With Dalit women at its center, 'Shakti' establishes empowerment and defiance as its core, challenging societal and legal barriers

KATHMANDU: Eyes fixed in quiet contemplation, imagining a hopeful future while held in the embrace of a lover, an American citizen, in the calm of a riverside beneath the hills. Eyes that gleam with joy at the moment of marriage. Eyes that soften into a smile when gazing at a newborn child. And finally, eyes clouded with grief as the husband walks away, leaving her and their daughter behind forever.

These eyes belong to Durga, played by actress Laxmi Bardewa, the lead character of Shakti. In the film’s opening, there is no dialogue except her eyes. Through their shifting emotions, the narrative quietly takes shape.

In a later scene, Durga is seen mopping the floor of a hospital. A television plays in the background, broadcasting voices raised against violence toward women. At first, she flinches, but as the message turns to justice and resistance, her gaze steadies, fixed intently on the screen. In that lingering look, the film reveals its core: a story rooted in untouchability, gendered violence, and the struggle for dignity and change.

Nine-year-old daughter Lila, played by Polina Oli, and elder sister Maya, who is played by Menuka Pradhan, are Durga’s whole world in the movie. She receives all news of her daughter through her sister. Reaching home tired from the hospital duty, she asks about her daughter’s well-being while smoking a cigarette with Maya. Sitting and stroking past wounds, she is weighed down by the responsibility of raising a daughter. Nevertheless, her life is catching a rhythm in the company of her sister Maya and her daughter.

This rhythm breaks after Lila, who loves to draw, is enrolled in an art school near the house. The art school teacher initially teaches Lila to draw a bird spreading its wings. While Lila is learning to make the bird’s wings, she feels as if her own feathers are being clipped after the teacher starts touching her body indiscriminately. Before that, Lila, who appeared playful and unrestrained, could not tell anyone about her problem even if she wanted to. Durga and Maya feel the change in their daughter’s nature but do not know the reason. The more distracted Durga and Maya become to find the reason for Lila’s silence.

Actors Polina Oli and Akash Nepali featured in a scene from the movie. Photo courtesy: ARRI/Facebook

When Lila develops a fever, Durga first takes her to a doctor (Jiwan Bhattarai) and later to a Mata (Sarita Giri). It is the Mata who ultimately discloses the cause of Lila’s illness. The moment raises an unsettling question: was superstition necessary to uncover a truth that society itself refuses to confront?

After the ritual consultation, Durga and Lila walk home drenched in rain. In the following scene, Durga stands near a fire, steam rising from a pan and an evocative image of her suffocating inner turmoil. Across the room, Maya sits silently, holding Lila tightly in her arms.

The film’s first movement firmly establishes the psychological trauma of sexual abuse. From there, the narrative shifts toward resistance and the pursuit of justice.

The scene where Durga verbally lashes out at the teacher who abused her daughter is powerful. Lila’s teacher calls Durga ‘Kamini’ (a derogatory caste-based slur) in return. The teacher’s reaction serves as a reminder of the self-given right of non-Dalits to use insulting and contemptuous language against Dalit women.

Maya herself is traumatized by the incident Lila faced. She reveals that, like Lila, she too was a victim of sexual violence in the past. At this time, Durga and Maya, seen in the same frame, look at each other in silence. The intergenerational experience of both mother and daughter being tormented by sexual violence makes the core subject of the film even tighter.

In the process of seeking legal remedy, Durga faces one legal hurdle after another. She faces humiliation. In such cases, the Dalit community, which is at the bottom in terms of caste, becomes even more tormented. The structure of double oppression of caste and gender discrimination makes Dalit women even weaker. However, the objective of the film Shakti is not to show the characters of the oppressed community as weak as in other films. Durga’s refusal to conceal her caste identity as she resists and speaks out is the film’s greatest strength.

“Shakti,” meaning “power” and “strength” in Nepali, is a multi-meaning name that writer/director Nani Sahra Walker has used consciously. In this, there is a fight between those deprived of power and those who misuse power. This fight has raised the question of in whose hands real power lies in society. Because of these characteristics in the film, Shakti was successful in winning the Jury Mention Award at the 13th Nepal International Human Rights Film Festival.

Menuka Pradhan and Polina Oli

In the film, filmed in places including Kirtipur and Lalitpur, an attempt has also been made to establish the spiritual aspect of the Valley as a form of power. Places like Pashupatinath and Swayambhu have fallen under the director’s priority to show Hindu and Buddhist religious sites and the activities that take place there. Religious and tourist spots have been chosen for filming. Scenes of worshiping are repeated. Whether it is the Aarti of Pashupati or the procession of monks, it is felt that the context of some scenes could not be established. It feels as if the director has viewed these locations through ‘tourists’ eyes.’

The film’s central aim is to affirm and foreground female strength. Even the names of its main characters, which are Durga, Lila, and Maya, evoke forms of power. At one point, the character Mata tells Lila, “There is power within you, child,” reinforcing the film’s enduring message that strength resides within women themselves.

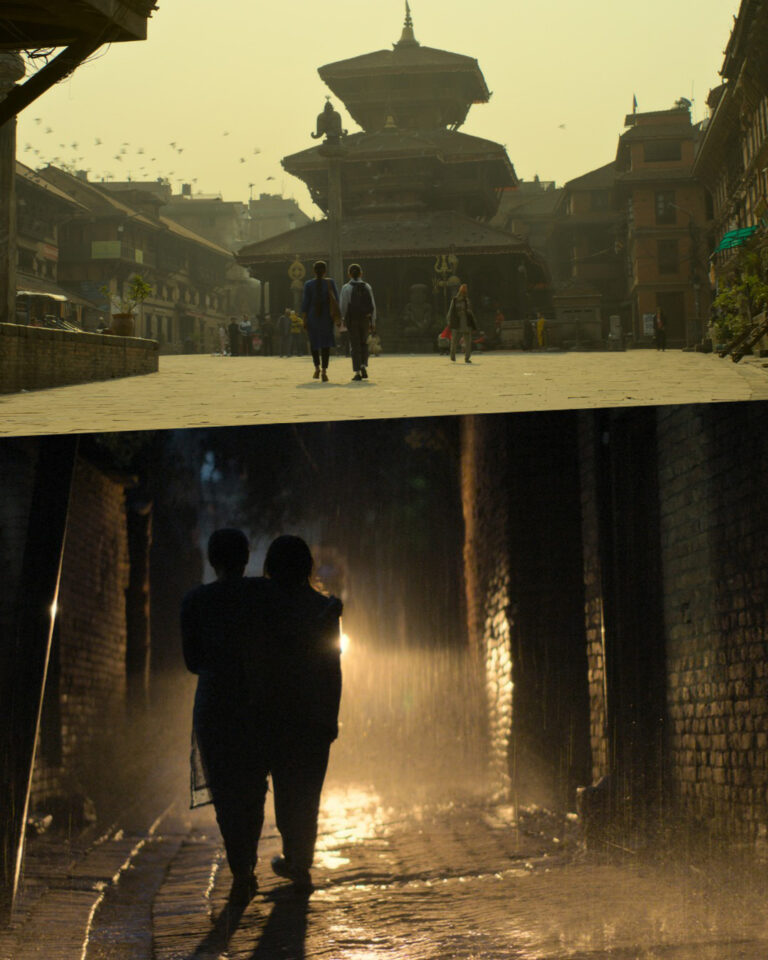

Two featured stills from the film ‘Shakti’

To bring alive characters struggling with mental internal conflict, the acting of lead actors Laxmi, Menuka, and Polina has done important work. The acting of Sarita Giri, the teacher’s father Prakash Ghimire, teacher Akash Nepali, Doctor Bhattarai, and teacher Srishti Shrestha, among others, is also well suited to their characters.

At the time this film was being made, Nepal’s law imposed a statute of limitations of just 35 days for filing complaints in cases of sexual abuse. The film highlights how this restrictive deadline itself became a major obstacle for survivors seeking justice in deeply sensitive cases of sexual violence. It portrays the layered structures of oppression, such as social, emotional, and legal, that compound the suffering of victims.

Before the film’s release, the statute of limitations was extended to two years. However, voices continue to demand its complete removal. Director Walker also supports abolishing the limitation entirely.

In the broader evolution of cinema, two dominant tendencies can be observed. One distances oneself from reality and reinforces dominant narratives, while the other confronts uncomfortable truths and challenges established norms. Shakti belongs to the latter. Its purpose is to transform the struggles of marginalized characters into a form of social consciousness.

Director Nani Sahra Walker accepting the award for the film ‘Shakti.’ Photo Courtesy: Nepal International Human Rights Film Festival

Director Walker uses the themes of caste, gender, and legal processes as tools to spark public dialogue. Films like Shakti draw from real events and invite not only emotional engagement but also critical reflection from the audience. This, too, is the film’s appeal.

With a narrative led largely by women, Shakti tells a story that is deliberately unsettling. Just as the film centers on layered marginalization, Dalit women remain at its core. Not only the characters on screen but also several of the actors and creators come from this background, inviting reflection on the relationship between representation on screen and lived reality beyond it.

The film begins with the expressive gaze of Durga and ultimately returns to it. In the final moments, her eyes turn toward the audience, breaking the fourth wall. As Dimitri’s closing rap song Naam plays, its lyrics sharpen the film’s final provocation. Speaking of violence, division, and an unbroken search for justice, the song builds to a piercing question:

“This is the search for justice

I feel the warmth of a journey of violence

Only the blood of the divisionists

Inside the cool jungle, my soul

Let me dip into your water

But I still have humanity in me

Due to my patience

Is it in the law or the cage?”

The screen fades, but the question lingers long after the film ends.