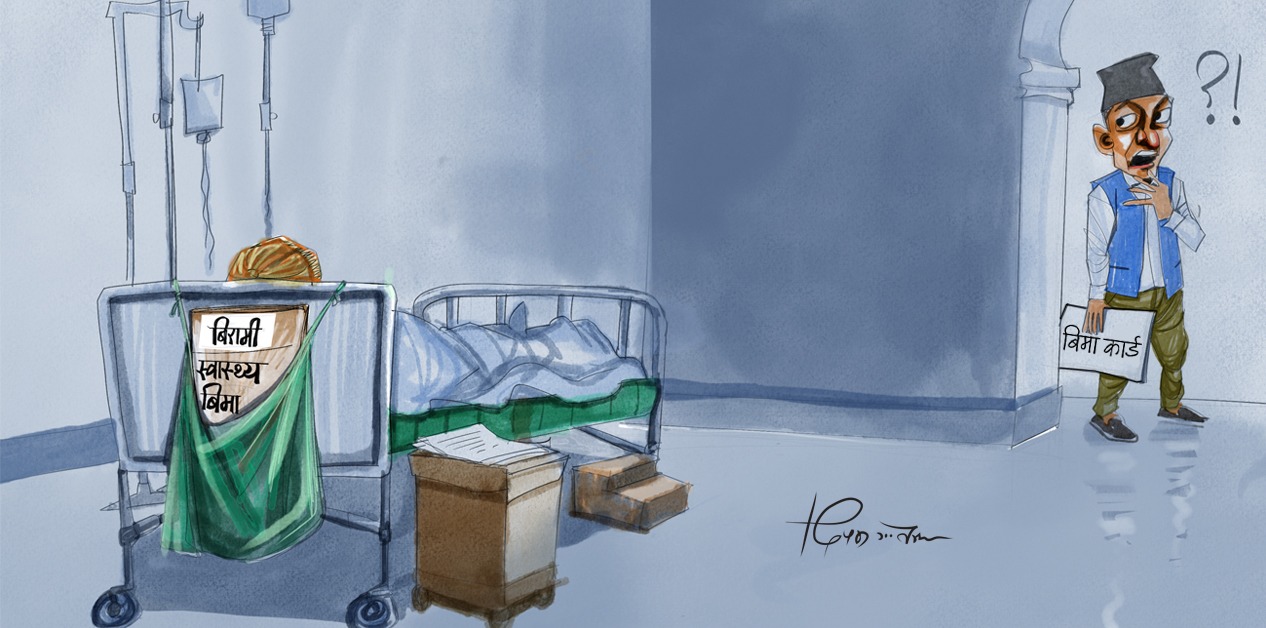

Failure to implement legal provisions deprives poor citizens of even basic treatment services

KATHMANDU: The health insurance program, launched with the objective of providing healthcare services to citizens, has itself fallen into a serious crisis. Hospitals that have provided treatment services to insured citizens have outstanding claims of Rs 12 billion, but the Health Insurance Board does not have the funds to pay these dues. As a result, the Board’s liabilities are increasing by around Rs 2.5 billion every month, pushing it deeper into crisis.

Citing non-payment, major hospitals have started suspending treatment services under the health insurance program. This has put an exemplary program, introduced mainly to provide affordable treatment to poor citizens, on the path to failure.

Nepal’s Constitution recognizes health as a fundamental right of citizens. It guarantees every citizen free basic health services from the state and ensures that no one shall be deprived of emergency healthcare. In line with this provision, the government launched the health insurance program in 2071 BS (2014/15) to ensure access to basic health services. Its core objective was to prevent citizens from having to sell land or property when they fall ill, with insurance bearing the financial burden of treatment.

The health insurance program has reached all local government units across Nepal’s 77 districts. Under this system, 510 health institutions—including public hospitals, community health institutions, and a limited number of private hospitals—are affiliated as service providers.

According to Board data, 30 percent of the total population (10.2 million people) are enrolled in health insurance. Among them, more than 50,000 citizens receive treatment services daily through insurance. For this, the Health Insurance Board spends over Rs 80 million per day. On paper, this appears to be an impressive achievement, but the question of sustainability remains extremely complex.

Among those enrolled, the number of active insured individuals is 6.97 million, representing 2.427 million households. Of these, 55 percent of households receive free treatment services, according to Health Insurance Board public health officer Bikesh Malla.

However, due to poor financial management, the insurance program—upon which millions of citizens depend for affordable healthcare—has fallen into deep crisis. The Board owes around Rs 12 billion to hospitals that have been providing treatment under the insurance scheme. Of the total claims submitted by 510 service-providing health institutions, only 46 percent has been paid. “Only 46 percent of the amount owed to each hospital has been paid. Whether government or private, payments have been made equally without discrimination,” says Malla.

Due to prolonged non-payment of dues, hospitals have begun halting insurance-based treatment services. Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital and Shahid Gangalal National Heart Center have already stopped providing services under health insurance. Patan Hospital and Bir Hospital have warned that they too will suspend the program if payments are not made. By the end of the Nepali month of Poush (mid-January), outstanding payments were Rs 390 million to TU Teaching Hospital, Rs 140 million to Gangalal, Rs 500 million to Patan Hospital, and Rs 400 million to Bir Hospital.

No source of funds

According to the Health Insurance Board, by providing health services to 50,000 citizens daily, it is bearing a burden of nearly Rs 80 million per day that would otherwise come directly from citizens’ pockets. In other words, without insurance, citizens would have to bear these treatment costs themselves. However, arranging this daily expenditure of Rs 80 million has become extremely difficult for the Board.

The complexity of resource mobilization is evident from the fact that Executive Director Raghu Kafle resigned on 18 January 2026 due to this very issue. He stepped down following conflict with Health and Population Minister Dr Sudha Gautam over budget arrangements.

According to Board data, premiums collected from insured citizens generate about Rs 4 billion annually. Since this amount is insufficient to cover treatment costs, the government provides annual grants. The Ministry of Finance announces a Rs 10 billion grant each year in the budget speech. For the current fiscal year, this amount has been released and paid to hospitals with outstanding claims.

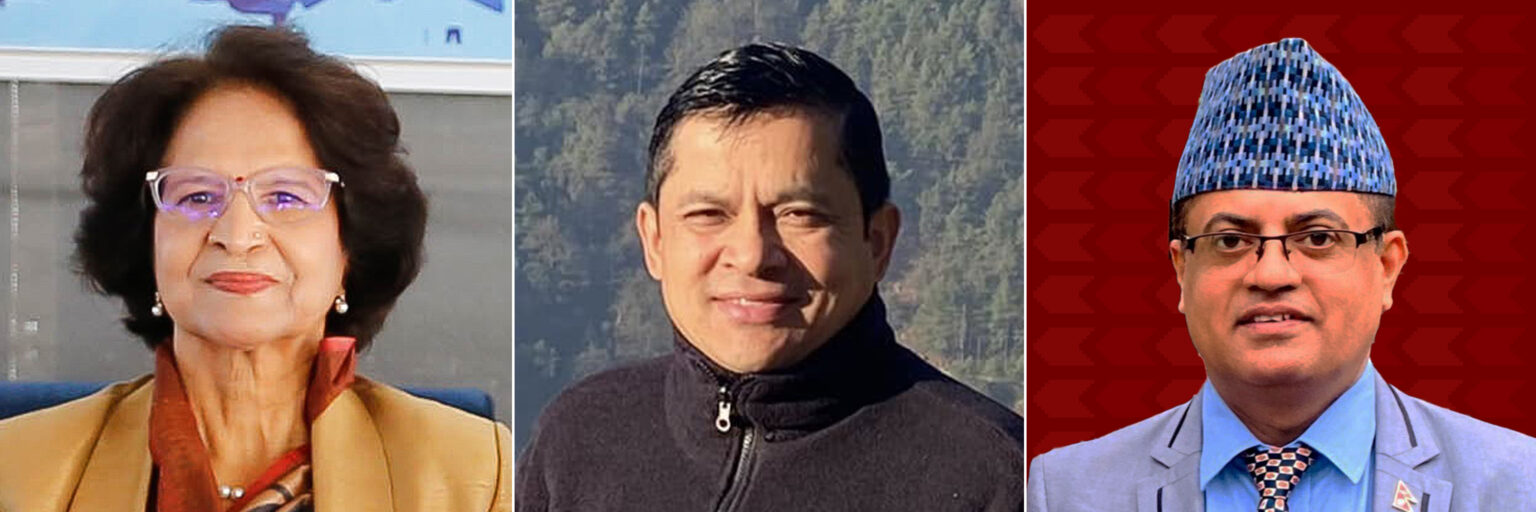

Health Minister Sudha Gautam, Health Insurance Board Chairperson Chandra Bahadur Thapa, and Board Executive Director Krishna Prasad Paudel

Additionally, in the Nepali month of Ashoj this year (mid-September to mid-October 2025), the Board requested Rs 7.083 billion from the Ministry of Finance for immediate payments. However, citing lack of resources, the Ministry provided only Rs 1 billion. Even after paying hospitals with this amount, outstanding dues remain. Malla explains, “In the current fiscal year, Rs 12.74 billion has been paid to various hospitals—Rs 1.74 billion from premium collections and Rs 11 billion from the Ministry of Finance. Now, without further government grants, there is no situation in which hospitals can be paid.”

Claims up to mid-April 2025 have been fully settled. Of the claims from mid-April to mid-October 2025, only 46 percent has been paid. Including the remaining 54 percent and claims up to the end of the Nepali month of Poush (mid-January 2026), a total of Rs 12 billion remains unpaid. The Board’s liability increases by Rs 2.5 billion every month, and by the end of the Nepali month of Magh (mid-February 2026), total liabilities will exceed Rs 14 billion.

According to Board data, in fiscal year 2081/82 (2024/25), as much as Rs 13.48 billion was paid for citizens’ health treatment. Liabilities of Rs 19 billion were carried forward into fiscal year 2082/83 (2025/26). In the current fiscal year alone, the Board estimates that it must pay around Rs 26 billion. Including previous liabilities, the Board entered the current fiscal year with a total liability of Rs 45 billion. After subtracting the Rs 12.74 billion already paid, approximately Rs 32.26 billion remains payable by the end of the fiscal year—without any guaranteed source.

Health Insurance Board Chairperson Chandra Bahadur Thapa says there is no way to clear the remaining dues unless the government provides funds. “Fifty-five percent of those covered by health insurance are from targeted vulnerable groups. The government cannot evade responsibility toward them,” he says, “There was an agreement with the Ministry of Finance to clear all outstanding dues up to Ashoj (mid-October 2025). They asked us to submit details quickly, so we assigned 180 medical officers to prepare the calculations and submitted claims worth Rs 7.083 billion. But the Ministry provided only Rs 1 billion. Without government funding, there is no alternative to paying the remaining claims.”

As major hospitals have started halting insurance-based services citing inability to manage operational and treatment costs, the health insurance program appears to be heading toward failure. As a result, poor citizens who joined the program under the government’s policy promising treatment benefits after paying premiums are now being deprived of healthcare despite having paid.

Meanwhile, Tanka Prasad Pandey, joint secretary and spokesperson of the Ministry of Finance, says a final decision on funding has not yet been made. “An amount Rs 1 billion more than the allocated budget has already been paid. Future payments will be decided based on necessity, justification, and availability of resources,” he says, “The Ministry of Finance has not completely closed the door on payments. Discussions can take place if a proposal comes from the Ministry of Health.”

Why couldn’t resources be mobilized?

The Health Insurance Act, 2017 mandates that every Nepali citizen must be enrolled in the health insurance program. However, even after ten years of implementation, only about 30 percent of citizens are enrolled, according to Board data.

The Health Insurance Regulation, 2018 requires a family of up to five members to contribute Rs 3,500 annually. In return, family members are entitled to treatment services worth up to Rs 100,000.

The regulation also states that employees in the organized sector—civil servants and employees working in various institutions—must contribute 2 percent of their monthly salary to the health insurance program, with 1 percent contributed by the employee and 1 percent by the government/employer. However, the government has not enrolled civil servants in the health insurance program at all.

The health insurance program was designed so that contributions made by those who earn more would be used to provide services to citizens with weak economic conditions. For that very purpose, the law requires employees in the organized sector to contribute two percent of their income. However, due to the failure to effectively implement the provisions of the Health Insurance Act and its regulations, the insurance program itself has been gradually collapsing.

Health financing expert Suresh Tiwari says that problems have arisen because the government lacks commitment in implementing the health insurance program. “There is a difference in perspective between the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Health regarding health insurance. They should have a unified commitment. Due to the incompetence of policy-making bodies, the health insurance program has not been effective,” he says.

The Ministry of Finance has stated that it cannot provide a large subsidy for health insurance. Officials believe that when the government is already struggling to mobilize resources for recurrent expenditure and infrastructure development, it is not immediately possible to provide sufficient subsidies to sustain the health insurance program.

On the other hand, government employees are unwilling to enroll in health insurance, citing the concessions available at hospitals designated for civil servants and the support provided by the Employees Provident Fund (EPF). The Civil Service Hospital provides 40 percent discounts on medical treatment for employees. The EPF provides up to Rs 100,000 per year for treatment of common illnesses, and in cases of critical illness, employees receive up to Rs 1 million over their entire service period. For the current fiscal year, the government has allocated Rs 641.4 million to the Civil Service Hospital Development Committee.

Separate hospitals are operated for the Nepal Police, Armed Police Force, and the Nepali Army. These hospitals also receive annual government subsidies. For the current fiscal year, the government has allocated Rs 1.1659 billion to the Nepal Police Hospital, Rs 1.0581 billion to the Armed Police Force Hospital, and Rs 2.1669 billion to the Birendra Military Hospital. In total, the government has provided Rs 5.0323 billion in subsidies for these four hospitals in the current fiscal year.

Not only that, the Ministry of Health is also running the Poor Citizens’ Medicine and Treatment Program, for which Rs 6 billion has been allocated. Additionally, the Ministry is spending Rs 2 billion on the Safe Motherhood Program.

Health financing expert Tiwari says the health insurance program has been ineffective partly because the government continues to spend on parallel healthcare subsidy programs.

“If the parallel health assistance programs run by the government are integrated, health insurance can be effective. There would be no need to operate multiple separate subsidy programs,” he says.

According to Tiwari, if civil servants, security personnel, teachers, along with banks, financial institutions, and corporate houses are brought under the health insurance umbrella, an estimated Rs 14 billion in annual premiums could be collected. “If all these sectors are included, premium collection can be increased from Rs 4 billion to Rs 10 billion annually. The Rs 8 billion that the Ministry of Health is spending under different headings can be integrated into health insurance itself. Adding the government’s Rs 10 billion subsidies, the program would amount to Rs 44 billion annually,” he says. “With government commitment, there would be no situation in which the health insurance program cannot function.”

The Health Insurance Act states that the responsibility for health insurance should be shared by local, provincial, and federal governments. However, so far, local and provincial governments have not allocated budgets for the health insurance program. Instead, they are operating separate health service programs of their own.

Additionally, the Social Security Fund operated by the government is also running healthcare programs. Of the contributions made by contributors to the Social Security Fund, 1.67 percent is allocated for health services. Tiwari says this would be more effective if it were integrated into the health insurance program.

Board Chairperson Thapa also says that despite repeatedly urging various government bodies to integrate scattered health-related programs, there has been no response. “There are health programs under different ministries with expenditures ranging from Rs 30 to 35 billion. We have even told the Prime Minister to include them under health insurance, but there has never been any response,” he says.

Thapa also says the government has been indifferent in implementing the provisions of the Health Insurance Act. Although the Act mandates that every Nepali citizen be enrolled in health insurance, civil servants have still not been enrolled in the program.

The EPF model

The EPF, established to provide benefits to civil servants, spends around Rs 600 million annually on employees’ health treatment. However, contributors do not receive reimbursement for outpatient department (OPD) treatment. They receive benefits only if hospitalization costs exceed Rs 10,000. The EPF policy provides up to Rs 100,000 per year for treatment of a contributor’s spouse, and Rs 1 million once during the entire service period in cases of critical illness.

EPF Chief Manager and Spokesperson Damodar Prasad Subedi says the Fund allocates 10 percent of its annual profit for members’ health treatment benefits. Contributors must first pay treatment costs themselves and then claim reimbursement from the Fund. To claim reimbursement, official hospital bills along with a recommendation letter from hospital administration and a photograph of the patient are mandatory. “If we were to cover all OPD treatment costs, the annual expense would exceed Rs 2 billion, which the Fund cannot afford,” says EPF Spokesperson Subedi.

The EPF has set aside Rs 6 billion in a reserve fund specifically for contributors’ health treatment benefits. According to Subedi, this amount ensures health treatment support for contributors for the next 10 years.

Efforts for reform

On 9 January 2026, a workshop was held with the participation of Health and Population Minister Dr Sudha Gautam, officials from the Health Insurance Board, and provincial government representatives. During the workshop, Minister Gautam stated that provincial governments must also bear responsibility for health insurance as stipulated by the Act. Various suggestions were presented at the workshop to save the health insurance program, including full implementation of legal provisions and revisions to the co-payment system.

Based on a decade of experience, the Board concluded that the highest number of claims came from outpatient (OPD) services. As a result, it has decided to limit OPD treatment coverage to a maximum of Rs 25,000 per year. Insured citizens will now receive treatment coverage of up to Rs 100,000 only in cases requiring hospitalization. Previously, by paying an annual premium of Rs 3,500, a family of five was entitled to treatment services worth up to Rs 100,000 per year, without any distinction between OPD and other services.

Health Insurance Board Executive Director Dr Krishna Prasad Paudel says, “The previous Board meeting had decided to reduce benefits. We will soon implement this decision. To save the health insurance program, we are currently in a position where we must move forward with some unpopular decisions.”

The Health Insurance Board has also decided that hospitals cannot maintain separate pharmacies with different prices for insured and non-insured patients. “We have informed hospitals that they cannot charge one price for insured patients and another for others. We have written to the hospitals making it clear that all medicines must have the same price,” says Paudel.

According to him, the Board has also decided that patients cannot be referred to higher-level or larger hospitals solely at their request when services are available at local hospitals. In such cases, insurance claims will not be reimbursed. “As long as services are available, treatment must be received at the first-level hospital. Insurance payments will be made only when referral to another hospital is necessary due to unavailability of services,” he says.

Health financing expert Tiwari warns that if health insurance is not made effective and is eventually shut down, political parties that claim to believe in a welfare state will have nowhere to show their faces.

If the state ensures timely payments, strengthens institutional capacity, and restores public trust, the program can become a powerful tool of social security. Otherwise, it will remain merely an ambitious but incomplete effort.