Flawed CIAA prosecutions erode the dignity of civil servants while inflicting significant financial and operational losses on the government

KATHMANDU: The Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) on May 15, 2025, filed a case in the Telecommunication Traffic Monitoring and Fraud Control System (TERAMOCS) purchase case against eight employees, including former Communications Minister Mohan Bahadur Basnet and Nepal Telecommunications Authority Chairman Digambar Jha. After the case, the daily work of the telecommunications authority became affected. This legal matter is currently pending before the Special Court.

On March 28, 2024, the CIAA filed a case against 19 people of the Telecommunications Authority and a contractor company on the charge of corruption in the purchase of equipment and consulting services to install the Mobile Device Management System (MDMS). The Special Court found the then two chairmen of the Authority and the contractor company guilty and acquitted all others.

After the CIAA registers a corruption case, all employees fall under suspension until the decision is made. However, most of them receive acquittal from the Special Court and Supreme Courts due to lack of evidence. Prohibiting accused employees from working until their cases are resolved not only cripples administrative efficiency but also traps individuals in years of legal limbo. The state ultimately bears a twofold burden; it loses years of productive labor and is later forced to settle significant financial claims for salaries and benefits once these employees are cleared of charges.

Why is this happening? Many attribute it to the mass filing of collective lawsuits.

CIAA Office. Photo: Bikram Rai/ Nepal News

Former Senior Director of the Telecommunications Authority Anand Raj Khanal says the government is bearing great loss because the CIAA files cases in bulk. The CIAA had filed a case against Khanal as well in the MDMS case. He, along with 12 others, received acquittal from the Special Court.

“When administrative staff who merely initiate a file face the same staggering fines as high-ranking chiefs, institutional morale vanishes. This blanket prosecution ensures that even those acquitted return to a culture of fear, where no official dares to sign a document or move a file forward,” said Khanal.

In criminal law, the burden of proof is on the plaintiff. However, in most, it is seen that corruption cases are registered without sufficient evidence.

Khanal notes that legal battles impose more than financial and mental pressure on employees, often straining family relationships to the breaking point.

“Legal actions are now targeting conduct that is not even criminalized by law. For instance, making a purchase before a procurement master plan is finalized is being labeled a corrupt act, even though it is a procedural matter rather than a crime. This haphazard prosecution, especially against international firms, is leaving critical national projects in a state of total disarray,” Khanal further added.

Two years after retiring due to the age limit, the CIAA filed a case in the Special Court on June 22, 2023, against former Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) Director Krishna Prasad Yadav, saying he earned a disproportionate amount of wealth. The corruption case caused stress, and Yadav had a very hard time gathering evidence against the charges. According to the law, whoever registers a case must gather the evidence. However, the CIAA only made charges against Yadav but could not present evidence in court within the time. On June 3, 2024, the Special Court delivered a not guilty verdict, acquitting Yadav.

“Being prosecuted two years into retirement made gathering evidence nearly impossible. Since we lacked modern digital systems and received salaries in cash, I had to manually search through physical archives to prove my innocence. This experience revealed the whimsical nature of how the CIAA files cases without a factual foundation,” Yadav added.

In September 2013, the CIAA launched a massive prosecution against 65 airport officials, including Non-Gazetted First Class Officer Sanjay Nepal, alleging visa fraud and financial irregularities. However, the legal basis for these charges proved fragile, as the Special Court acquitted 21 of those employees on May 17, 2016. This mass prosecution highlighted the devastating consequences of filing cases without individual scrutiny, as officials faced years of suspension and trauma before being cleared of all charges.

Ananda Raj Khanal notes that legal battles impose more than financial and mental pressure on employees, often straining family relationships to the breaking point.

“By the time of acquittal, the human cost was devastating: one colleague died from mental trauma, and two others were forced into retirement without their earned promotions. Who provides restitution for these lost lives and careers? The CIAA prioritizes the volume of lawsuits over legal merit, resulting in a dismal success rate because cases are built on unverified complaints rather than concrete evidence,” Sanjay Nepal contends.

CIAA Spokesperson Suresh Neupane, however, does not accept these charges above at all.

“We identify specific involvement by examining the signatures on every document; only those directly linked to the procurement process are prosecuted rather than the entire staff. Our investigating officers operate strictly within the legal mandate of the Act to ensure that charges are only brought against the individuals responsible,” said Suresh Neupane.

Senior Advocate Satish Krishna Kharel, however, considers this very investigation style as the CIAA’s weakness. He says a wrong tradition has started in the CIAA, where cases are filed against everyone, from the employees who “dipped their pen” or were marginally involved because their paper involvement was visible to the chief.

“The filing of cases against many retired secretaries involved in the construction of Pokhara International Airport is the latest example of this,” Kharel says.

According to Kharel, an investigator is a first-stage judge. If it can be distinguished who is guilty and who is not, 50 percent of cases end right there. Second, the judge is the government attorney who registers the case. If prosecution is done well, the overloaded court does not have to face an additional burden. The court gives the final decision, which decides the case based on the investigator and prosecution. Correct prosecution, facts, and evidence save an innocent person from the tag of a criminal case.

Kharel further adds that constitutional bodies should not be given the responsibility of stopping corruption at all. Pointing out the danger that quality manpower will not stay in the country if cases are filed against everyone who “dips their pen.” There should be an arrangement where there is supervision of prosecution, compensation for wrong prosecution, and the promotion of those who get acquittal due to the case should not be stopped. Filing of cases in the name of procedural errors should stop,” said Kharel.

In September 2013, the CIAA launched a massive prosecution against 65 airport officials, including Non-Gazetted First Class Officer Sanjay Nepal, alleging visa fraud and financial irregularities. However, the legal basis for these charges proved fragile, as the Special Court acquitted 21 of those employees on May 17, 2016.

Even though the Special Court’s procedure says a case must be settled within six months of registration, it is seen to take up to four years, so Kharel suggests that compensation should be given to those who receive acquittal by the time the verdict is out, and there should be an arrangement where their promotion is not affected after acquittal.

On April 4, 2024, saying corruption was committed in the wide-body aircraft purchase, a case was registered against 32 people, including former Minister Jeevan Bahadur Shahi, saying corruption of Rs 1.47 billion was committed. Board of Directors member Buddhisagar Lamichhane, who was involved in that, wrote a book called I Am Not a Corrupt Person. The Special Court found him and four others guilty. After the appeal petition was registered against the Special Court’s verdict, this case is currently under consideration in the Supreme Court.

Lamichhane has accused the CIAA of selective prosecution, saying he had no involvement in the corruption case. He has mentioned the reality of the wide-body purchase, the fallen morale of the bureaucracy due to wrong prosecution, and the effects on development and construction, and he has also mentioned questions that should be addressed while demanding accountability.

Looking at the data mentioned in the CIAA’s annual report, it is seen that on average, acquittal is received from the Special Court in at least 50 percent of cases. Looking at the data of corruption cases registered in the Special Court from the CIAA, a verdict has been made in 2,350 cases in 10 years. After not being satisfied with the Special Court’s verdict, the CIAA has appealed 1,061 cases in the Supreme Court. The CIAA is compelled to take half of the cases to the Supreme Court again. From the Supreme Court, corruption is established in only some cases by overturning (the district and special courts), and acquittal is given in some. The CIAA has not kept data on the success rate after the review of cases.

What is in the law?

In Section 25 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, there is a provision regarding investigation and inquiry. In that section, there is a provision that ‘if the investigation officer finds out through information, a source, or a complaint that any person has committed or is about to commit corruption, they shall conduct necessary inquiry and other necessary actions.’

Section 30 grants investigating officers broad discretionary powers, while Section 31 authorizes them to issue detention warrants. Upon judicial review of the evidence and inquiry progress, a case-hearing officer may grant custody for up to 30 days at a time, with a maximum cumulative detention period of six months.

Judicial ruling: Charges dismissed for lack of evidence

There are many examples of receiving acquittal because evidence was not sufficient when cases were filed in bulk, making investigation and prosecution weak. In a verdict made by the Special Court two weeks ago, it is mentioned that 11 people were given acquittal due to lack of evidence.

In Soru Rural Municipality-10 of Mugu district, the CIAA filed a 2024 lawsuit alleging that a Consumer Committee committed irregularities during a road project under the Chief Minister Employment Program. The prosecution claimed the road was shorter than agreed upon; however, the Special Court dismissed the charges on January 7, 2026. In its brief verdict, the court ruled that an offense cannot be established based on mere assumptions of overpayment without definitive physical measurements.

On January 6, at least seven people, including then Administrative Officer Pradeep Pariyar of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, received acquittal from the Special Court. When Pariyar was in Kathmandu Metropolitan City, a case was filed in bulk against seven people, including engineers, by connecting them with a tender call during sewer construction. The CIAA had demanded a fine amount and penalty of Rs 43.1 million each.

The bid was called, and the bid was submitted according to rules. Work started after an agreement was made at seven percent less than the cost estimate of Kathmandu Metropolitan. It is mentioned in the Special Court’s verdict that it could not be proved that loss or abuse was committed or caused by making an agreement with the bidder.

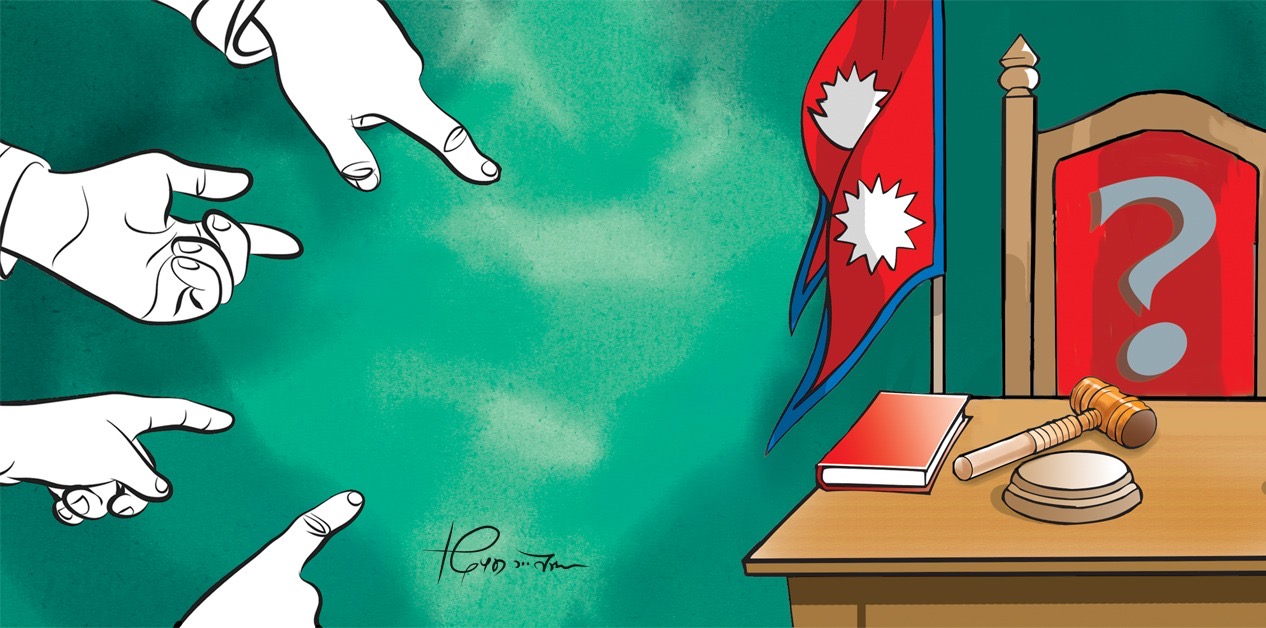

Supreme Court Nepal. File Photo.

‘The responsibility of submitting a charge sheet with a clearly specified claim lies with the prosecutor themselves,’ the Special Court has written repeatedly in verdicts. ‘By merely writing the name in the defendant section, saying persons seen to be associated with any offense without a claim are only defendants, the court cannot move forward to establish an offense and give punishment. If that is done, it will not only be against the principle of the rule of law but will also lead to judicial anarchy,’ the Special Court has said in the verdict regarding the Melamchi Water Supply project case.

In the same verdict, the court clarified that justice cannot be served by exceeding the specific charges and claims filed by the prosecutor. The ruling stated that if the prosecution appears uncertain or discouraged regarding the actual offense committed by the defendants, the court is compelled to halt proceedings against them. To hold such individuals responsible would violate the principles of natural justice. This was evident in the Melamchi Water Supply Project case, where, among the 15 individuals and two companies charged, 11 individuals were granted an acquittal.

The Supreme Court has established a definitive precedent: in serious offenses like corruption, guilt must be confirmed through direct and visible evidence. Simply leveling an accusation is insufficient because every charge must be substantiated by concrete proof. The ruling clarifies that the burden of proving a defendant’s offense rests entirely on the plaintiff. Any conviction based on mere assumption, suspicion, or guesswork rather than evidence violates the core principles of criminal justice, ensuring the accused receives the benefit of the doubt. This landmark precedent was set by the Supreme Court in the case of the Government of Nepal versus Devarshi Sapkota.