A ‘PhotoVoice’ exhibition at Nepal Art Council documents the lived realities of women working in adult entertainment, revealing stories of survival, exploitation, and resilience

KATHMANDU: If you visit the ongoing exhibition at the Nepal Art Council in Babarmahal, one photograph is bound to arrest your attention: a young woman in a college uniform pouring alcohol from a plastic mug into a steel glass.

That photograph belongs to Mamata Pariyar (name changed) from Sindhupalchowk, whose mornings are spent in college and evenings in the darkness of a local tavern. College is her desire; the tavern is her necessity. In college, she finds the environment and company she chooses; in the tavern, she must endure everything from labor exploitation by the hotel owner to inappropriate touches from customers.

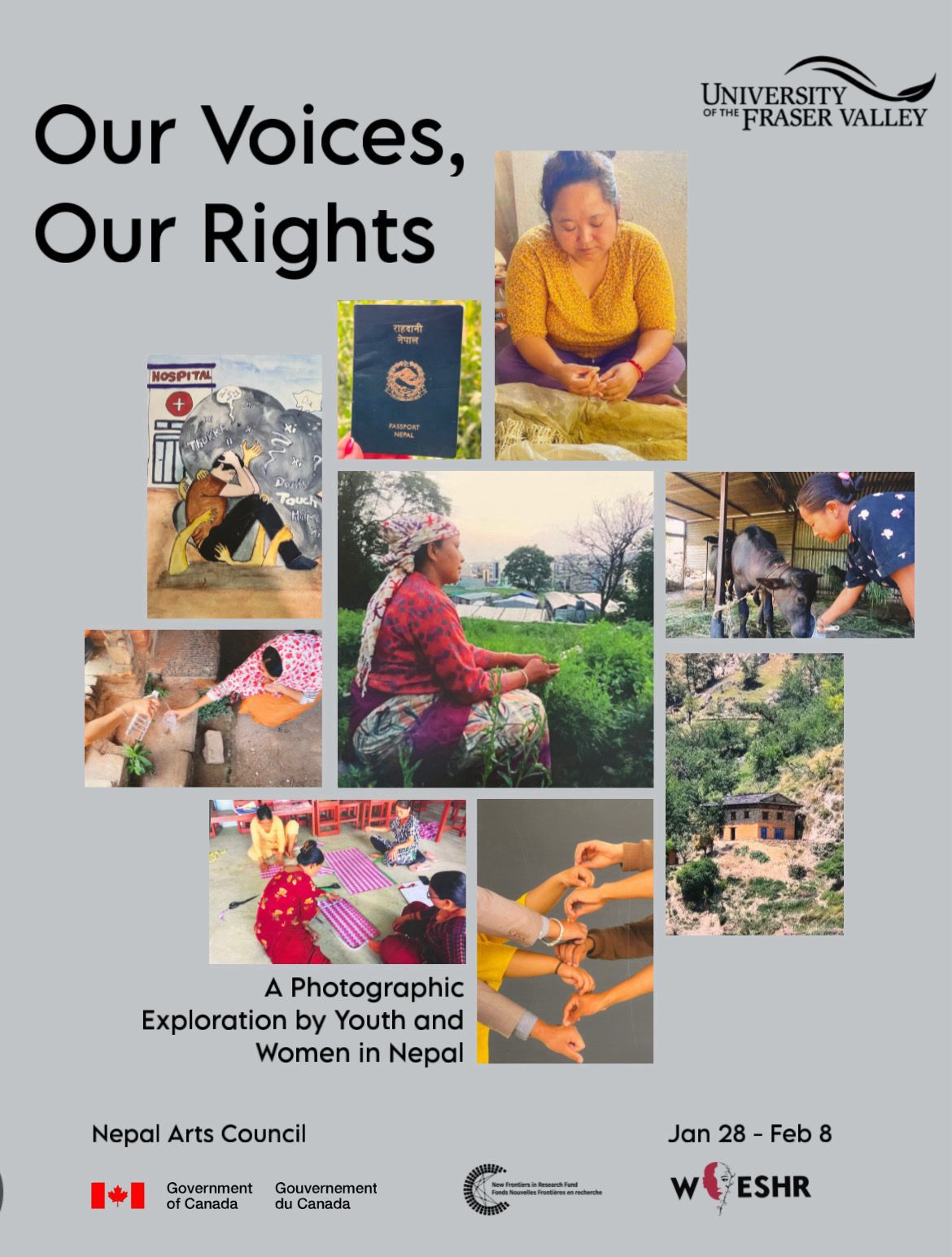

The exhibition titled ‘Our Voices, Our Rights’ includes diverse photographs of youth and women. The exhibition, which speaks the voices of these groups through pictures, has also been named ‘PhotoVoice.’ Within the ‘Adult Entertainment’ section of the council, about 50 photographs from 15 women like Pariyar are collected.

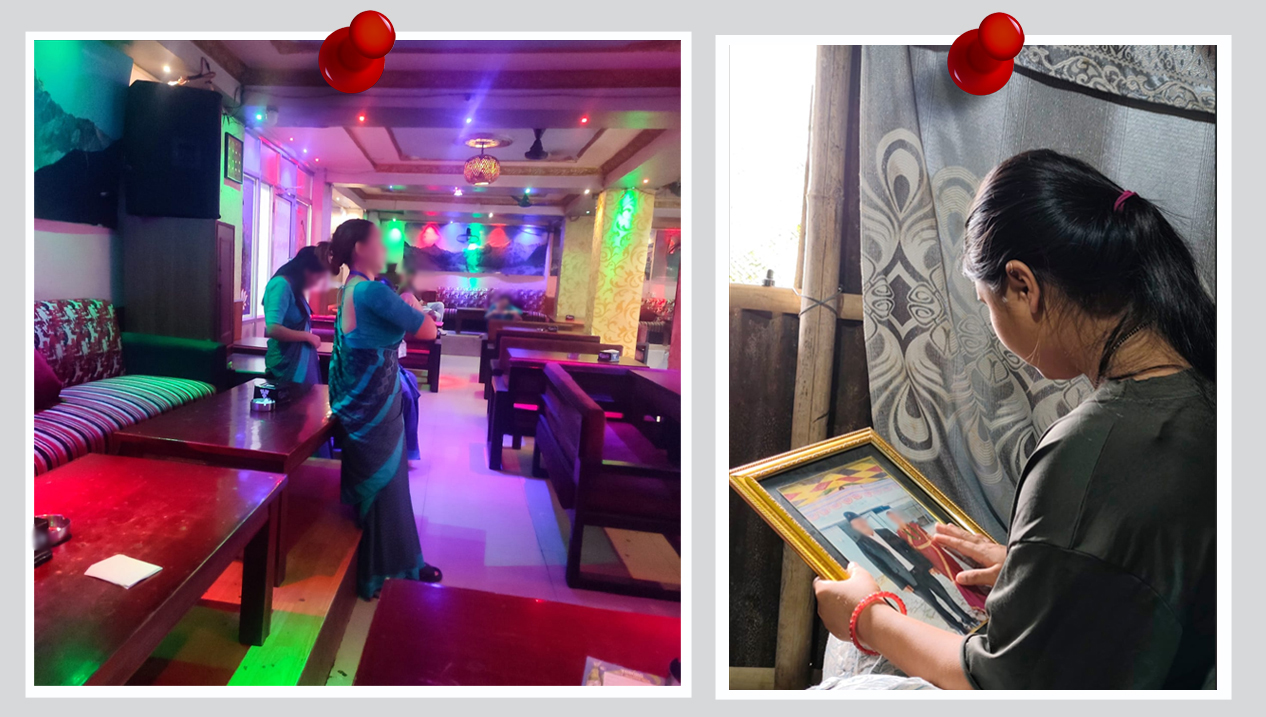

Dohori (Nepali folk duet) evenings, dance bars, restaurants, massage centers, guest houses, small hotels, or taverns are considered adult entertainment sectors. This is a sector where female workers are viewed not as human beings but as objects of consumption. Here, customers expect to receive physical pleasure from the workers. And, due to economic necessity, many women are forced to trade between their bodies and money. The photographs kept in the exhibition cover the stories and pain of women who make a living by enduring such helplessness.

In those photographs, along with the activities in the areas where they work, there is a depiction of their private lives, daily routines, places where they live, and the problems and concerns of public life. In some photographs, a mixture of reality and imagination can also be found.

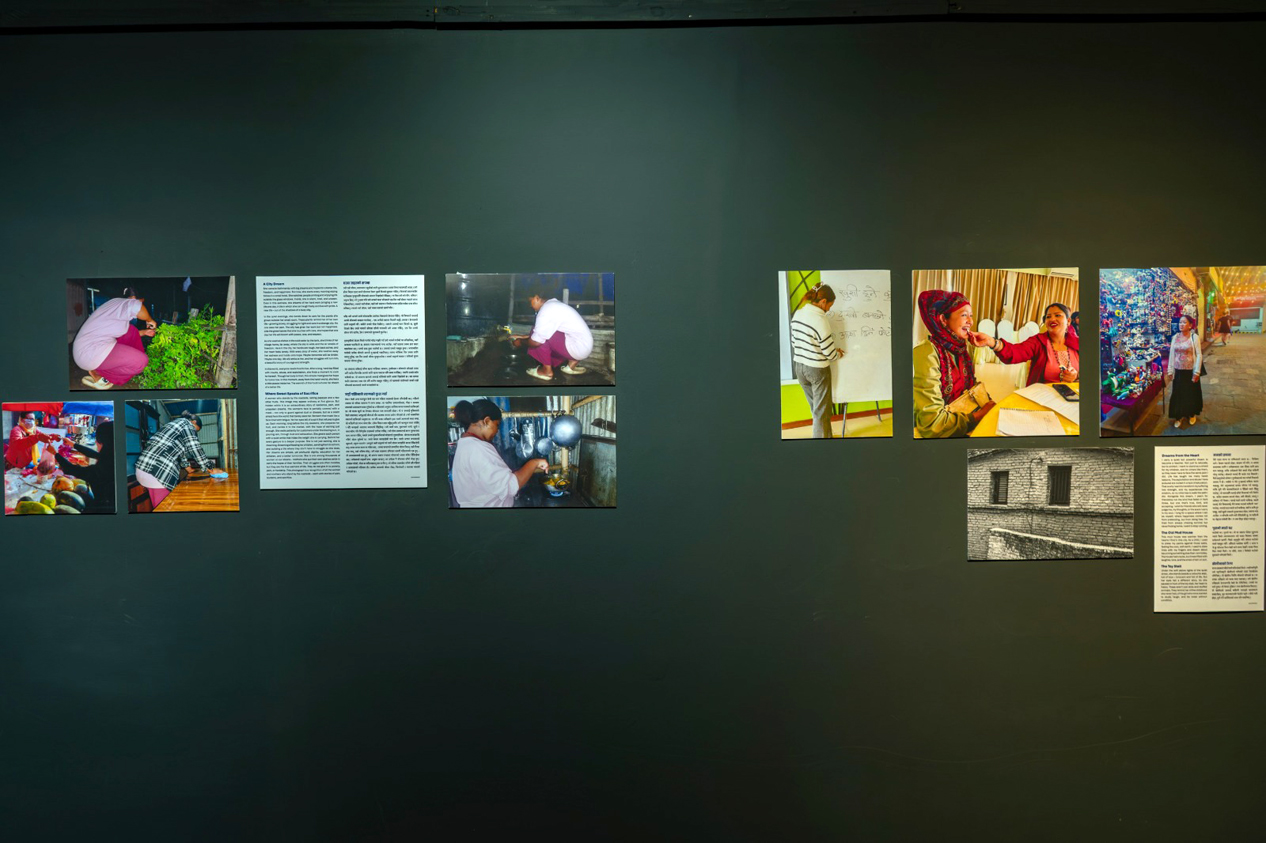

Exhibition wall of the adult entertainment section of the Nepal Art Council. Photo: Bikram Rai?Nepal News

In those photographs, reflections of experiences ranging from economic deprivation to sexual exploitation, family trauma, and caste discrimination are visible. Depicting emotions suppressed within the glamour of the adult entertainment sector, these photographs include the participants’ past and present.

On the signboard of the Ozone Dance Bar, a photograph of Bollywood and former adult movie actress Sunny Leone is seen in the outfit from the song Laila O Laila from the movie Raees. As colorful as the signboard, the lives of the female workers who dance and work there are equally dark.

Other photographs present similar tensions between darkness and light, their impact deepened by long, powerful captions. One reads, “This is our work. It is not the work of our choice. It is the work we do because no other doors are open to women like us.” It concludes with a stark line: “We hide our pain with makeup.”

Januka Rai (name changed), who previously worked as a dancer in a Dohori evening bar, is the facilitator connecting the characters participating in these photographs. At one time, she herself worked at a Dohori evening in Thamel. According to her, the age of the women participating in the exhibition is around 18 to 30. Among those women whose identities are kept secret, there are women from the Dalit, Tamang, Gurung, and Brahmin communities. Geographically, there are women from Sindhupalchowk District to Sudurpashchim province.

Photographs kept in the exhibition of the Nepal Art Council

Januka says she ended up working in the hotel line due to circumstances when the responsibility of raising her three-year-old daughter and seven-year-old son fell on her shoulders after her husband left her.

“I was compelled to take whatever work I could find. While searching for a job, I ended up in the hotel line. There, it became clear that refusing to let people touch my body would make it impossible to keep the job. For my children’s future, I was forced into a compromise I never imagined,” Januka added.

This is not just her compulsion. She says the pain of many women who enter the city from villages and work in hotels, Dohori evenings, restaurants, and dance bars is like hers. She further adds, “Even without wanting to, many sisters are forced to engage in sex work to protect the existence of themselves and their children. Because society seems to be more interested in a woman’s body than her skills.”

Having successfully escaped with self-confidence from her bitter past experiences, Rai is currently active institutionally to help women working in the adult entertainment sector. She says that family-social obstacles, domestic violence, gender abuse, mental exploitation, physical assault, sexual violence, and humiliation are the common pains of women of all age groups. Despite shared sorrows, the experiences of every participant are also distinct.

Among the participants, there are young women from those who came to Kathmandu with a dream of becoming a nurse to a teenager who was raped by her boyfriend. There are women who had to endure violence during the Maoist conflict period and even during foreign employment.

photographs kept in the exhibition of the Nepal Art Council. Photo: Bikram Rai

The adult entertainment sector is an economically and socially risky profession. Due to the government’s neglect, those involved in it are legally insecure as well. Being considered ‘undignified,’ social exclusion is another big challenge. Therefore, they are forced to hide their work and identity. “Our profession is risky; health deteriorates; there is a risk of contracting HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. As age increases, problems of rejection and not finding work are added,” Januka says. “The photos in the exhibition have tried to cover all these problems.”

Some photos in the exhibition speak directly, while some speak symbolically. Stone spouts, flowers, and empty wicker baskets are such symbolic photographs, which express the feelings of elderly women. “When we became old, our faces started to wrinkle, and we started to become weak. After that, everyone left us. Like the stone spout, today we are all alone,” is written in the caption of the stone spout.

In the caption titled ‘Between Struggle and Hope,’ it says, “A flower also blooms beautifully at one time; eventually it keeps withering. Similarly, our identity is also becoming faded. We are facing limited opportunities and continuous abuse. Our work is like that flower. We are used as much as possible and neglected after.”

The caption titled ‘Woman’s Life is Like a River’ is equally heart-touching, stating, ‘A river is born in one place. After that, it flows continuously. Where does it reach and end? It is not known.’

Amidst such uncertainty, 32-year-old Rupa Ghatani from Sindhupalchowk, who was forced to become homeless in Kathmandu, has remembered her village home through a photograph. The photograph of the house made of mud, stone, and wood is the only visualization of her childhood memory.

One of the exhibition photos at the Nepal Art Council

Having lost her mother at the age of six, she had to grow up facing caste discrimination in the village from a young age. After marriage, she had to endure beatings from her husband. After the husband went abroad, he neither sent money nor showed any kind of familial responsibility or affection. The house also collapsed in the earthquake of 2015. She, who did not get to go to school, wanted to make her children educated by any means. Entering Kathmandu at the age of 26 carrying three children, she was in confusion about ‘where to go, what work to do.’ She says, “While wandering in search of work and money, I arrived here, falling from one swamp into another.”

Ghatani, who had never taken a photograph herself in her life, considers being able to participate in this exhibition a great achievement. “I am an uneducated person; in the village, even letters had to be read out by others. My photo was never kept on the wall of the house. I am amazed to see people coming to see my photo here,” is her statement.

The feeling of Sita Tamang, who took a photograph of an old mud house, is also touching: ‘Mud house. Old house. This house was warmer than the hearts found in the city.’

The photos and captions of every character have expressed pain on one side and their desire for education, employment, and living freely on the other. These citizens, neglected by the government and society, want to be heard/poured out. The photographs kept in the exhibition are not merely photographs. These are the cries of countless women, which their families did not hear, society did not understand, and the system did not care about at all. All 15 women participating in the art council’s exhibition had a dream of working and living with self-respect, being educated, and being independent. But that desire and dream of theirs did not get the environment to grow due to the complexities and circumstances of life.

There is life within every photograph hanging on the wall of the adult entertainment section of the council. There is an intense desire to live a life with peace and respect. Captions like ‘From Shadow to Light,’ ‘Golden Grains of Hope,’ ‘Between Struggle and Hope,’ ‘Where Sweat Talks of Sacrifice,’ ‘A Scream for Self-Respect,’ and ‘A Story of Pain, Strength, and Existence’ also indicate those desires. The intent and the message contained in these photos are the same, stating, “Let’s say no to violence.”

However, this is not a story of sympathy; it seeks empathy. The photographs and words of every participating woman are pieces of resistance they made to regain the self-identity they lost in the past. Rai, who has been advocating for women in the adult entertainment sector, says, “The number of women like us is about 87,000. We too are entitled to identity.”

Dwarika Thebe, a researcher, states that in the exhibition organized in collaboration with the University of the Fraser Valley and Women Youth Empowerment in Social Service and Human Rights (WYESHR)-(Sindhupalchowk), the group at risk of exploitation, violence, and abuse was mobilized as co-researchers. She says, “This exhibition has been organized to express, understand, and make others understand the experiences of youth and women from various backgrounds identified as an extremely sensitive group through the medium of photos.”

Apart from adult entertainment, the exhibition covers photographs of subjects related to youth and women, such as gender discrimination, LGBTIQ+, sexuality, mental health, unemployment, friendship and family, and agriculture. The exhibition, which started on January 28, will continue until February 8.