matter 2.5, have increased at a rate of six percent, Ozone by 11 percent, and Nitrogen Oxide by four percent. Particulate Matter 2.5 is considered extremely harmful to human health.

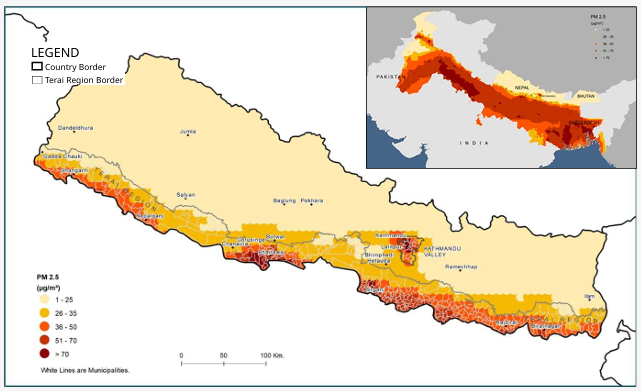

A 2021 study by the World Bank shows that if attention is not paid to air pollution control now, the annual average level of fine toxic particles in the Kathmandu Valley’s atmosphere will reach 51 micrograms per cubic meter and above 42 micrograms in the Terai region within the next 10 years. This will exceed the maximum limit of 35 micrograms set by the World Health Organization (WHO), even though Nepal has set a goal to maintain the annual average level of fine particles within WHO limits by 2035.

However, four years ago, the level of microparticles in Kathmandu’s atmosphere had already reached 37 micrograms and 39 micrograms in the Terai region. This is seven times higher than the WHO annual average limit of five micrograms per cubic meter. Two years ago, the level of fine particles in Kathmandu and the Terai region had already crossed 40 micrograms per cubic meter.

The World Bank study concludes that the polluted air increasing within the next decade will increase the premature death rate, cause severe health impacts on children and senior citizens, and undermine overall quality of life and economic output.

According to the study of the World Bank in 2021, the additional economic burden on Nepali citizens every year due to air pollution (including indoor production) will be 10 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Unfortunately, the State of Global Air Report 2025 states that more than 41,000 people die every year in Nepal due to air pollution.

Kathmandu and Madhesh remain Nepal’s pollution hotspots

According to a report released by the World Bank recently in 2025 titled Towards Clean Air in Nepal: Benefits, Pollution Sources, and Solutions, along with the Kathmandu Valley, the villages and cities of Madhesh bordering the Indian border are air pollution ‘hotspots.’ No improvement in air quality has been seen in these places over the last decade.

Air quality researcher and expert Dr Bhupendra Das explains that complications in public health are increasing and direct impacts on daily life are occurring because air pollution could not be controlled.

Among the microtoxic particles found in Kathmandu’s atmosphere, the place of origin for 63 percent is Kathmandu itself. Here, road dust contributes eight to 12 percent to polluting the air, according to the report of the World Bank in 2025. Forest fires that recur nationwide during the dry winter season from mid-January to mid-May also pollute Kathmandu’s air. In the Terai, at least 67 percent of the total microparticles found in the atmosphere come directly from India.

In Kathmandu, black smoke (black carbon) emitted from old and diesel/petrol-operating vehicles ranks number one in causing air pollution. Based on the analysis by the World Bank regarding the annual average level of microparticles of 2.5 microns or smaller, which cannot be seen by the naked eye, the share of the transport sector as the main factor of air pollution in Kathmandu is 27 percent.

According to data from Nepal Police, the number of vehicles registered until the fiscal year 2023/24 in the three districts of Kathmandu Valley, which have some 2,084 km of roads, is around 1.9 million.

Levels of PM 2.5 across the Kathmandu Valley and Terai four years ago, with the top inset highlighting the broader atmospheric crisis over the Indo-Gangetic Plain and Himalayan foothills. Photo Source: World Bank Report

The amount of air pollution originating from energy sources used at home is 25 percent, from brickkilns and industrial production 19 percent, from burning agricultural residue and forest fires 11 percent, from livestock and manure nine percent, from soil dust six percent, and from waste management three percent, according to the State of Global Air Report 2025.

However, the data from the report reveals that in the Terai region, the share of indoor air pollution produced due to wood, dung cakes, and coal used for cooking, among other things, is the highest at 31 percent. In Kathmandu, air pollution from factories is 23 percent, from livestock/manure 17 percent, from transport 16 percent, from burning agricultural residue, forest fires, and waste management six percent each, and from dust one percent.

Analyzing the overall situation across the country, smoke and dust from households have become the biggest factor contributing to air pollution.

According to the State of Global Air Report 2025, a 39 percent contribution to total air pollution is related to household energy sources. The share of industries and factories is 12.8 percent, and fossil fuel/energy is 7.7 percent.

Failure to translate pollution laws into action

The Constitution ensures the fundamental right of every citizen to a clean and healthy environment. The government first brought the Environment Protection Act in 1997 and introduced a policy for controlling industrial emissions to improve air quality. This act was amended in 2019.

In the ‘Collection of Environmental Standards and Related Information’ published by the Ministry of Forests, there are six standards regarding air quality and smoke. However, most of those standards remain limited on paper only.

Senior Advocate Padam Bahadur Shrestha, who has been advocating against air pollution, illegal mining, and deforestation, says, “There are many laws and standards to control air pollution, but they are not being implemented. Air pollution occurs across the country, but the responsibility is given only to the Department of Environment.”

The Department of Environment should show activity in implementing the acts, laws, and standards established to maintain clean air by measuring pollution. However, the department has done very little work to improve air quality.

“No results-oriented work was done to control air pollution. Even a Supreme Court verdict to control air pollution has not been implemented,” said Senior Advocate Shrestha.

Auditor General Tanka Mani Sharma Dangal submitting the 57th Annual Report of 2020 to the then President Bidya Devi Bhandari on July 15, 2020. Photo Courtesy: Office of the Auditor General

The ‘Air Quality Management Action Plan for Kathmandu Valley,’ passed by the Council of Ministers on February 24, 2020, with the objective of improving Kathmandu’s air quality, aimed to implement ‘Euro 4’ standards to reduce vehicle emissions within one year. However, that too was not implemented. Six years later, the Ministry of Forests issued the ‘Vehicle Emission Standard, 2025.’ In it, ‘Euro 6’ standards are specified for four-wheelers across the country, and ‘Euro 5’ standards for two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and light four-wheeler small vehicles.

Although the government introduced a policy to give a green sticker to those who pass vehicle pollution tests and meet the specified standards, it has not been effective.

The reality of regulation is a mockery, says public health expert Dr Sharad Onta, who notes that vehicles officially certified with green stickers are frequently seen spewing hazardous black smoke throughout Kathmandu.

“We are witnessing a systemic failure where vehicles that have technically passed the pollution test and received green stickers are seen speeding away while leaving behind trails of dark smoke. If this is the state of four- to six-wheelers with set standards, the complete absence of regulations for two-wheelers makes the crisis even more desperate. This is a painful reality,” says Onta.

The government began testing three- and four-wheeler vehicles running in the Kathmandu Valley in the fiscal year 1999/2000. In the fiscal year 2002/03, diesel-powered three-wheelers were prohibited from running in the valley.

The 57th Annual Report of the Auditor General mentions that improvement in Kathmandu Valley’s air quality can be seen only when vehicle usage decreases. Air pollution in the Kathmandu Valley was controlled during the COVID-19 lockdown.

The policy to ban 20-year-old vehicles across the country within four months, by amending the Vehicle and Transport Management Regulations, 1996, and publishing it in the Gazette in 2017, is also almost a failure. The government itself does not have the infrastructure and technology for ‘scrapping’ old vehicles. After the vehicle owner pays the annual revenue, it only performs the task of removing old vehicles from the records. After removal from records, owners sell them to scrap dealers. However, owners drive expired vehicles without renewing them.

A dense shroud of haze blankets the Kathmandu skyline at 10:30 AM during the second last week of October. Photo: Bidhya Rai/Nepal News

“The government regulation, which is of an evasive nature, has made it easy for old vehicle drivers to act arbitrarily,” Senior Advocate Shrestha further added.

According to the Department of Transport Management, the number of public vehicles that have completed 20 years until the last fiscal year is 20,500, private vehicles 55,000, and government vehicles around 6,000.

To reduce pollution from smoke emitted by brickkilns, the ‘Standards Regarding Smoke Emission and Chimney Height from Brick Industries’ was introduced in the fiscal year 2017/18, setting a maximum limit for the amount of dust particles emitted from chimneys. In the Kathmandu Valley, brickkiln industries come into operation usually during the winter season.

According to environmentalist Tuladhar, since most brickkilns are allowed to operate near settlements, the implementation of the safety standards does not seem to exist.

Most provisions for air quality improvement have become useless. Therefore, toxic air has not been controlled but has gotten worse. For example, after air pollution became excessive in 2021, the government closed schools for four days. At that time, Kathmandu’s air quality reached 470 AQI.

According to the US Embassy’s air measurement station, Kathmandu’s AQI crossed 600 on January 4, 2021. The air quality monitoring station under the Department of Environment also showed the AQI was above 400. Nepal has repeatedly faced such extreme risky situations every winter.

Winter smog chokes the streets of Kathmandu, severely reducing visibility as stagnant air traps toxic pollutants. Photo: Nepal News

The government has not even been able to establish a sufficient number of air quality monitoring stations as needed. The 62nd Annual Report 2025 of the Auditor General points out that while the Ministry of Forests and Environment set a goal to establish 47 air quality measurement stations in the fiscal year 2023/24, they only established 30.

The air quality monitoring stations that are established are also centered in Kathmandu and cities. Nepal began establishing air quality monitoring stations in 2002. At that time, at least six measurement stations were established. While the Department of Environment increased the number of monitoring stations to 30 in the last decade, some seven are in the Kathmandu Valley, and about half of those are broken and cannot be operated.

Air monitoring method

Air pollution is checked using scientific instruments to measure the amounts of microparticles or liquid droplets and gas in the air. The result is measured by the Air Quality Index (AQI). AQI is a mixture of the amounts of particles smaller than 10 microns (Particulate Matter 10) and 2.5 microns (Particulate Matter 2.5), carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and ozone in the air. Such particles are emitted directly from different organic and nonorganic sources, while others are generated by chemical reactions while floating in the atmosphere.

Particulate matter is a fine particle. These particles are 10 times smaller than the width of a hair. These are harmful to human health. Particulate Matter 2.5 are very tiny particles that can only be seen using a microscope. These particles are emitted from smoke from vehicles, industries, factories, and especially from brickkilns, and from burning agricultural residue like wood, bonfires, coal, dung cakes, and hay, and from forest fires. When breathing, there is a risk of these particles entering deep into the lungs and even reaching the blood.

Smoke saturates a kitchen in Hatuwagadhi, Bhojpur, capturing the hazardous reality of indoor air pollution in rural households. Photo: Bidhya Rai

“Serious health problems like lung cancer, heart disease, and brain stroke occur from breathing polluted air. Particulate Matter 2.5 is more dangerous compared to Particulate Matter 10 because Particulate Matter 10 reaches up to our nasal passage, but Particulate Matter 2.5 goes inside the body without being filtered,” said air quality expert Rejina Maskey Byanju.

The Department of Environment has categorized the Air Quality Index (AQI) into seven levels. The department has classified AQI limited up to 50 points as healthy, from 51 to 100 as moderate, from 101 to 150 as unhealthy for sensitive groups, from 151 to 200 as unhealthy, from 201 to 300 as very unhealthy, from 301 to 400 as hazardous, and from 401 to 500 as very hazardous.

The department measures the AQI in one, eight, and 24 hours. Crossing 300 points in AQI is considered a terrifying state of air quality. The department’s data show that in Nepal, the AQI crosses 300 points for about five months every year.