Nepal’s oldest textile brand blends royal heritage, health-friendly fabric, and timeless design to captivate a new generation at home and abroad

KATHMANDU: Memories of a maternal home are always deeply cherished. For Suruchi Khadka, the only niece of the Rana clan, visits to her maternal home in Maharajgunj carried a quiet sense of wonder. The clothes worn there felt different, almost extraordinary. Their exceptional softness wrapped the body in comfort, leaving an impression that lingered long after childhood.

As a result, Khadka’s earliest memory of her maternal home is the gentle warmth of muslin against her skin. That childhood sensation has since become her identity. Dambar Kumari garments were part of everyday life in her maternal household, and for the past six years, she has been working to revive and expand the brand among a new generation through Aama’s Creation. In her work, memory and a deep sense of belonging are inseparably woven together.

“My maternal aunt used to sew Dambar Kumari garments herself, which taught me to recognize fine muslin from a very young age,” Khadka says. “For me, Dambar Kumari is not merely a brand or a type of clothing. It is deeply tied to my childhood, my family, and my lived experience.”

Dambar Kumari is both a name and a legacy. As Khadka explains, it is a three-layered garment crafted from cotton muslin, traditionally block-printed using age-old techniques.

The garment consists of two plain layers placed above and below a centrally printed ‘chipuwa’ layer. As this technique was introduced in Nepal by Dambar Kumari, the daughter of Jung Bahadur Rana, her name eventually became synonymous with the craft. The shawl she pioneered in the 19th century later gained wide recognition as the ‘Dambar Kumari Shawl.’

Emerging from a royal milieu, Dambar Kumari gradually evolved into a household garment. Entrepreneur Suresh Rimal, born around 1964, notes that it was worn as formal attire during the Rana era.

A display of traditional Dambar Kumari products. Photo Courtesy: GARVA गर्भ/Facebook

Little is documented about Dambar Kumari’s life. Available accounts suggest that after the marriage of Jung Bahadur Rana’s daughter, Vishnu Divyashwari Devi, to the Maharaja of Banaras (Varanasi), Prabhu Narayan Singh, Dambar Kumari also traveled to Banaras.

According to Subodh Rana, the trade of block-printed cotton from India to Babylon dates back to the time of the Buddha. Varanasi was then a major center of block printing, known for intricate designs such as the ‘Tree of Life,’ crafted using finely carved wooden and metal blocks, sometimes exceeding one hundred blocks for a single pattern.

Rana writes in his blog that Dambar Kumari, upon reaching Banaras, became so captivated by this ancient art of cotton block printing that she nearly forgot Nepal itself.

Even Jung Bahadur’s strenuous efforts could not return Dambar Kumari, who was settled in Banaras. It is said that Dambar Kumari returned to Kathmandu only after Jung Bahadur’s beloved wife, Putali Maharani, gave assurance through a personal letter that she could do the work she desired.

After this, the cottage industry she started to prepare beautiful shawls with prints became a popular Nepali brand over time. Initially attracting the generations within the palace, the Dambar Kumari shawl has now tempted new generations within the country and abroad.

Even after the end of the Rana regime, Dambar Kumari garments continued to be worn within the royal household. Adil Khan, grandson of Mobin Khan, who ran a Dambar Kumari printing factory in Butwal about four decades ago, says members of the royal family remained regular users. He recalls that King Birendra himself wore fabrics produced by their factory.

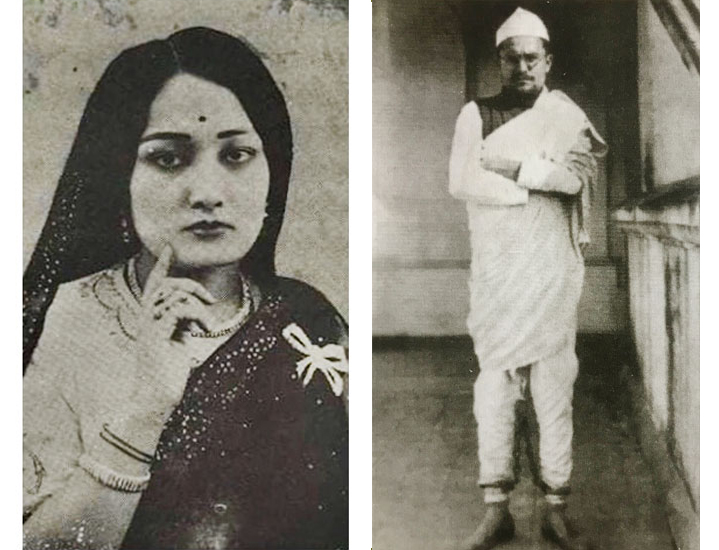

In Jang Bahadur’s family portrait, Dambar Kumari is marked within the white circle. Photo Credit:Sunil Ulak/Facebook

History collector Sunil Ulak writes that the refined version of the cap Dambar Kumari once placed on her father Jang Bahadur Rana later evolved into what is now known as the Dhaka cap. By adding a muslin layer suited to Nepal’s cold climate over block-printed fabric, she enhanced both warmth and practicality.

A poignant love story is also woven into the legacy of the Dambar Kumari shawl. In his article ‘Nepal’s First Fashion Designer Dambar Kumari,’ Sunil Ulak recounts the romance between martyr Dashrath Chand and Julia Maiya. The shawl seen in Chand’s iconic photographs is a Dambar Kumari shawl. Ulak notes that Chand was wearing the same shawl when he faced bullets at Shobha Bhagwati while sacrificing his life for the nation’s freedom. The shawl had been a gift from his beloved, Julia Maiya Saheb.

Julia Maiya, daughter of then Commander-in-Chief Rudra Shumsher Rana, and Dashrath Chand had received family approval for marriage. Preparations were underway when the wedding was postponed due to a death in the family. Around the same time, Juddha Shumsher, the then Shree 3, removed Rudra Shumsher from the line of succession and exiled him to Palpa with his property confiscated. Julia Maiya accompanied her family and later died there of tuberculosis.

Devastated by her death, Dashrath Chand never married again and never parted with the shawl she had given him.

Julia Maiya Saheb and Martyr Dashrath Chand

Suresh Rimal, who started ‘Nepal Grihini Udhyog’ in the fiscal year 1989/90, is one of the old businessmen selling Dambar Kumari clothes in Kathmandu. Ready-made clothes for newborns and postpartum mothers are available at SISU store he operates in the Maitidevi area. He gives an example from within his own house: “In our house, mothers used to wear the three-layered Dambar Kumari Chipuwa. Many old residents of Kathmandu know this custom well.”

Besides shawls, Dambar Kumari quilts and mattresses were used in every house here. Although it spread to the general public of Kathmandu, Dambar Kumari products were overshadowed in the intervening period. Rimal considers the entry of foreign ready-made clothes in Kathmandu and the disappearance of the habit of wearing hand-sewn clothes as the main reasons.

“But lately, especially in the time after COVID, the process of searching for the Dambarkumari brand has increased again,” Rimal added.

As Rimal further stated, besides Aama’s Creation and SISU Store, the names associated with the production and sale of Dambar Kumari include Sanduk, Mayu Creatives, Ratna Quilt, Tukutuku, and Kokro, among others. These make shawls, children’s clothes, muslin scarves, bedsheets, gowns, masks, quilts, mattresses, blankets, chaubandi, bhoto, and suruwal. The participation of mostly women entrepreneurs and workers is seen in these productions.

Khadka of Aama’s Creation considers the three-layer structure of Dambar Kumari as its specialty. She says that since it helps maintain a balance between body temperature and the environment, it even makes breathing easy.

SISU store in Maitidevi

Khadka, who is also a health worker, says she tested Dambar Kumari sheets and gowns on ten patients when she launched Suruchi Home Care in the 2011/12 fiscal year. The trial, she explains, showed noticeably lower sweat accumulation, fewer skin-related issues, reduced physical fatigue, and improved ease of breathing among the patients.

Khadka describes Dambar Kumari as a health-friendly fabric. Because Aama’s Creation focuses on newborns, pregnant women, new mothers, and people with sensitive skin, she believes the fabric’s relevance and usefulness remain strong. She notes that Dambar Kumari shawls were originally designed for Nepal’s climate, when Kathmandu was far colder than it is today and homes were warmed with charcoal braziers.

Historian Subodh Rana adds that Rana palaces later adopted European fireplaces. Putali Maharani, who suffered from rheumatism, is said to have favored a warm, soft cotton shawl with dark prints gifted from Banaras.

Today, both traditional and modern versions of Dambar Kumari products are available in the market.

Rimal, who continues to follow the traditional style, recalls that when he began, only one or two sellers offered Dambar Kumari. He notes that as the market has expanded, diversity in design and quality has grown. Alongside pure cotton garments, blended versions have emerged that appear shinier and are more affordable, though he considers these merely “Dambar Kumari–style,” not authentic products.

Aama’s Creation products displayed at the exhibition. Photo courtesy: Aama’s Creation.

While hand block printing once defined Dambar Kumari, many designs are now machine-printed. Adil Khan says his family still follows traditional methods.

Khadka adds that despite the rise of imitations, Dambar Kumari’s true value lies in its quality, health benefits, and historical legacy.

Both Rimal and Khadka note that once people try Dambar Kumari products, they return for more. Whether for pregnancy, postnatal care, personal use, or gifts, the brand remains a preferred choice.

Khadka’s creation are now exported to the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, and the UK. Rimal, with nearly four decades in the clothing industry, believes that modest investment from government and private sectors could expand Dambar Kumari’s reach nationally and internationally.

Khadka, an internationally awarded entrepreneur, aims to take the brand abroad. As Dambar Kumari spreads, it also uncovers more of the rich history and stories behind Nepal’s oldest textile brand.