As open spaces disappear, rivers are constricted, and population density reaches its limits, Kathmandu’s quality of life is steadily declining. Disrupted natural water systems, recurring floods, shrinking population figures, and underutilized development budgets reveal a city struggling to reclaim its urban rhythm

Writer Basanta Thapa, who first entered Kathmandu in February 1970, was captivated by the city’s grandeur. During the month he stayed there, he was mesmerized by the atmosphere around New Road. Even today, he feels delighted recalling how he would stroll to Ason and Indrachowk for shopping, hop on a bus from Ratna Park or Shahid Gate whenever he needed to travel somewhere, slip into Ranjana Hall nearby to watch a movie, browse through American, Indian, Chinese, and Soviet friendship libraries when he felt like reading, and carefree roam with his friends from Dharan who stayed in Thamel hostels.

But New Road is no longer what it used to be. The originality it had 55 years ago has been shattered. When he had come to Kathmandu from Dharan after completing his BA exams, the city’s population was naturally small. Vehicles were few. People did not push and shove as they do now. Kathmandu was free of smoke, dust, and pollution.

However, after the political change of 1990, Kathmandu transformed. Population density soared. Houses mushroomed over fertile fields. Vehicles multiplied. Along with air pollution and noise, sewage began flowing into the once-serene Bagmati River. Waste and pollution increased. The mountain ranges once visible nearby began to be obscured by smog and haze. Open spaces such as Dhobichaur and Lainchaur started shrinking.

Thapa, who has spent most of his life in Kathmandu, has witnessed all these changes. When he was in college, the city had preserved its originality. But after the 1990 political change, as the country’s main administrative and political center, Kathmandu began attracting more people in search of better facilities. Gradually, its native characteristics began to fade.

Traffic jam along the Sundhara–Ratna Park–Bhadrakali–Putalisadak section in Kathmandu. Photo: Nepal Photo Library.

The government also failed to focus on planned urbanization. As a result, Kathmandu did not just change in appearance; it became disfigured. “These days, Kathmandu is like an old tree that has forgotten to sprout new leaves,” Thapa says sarcastically. “This city is no longer a city. Strangely, it has become ugly.”

In an article titled ‘Urbanization in Nepal: An Overview’ published in 2006 by Martin Chautari in a book on urbanization, Professor Pitambar Sharma writes, “The origin of cities in Nepal began in the Kathmandu Valley. Outside the valley, there is no long history of urbanization.”

As Sharma suggests, Kathmandu’s history is not only ancient but also filled with grandeur. However, due to increasing dense settlements in recent years, the country’s oldest city no longer appears “livable.” Infectious disease specialist and activist Dr Anup Subedee says, “Even World Health Organization data suggests that Kathmandu is unlivable. Kathmandu has not truly become a city; it is not fit to live in.”

The country is currently in an election season. As the date for the House of Representatives election, energized by the Gen-Z movement, approaches, candidates across the country are contesting for 275 seats under both direct and proportional representation systems. Yet, none of these candidates appear to have a concrete agenda on how to systematically manage the cities they live in. Even candidates in Kathmandu, the capital itself, riddled with disorder and uncontrolled urbanization, seem confused.

Urban infrastructure expert Arjun Jung Thapa says, “It’s not just this time that urban management has been ignored. The agenda of how to improve rapidly developing cities according to their urban characteristics has never truly been a priority for political parties.”

What a city should be like

Urbanization and population density alone do not make a complete city. A vibrant city requires many dimensions. According to the United Nations’ global framework, cities must ensure accessible and safe housing and uninterrupted access to infrastructure for all. The key feature of a city is that it should be ‘a city for all.’ There must be access to safe drinking water, sanitation, clean air, accessible public transport, quality public services, and the right for people of all castes, languages, genders, classes, and communities to live with dignity.

The promotion of natural and cultural heritage is also emphasized in the new definition of urbanization. Environmental conservation—including water and biodiversity protection—is essential. Open, green, and public spaces are considered mandatory for a quality life. Likewise, the urban economy should ensure equal pay for equal work and be inclusive. Upgrading informal settlements and strengthening trade networks between urban and rural areas are considered essential. With the growing impacts of climate change, disaster risk reduction and adaptive policies and programs are necessary.

About a decade ago, incorporating all these agendas, the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat) introduced a global framework on urbanization. Under this framework, UN member states have set a goal—under Sustainable Development Goal 11—to achieve inclusive, safe, resilient, well-managed, and sustainable cities and human settlements by 2030. This was endorsed at the UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) held in Quito, Ecuador, from October 17–20, 2016. The declaration is known as the “Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All.” The UN General Assembly adopted it on December 23, 2016. Nepal is also a signatory to this agenda. Pragya Pradhan, Programme Manager for UN-Habitat in Nepal, says, “When implementing the global framework in a way that suits the country, cities and development must move forward together in a way that all citizens can internalize. A city must be for everyone.”

Based on this global framework, Nepal has also formulated its own urban policy. The “National Urban Policy 2081BS,” approved by the Council of Ministers on 13 December 2024, aims to make urban areas organized, inclusive, and prosperous.

Applicable nationwide, the policy sets a target to increase urban infrastructure indicators by an average of 15 percent, reaching at least 50 percent by 2036. This policy is not entirely new—the government had introduced a similar policy in 2007 (2064 BS).

The policy incorporates most of the global urban agenda, including strengthening rural-urban linkages; ensuring universal access to basic housing, infrastructure, and services; adequate safe drinking water; a clean and secure urban environment; pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly systems; renewable energy-based public transport; organized public toilets; rest houses; public platforms; parks; community centers; libraries; and sports facilities.

The Kathmandu Valley Development Authority’s master plan (2015–2035) and the Local Government Operation Act, 2017, also include provisions related to safe drinking water, affordable and accessible public transport, urban greenery, and beautification. However, because these urban features remain incomplete and insufficient, Kathmandu has failed to provide the experience of a vibrant city. According to the National Census 2021, as much as 55.53 percent of households in Kathmandu district still live in rented homes.

An ugly Kathmandu

Kathmandu was officially declared the country’s first metropolitan city on 15 December 1995. Before that, it was a municipality. In 1976 (2033 BS), Kathmandu’s urban area covered 20.19 square kilometers. Today, it has expanded to 49.45 square kilometers.

If population is taken as the main basis, urbanization has made Kathmandu chaotic and uncontrolled. A city should be developed based on prior planning—where houses will be built, where agriculture will take place, how wide roads will be, and where and how sewage and waste will be disposed of. Urban planner and Pulchowk Engineering Campus Associate Professor Sanjaya Uprety says, “But here, urban planning begins only after the population increases. That has created problems.”

Nepal’s Fifth National Census (2008–11 B.S.) defined any settlement with a population of more than 5,000 as a town or city. During the Panchayat era, the Town Panchayat Act, 2019 BS set the minimum population requirement for a city at around 10,000. After the implementation of federalism, the Local Government Operation Act, 2017 classified cities into three tiers: metropolitan city, sub-metropolitan city, and municipality. According to this law, a metropolitan city must have a minimum population of 500,000. As per the National Census 2021, Kathmandu Metropolitan City has a population of 862,400.

The same census shows that 17,440 people live per square kilometer within the metropolis. In the 1991 census (2048 B.S.), population density was 8,480 per square kilometer. This indicates that population pressure in the metropolis has increased significantly.

In terms of administrative, political, economic, social, and cultural assets, Kathmandu Metropolitan City is the country’s main hub. Singha Durbar and other key government administrative offices are located here. Universities for higher education, modern hospitals equipped to treat serious illnesses, and other physical infrastructure are also concentrated here. Employment opportunities in both formal and informal sectors are greater here than elsewhere. People from across the country migrate here in search of opportunities.

However, according to Uprety, Kathmandu is suffering today because land-use policies were ignored while expanding settlements. There were adequate water sources, systems for conserving and distributing them, and sufficient public spaces. “As the population increased, houses were allowed to be built everywhere, which gradually narrowed the city’s historical and cultural distinctiveness,” he says.

A frustrating Kathmandu

Having failed in systematic land-use planning, Kathmandu is now grappling with two major challenges. According to urban development expert Padma Sundar Joshi, the first is chaotic public transportation, and the second is unmanaged solid waste. Speaking on content creator Sushant Pradhan’s podcast broadcast on 23 September 2025, Joshi said, “Kathmandu’s main challenge is mobility. The second is waste management.” Crowds are everywhere, and parking problems persist.

The absence of pedestrian-friendly roads makes commuting within the city frustrating. There are roads for vehicles that emit black smoke and worsen air pollution, but footpaths are not available everywhere for pedestrians. There are wide roads for private vehicles that speed noisily, but no dedicated lanes for cyclists. “The largest share of the population walks, yet there are no safe footpaths for them. This is where the mistake lies,” says urban planner Uprety.

Studies also show that public transportation in Kathmandu is poorly managed. A study titled “Enhancing at Crosswalks and Sidewalks: A Case Study of Kathmandu Metropolitan City,” published on 21 December 2025in the ‘Journal on Transportation System and Engineering’, states that 70 percent of roads in the metropolis lack walkable footpaths. This increases the risk of accidents for pedestrians forced to walk on the road.

Similarly, a survey titled “Measuring Mobility Gap: A Quantitative Study of Affordability, Reliability and Safety Issues in Kathmandu’s Public Transport System,” published on 24 June 2025 in the ‘NPRC Journal of Multidisciplinary Research’ found that 34.8 percent of respondents said public transportation is unreliable. Likewise, 43.3 percent reported difficulty accessing public transport services in the evening or at night.

A traffic police officer assisting a wheelchair user with movement. Photo: Traffic Management Police Office Report (2024).

There have also been studies on the economic losses caused by traffic congestion. A 2021 study titled “Economic Impact of Traffic Congestion in Kathmandu Valley,” published in the Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, found that the average daily economic loss per road lane is approximately Rs 174,644. The study examined traffic congestion losses along road sections including Gaushala–Mitrapark, Old Baneshwor–Gaushala, Padmodaya–Putalisadak, New Baneshwor–Tinkune, Tinkune–Koteshwor, Koteshwor–Jadibuti, and Satdobato–Gwarko.

The waste problem stems from indiscriminate dumping, delays by the metropolitan authorities in collecting waste, and the lack of systematic disposal. Similarly, unhealthy air, sewage problems, and rising living costs persist. Kathmandu’s rivers emit foul odors. Although the Constitution guarantees every citizen the right to safe housing, affordable housing is not readily available in Kathmandu, and even where it exists, access is limited.

There are insufficient open, green, and public spaces. UN-Habitat defines roads, open areas, and public spaces collectively as public spaces. According to the 2025 UN-Habitat guideline “Healthier Cities and Communities through Public Space,” 45 to 50 percent of urban land should be allocated for public space—30 to 35 percent for roads and footpaths, and the remaining portion for open public areas. However, public spaces in Kathmandu fall far below global standards.

It has become difficult to find cultivable land within Kathmandu Metropolitan City. According to a 2020 study titled “Public Open Spaces in Crisis: Appraisal and Observation from Metropolitan Kathmandu, Nepal,” published in the ‘Journal of Geography and Regional Planning’, agricultural land in Kathmandu had shrunk to 5.47 percent by 2019. Residential and commercial areas occupied 58.77 percent of the land. In 1980 (2037 BS), 30 percent of the total land area was used for agriculture, while residential and commercial areas covered only 9.5 percent. In 2019, open spaces accounted for 11.27 percent of Kathmandu’s total area—0.30 percent less than in 2011.

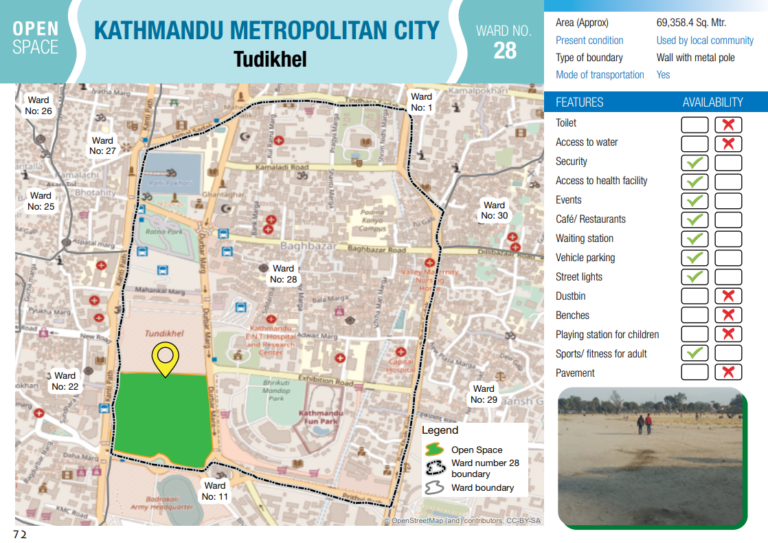

Open space (shown in green) in Ward 28 of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, mapped in 2020. Photo: Open Space Booklet, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

The severe condition of Kathmandu is not just a recent development. Writer Thapa had published a special issue in Himal Khabar magazine in Kartik and Mangsir 2053 (mid-October to mid-November and mid-November to mid-December 1996) titled “The Valley is Suffocating.” The problems highlighted three decades ago remain largely unchanged today. “We published the special issue so that the government would pay attention and move toward solutions. But even today, there has been little sign of meaningful reform,” Thapa says.

Instead, disorderly Kathmandu has begun to lose opportunities. According to Thapa, the number of foreign tourists who once eagerly visited Kathmandu, enchanted by its natural beauty and historical and cultural heritage, has declined significantly. “Few foreigners now come solely to tour Kathmandu. They come to climb mountains and leave after a night or two,” he says, noting that the city’s deteriorating condition is beginning to negatively affect its tourism economy.

Four UNESCO World Heritage Sites lie within Kathmandu Metropolitan City: Pashupatinath Temple, Swayambhunath Stupa, Kathmandu Durbar Square, and Bauddhanath Stupa. However, conservation activist Ganpati Lal Shrestha says that the construction of tall buildings around these heritage sites is encroaching upon their authenticity. Due to weak enforcement of building codes, the heritage sites remain at risk. “Because the importance of heritage has not been effectively communicated at the local level, and people are not engaged in incentive programs, some residents feel deprived—thinking they cannot build desired structures on their own land because of heritage restrictions,” he says.

Plastic waste accumulated in the Ikshumati River between Bhadrakali Temple and Singha Durbar in Kathmandu. Photo: Kiran Raj Bista/Rastriya Samachar Samiti (RSS).

When former Maoist leader Hisila Yami served as Minister for Physical Planning and Works, the 830-meter foot trail known as the ‘Tilganga Tamramarg,’ stretching from Tilganga southeast of Pashupatinath Temple to Guhyeshwari in the northeast, was widened. UNESCO subsequently warned that the site could be placed on the endangered list. Following this, the government closed the road, according to conservation activist Shrestha.

At present, in the Kathmandu Valley, there are no neighborhood parks where children and senior citizens can stroll; even where parks exist, they are not well maintained. Parks have been built along the banks of rivers such as the Bagmati, but these concrete structures have disrupted the natural groundwater recharge cycle. Urban planner Uprety says that infrastructure development and expansion centered on concrete structures have pushed the development of Kathmandu in the wrong direction. “We have ruined this historic and cultural city—indeed, the government itself has ruined it—by laying concrete everywhere. Even the riverbanks, in the name of beautification, have been completely covered in concrete,” he says.

By encroaching upon riverbanks on both sides and constructing parks and other physical structures, the natural flow of rivers has been obstructed. As a result, Kathmandu has had to endure floods and inundation every year, according to Uprety. Frustrated by the daily hardships, residents of the metropolis have begun migrating to nearby semi-urban and rural areas such as Kageshwari and Manohara. “As the quality of life declines, people have already begun leaving the metropolis in search of drinking water, clean air to breathe, and relief from rising living costs,” he says.

Urban development expert Joshi argues that Kathmandu has exceeded the population density it can sustain, which is why its population has begun to decline. Kathmandu is currently ranked as the world’s 16th most densely populated city. “The population has gone beyond what the city can handle. Since there is no vacant land left for expansion, the census shows a population decline,” he says.

According to the National Census 2021, Kathmandu Metropolitan City’s population has decreased by 113,053 over the past decade. The 2011 census recorded a population of 975,453, which fell to 862,400 in 2021.

Efforts to manage Kathmandu and other municipalities began as early as the Panchayat era. The Town Panchayat Act, implemented in 1962 (2019 BS), stipulated that cities must provide roads, bridges, drinking water, and sewage systems. After the restoration of democracy, the Municipality Act 1991 (2048 BS) and the Local Self-Governance Act 1999 (2055 BS) also addressed urban management. Yet Kathmandu’s urban condition remains chaotic.

Despite having sufficient budget and resources, the metropolis has failed to use them effectively to breathe life into the city. Compared to other metropolitan cities in the country, Kathmandu ranks among those spending the least on development budgets. In fiscal year 2024/25, Kathmandu Metropolitan City’s total capital expenditure was only 44 percent. Out of a capital budget of Rs 15.06 billion, only Rs 6.73 billion was spent.

The challenge of restoring urban rhythm

When writer Basanta Thapa visited Bangkok in 1979, it resembled present-day Kathmandu—noisy, overcrowded, vehicles competing aggressively on the roads, and pedestrians jostling through the streets. Seeing Bangkok in that state, he felt a sense of pity. He wondered how people could survive amid such chaos. At that time, Kathmandu was calm and serene. But when he visited Bangkok again in 2023, he was astonished to see how development had transformed the city. “It’s exactly the opposite now—today’s Kathmandu resembles the Bangkok I saw 45 years ago,” he says. “Bangkok’s political situation has also been unstable, but it shows that if there is will, improvement is possible.”

Infrastructure expert and former government secretary Kishore Thapa believes cities can be improved if local governments focus on proper management. The growth of cities, rising populations, and expanding housing are inherent characteristics of urban areas and should not be viewed as problems in themselves. “If properly managed, two or three crore (20–30 million) people can live comfortably in a single city,” he says. “Kathmandu failed in this regard because the local government did not perform its duties. The metropolis must take responsibility.”

Metropolitan spokesperson Nabin Manandhar acknowledges that although urban infrastructure has developed, it remains insufficient. “Regarding open spaces, we are reclaiming encroached land wherever possible and developing parks and playgrounds. But in a core city like this, it is impossible to meet global standards for open space,” he says. However, he adds that citizens’ cooperation is essential to preserve the infrastructure that has been built.

Locals navigating the sidewalk awkwardly on December 05 after Kathmandu Metropolitan City dug up the road at Balaju–Bypass and left it incomplete. Photo: Nepal Photo Library.

Across the country, there are six metropolitan cities, 11 sub-metropolitan cities, and 276 municipalities classified as urban areas under the Local Government Operation Act 2017. The picture of urban disorder in these cities is not very different from that of Kathmandu.

Watershed expert Madhukar Upadhya, who has witnessed Kathmandu’s unplanned urbanization, says, “Cities are being declared across the country, infrastructure is being built without planning, but there is little substantive benefit. Kathmandu’s problems are even more severe than elsewhere.”

Studies indicate that Kathmandu falls short of international standards in environmental policy, emission control, public transportation infrastructure, and green spaces. A study titled “The Political Ecology of Urban Expansion and Air Pollution of Kathmandu,” published on 28 July 2024 in the ‘Journal of Development Review’, concludes that despite government initiatives to control urban expansion and reduce pollution, urbanization has largely become uncontrolled. The study recommends that to improve air quality, preserve urban biodiversity, and make Kathmandu a healthy and livable city, the government must invest in green infrastructure and public transportation.