Monitoring and action exist on paper, but consumers’ health continues to be gambled with in the market

KATHMANDU: On 11 December 2025, a team from the Department of Food Technology and Quality Control (DFTQC), while conducting market monitoring, found croissants produced by Nanglo Bakery to be harmful to health. After collecting samples and testing them in the laboratory, an excessive amount of trans-fat was found in Nanglo’s batch number 1 croissants.

The trans-fat related standard formulated by the department last year (FY 2024/25), stipulates that food items must not contain more than 0.2 grams of trans-fat per 100 grams of fat. However, the level of trans-fat found in Nanglo’s croissants exceeded this limit.

Trans-fat, which is artificially produced by adding hydrogen gas to liquid vegetable oil through industrial processes, is considered highly harmful to health. Trans-fat is commonly found in fried and baked processed foods.

Excessive consumption of such food increases bad cholesterol and reduces good cholesterol in the body, thereby raising the risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes.

For this reason, the use of trans-fat in food items is considered tantamount to a crime, says DFTQC Spokesperson Balkumari Sharma. She states, “We directed the Nanglo company to recall all croissants of that batch from the market, issue a public notice, and stop their sale and distribution.”

The trans-fat standard also mandates that the amount of trans fat must be clearly stated on food labels. However, DFTQC Spokesperson Sharma says such information is not found on all packaged food products available in the market. The World Health Organization had recommended eliminating industrially produced trans-fat worldwide by December 2023, but this has not been implemented.

Earlier, on 9 December, after quality issues were found in Khajuri Puff produced by Khajuri Nepal Pvt. Ltd., the department had instructed the company to immediately recall the product from the market. After excessive trans-fat was detected, the sale of puff products of batch numbers BI–3A and BI–5A was ordered to be stopped.

Similarly, the quality of Chickmas Mix Masala Powder was found to be substandard. When samples collected by the department’s monitoring team were tested, the total ash content in the masala was found to be 10 percent higher than the prescribed limit.

As it posed a direct risk to consumers’ health, the department instructed the importing company, MS Ruchika Trade Pvt. Ltd., to withdraw the product from the market.

Milk has also been found to be of substandard quality during the department’s monitoring. According to Spokesperson Sharma, due attention was not paid to quality from milk collection to sale. Instead of collecting milk in aluminum containers as required, it was found to be transported in ordinary plastic containers.

Milk collected with such quality compromises was also not stored at the proper temperature during sale. While milk should be sold after being stored at four degrees Celsius, it was commonly found being sold in baskets at dairies and shops.

“When the temperature is higher, the quality of milk deteriorates, and consumers are forced to consume such milk,” Sharma says.

The examples above are only some of the shortcomings found in a few products monitored and tested by the DFTQC team. There is no accounting of how many substandard and unhealthy products consumers are consuming among the many that the department’s team has not reached or examined. This is because government agencies, citing limited resources and manpower, do not conduct regular and comprehensive market monitoring. Even when shortcomings are found in products, strict action is not taken. As a result, market monitoring has failed to effectively compel industrialists and traders to improve the quality of their products. While substandard and health-harming food items continue to be sold freely in the market, public health is being seriously compromised.

Although the department publishes daily details of actions taken, the market does not appear to show concern for improving quality. The open sale of contaminated and substandard bottled water, pesticide-laden vegetables, and unhygienic meat are clear examples of this. Consumers may drink bottled water with confidence, but various studies have shown that producers are negligent in the production and distribution of such water.

Studies and tests conducted from time to time by bodies such as the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST) and the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division under the Department of Health Services have repeatedly revealed facts showing that jar and bottled water are unsafe and that fecal bacteria have been found in jar water.

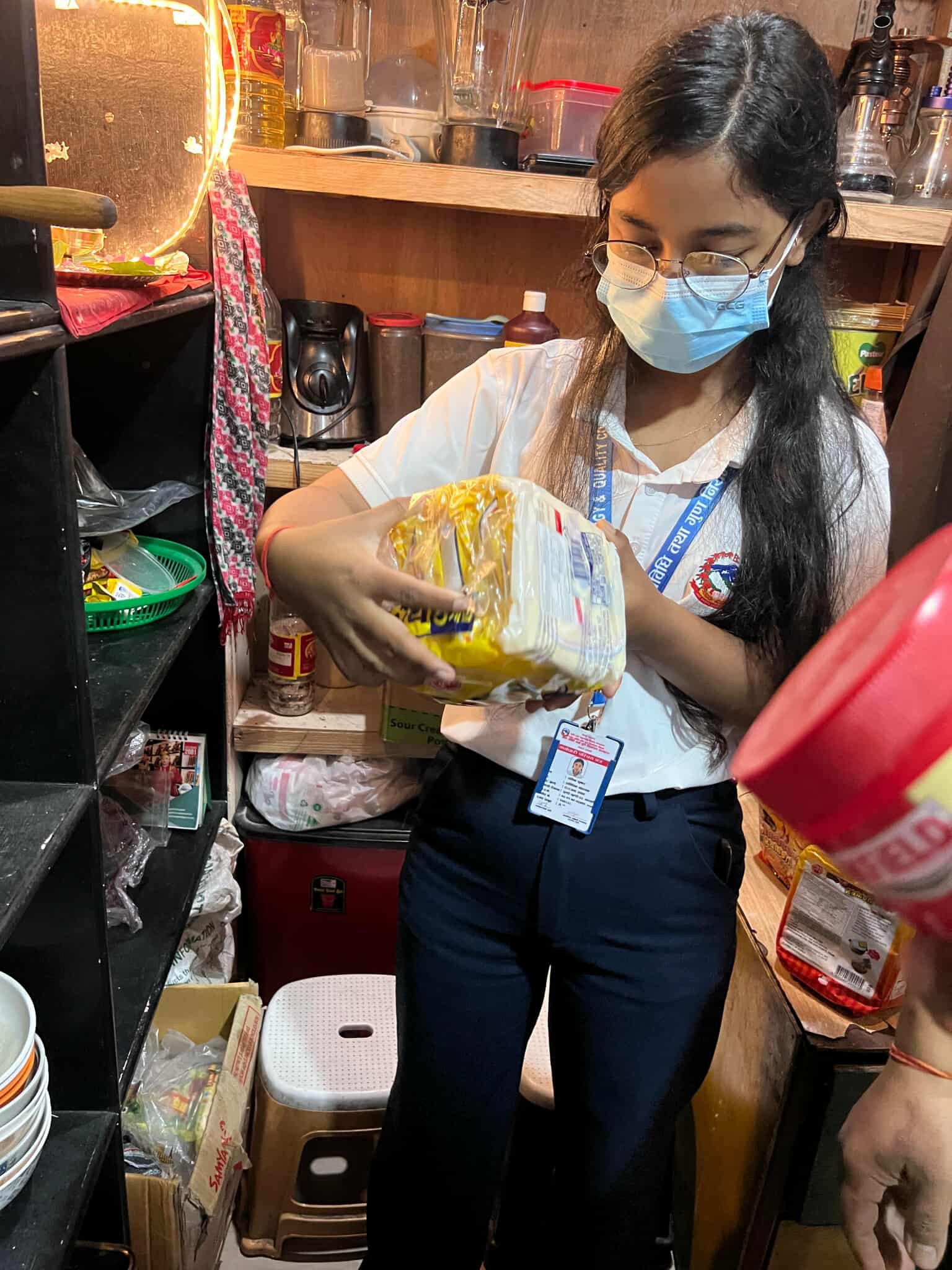

Employees of the Department of Food Technology and Quality Control conducting monitoring activities.

Consumer rights activist Jyoti Baniya questions the effectiveness of market monitoring, delays in reporting by government laboratories, and the effectiveness of testing at border points as reasons behind the lack of quality in food products available in the market. He says, “Traders tend to see market monitoring not as an opportunity to improve quality but as a tool of intimidation. That is why such mistakes keep recurring.”

Baniya also says it is hard to trust whether products ordered to be recalled by producers due to quality issues are actually completely removed from the market.

Will the new Food Act improve quality?

To ensure the cleanliness and quality of food items and protect consumer interests, the Food Hygiene and Quality Act, 2024 has been in implementation since 13 August 2024. Replacing the old Food Act, 2023, this act assigns responsibility for food hygiene at every stage—from primary production to processing, transportation, storage, and sale. The act also provides for legal action if the prescribed responsibilities are not fulfilled.

Section 33(1) of the act grants the Director General of the Department of Food Technology and Quality Control the authority to order the immediate recall of contaminated or substandard food items from the market.

Under the old Food Act, contaminated and substandard products were placed in the same category, which made it difficult to easily prosecute cases where quality shortcomings were found or where traders failed to fulfill their responsibilities.

The new act, however, provides for penalties ranging from heavy fines to imprisonment depending on the nature of the offense.

The new act also provides for on-the-spot fines of up to Rs 20,000, in the presence of the local administration, for traders who obstruct inspection and monitoring. For further action, samples of the product are tested; if substandard quality is found, cases are filed at the District Administration Office. If the product is contaminated, cases are filed in the District Court.

The act also requires traders themselves to issue a public notice, recall substandard products from the market, and destroy them. This provision aims to provide accurate information to consumers and make traders more accountable.

Consumer rights activist Baniya says that although the new act appears strong, he doubts its implementation. He says consumers’ health cannot be protected unless there is effective enforcement of the act, monitoring free from political pressure, a robust testing system, and equal treatment of all traders. “Food safety is directly linked to citizens’ lives, so the government must prioritize it,” he says. “The act aims to discourage traders from wrongdoing and ensure fair competition in the market, but its impact will be felt only if these provisions are fully implemented.”

DFTQC Spokesperson Sharma acknowledges that it is difficult to conduct nationwide and regular market monitoring due to limited resources. According to her, mobile lab vans used for on-site testing have enabled immediate testing of pesticides, oil quality, and food coloring.

“This has helped make traders more cautious and raise consumer awareness, but the limited number of vans makes it challenging to conduct regular monitoring across the country,” she says. “Although there are plans to collaborate with private laboratories and upgrade local-level laboratories, these have not been fully implemented.”