KATHMANDU: An outbreak of the deadly Nipah virus in India’s West Bengal has put Nepal on high alert, with health authorities stepping up screening at Tribhuvan International Airport, Kathmandu. Since December, two cases—both reportedly healthcare workers—have been confirmed in West Bengal, and nearly 200 contacts traced and tested negative. Nipah, which can spread from animals to humans, carries a mortality rate of 40 to 75 percent and has no vaccine or specific approved treatment, leaving Nepal’s public health system and travelers along the open border closely monitoring the situation.

Nipah causes flu-like symptoms that can escalate to fatal brain inflammation, or encephalitis, with case fatality rates reaching over 90 percent in some outbreaks. Making awareness and containment crucial for affected regions.

What is the Nipah virus?

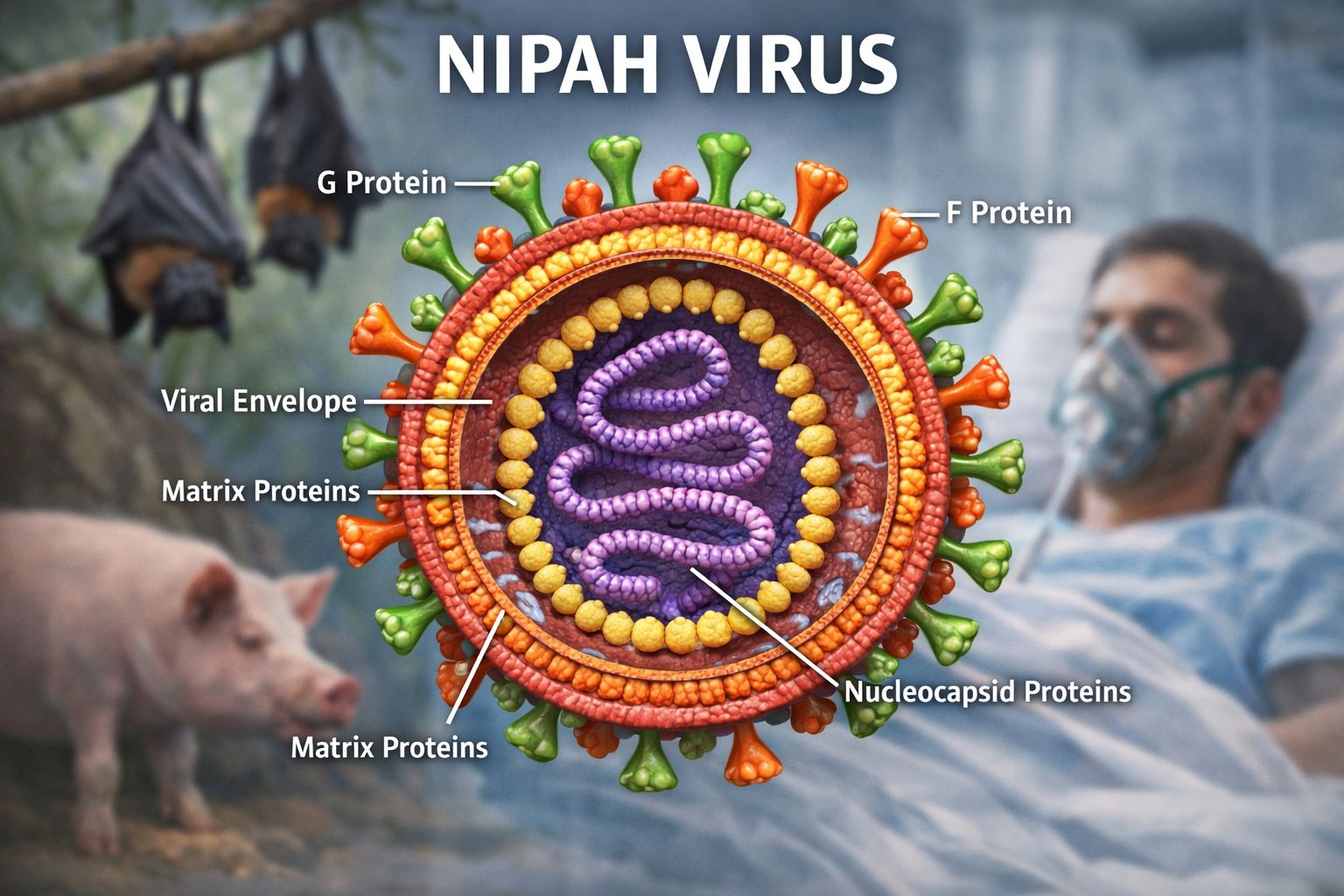

Nipah virus is a zoonotic virus that can spread from animals to humans and, in some cases, between people. It is transmitted through direct contact with infected animals, contaminated food, or close contact with infected individuals. First identified in 1999 among pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore, the virus is naturally carried by fruit bats of the Pteropus genus and can infect animals such as pigs, dogs, cats, goats, horses, and sheep. The World Health Organization lists Nipah among its top priority diseases because of its high fatality rate and potential to cause outbreaks.

What are the symptoms of Nipah virus infection?

People infected with the Nipah virus can experience a wide range of symptoms, and some may show no symptoms at all. Early signs often resemble a flu-like illness, including sudden-onset fever, headache, muscle pain, vomiting, and sore throat. In some cases, the illness can progress to drowsiness, confusion, altered consciousness, and pneumonia or other respiratory problems.

The most serious complication is encephalitis—inflammation of the brain—or meningitis, which typically develops 3 to 21 days after the initial illness and is the hallmark of severe Nipah infection. This stage is associated with a very high fatality rate. Overall, it is estimated that 40 to 75 percent of infected individuals die. Survivors may suffer long-term neurological problems, including persistent seizures and personality changes. In rare cases, the virus can reactivate months or even years later.

The incubation period generally ranges from 4 to 21 days, though longer periods have occasionally been reported. Currently, no approved drugs or vaccines are available to treat or prevent Nipah virus infection.

Why should we be worried about Nipah virus?

While Nipah virus is serious and potentially deadly, the risk to the general public remains low, especially outside affected areas. Experts are concerned because it is a zoonotic disease—it spreads from animals to humans—and human activity, like encroaching on wildlife habitats, can increase the risk. India has experienced almost annual outbreaks over the past two decades, which keeps neighboring countries like Nepal vigilant, but timely detection, monitoring, and public health measures help contain its spread.

How is Nipah virus diagnosed?

Diagnosing Nipah virus infection can be challenging because its early symptoms are nonspecific, often resembling a flu-like illness, and the infection may not be suspected initially. Accurate diagnosis also depends on the quality, type, and timing of clinical sample collection, as well as the time required to transport samples to the laboratory.

Laboratory confirmation is typically done through real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests on bodily fluids or by detecting antibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Other diagnostic methods include PCR assays and virus isolation via cell culture. In addition to laboratory tests, clinical history during both the acute and convalescent phases of the disease helps guide diagnosis and outbreak response.

How is the Nipah virus transmitted?

Nipah virus can spread to humans through direct contact with infected animals—such as fruit bats or pigs—or their bodily secretions. Many human infections have been linked to the consumption of fruits or fruit products contaminated with the saliva, urine, or droppings of infected fruit bats, particularly raw or partially fermented date palm sap, known locally as khejur juice when fresh and tari or khajuri tadi when fermented.

The virus can also spread from person to person through close physical contact or exposure to the body fluids of an infected individual. Such transmission has been documented in Bangladesh and India, especially among family members and caregivers. People with respiratory symptoms are considered to pose a higher risk of transmitting the virus.

What is the current status of the Nipah virus outbreak in West Bengal, India?

According to the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), two confirmed cases of Nipah virus disease have been reported in West Bengal since December 2025, both reportedly healthcare workers. In response, the Central Government, together with the Government of West Bengal, implemented comprehensive public health measures, including enhanced surveillance, laboratory testing, and field investigations, to contain the outbreak. A total of 196 contacts linked to the cases were identified, traced, monitored, and tested, all of whom were found to be asymptomatic and tested negative. No additional cases have been detected, and the situation remains under close monitoring by central and state health authorities.

How frequent are Nipah outbreaks in India?

This is the seventh documented Nipah outbreak in India and the third in West Bengal since 2001. Previous outbreaks in West Bengal occurred in Siliguri (2001) and Nadia (2007), both near the Bangladesh border, where near-annual Nipah outbreaks are reported. Other outbreaks have occurred in the southern state of Kerala.

What is the risk to neighboring countries?

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the risk of further spread from the recent Nipah virus outbreak in West Bengal, India to be low, noting that there is no evidence of increased human-to-human transmission. India has successfully contained previous outbreaks, and national and state health authorities are implementing coordinated public health measures.

The exact source of the infection is not fully understood, though fruit bats—known carriers of the virus—are present in parts of India and Bangladesh, including West Bengal. Public awareness about risk factors, such as consuming raw or partially fermented date palm sap, remains crucial.

This is the seventh documented Nipah outbreak in India and the third in West Bengal since 2001. Previous outbreaks occurred in Siliguri (2001) and Nadia (2007), while other outbreaks have been reported in Kerala. Bangladesh continues to experience near-annual outbreaks.

Neighboring countries are taking preventive action. Nepal has reported no cases, West Bengal does share a border with Nepal. Several Asian airports, including Nepal, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand have tightened passenger screening and health surveillance in response to the outbreak.

Nepal has also stepped up vigilance, initiating screening at Tribhuwan International Airport Kathmandu’s airport and at key land border crossings with India. Meanwhile, Taiwan is moving to classify Nipah virus as a Category 5 disease, a designation for emerging or rare infections that pose significant public health risks and require immediate reporting and special control measures.

Countries in the region are taking preventive measures. Nepal has reported no cases, but West Bengal does share a land border with Nepal, so the outbreak’s impact is possible in future.

Following the Nipah virus outbreak in West Bengal, India, airports across parts of Asia have tightened health surveillance and travel screening. Countries have implemented precautionary measures after two confirmed cases in West Bengal. In Thailand, the Ministry of Public Health has stepped up airport health screenings for passengers arriving from West Bengal, using monitoring techniques refined during the Covid-19 pandemic. These measures aim to detect potential cases early and prevent cross-border transmission.

How is Nipah virus treated?

There is no proven specific treatment for Nipah virus infection, and no licensed vaccine is currently available to prevent the disease. Care for patients is therefore limited to intensive supportive treatment, particularly for those with severe illness. This includes managing complications such as respiratory distress, neurological symptoms, and maintaining vital organ function.

Several experimental treatments are under development or in early clinical trials, including monoclonal antibodies, fusion inhibitors, and novel antiviral drugs.

The World Health Organization has designated Nipah virus as a priority epidemic threat, calling for urgent research and development, especially in vaccines and therapeutics, to better prepare for potential outbreaks.

Where is the Nipah virus found?

Nipah virus outbreaks in humans have been recorded only in South and South-East Asia, mostly in rural or semi-rural areas. The first recognised outbreak occurred in 1998–99 in Malaysia, primarily among pig farmers, and later spread to Singapore, killing more than 100 people and leading to the culling of about one million pigs.

Since 2001, Bangladesh has experienced the highest burden, with near-annual outbreaks and more than 100 deaths. The virus has also caused outbreaks in India, notably in West Bengal (2001 and 2007) and more recently in Kerala, which has emerged as a hotspot—reporting 19 cases (17 deaths) in 2018 and additional fatal cases in 2023. Other countries with reported human cases include the Philippines.

Although antibodies to Nipah virus have been found in fruit bats across Asia and parts of Africa, including Ghana and Madagascar, human outbreaks have not been documented outside South and South-East Asia.

What does ‘priority pathogen’ mean?

A priority pathogen is a virus or microbe that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers a serious threat because it has the potential to cause epidemics. Being classified as a priority pathogen means the virus—like Nipah—requires urgent research and development, including efforts to create vaccines and treatments for both humans and animals, to prevent or control future outbreaks.

How can the spread of Nipah virus be prevented?

Preventing Nipah virus infection relies on avoiding exposure to the virus, especially in areas where outbreaks have occurred. People should avoid contact with bats, their habitats, and sick animals. Consumption of raw or partially fermented date palm sap should be avoided, or the juice should be boiled before drinking. Fruits should be thoroughly washed with clean water, peeled before eating, and any fruit found on the ground or partially eaten by animals should be discarded.

Those handling sick animals or participating in slaughter or culling operations should wear protective clothing and gloves, and everyone should maintain good hand hygiene, particularly after caring for or visiting sick individuals. Close, unprotected contact with infected persons, including exposure to their blood or bodily fluids, should be strictly avoided.

The spread of the Nipah virus can be prevented through a combination of animal health control, personal protective behaviors, community awareness, and strict healthcare safety measures. In animals, particularly pigs, prevention focuses on maintaining high farm hygiene standards, regular cleaning and disinfection of animal shelters, isolating or quarantining suspected cases, and culling infected animals when necessary to stop outbreaks. Continuous surveillance of fruit bats, which are the natural reservoir of the virus, and livestock is essential to detect early warning signs and prevent transmission to humans.

Among humans, the risk of infection can be reduced by avoiding the consumption of raw or partially fermented date palm sap, which may be contaminated by bats, and by thoroughly washing, peeling, and properly storing fruits before eating. People who handle animals, especially sick ones, should use protective clothing, gloves, and masks, and practice frequent handwashing with soap and water. Close physical contact with infected individuals, including exposure to their bodily fluids, should be avoided to prevent person-to-person transmission.

In healthcare settings, preventing spread requires strict adherence to infection prevention and control measures. Healthcare workers must follow standard precautions, including contact and droplet precautions, and apply airborne precautions when required. Suspected or confirmed patients should be promptly isolated, and all medical equipment and surfaces should be properly disinfected. Laboratory samples must be collected, transported, and processed only by trained personnel in well-equipped laboratories using appropriate biosafety procedures.