KATHMANDU: Walking amid the Saturday afternoon bustle, it hardly feels like you’re strolling through a town that carries a 2,000-year-old tradition.

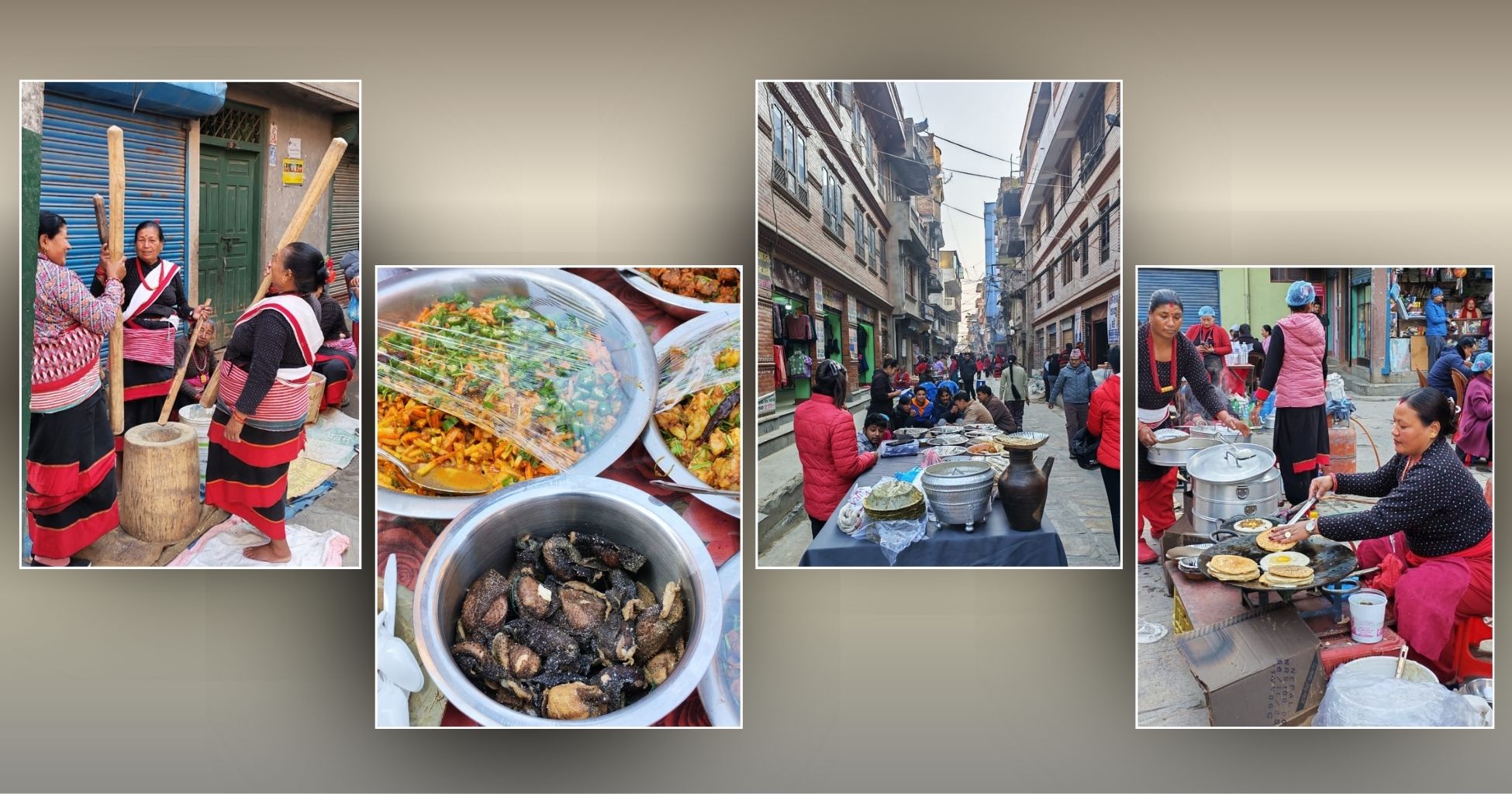

On this road of the town of Tokha – continuously inhabited since the Lichchhavi era, as inscriptions attest – vehicles are banned on Saturdays; everyone walks on foot. Rows of food stalls line the street. The smiles spread across the faces of girls dressed in haku patasi seem to invite guests – please come, eat at our shop.

There is no artificiality in those smiles, because they are not businesswomen. Here, all the women who cook and sell food are either homemakers, college-going girls, farmers, or women busy with other work on other days of the week. All these women are bound by a single purpose: to preserve their food. To preserve our indigenous flavors.

Tokha is famous for chaku. The Newari (Nepal Bhasa) word tu:khya, from which Tokha is believed to have evolved over time, is linked to sugarcane (ukhu) and its fields required to make chaku.

Those who recount legends say that tu:khy gradually became Tokha. Historians, however, say Tokha was a city even before the Lichchhavis arrived in Kathmandu. Since inscriptions use the indigenous word tilmak – not derived from Sanskrit – for canal (kulo), historians argue that this town dates back to the Kirat period or carries a tradition that is at least 2,000 years old, or perhaps was a garrison even earlier.

But nowhere in those historical records is there mention of the flavors cooked by mothers. This unwritten history – the tradition of our tastes – has been passed down by mothers. From mothers to daughters and daughters-in-law, and from them to granddaughters, just like the melody of folk songs, Tokha’s food tradition has flowed from one generation to the next.

Mothers must have preserved sa:pu mhicha as a dish that must be served to a daughter and son-in-law visiting for the first time.

Who would think, while putting hot sa:pu mhicha into the mouth, pulling the thread and chewing as the bone marrow scalds the tongue and palate, why that pouch inside the stomach didn’t spoil even without refrigeration? Deepika Shrestha and Kavita Maharjan have researched and even published an article in the Journal of Sustainable Development and Peace explaining that ginger plays a crucial role in preventing sa:pu mhicha from spoiling. According to them, the use of ginger not only makes the dish tasty but also hygienic.

Moreover, this indigenous knowledge and practice of using ginger controls microbial growth in the honeycomb stomach and allows sa:pu mhicha – made by stuffing bone marrow into a pouch of buffalo’s honeycomb stomach, tied with thread and boiled/fried—to be stored for a longer time.

It is such indigenous knowledge, now fading into obscurity, that has sustained Tokha’s culinary art. But that culinary art – knowledge accumulated over thousands of years – began to face the danger of disappearing. “That’s when the snack festival was started,” says Ganeshman Shrestha, chairperson of the Tokha Cultural Protected Area Development Committee. Active through many political upheavals in history, Tokha gradually became marginalized and moved forward as a society of agriculture and small trade. Ganeshman says, “We didn’t even know how to do business. We were extremely shy.

We felt embarrassed even to sell excess vegetables from our fields. Tokha residents feared society would mock them, saying, ‘They’ve come to the point of surviving by selling field greens.’”

People active in Newa guthi felt they had to work to preserve Tokha’s history, language, culture, and traditions. A seven-member team was formed and got to work. At that time, they realized that a historic settlement cannot be preserved without self-reliance.

It was precisely for self-reliance that the concept of the snack festival was moved forward, Ganeshman Shrestha explains.

Today, Tokha’s culinary art is presented to the wider Nepali public every Saturday at the snack festival held in Tokha. Whether you eat samay baji – a combination of beaten rice, chhoila, soybeans, black-eyed peas, garlic, ginger, greens, potatoes, and pickles – or just chhoila and beaten rice; whether you enjoy chatamari or wa (nowadays often called bara – lentil pancakes: mu wa (black gram bara), may wa (mung bean bara)), the taste that reaches your tongue carries the touch of a tradition that has endured for two thousand years.

If you want an even more thrilling journey for your palate, you can also taste khwāgwā mya, kachila, or janla. If you feel like something a bit soupy, there are mikwa (fenugreek) curry, potato and bamboo shoot dishes, and many other vegetables. And if you want an intoxicating drink, there is homemade thwo (rice beer) or ayla (liquor) from Tokha.

“We have stopped selling sealed liquor and beer,” says Ganeshman Shrestha, chairperson of the committee. The number of visitors to the Tokha festival is growing. Earlier, juju dhau was brought from Bhaktapur to sell. Now, milk is brought from Jhor and even farther from Nuwakot, and Tokha’s own juju dhau is prepared locally.

At first, Chairperson Ganeshman Shrestha’s team tried to run the snack festival by mobilizing snack hotels, but they didn’t want to take that level of risk. Then a gathering of local residents was organized, sisters came forward, groups were formed, menus were prepared, prices were fixed, and the snack festival began in November 2024.

“In summer, samay baji and thwo sell; in winter, wa and yomari. There’s a mutual agreement to run everything naturally. We all agreed not to add any chemicals even while making alcohol,” says Ganeshman Shrestha. “This is run with a community spirit. Through food, we are preserving culture. If chhoila runs out at one stall, they don’t tell the guest it’s unavailable – they bring it on loan from another stall and serve it anyway. For us, it’s not customers who come, it’s guests. And we treat them accordingly.”

At the snack festival, mothers dressed in haku patasi traditionally pound beaten rice. Visitors take photos of the mothers as souvenirs; some even step forward themselves, grab the mortar, and start pounding the rice. The festival hasn’t just shared food, it has connected tradition with modernity.

“Every week, 500 rupees is collected from each stall. That money is used for cleaning. The area is cleaned once before the festival begins and once again after it ends. Snacks and transportation expenses are also arranged for the scout volunteers,” says Ganeshman Shrestha. “A woman participating in the Tokha festival earns between 1,500 to 3,000 rupees in a week. Income from selling surplus spices, turmeric, and vegetables is additional.”

There are many plans – and many challenges. The noise and vibrations from large trucks and buses coming from the Nuwakot side must be controlled to protect this archaeological city. Yet some people are unhappy even with the road being closed for just 300–400 meters once a week during the snack festival.

“For the snack festival, we have 324 sisters. Right now, it’s run in rotation – 150 women manage the festival one week, another group the next. If even more guests come with love and support, we can mobilize all 324 sisters and add more stalls,” says Ganeshman Shrestha. “Our next plan is music. We want to pass down the melodies and rhythms of the songs sung by mothers. For that, we aim to organize musical programs bringing mothers and grandchildren together.”

Soon, perhaps, to the tunes of Tokha’s indigenous cultural instruments, people will be able to savor Newari dishes—and become part of the campaign to preserve culture.