The “detain first, hear later” justice system adds injustice and increases state expenses for those later proven innocent

In the fake Bhutanese refugee case, since 16 June 2023, nine individuals including former Deputy Prime Minister Top Bahadur Rayamajhi and former Home Secretary Tek Narayan Pandey have been in pretrial detention for two and a half years. It is still uncertain when the verdict will be delivered.

According to the Department of Prison Management, like them, 10,395 people across the country are currently in pretrial detention in various prisons. As per data up to 8 February 2026, a total of 26,960 inmates are in prisons nationwide, including 16,565 convicted prisoners, and those in pretrial detention.

According to the Supreme Court’s 2019 booklet on the rights of detainees and prisoners, a “detainee” refers to a person held in custody by a court, police, or other authority for investigation, inquiry, or trial proceedings. A “prisoner” refers to a person serving a sentence in prison following a decision by a judicial or quasi-judicial body.

The Supreme Court, Special Court, high courts, and district courts issue orders for pretrial detention in cases related to narcotics, homicide, assault, robbery, theft, rape, arms and ammunition, kidnapping, money laundering, corruption, and others. Once a person is taken into custody, the state bears full responsibility for them.

Those placed in pretrial detention may be released by court order. The number fluctuates as individuals are released after completing sentences or when courts order their release.

Until mid-August 2025, there were 28,903 inmates nationwide, including 10,436 in pretrial detention. However, during the Gen-Z protest on September 8 and 9 last year, as many as 14,554 inmates broke out of prisons and escaped. According to the Department of Prison Management, by 10 February 2026, as many as 10,156 inmates had been returned to prison either through surrender or arrest, while 4,398 still remain at large.

In government-initiated criminal cases, once investigation is completed and a charge sheet is filed in court, the accused may be held in custody for trial, released on bail, released on own recognizance, or required to appear on regular dates. No one is guilty until the charges are proven. International human rights law and global standards recognize detention as a last resort.

Attorney General Sabita Bhandari states that judges issue detention orders under powers granted by law, and therefore it is not appropriate to comment on such decisions. She adds, “If either party is dissatisfied with a detention order, they may appeal to a higher court.”

Rs 520 million annual expense

Schedule 3 of the Prison Regulations outlines expenses provided to detainees and prisoners. Each is entitled to 700 grams of coarse rice and 80 rupees in cash daily. They also receive clothing twice a year and 300 rupees for festival expenses.

These are direct expenses. In addition, there are indirect costs. According to Chomendra Neupane, director of the Department of Prison Management, direct costs include food rations, clothing, transfers, and festival allowances, while indirect costs include security and administrative personnel deployed for inmates.

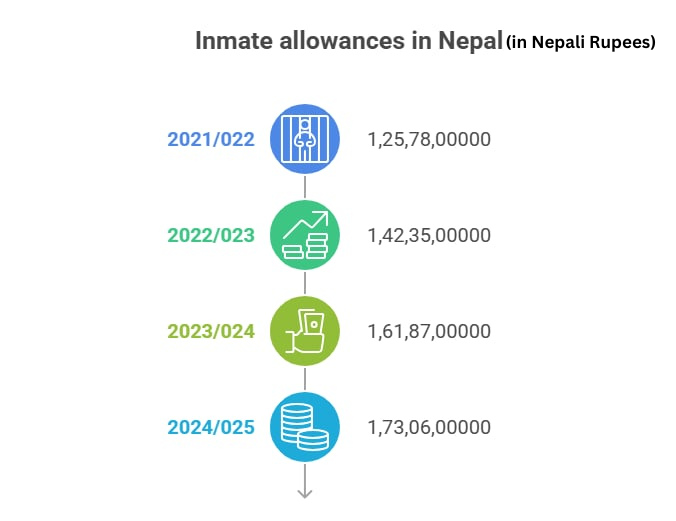

The growing inmate population has increased the state’s financial burden. According to the Department, in fiscal year 2024/25, more than Rs 1.73 billion was spent on inmates nationwide. In FY 2023/24, the amount was Rs 1.61 billion, and in FY 2022/23, it was over Rs 1.25 billion.

The Department states that based on the ratio of inmate numbers to expenses, the average annual direct cost per detainee is currently around Rs 50,000. By this calculation, the 10,436 people currently in pretrial detention cost approximately Rs 520 million per year.

According to the Department, in fiscal year 2024/25, more than Rs 1.73 billion was spent on inmates nationwide. In FY 2023/24, the amount was Rs 1.61 billion, and in FY 2022/23, it was over Rs 1.25 billion.

Krishna Bahadur Katuwal, former administrator and chief of Central Jail at Jagannath Deval, says prisons nationwide incur large direct and indirect expenses. “Because the justice system is slow, those in pretrial detention remain for extended periods,” he says, adding, “Prisoners sit idle all day. If, like in China, the state could engage prisoners in work, it could become more productive.”

Former president of the Nepal Bar Association, Gopal Krishna Ghimire, argues that the principle should be “bail as the rule and jail as the exception.” “Keeping people in jail who may later be acquitted causes additional economic loss to the country. The state should not overcrowd prisons and increase unnecessary expenses,” he says. He adds that once someone is detained, the judiciary must prove guilt. “If a person kept in detention is later proven innocent, there is no provision for compensation. Therefore, people should not be jailed merely upon accusation.”

Contradictions in the law

International norms say, “Hear first, then detain.” A charge sheet should only be filed once guilt is reasonably established. In Nepal, however, the opposite practice – “detain first, hear later” – is prevalent.

The Office of the Attorney General’s “Study and Recommendation Report on Criminal Justice Administration Reform, 2081BS” also concluded that there are loopholes in laws related to pretrial detention. The task force formed on 1 February 2024 under then Attorney General Dinmani Pokharel noted inconsistencies in legal provisions governing pretrial detention. The report recommended that detention-related laws be implemented in a flawless, objective, just, and human-rights–compliant manner.

According to Section 47 of the National Criminal Procedure Code, 2017, “An accused who confesses to the offense and assists the court is entitled to a reduction in sentence.” On the other hand, Section 67(2)(a) provides for keeping an accused in pretrial detention without even considering what sentence may apply solely on the basis that the accused has confessed in court. The report states that this legal contradiction requires amendment.

The Criminal Code also does not include a legal provision for pre-arrest bail, which is recognized under international law. As a result, even in ordinary disputes, individuals are arrested, and there appears to be significant misuse of arrest authority by investigating officers. Emphasizing the need to reform the practice of detaining individuals in the name of investigation even when they may not ultimately receive a prison sentence, the report notes that “an excessive number of individuals are being detained during trial proceedings, and additional legal provisions are necessary to regulate detention hearings.”

The report emphasizes that except in cases where proceedings cannot occur without detention, trial should be conducted with bail or bond. It also recommends that the state introduce automated systems to monitor suspicious activities of individuals.

Another study has also recommended changes to detention practices. The National Judicial Academy, Nepal’s “Study Report on Legal Provisions and Practices Regarding Detention Hearings, 2080 BS” states: “Nepal’s prevailing practice of detaining first and hearing later appears contrary to established international human rights standards, the right to a fair hearing, and the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Nepal.” The report points out that in some cases, suspects are kept in detention throughout trial, but ultimately acquitted by the court. It raises the question: “After spending months or years in detention and being acquitted at the final stage of the hearing, how will the concerned individual evaluate the justice system? How will they be reintegrated into society?”

The report emphasizes that except in cases where proceedings cannot occur without detention, trial should be conducted with bail or bond. It also recommends that the state introduce automated systems to monitor suspicious activities of individuals. The report further states: “Even in non-bailable offenses, there is a lack of clear legal standards regarding the grounds required for detention, and in bailable offenses, there is insufficient legal guidance limiting the court’s discretionary power to deny bail. The law lacks clarity on additional conditions and restrictions based on the nature of the case.”

In its study, the National Judicial Academy, Nepal, particularly reviewed 240 detention orders issued in fiscal year 2021/22 in rape cases. Of these, 58 judgments were closely examined to recommend legal reforms. The report found that in most rape cases, courts ordered pretrial detention. However, in some instances, despite being detained, defendants were later acquitted at the time of final judgment.

Senior Advocate Shankar Kumar Shrestha argues that court orders must justify the necessity of detention. “The order must clearly state why detention is necessary. Its justification must be established,” he says. While he agrees that detention provisions may be appropriate in principle, he argues that courts often fail to clearly state the grounds and reasons for sending someone to pretrial detention. “The guiding principle seems to be – ‘detain first and investigate later,’” he says.

Former administrator Katuwal contends that individuals who are unlikely to abscond and who appear in court when summoned do not need to be held in pretrial detention. “Officials responsible for delivering justice must be impartial and independent. In similar types of cases, some are released for trial while others are detained. Decisions should not be based on influence or access,” he says.

Judicial precedents

Article 20 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to justice, states that “no person shall be detained without being informed of the grounds for arrest.” It also guarantees every person the right to a fair hearing by an independent, impartial, and competent court or judicial body. Article 21 provides for the rights of crime victims, stating: “A victim of crime shall have the right to receive information about the investigation and proceedings of the case in which they are the victim.”

Sections 67 to 80 of the National Criminal Procedure Code, 2017 outline provisions regarding detention, release, bail, and bank guarantees. Similar provisions are also found in ten other existing laws, including the Arms and Ammunition Act, 2019 (1962), the Immigration Act, the Foreign Employment Act, the Money Laundering Prevention Act, and the Organized Crime Control Act.

The Supreme Court has also established precedents regarding pretrial detention. In a decision dated 27 September 2009, the Court stated: “Keeping someone in pretrial detention does not portray them as fully or finally guilty. It is only an interim measure. If such reasoning were taken to its extreme, even the period of police custody during investigation would have to be considered illegal. If detention hearings were entirely prohibited, the investigation process in any criminal case could not be conducted.”

In some cases, courts have linked arrest and detention with the protection of personal liberty. In the government case against cricketer Sandeep Lamichhane, the Patan High Court, in its order of 12 January 2023, stated: “The general understanding that investigation begins only after arrest, along with the extremely limited, brief, and inadequate legal framework regarding bail and bond, has affected not only the personal liberty of the accused but also the victim’s right to justice.” Although the district court had ordered Lamichhane’s pretrial detention, the high court released him on bail. He was later acquitted.