Folk culture and traditional music serve as a vessel for human memory, preserving the many narratives of happiness and hardship shared across generations

KATHMANDU: As the nation navigates a new electoral chapter driven by the Gen Z protest, the legendary rock band ‘Cobweb’ has released a patriotic track titled ‘Jai Nepal.’ The song is a tribute to the nation’s diverse geography and heritage, referencing everything from the Karnali River to the Himalayan peaks. Most notably, Jai Nepal marks a historic shift for the band: after 30 years of defining Nepali rock, Cobweb has finally embraced folk instrumentation, blending traditional sounds with their iconic rock roots.

Cobweb is the band that made the rock genre popular in Nepal. It gave Nepali listeners a taste of a new style with the ‘heavy sound’ used in Western music. Established in 1993, the band has created more than 100 original songs. Among them, songs like Maryo Ni Maryo, Mercedes Benz, Preet Ko Nasha, Namaste, and Hodbaji are particularly liked. As of today’s date, listening to Cobweb is not just listening to music but also returning to memories of the 1990s.

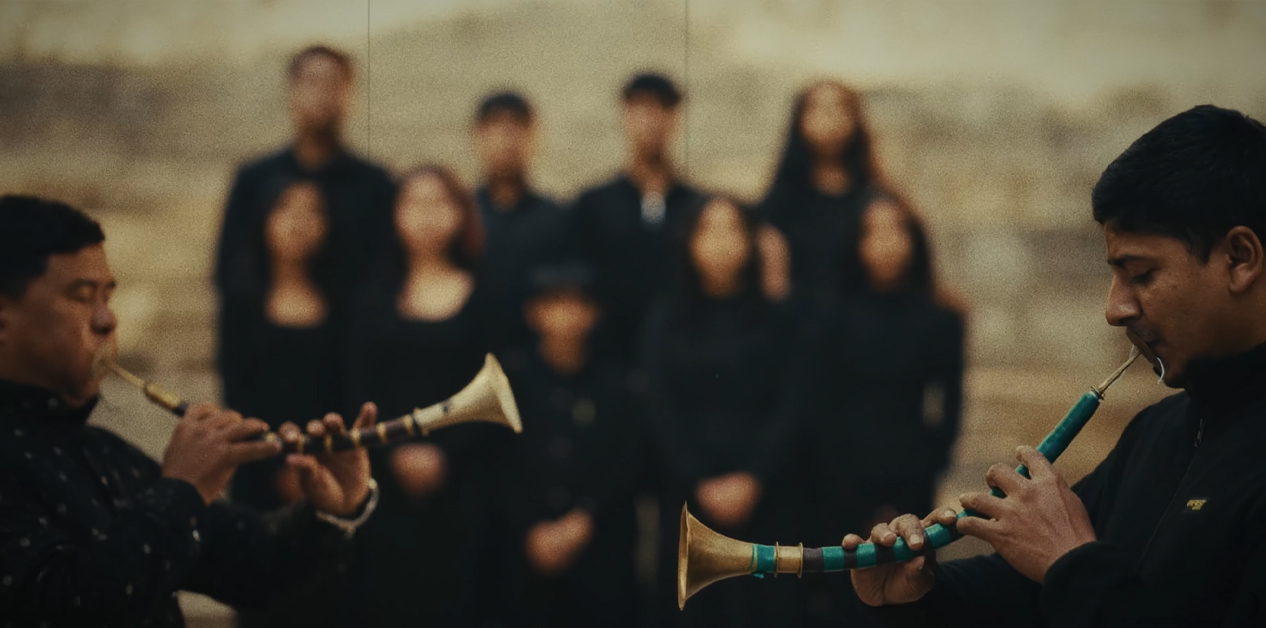

Even though they used folk instruments for the first time in their three-decade journey, Cobweb has not abandoned its signature tune in Jai Nepal. In this new song, where Western instruments like the guitar and cello are used, there is a beautiful combination of the music of instruments like the Bhushya (metallic cymbal that is part of the Newar musical style) and Dhime (Newari drum). Jai Nepal contains stories of the geography, culture, and pride of the Nepali race. It uses instruments ranging from the Nepali original Sahanaai (a type of trumpet horn) to the Bhushya.

Band founder and singer Divesh Mulmi said that he and other members of the band, who grew up in Patan, were attracted by the instruments used in the Machhindranath Jatra (The Chariot Festival of the God of Rain).

“In the rhythm section of this song, we used the same instruments used in the festival,” said Mulmi.

Bhushya and Dhime are instruments played collectively during festivals. These instruments, used to add energy to a crowd, create excitement in the human motion. The Nepali instruments used in Jai Nepal, composed in the Veer Rasa, are successful in generating that energy. A large group is also involved in the singing and playing in the song’s video.

Nilesh Joshi, a bass guitarist for the band Kutumba and also the band manager, says, “This song is not just an experiment; it is respect and love for our country, culture, and original instruments. I feel this is the kind of song we need in the current atmosphere of despair and doubt.”

Two years ago, on the occasion of the band completing three decades, a concert titled ‘Kutumba in Thirties’ was organized in Patan. It was at that program that Cobweb introduced folk into its rock identity. At that event, performing with Kutumba and giving the message of fusing folk with rock, Cobweb presented Jai Nepal to the audience for the first time.

Mulmi, who is also a guitarist, said that at that time, the sound of Kutumba hit us very hard.

“While making a song about the country, instead of doing something easy, in the process of doing something new, the idea came to use the festival instruments in the studio for the rhythm section,” said Mulmi.

Mulmi and Joshi say it took nine months to make this song, which involved about 50 artists, including three members of Kutumba.

Beyond the difficulty of managing everyone’s schedule, working with traditional festival instruments was a major hurdle,” Mulmi added. The beats differ across the three cities of the Valley and even within Patan itself. Because these rhythms are so localized, capturing them accurately for the record was not easy and demanded a great deal of patience and effort.

The founders of Cobweb grew up seeing the joy, enthusiasm, and excitement of the festivals, fairs, and cultural events of the Valley. However, it took three decades for this influence to appear in their music. It remains to be seen to what extent folk-traditional instruments or music will be used in subsequent songs. Mulmi says it is not possible to speak about this right now.

However, Joshi says, “It has been a lifelong dream to create a song that captures the joy and electric energy of our local festivals. Whether it happens sooner or later, we are committed to making that song a reality.”

Whenever that song arrives, it is certain that folk traditions and folk instruments will be used in it. Singer Deepak Bajracharya says that Cobweb’s upcoming journey will become more attractive due to its inclination toward folk instruments and culture.

“Collaboration between musicians who are experts in their genres, like Cobweb and Kutumba, is a very positive thing. This is exactly the kind of fusion we need,” Bajracharya added.

Singer Bajracharya himself was initially influenced by Latin American music. His songs, such as Ow Amira, Kali Kali, Maya Ko Dori Le, and Ritu, became famous. In 2014, under the album name Cream of Rhythm, he added the sounds of Nepali instruments to his old songs. Since then, he has been conscious of the use of Nepali musical instruments in his songs. When he released the song Man Magan in 2014 with a style different from before, his effort was successful. This song, which focused on traditional festivals, events, dances, and original instruments, not only became a hit but also increased the popularity of the Dhime instrument among the younger generation.

Regarding the reason for moving from Latin to folk, Bajracharya mentions the context of 2008. Around 2009, he reached America to perform a concert with his rhythm band. After a performance in front of some Nepali and foreign audiences at a program, two foreign listeners came backstage and asked him, “In your songs, only the language is yours; the music is ours. Don’t Nepalis have their own instruments?”

Bajracharya, who was born in the Newar community, which is rich in instruments, music, and dance, had not faced such a question in the 15 years he had been in music. He says, “That question became the turning point of my life. Works like Cream of Rhythm and Man Magan are attempts to find the answer to that question.”

After Man Magan was released, Deepak did not limit himself to Newari instruments. Myths and spiritual aspects within Newari culture also became subjects of his interest. The reflection of this interest can also be seen in his upcoming creation, Shwetkaal. In Shwetkaal, which is being prepared for release this month, he has attempted to depict the subject of positive and negative energy in the music video.

Bajracharya says he is waiting for a creation better and bigger than Man Magan. For this, after the musical instruments and culture of Kathmandu, he now wants to dive into the musical culture outside the Valley.

“Since Man Magan, Kathmandu’s music has dominated my work. Now, I have a plan to study the traditions and music of new places and societies,” Bajracharya says.

The faces of Nepali music: Both traditional and modern

In Nepal, many bands and solo artists like Rhythm and Cobweb are being attracted toward folk and traditional music through pop or rock music. It would not be wrong to say that this has been developing as a common trend in the last three decades. Among them, the journey of transformation of the Night band is also interesting.

Around 2001, Jason Kunwar and Niraj Shakya played heavy metal/death metal for the Maya band. Another member of the band, Bibhushan, would bring back information about folk tunes and original instruments every time he returned from outside Kathmandu for work.

“It was this that truly sparked our fascination with the traditional folk heritage of Nepal,” said Kunwar.

The result of this interest was that Maya turned into the Night band in 2006. Since then, this band has been dedicated to promoting folk-style songs and instruments from various regions of Nepal. In particular, Night, which has made a significant contribution to giving urban youth and foreigners a glimpse of Nepali folk traditions, has added sweetness to music by using instruments such as the Sarangi (a traditional, short-necked, bowed string instrument), Madal (hand drum), Nagara (kettledrum), Tyamko (small drum), Tungna (Himalayan lute), Piwancha (a traditional Nepali chordophone), Damaha (large kettledrum), Murali (flute), bamboo mallet, and leaves. The band’s songs, like Tuin, Putali, and Jhalka Raya Buka, are well-liked and pretty popular.

Abhaya & the Steam Engines, led by Abhaya Subba, who established herself with rock songs like Sakdina and Sapana Ra Kartabya, is also such a band. Modifying its old style, it has already made folk-based rock its identity. From Timrai Lagi, Nainital, and Hawahuri to the latest song, Hey Sailaa, a beautiful fusion of rock and folk.

Lochan Rijal, who entered music through pop singing, is a creator who became attracted to the formal study of folk music while being drawn toward rock. He completed a master’s in ethnomusicology from Kathmandu University and earned a PhD in the same subject from the University of Massachusetts in America. Devoted to bringing traditional instruments into modern use, he made the Arbajo (a Nepali four-string lute used as a rhythm instrument) famous.

During the time of the competitive market for pop or modern music, he had mixed two types of instruments, the Arbajo and Sarangi, in one place in the song titled Paurakhi. In Rijal songs like Sukha Dukha, Pailaharu, Chetana, and Samaj, he performed a new experiment by mixing the melodies of the Arbajo and Sarangi with instruments like the guitar, Nagara, and violin, which listeners also liked.

“To develop Nepali music, much creative work remains to be done by studying or researching musical traditions, refining them, and connecting them with the market. Fortunately, the listeners liked my work. However, the work I have done is only a small part,” said Rijal, who is active in teaching music at Kathmandu University.

Many things confirm that this inclination and attachment toward folk and traditional music is not a separate stream but has already been established as the mainstream. Nepathya, considered the most famous in Nepal, arrived at folk-pop-rock through pop-folk-pop. In the melodies of bands like Kandara and Mongolian Heart, folk style is always at the center.

At one time, famous bands like Doctor Pilot, Namaste, Deurali, Bro.-sis., and Gloomy Guys were popular because of their folk-pop style. Whether it is Karma’s Hukka Mero Dalle Dalle or Mukti and Revival’s Dalli Resham or Chaubandi Choli, folk features are found. Songs of 1974 AD such as Deurali, Chaubandi Choli, and Gurasai Fulyo Banaima also belong to this stream. The reason urban youth generations like the songs of Trishna Gurung and Bipul Chhetri is the fusion of folk style.

When tradition is presented in a modern style, it appears that listeners and viewers in villages, cities, and abroad have liked it equally. Recently, the popularity of the Kuma Sagar & The Khwopa bands is a strong example of this. Kuma and his group have added a new dimension to traditional Newari music by presenting Dafa Khala hymns in a modern style.

Such fusion is not limited only to folk-pop or rock. At one time, remixes of many songs like Jham Jham Eastcoat, Chyangba Hoi Chyangba, Hariyo Bhannu, and Kalkatte Kaiyo were also popular. When folk was mixed even in raps like Abhinas Ghising’s Hamro Gaule Jeevan and Nirnaya’s Din Pani Bityo, folk-rap took the form of a new genre. When Navneet Aditya Waiba sang the songs of her mother, Hira Waiba, the fact that the new generation liked them even more is also the attraction and charm of folk music.

Recently, after the grandson of Ramsharan Nepali released his song Yo Keti Kaha Ko Udaipurai Ko, it has come into further discussion.

It is a normal process for people to migrate from villages to cities and from small cities to large modern cities. However, in this process, a person perhaps gets stuck at the crossroads of modernity and tradition. People caught in such a crossroads probably like to sing and listen to tunes where the modern and traditional are mixed.

As the world shrinks due to technology, Nepali artists are also seen performing Nepali fusions of foreign music. Manish Gandharva and Tunna Bell Thapa released an instrumental cover of the song Despacito, the most viewed on YouTube, in which the melody of the Nepali Sarangi can also be heard. Under the name Skin and Bones, they have made covers of many Hindi and foreign songs using the melodies of the sarangi and guitar.

Fusion work is also happening in classical music as well. Gurukul Dhrupad, which Bishal Bhattarai is practicing with Japanese musician Inoue Sou, is also a form of fusion. Project Sarangi, led by Sarangi player Kiran Nepali, is promoting the Sarangi in Nepal and even abroad. Nepali has made Sarangi versions of everything from Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here to the Nepal Bhasha (Newari) song Maya Re Ratna, which are available on YouTube.

Arko Mukherjee singing the songs of Jhalakman Gandharva is also an affection for folk music. In the latest generation, bands like Ketaharu, Crazy Brothers, Gaule Bhai, and Baaja have earned fame by mixing folk into the pop or rock genres.

The ability to mix and merge into various genres is a characteristic of music. The relationship of Western classical music is tied to the church and rituals. Music that started from there was mixed with the music of African slaves and reached today’s jazz or modern music.

Due to the many creators active in the practice of understanding and explaining tradition and modernity, Nepali music is also evolving. Singer/researcher Rijal sees the possibility that such sequences and sub-sequences will contribute to building the cultural identity of Nepali music.

“Whether it is music or other fields, this is a time when Nepal and Nepalis are searching for their true identity,” said Rijal.

Previously, folk was confined to melody; in the last 10-15 years, the number of people using Nepali instruments appears to have increased. Singer Bajracharya says, “When I played the Dhime instrument in our band, people would stare in amazement. They would be shocked when something played in a festival was taken into the studio.” His experience is that many instruments played in Kathmandu’s festivals, such as Dhime, Damaha, and Khi, have already become popular.

Cobweb’s Joshi says that although there are many instruments among the Newar community of the Valley, the skill to learn them was not transferred to youth due to lack of interest.

“Fifteen years ago, there were hardly any spaces to play traditional instruments. Today, Jyapu Samaj and Guthis appear to be working to preserve these instruments by teaching them to children and even to women,” said Joshi.

The memories of people live within traditional instruments, folk tunes, and folk culture, containing many stories of sorrow and joy. Collective feelings and identity are also derived from within this. Due to these characteristics, folk music makes a significant contribution to the construction of a shared cultural identity. This is an identity that acts as a cultural boost pushing society forward.

Wherever Nepalis have reached, Nepali music and culture are spreading. Through technology, access has been directly reached among international listeners and viewers.

“Our ethnicity is the only foundation for presenting and marketing ourselves in the international arena. Our distinct identity lies in our authentic music, expressed through traditional songs, dances, and musical instruments,” says singer Bajracharya.