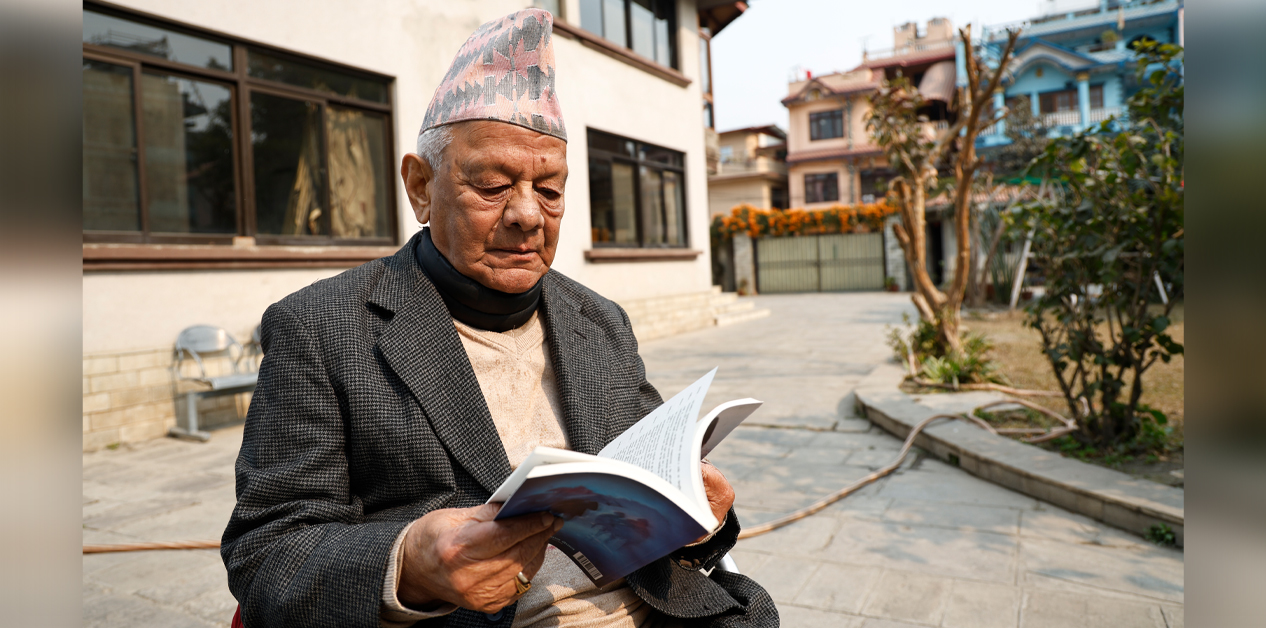

Well into his eighties and despite physical frailty setting in, Lokendra Bahadur Chand’s literary vitality is something many would envy

He will turn 86 this coming February. Back and knee problems have limited his mobility. His eyesight has weakened, and his spectacles have grown thicker. Yet his daily routine remains unchanged.

He wakes up at six every morning. He does not drink tea until he has completed his daily prayers and yoga. With the cold having sharply intensified in Kathmandu these days, he steps out of his room only around 10 a.m. to take a short walk in the courtyard.

Four-time prime minister Lokendra Bahadur Chand may appear physically weakened by advancing age, but his intellectual energy has not waned. During his years of active politics, he carried a lingering regret of not being able to devote time to literature. Having now stepped away from political life, he is fulfilling those unfinished desires, writing and rewriting with renewed dedication.

Doctors have advised him not to sleep after the morning meal. So, after his morning meal, he spends about two hours reading and writing. They have also cautioned him against straining his eyes too much. But his mind does not obey. His love for literature makes him forget the constraints imposed by age.

At present, he is revising his earlier works. Poetry collections such as Sandhyawali, written and published in haste during his busy political years, are now being carefully polished. His short story collection Pahunaghar (2011), published during the transition period following the Maoist conflict, is being translated into English, with help from his grandchildren. He has also completed a draft of his autobiography, which he is now updating with the assistance of his eldest son, Jayant.

“Only now have I truly found time after politics. I move around less, but I spend two hours every day actively rewriting,” Chand shared during a recent afternoon conversation.

Earlier, he lived at his home in Manohara Phant, Jadibuti, Kathmandu. With worsening back and knee problems, he now resides at his younger son Arun’s home in Kaushaltar, Bhaktapur.

His immersion in the world of literature is so deep that his thoughts and worries revolve entirely around it. He speaks of the loss of his old books with the pain of a parent who has lost children. “When I moved here, I packed my old books in a bundle, but they were never found. Until recently, I didn’t even have copies of my own works. Only after requesting Sajha Prakashan, well-wishers, and publishers did I manage to get three or four copies,” he says.

He has published half a dozen short story collections and has also written a novel. He wrote poetry in both Hindi and Nepali. Born on 3 Falgun 1996 BS (15 February 1940) in the remote village of Kurukuti in Baitadi district, far-western Nepal, his very first poem was written in Hindi.

At the time, Pithoragarh in India was the center of education for people from the far west. Chand was studying in Grade 6 there when he wrote a poem praising a flower. Impressed by the emotions expressed, his teacher, Banshidhar Bhatt, taught him how to fit the poem into proper meter.

Classes in Pithoragarh began around mid-July, but Chand enrolled only after the Dashain holidays. To help him catch up, the school principal arranged a special teacher – Bhatt himself, a poet – whose encouragement pushed Chand toward poetry.

“I was around 11 or 12 when I wrote my first poem in Hindi. Perhaps recognizing my ability, my teacher motivated me. I wrote about 75 poems in Hindi,” he recalls with joy. His Hindi poetry collection Indradhanush won the Dr Krishnachandra Mishra Hindi Award.

About three years later, he began writing in Nepali. In those days, far-western Nepal suffered from severe educational deprivation. Nepali curriculum barely went beyond basic alphabets. Apart from a few songs and poems by MBB Shah (King Mahendra’s literary name) broadcast on Radio Nepal, he had little exposure to Nepali literature. “Forget reading Nepali literature – people would answer ‘Jawaharlal Nehru’ when asked who Nepal’s prime minister was,” he recalls.

After 2015 BS, however, he immersed himself in Nepali literature when he enrolled at Tri-Chandra College in Kathmandu for certificate-level studies. He was captivated by the poetry of Laxmi Prasad Devkota, read stories by Pushkar Shamsher Rana, Guru Prasad Mainali, and Bhawani Bhikshu, and was drawn to the lyrical beauty of Madhav Prasad Ghimire. “I read as many books as I could in Kathmandu. It elevated my consciousness,” he says.

He soon moved from being just a reader to a writer, penning stories and poems after returning home from Kathmandu.

Literature had no strong lineage in his family, but his father, Mahabir Chand, recited Chandi paath every morning in perfect Anushtup meter and was skilled in playing the sitar. Growing up listening to sitar melodies and sacred chants nurtured Chand’s literary sensibility. He was also fascinated by the recited verses at village rituals. His father even arranged a music teacher at home, which is why Chand still plays the harmonium well today.

“Though there wasn’t a literary environment at home, my father’s sitar and Chandi verses must have nudged me toward writing,” he says. “Before poetry, I was drawn to music.”

He began writing short stories around 2020/21 BS, more than six decades ago. “Reading Mainali, Pushkar Shamsher Rana, and Bhawani Bhikshu shook my mind. That’s when I was drawn to fiction,” he says. His notable works include Hiunka Tanna (1985), Bisarjan (1998), Ratribhoj (2007), Pahunaghar (2011); satirical essays Barhaun Kheladi (1978) and Kursi (2011); the play Netako Sathi (2084); the novel Aparajita (2023); and poetry collections Aparichit (1994), Sandhyawali* (2001), and Timro Jhalak (2002).

After becoming a member of the Rastriya Panchayat in 1973 and returning to Kathmandu, both his reading horizon and writing pace expanded. “Books were available from everywhere – Nepali literature as well as works by Tolstoy, Chekhov, Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Somerset Maugham,” he recalls.

His essay collection Barhaun Kheladi gained wide acclaim, earning him the nickname “Twelfth Player.” The play Netako Sathi was staged from Kathmandu to district towns. Winning the Madan Puraskar in 1998 for Bisarjan established him not only among writers but also among the general public. “I was known as a writer before, but after the Madan Puraskar, I became known in almost every household,” he says.

Even while serving as Rastriya Panchayat chairman and later as prime minister, he continued writing. He jotted down emotions in his diary even while flying to official programs. “I had some time as chairman, but almost none as prime minister,” he says.

Queen Aishwarya, a literature enthusiast, once asked him during a Pokhara visit, “PM! You write poetry too? Recite something.” He obliged, though he no longer remembers which poem he recited.

Beyond his own writing, Chand yearns for the advancement of Nepali literature as a whole. He once offered suggestions to then prime minister KP Sharma Oli for literary promotion, but the Gen-Z movement toppled the government. “The country is Gen-Z–dominated now, but no one is paying attention to literature,” he laments. “If no one else comes forward, the media must. Only then can Nepali literature establish its relevance.”

In the twilight of life, his wish is to leave behind a meaningful literary contribution. What that will be, he chooses not to reveal.

At 85, his youthful energy and devotion to literature deserve admiration. Indeed, what a twelfth player!