From Jhapa to Kailali, squatter settlements have emerged as decisive battlegrounds in key constituencies where top political leaders are competing. Long treated as a campaign talking point, land rights and ownership certificates are now central demands, making the landless vote a potential kingmaker in the upcoming general election

KATHMANDU: On 3 February 2026, during his election campaign in Jhapa Constituency No. 5, Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) candidate Balendra Shah (Balen) visited a squatter settlement in Kamal Rural Municipality, Jhapa. Locals asked him a question mixed with suspicion: “If you win, will you also run bulldozers in our settlement?”

Balen had been criticized for running bulldozers in squatter settlements along the Bagmati River while serving as Mayor of Kathmandu Metropolitan City. For the upcoming House of Representatives election, the votes of landless squatters in Jhapa-5 are important to him. Trying to reassure them, he said, “Actually, in Kathmandu, the settlements were removed from the riverbanks to save lives. The situation in Kathmandu and Jhapa is different. The squatters here are genuine.”

CPN (UML) Chairman and former prime minister KP Sharma Oli, who has been winning elections from Jhapa-5, had started raising the issue of squatters as soon as there was talk that Balen might contest from the same constituency. After Balen officially filed his candidacy in Jhapa-5, Oli did not miss the opportunity to link Balen’s past actions to influence landless squatter voters. Addressing a meeting of the party’s youth wing, Rastriya Yuva Sangh’s regional coordination committee in Jhapa-5 on 22 January 2026, Oli said that “squatters in Jhapa are afraid that a bulldozer-wielding person is coming.”

The day after Balen met the squatters in Kamal Rural Municipality, Oli mocked Balen’s remarks at an event in Kathmandu, saying, “So houses are demolished with bulldozers to save squatters’ lives? What strange things we have to hear!”

RSP candidate in Jhapa-5, Balendra Shah, holding a discussion with squatters of Kamal Rural Municipality

There is a specific reason why both Balen and Oli, candidates for the House of Representatives election scheduled for March 5 in Jhapa-5, have prioritized the issue of landless squatters. The votes of squatters could be decisive in this constituency. Understanding that whoever influences the squatter settlements here will have an easier path to victory, both are working hard to attract their votes.

Jhapa-5 is the constituency with the highest number of voters in the district. It includes the district headquarters municipality, Kamal Rural Municipality, wards 1 to 8 of Gauradaha Municipality, and wards 1 to 6 of Gauriganj Rural Municipality. There are a total of 163,379 voters in this constituency.

This constituency has a large number of landless Dalits, squatters, and unmanaged settlers. According to data registered with the Land Problem Settlement Commission (LPSC), there are 6,346 squatter families in Damak Municipality, 818 in Kamal Rural Municipality, 2,660 in Gauradaha Municipality, and 2,146 in Gauriganj Rural Municipality, making a total of 11,971 families.

According to land expert Jagat Deuja, an estimated average of three voters per family is generally calculated. Based on this estimate, there are around 35,000 squatter voters in Jhapa-5. This number is highly significant for determining the winner.

Jhapa-2, where former Speaker Dev Raj Ghimire and former Deputy Speaker Indira Rana are competing, is another constituency where squatter voters could influence the outcome. This constituency includes Arjundhara Municipality, wards 1 to 9 of Birtamod Municipality, wards 8 and 9 of Kankai Municipality, and wards 1 to 3 of Buddhashanti Rural Municipality.

According to the LPSC, there are 6,460 squatters in Arjundhara, 2,783 in Birtamod, 6,222 in Kankai, and 6,331 in Buddhshanti -over 21,000 in total. Based on these estimates, there are more than 30,000 squatter voters in this constituency. The Election Commission reports 147,522 total voters here.

Not only these two constituencies, but squatters can significantly influence elections throughout Jhapa district. Out of 713,537 total voters in Jhapa, there are 57,151 squatter families or approximately 150,000 squatter voters.

Chitwan district also has a large number of squatters. There are 41,771 squatter families in Chitwan, translating to over 100,000 squatter voters. In Chitwan-2, where RSP Chairman Rabi Lamichhane is a candidate, the constituency includes Ichchhakamana Rural Municipality, Kalika Municipality, and 10 wards of Bharatpur Metropolitan City. There are 3,610 squatter families in Ichchhakamana, 5,948 in Kalika, and 11,218 in Bharatpur – a total of 20,776 families. This suggests around 35,000 squatter voters in this constituency alone.

Similarly, in Chitwan-3, where Nepali Communist Party (NCP)’s Renu Dahal and RSP’s Sobita Gautam are competing, squatter votes could also influence the outcome. This constituency includes 19 wards of Bharatpur Metropolitan City and Madi Municipality. Madi has 5,438 squatters. Including the 19 wards of Bharatpur, there are approximately 35,000 squatter voters in this constituency.

Another closely watched constituency in this election is Sarlahi-4. Nepali Congress leader Gagan Kumar Thapa and RSP’s Amresh Kumar Singh, among others, are competing here. Squatter voters could also be influential in this constituency.

Sarlahi district has four constituencies and a total of 511,606 voters. There are 32,601 squatter households – around 90,000 squatter voters. In Constituency No. 4, which includes Barahathawa Municipality, there are 3,448 squatter families, according to the LPSC. With 112,494 total voters in this constituency, there are around 10,000 squatter voters. Other municipalities in Sarlahi such as Ishwarpur, Lalbandi, and Bagmati also have large numbers of squatter voters.

Rupandehi-2, where UML Vice Chairman Bishnu Paudel, NCP’s Subhash Pandey, and RSP’s Sulabh Kharel are contesting, is another constituency where squatter voters may be decisive. This constituency includes 13 wards of Butwal Sub-Metropolitan City, four wards of Sainamaina Municipality, and six wards of Tilottama Municipality. There are 110,659 voters in this constituency. All three municipalities have a strong squatter presence. There are 16,892 squatter families in Butwal, 16,149 in Sainamaina, and 8,225 in Tilottama – a total of 41,566 families. Even if less than half of this number fall within this constituency, there would still be around 40,000 squatter voters. In Rupandehi district, which has 672,523 voters, there are 78,990 squatter families – approximately 200,000 squatter voters. This number could be decisive in determining election outcomes.

Huts of landless people on public land in Barbardiya Municipality of Bardiya district. Photo: Courtesy CSRC

In Dang-2, where UML General Secretary Shankar Pokhrel and RSP Joint General Secretary Bipin Acharya, among others, are competing, squatter voters could also influence the election outcome. Dang district has a total of 416,735 voters, and 71,261 squatter households – amounting to over 200,000 squatter voters. Constituency No. 2 includes Banglachuli Rural Municipality, 15 wards of Ghorahi Sub-Metropolitan City, and four wards of Tulsipur Sub-Metropolitan City. According to LPSC data, there are 963 squatter families in Banglachuli, 16,332 in Ghorahi, and 17,886 in Tulsipur – totaling 35,181 families, or about 100,000 squatter voters. Even if only around 35,000 of them fall within this constituency, they could significantly influence the election. This constituency has 133,748 total voters.

Kailali-4, where UML Deputy General Secretary Lekhraj Bhatta is a candidate, is another influential constituency in terms of squatter voters. This constituency includes Godawari and Gauriganga municipalities, the entire Chure Rural Municipality, and one ward of Mohanyal Rural Municipality, with a total of 110,453 voters. There are 19,234 squatter families in Godawari, 12,496 in Gauriganga, and 2,725 in Chure – totaling 31,730 families, or around 80,000 squatter voters. In this constituency, where squatters are in the majority, they have the power to elect whichever candidate they prefer. Kailali district has a total of 551,052 voters and the highest number of squatter families in the country – 133,713 families, or around 300,000 squatter voters.

‘4.5 million’ landless squatter voters

In the House of Representatives election slated for March 5, the total number of eligible voters nationwide is 18,903,689. However, there is no exact data on how many of these are squatter voters. The LPSC maintains records only of families categorized as landless Dalits, squatters, and unmanaged settlers. From these three groups combined, a total of 2,377,960 families have been registered nationwide so far.

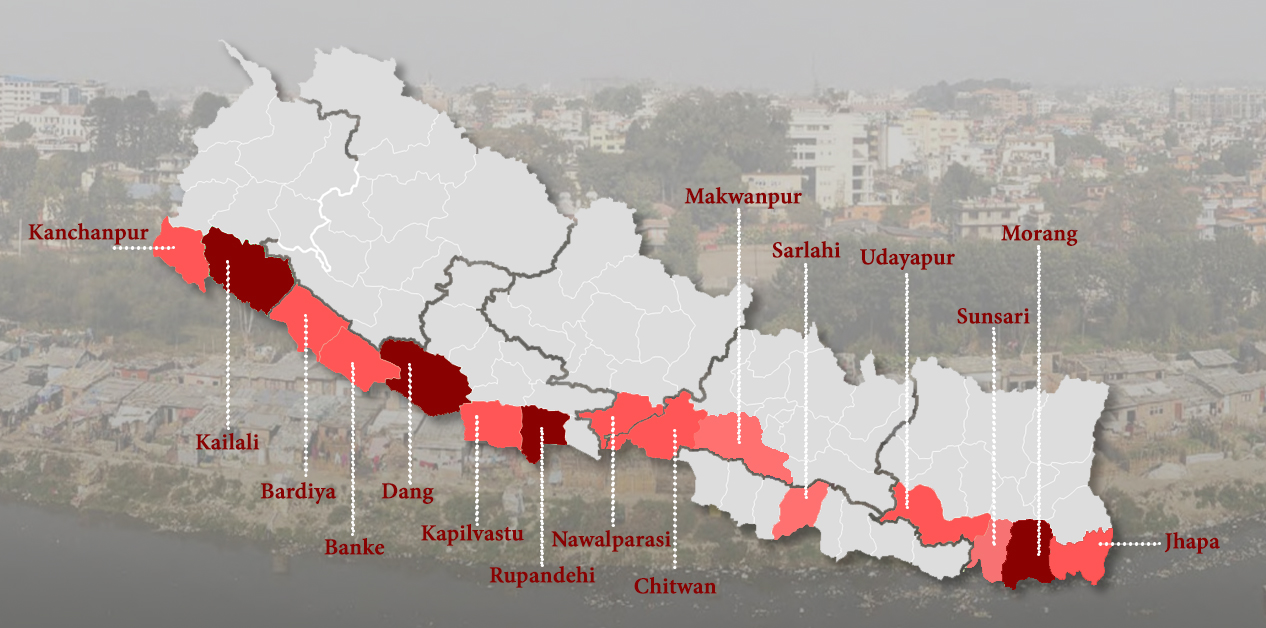

According to land expert Deuja, there are an estimated 4.5 million squatter voters across the country. The 15 districts with the highest number of squatter families are Kailali, Rupandehi, Kanchanpur, Dang, Morang, Jhapa, Banke, Udayapur, Bardiya, Chitwan, Sunsari, Sarlahi, Nawalparasi (East), Makwanpur, and Kapilvastu. These districts, located in the Tarai and inner Madhesh regions, show that squatter votes can significantly influence election outcomes.

Although in the mountain and hill districts the number of landless and squatter voters may not significantly impact elections, Deuja says their influence is considerable in the Tarai and inner Madhesh districts across all provinces, from Jhapa to Kanchanpur. He says, “If voters make informed decisions based on which party is more committed to the landless issue and what efforts have been made in the past, it can influence elections. In many constituencies, their votes alone could be enough to ensure a candidate’s victory.”

Urban poverty and landlessness researcher Sabin Ninglekhu says that compared to previous elections, squatters are more aware this time, which could make a meaningful difference in the results. He says, “Previously, landless squatters voted based on party affiliation. Now they are prepared to vote for whichever candidate carries their issues. This could change the election outcome.”

Only an election agenda

The issue of landless squatters becomes a political agenda in every election. Because there is a significant number of landless squatter voters who can influence elections, parties make it a campaign issue during election time.

During elections, landless squatters also raise their demand for land ownership certificates with candidates. For example, on 8 February 2026, the National Land Coalition, an umbrella organization of 13 institutions related to landless and squatter issues, issued a statement demanding land rights guarantees in party manifestos. Its 10-point demand includes ensuring land ownership certificates and distributing land to the landless.

Although parties include these concerns in their manifestos, the problem is never resolved. On 6 May 2025, the “Bill to Amend Some Nepal Land Acts, 2082” was tabled in the House of Representatives. This bill, introduced by the UML-Nepali Congress coalition government led by KP Sharma Oli, became controversial. It included provisions such as allowing those who had been residing in a place before 2066 BS (mid-April 2009) to continue living there.

Even lawmakers from the ruling Nepali Congress opposed the bill. As a result, the Upendra Yadav-led JSP Nepal withdrew its support from the government. The bill could not be passed after lawmakers from Maoist party and the RSP, who had previously raised the issue of squatters, also opposed it.

Kumar Karki, central president of the Nepal Basobas Basti Sanrakshan Samaj (Nepal Residence Settlement Preservation Society), an organization representing landless squatters, says that trust in political parties has weakened because although they prioritize landless squatter issues in manifestos and speeches, they back away during implementation.

According to him, in the 2008 election, most landless squatters voted for the Maoists. However, the Maoists failed to work in their favor as expected. After that, squatters were divided among the Maoists, Nepali Congress, and UML, and voted similarly in subsequent elections. Karki says, “This time, however, they will not vote based on party as before, but for whoever presents a plan to address their agenda.”

Land expert Deuja also says that landless squatters no longer fully trust either new or old parties. They view the traditional parties – Nepali Congress, UML, and Maoists in the same light. According to him, they are also wary of new parties, particularly due to Balen’s actions. Because Balen demolished squatter settlements in Kathmandu Metropolitan City but did not coordinate with the Land Commission or collect proper data to resolve the issue.

Because they do not fully trust any party, landless voters have begun questioning candidates in this election about their views on squatters and their plans to provide land ownership certificates. Deuja says, “If voters ask candidates how they plan to solve the problem and how they perceive the issue, whoever forms the government may be compelled to consider concrete measures.”

That said, landless squatters and unmanaged settlers are themselves affiliated with various parties. The new generation of squatters is also attracted to new parties. Their lack of unity makes it difficult to focus collectively on their issue. However, Karki says that squatters who had previously divided among different parties in hopes of solving their problems have now become more cautious after losing trust in them. According to him, the organization is running a campaign urging people not to vote for anti-squatter candidates and to support those who bring credible agendas. He says, “Squatter votes will go to whoever can play a role in solving the land problem.”