It feels like a vivid portrayal of a society wounded by armed insurgency and social inequality — that’s Kanchhi, Weena Pun’s debut novel

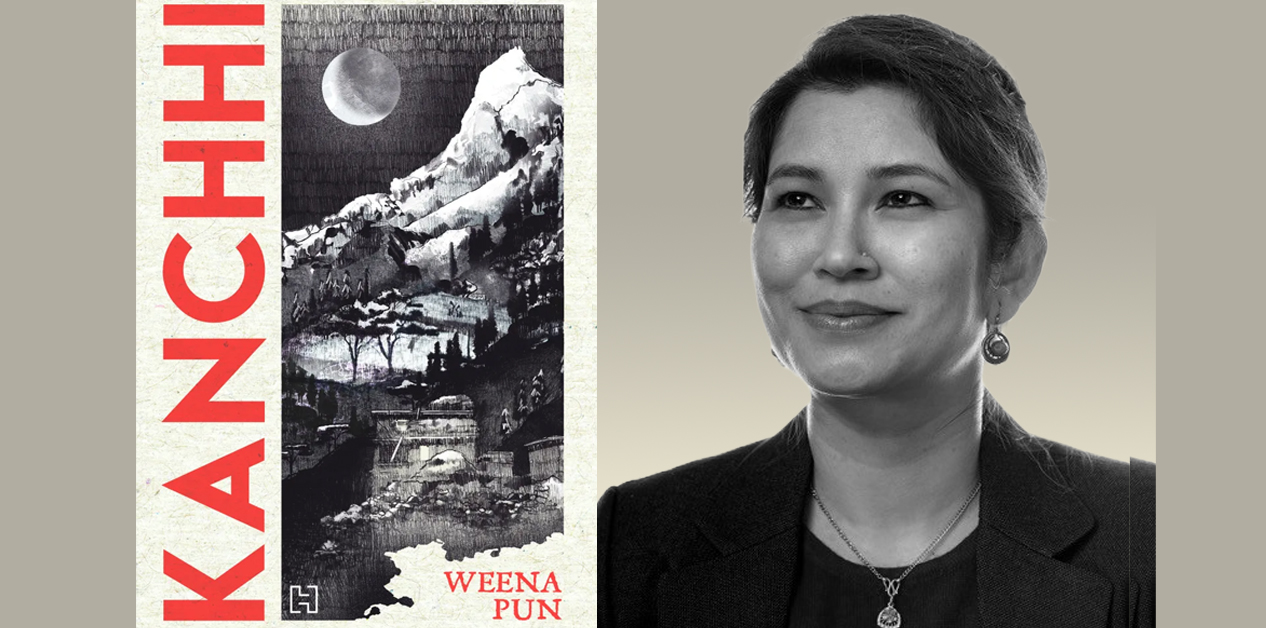

Weena Pun, whose name has often appeared in English language newspapers such as The Kathmandu Post and Nepali Times, published her first novel Kanchhi last year.

In Nepali society, the word kanchhi is very commonly used. It is also an affectionate way of addressing a young daughter. Weena has chosen this tender term as the title of her novel, centering it on a rebellious character who walks a difficult path. Kanchhi, the daughter of a single mother, lives in the fictional mountain village of Torikhola. Her father abandoned the family even before she was born. From a young age, she displays a fearless and defiant nature.

The opening line of the novel is: “Kanchhi was sixteen when she disappeared.” From this mysterious incident, the plot unfolds, revealing past events gradually. By intertwining the many dimensions of her mother Maiju’s life, the novel paints a broad and textured canvas.

Young Kanchhi is lively, daring, and courageous. When told she must go somewhere or perform a task, she does not accept restrictions. Whether it involves handling heavy loads or doing unpleasant chores, she proceeds without hesitation. Through Kanchhi’s actions, the novel directly challenges the prevailing social norms related to gender.

As she grows into adolescence, Kanchhi becomes curious about her changing body and develops new interests, guided by her teacher, Govinda. She reads magazines he provides, which mix sensational topics like sex and crime. She eagerly awaits each new issue. When she experiences menstruation, she only tells her mother after a year. When her mother questions her, she replies defiantly:

“Does everything have to be done according to your timing?” Through Kanchhi, Weena explores the spirit of rebellion.

Sexual desire naturally rises during adolescence. During this period, Kanchhi has a brief romantic liaison with Jhalanath, a Nepal Police officer, in her room. However, their relationship remains limited to sexual encounters. She refuses to be bound by marriage and domestic life, rejecting Jhalanath’s marriage proposal and stepping into an uncertain future.

Kanchhi has little ongoing support or companionship for her creative rebellion. The household and society provide no nurturing environment. While advice and admonitions abound, Kanchhi maintains self-respect. The support she receives from Jhalanath carries the scent of compassion, yet she cannot become a passive character in someone else’s narrative. As Arundhati Roy writes, “Power does not tell a woman’s steps straight; it confuses, provokes, and entangles her.” This insight applies to both Kanchhi and another character, Bimala.

The novel skillfully uses foreshadowing, a strong tool in narrative writing. The disappearance of Kanchhi at the very start sets a framework that later connects with Bimala’s story. Like Kanchhi, the independent Bimala follows her own desires, ignoring societal rules dominated by male authority, but ultimately faces social collapse and is forced into exile. Weena succeeds in using foreshadowing as an engaging storytelling device, portraying these events convincingly and intensely.

The mother-daughter relationship forms the heart of the novel. Maiju, a single mother, raises Kanchhi with dedication. The challenges of single parenthood — managing household responsibilities while protecting oneself from prying eyes — are vividly depicted. Many mothers around us live similar lives, often with little help and many obstacles. Kanchhi captures these social realities with remarkable depth, especially the gendered struggles within society. Despite the tension, the novel concludes with a tender reconciliation between mother and daughter, bound by mutual love.

Weena clarifies: “I grew up reading world literature continuously for a decade. Hence, this novel is my attempt to narrate the story of a Nepali girl from a village in Nepal in English.”

Weena currently lives in the United States and has experienced diaspora life firsthand. Yet, her novel does not incorporate the outside world; it remains firmly rooted in Nepali geography and context. The plot naturally flows through the environment she knows, depicting local traditions, events, festivals, and rituals in detail. The novel’s intricate descriptions of routine activities may feel dense to local readers but are likely to captivate international audiences.

Weena’s command of language is strong, and her prose flows smoothly. Local dialogue is used where appropriate, maintaining reading pace. For example, Kanchhi’s school friend Laxmi, who ran away to marry while still in school, says:

“No red, husband dead — that is, husband is gone; red is now forbidden.”

“She has got a horn in her butt: there’s a horn on her cheek.”

These brief, striking dialogues add a distinctive flavor. Weena carefully incorporates local sayings, folk songs, and idioms, including translations for English readers. Kanchhi’s story is enriched with some poetry written by Weena herself, creating a delightful rhythm and aesthetic continuity. Her characters reflect real villagers and ordinary people. The naming of characters feels entirely authentic. Although the society is predominantly Magar and Gurung, other ethnicities coexist peacefully. The rigid social structures of the 1950s subtly appear throughout the novel.

Weena also draws on the stimulating essays of Italian author Italo Calvino, particularly The Written World and the Unwritten World, which advocates engaging all five senses in storytelling. She vividly balances imagery to appeal to hearing, sight, taste, touch, and smell, ensuring readers remain immersed. The sounds of flowing streams, the rustling of wind, and the sweet chirping of birds create an almost musical experience.

The novel strongly reflects the contemporary conflict in Nepal, situating its narrative within the Maoist war and social turmoil. While many war-themed stories have been written in Nepal, Kanchhi stands out for embedding the conflict within its cultural and social milieu rather than presenting a flat political narrative. Instead, it offers a coherent depiction of a society wounded by armed conflict and social discrimination.