Defendants face economic, social, and mental impact for which there is no compensation if they are acquitted by courts

On 7 December 2025, a case was filed at the Special Court against 54 individuals, including Ram Kumar Shrestha, chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal, accusing them of corruption during the construction of Pokhara Regional International Airport. In the case filed by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), a claim has been made for compensation of Rs 8.36 billion per person, fines, and punishment.

The CIAA claims that the government paid Rs 24.58 billion to the construction company while building the airport through Chinese loan investment. However, when the total compensation amount claimed by the CIAA—accusing 54 individuals of misappropriating Rs 8 billion each—is added together, it reaches Rs 432 billion.

Even if the entire Rs 24.58 billion paid by the government is considered as the loss or damage borne by the state, the amount claimed by the CIAA appears abnormally excessive—more than 18 times higher. For a total alleged loss of Rs 24.58 billion attributed to 54 individuals, each individual has been assigned compensation exceeding Rs 8 billion. This case represents a clear example of how, due to the absence of standards for determining compensation, claims for damages or restitution are being made arbitrarily based on estimation.

There are numerous examples of cases in which the CIAA and the government side claim extraordinarily large compensation amounts during prosecution, but courts fail to uphold those amounts. Failure to establish the claimed compensation means the case brought before the court is weak or unsuccessful. On the other hand, such abnormal compensation claims impose economic, social, and mental harm on defendants. Even if the accused are acquitted by the court, there is no compensation for the damage they suffer, because there is no law governing compensation in such circumstances.

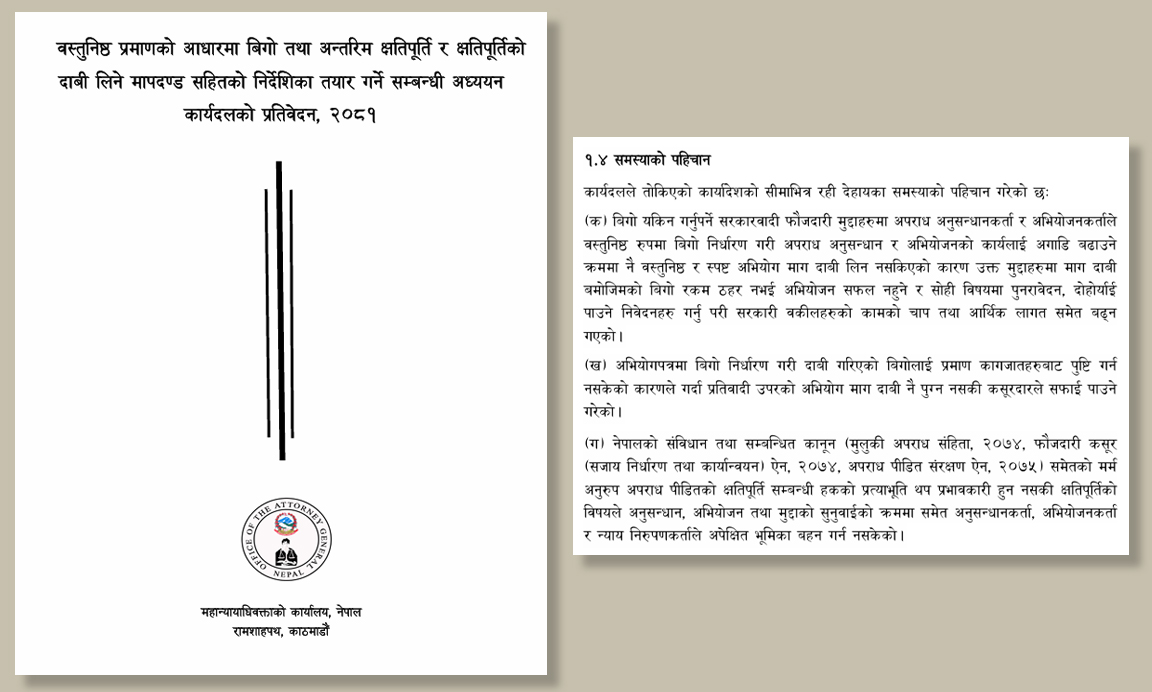

A study report by the Office of the Attorney General, the main constitutional body that provides legal advice to the government, has identified abnormal compensation claims as one of the reasons cases fail in court. The report states that criminal cases filed by the government fail because of improper methods of determining compensation. It notes that when large compensation amounts are claimed without due attention to facts and evidence, cases become weak.

To study cases with arbitrary compensation claims and related court verdicts, the Office of the Attorney General formed a nine-member task force in 2081 BS (2024/25) under the leadership of Deputy Attorney General Khemraj Gnyawali. The task force report found that cases registered in district courts, high courts, and the Special Court involving large and abnormal compensation amounts are extremely difficult to prove. As a result, in many large-compensation cases, the prosecutors’ claims of “billions of rupees in compensation” or “hundreds of millions in losses” have become merely a matter of public consumption.

There are also examples where cases upheld with large compensation amounts by lower courts fail to maintain those amounts when they reach the Supreme Court. In one precedent, the higher court upheld only one-fourth of the claimed compensation.

In a case registered on 11 June 2010 at the Kavrepalanchok District Court, the government accused Saraswati Baidya of revenue fraud for allegedly causing losses to the government by bypassing calls using 10 Nepal Telecom telephone numbers. Based on an assumption that the phones operated 24 hours a day, the government claimed compensation of Rs 8,451,544.

The district court and the then Patan Appellate Court upheld the same compensation and imposed compensation and fines on defendant Baidya. However, Baidya filed an appeal at the Supreme Court on 31 July 2013. Nine years later, when the Supreme Court delivered its verdict, it did not find the Patan court’s decision justified. It reduced the compensation to one-fourth of the amount set by the appellate court—only Rs 2,101,200. The full bench comprising then Acting Chief Justice Deepak Kumar Karki and Justices Kumar Regmi and Hari Prasad Phuyal delivered this verdict on 14 July 2022.

There is also an example of a case filed by the CIAA itself at the Special Court claiming Rs 100 million in compensation, where only Rs 10,000 was ultimately upheld. On 3 August 2022, a case was registered under the “Save the Daughter, Educate the Daughter” program involving bicycle procurement in Madhesh Province. The CIAA filed the case against then provincial secretary Yam Prasad Bhusal, Bhagwan Jha, and eight others, claiming Rs 103.3 million per person in compensation along with punishment. The Special Court sentenced Bhusal and Jha to three months’ imprisonment and a fine of Rs 10,000, stating that the prosecution failed to clearly present details of the actual loss incurred. In its verdict dated 25 January 2024, the court stated that the accusation was made without specifying the brand of bicycles purchased or mentioned in the contract.

When filing cases, the CIAA and the government side tend to assign equal compensation to all defendants collectively when there is more than one accused, instead of determining compensation based on the actual damage caused by each individual. However, in an old fraud case, the Supreme Court interpreted that when there are multiple offenders, compensation should be recovered according to the loss caused by each individual, and only if separate amounts cannot be identified should compensation be recovered equally (on a proportional basis).

In a verdict delivered on 14 June 2006, the court stated: “If there is only one offender, that person alone must bear the entire compensation. If there are multiple offenders, each must bear compensation equal to the amount they misappropriated, and if separate amounts cannot be established, then compensation must be recovered proportionately from all defendants.” In the case of Government of Nepal v. Indra Prasad Nepal, a joint bench of then Justices Badri Kumar Basnet and Tahir Ali Ansari stated: “If the offender is a single individual, the entire fine applies to that person alone; if there is more than one offender, it is clear and certain that the punishment shall be borne proportionately.”

In money laundering cases, the Supreme Court has ruled that entire banking transactions cannot automatically be treated as compensation. In Government of Nepal v. Krishna Basnet case, the Supreme Court stated in its verdict dated 9 September 2021: “A grossly determined compensation amount cannot be used to establish an offense.”

Senior Advocate Krishna Prasad Sapkota states that the method of determining compensation is not objective. According to him, in some cases involving loss to the state treasury, compensation is claimed without deducting the value of goods purchased or work already completed during development or construction. While it is appropriate to demand full compensation when payment has been made without any work being done (i.e., zero work), claiming total investment as compensation in cases where work has progressed is not objective.

“If no work has been done but payment has been made, then full compensation is justified,” he says. “In many cases, construction work has been completed and materials have already been purchased, but without distinguishing the degree of wrongdoing, the total investment is claimed as compensation. That is wrong.”

Since losses can be understood and demonstrated, Sapkota suggests that they must be established through detailed and meticulous investigation. He argues that making identical claims against all defendants is neither scientific nor objective. “There is no coordination between the degree of crime and the severity of punishment. Claiming the entire cost as compensation and talking about billions is merely a public stunt,” Sapkota says.

Decline in case success due to compensation (bigo)

According to the legal glossary, bigo means “the loss or damage suffered by the victim as a result of an offense; damage caused by a crime; money or property that an offender must pay; compensation, restitution, indemnity, or reimbursement payable for causing loss to someone.”

In any criminal case, the government files a case in court claiming compensation (bigo), fines, and punishment. While filing the case, compensation is claimed by including the goods or property that the accused is alleged to have misappropriated or caused damage to. The court delivers its verdict based on the evidence presented by the prosecution.

In the Nepali context, the issue of compensation is closely linked with economic crimes. In some economic offenses, the law determines the extent of punishment based on the amount of compensation. For example, in corruption and banking offenses, the amount of loss suffered by the victim is established as compensation and must be recovered for the victim. If the compensation determined by the court is not paid, there is a legal provision requiring the offender to compensate even by serving imprisonment.

However, cases have repeatedly weakened because compensation is not determined objectively and scientifically. A 2081 BS (2024/25) study report by the Office of the Attorney General on “Compensation and Interim Relief” states that in most cases, charges could not be fully upheld by the courts because the allegations were not objective. The report points out that in criminal cases, compensation amounts often fail to be upheld because they are not made objective and are instead determined based on estimation.

The report states: “Looking at the current status of criminal offenses involving compensation, it appears that in most cases the claimed compensation amount has not been upheld because the charge itself was not determined on an objective and scientific basis.”

Because prosecution has often failed precisely due to filing cases with excessively high compensation claims, the Office of the Attorney General has already proposed amendments to the law to make compensation determination objective. The report also notes that when cases are not upheld at the trial court or when either party (plaintiff or defendant) is dissatisfied, repeated appeals and re-filings increase the workload of government attorneys.

Section 9 of the Judicial Administration Act, 2016 provides that appeals may be filed in cases decided by the High Court as the court of first instance, cases involving imprisonment of ten years or more, cases involving imprisonment of three years or more, fines exceeding Rs 500,000, or compensation exceeding Rs 2.5 million. In government criminal cases decided by district and high courts, if any of these conditions exist, the Office of the Attorney General files an appeal at the Supreme Court.

According to the report, determining actual compensation is complex in offenses such as hundi (informal money transfer), cryptocurrency, and gambling because transactions are digital. Compensation is often determined based on all transactions rather than only those related to the offense. “There is no definite standard for depreciation of goods either. In cases such as revenue leakage and gold smuggling, compensation is often determined based on estimation without establishing the value of seized goods,” the report highlights.

On the one hand, the absence of evidence collection to substantiate compensation has created difficulties for victims seeking recovery through the courts. On the other hand, there is no calculation of the economic, social, and mental harm suffered by defendants.

Process of legal amendment

After criticism regarding the incorrect method of prosecuting compensation claims, proposals were made to amend criminal laws. Former Attorney General and senior advocate Ramesh Badal recalls that a task force was formed to study the issue because compensation was being imposed incorrectly in many cases.

“Because compensation appeared abnormal, efforts were made to amend the Act and proceed accordingly,” he says. “We were preparing to discuss the draft bill, seek suggestions, and submit it to Parliament through the Ministry of Law, but due to a shift in circumstances, it could not be introduced.” The law proposed for amendment would not have applied to old cases.

Following the dissolution of the House of Representatives after the Gen-Z revolt, the draft bill has remained shelved at the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. The draft bill states: “In the case of any property or goods, compensation shall be determined based on the current market value according to the purchase bill. However, compensation shall be determined after deducting depreciation based on the manner of use, condition, and quality of the goods.”

It also proposes that compensation should be determined based on the benefit obtained by the offender or the loss caused to the state.

Another senior advocate, Sapkota, states that in cooperative fraud, theft, and banking fraud cases, if Rs 100 million has been embezzled, equal compensation should not be claimed from all accused individuals.

“It must be examined who took how much loan, and the responsibility and role of each accused must be established,” he says. Based on his experience, many defendants are acquitted because the basic principles of prosecution are flawed, which also confuses the court.

“When claims are made vaguely—without clarifying the extent of involvement or the amount of embezzlement—the court grants acquittal. Then rumors spread that the court acquitted corruption cases. The general public never knows the real facts,” he says. “To control crime, special attention must be paid to investigation and evidence. Filing prosecutions in bulk and claiming compensation blindly is wrong.”

Legal provisions

Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees the right of victims to compensation as a fundamental right. Section 40 of the National Penal Code specifies types of punishment, including life imprisonment, imprisonment, fines, imprisonment and fines, compensation, imprisonment for failure to pay fines or compensation, and alternatives such as rehabilitation centers or community service.

There are provisions to establish and recover compensation for victims in corruption and banking offenses. In crimes such as theft and fraud, compensation is confiscated, and imprisonment is imposed if compensation is not paid, making it mandatory that compensation be precisely determined.

Compensation is not only related to punishment but is also linked to victims’ rights. It is not merely an individual right but also an economic matter.

Section 51 of the National Penal Code, under acts prejudicial to national interest, states: “If any amount has been transacted, in addition to the punishment under Subsection (4), the transacted amount shall also be confiscated.” Section 73 of the same code provides that in cases of damage or destruction of essential goods, fines and compensation equivalent to the loss must be recovered. Section 262 A (3) provides for confiscation of intangible or monetary assets earned or increased through any offense.

When determining compensation, the claimed amount must be equal to the value of the goods or the amount of loss. For example, if the market value of a stolen laptop is Rs 100,000, the compensation claimed must be the same amount.

In economic crimes, the extent of punishment is classified based on the amount of compensation. Section 15(10) of the Banking Offenses and Punishment Act, 2008 provides that if a person commits an offense and the compensation amount is determined, the offender shall be required to pay the compensation, a fine, and may be imprisoned for up to three months. If the compensation is up to Rs 5 million, imprisonment ranges from one to three years, and if the compensation exceeds Rs 500 million, regardless of how high it is, imprisonment ranges from seven to nine years—thus classifying imprisonment based on the compensation amount.

The case related to Pokhara International Airport, in which compensation of more than Rs 8.25 billion per person has been claimed, is currently under consideration at the Special Court. How much compensation the court ultimately determines in that case has become a significant judicial question.