Born in Tibet, raised in Kathmandu and spread around the world

KATHMANDU: These days, the social media feeds of Gen Z or urban millennials say that Kathmandu is the city of momo. Every day, they are sharing pictures/videos of various kinds of momo in a mouth-watering way and saying, ‘Momo is not just a taste; it is an emotion.’

The Nepalis’ fondness for momo seems it does not only go inside our stomach; its taste is etched and stuck in the soul. In Kathmandu Valley’s old narrow alleys, new wide roads, small eateries without a name, and huge one- or two-star restaurants, thousands of people are simultaneously intoxicated by the smell of hot momo steam. While eating momo with the sour and spicy taste of the achar (a spicy and tangy dipping sauce served with momo), they are proclaiming, ‘The only snack is momo.’

For many, the world’s best momo can only be found in Kathmandu, a city where its culinary variety is unrivaled. This passion for momo isn’t confined to Nepal; it has become a staple for Nepalis everywhere, ensuring that a taste of home is present in communities across the globe.

It might surprise many to learn that momo wasn’t always a staple in Nepal. While it’s now an integral part of Nepali cuisine, it only gained widespread popularity in the last two decades, having first entered the public culinary scene around the 1950s.

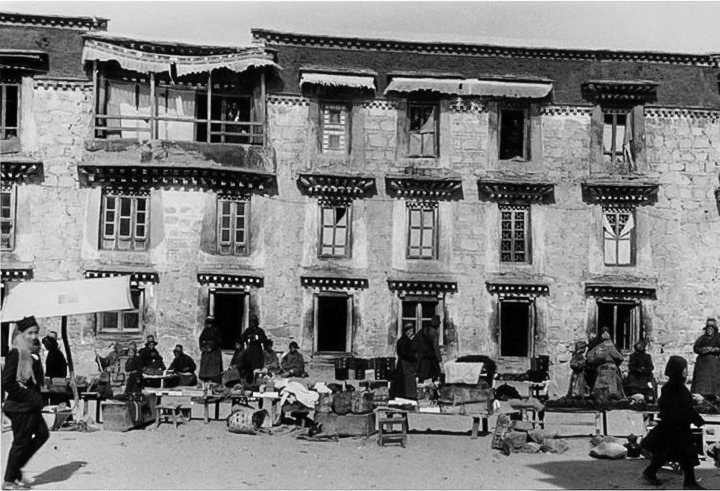

The story of momo and Nepalis is rooted in a long history of cross-border trade. The Newar community of Kathmandu served as a central link for commerce between India and Tibet. According to an article by Pitamber Sharma in the book Saharikan: Jibikako Bibidha Aayam, the cities of the Kathmandu Valley dominated the Tibetan trade from 1480 to 1768. This lucrative business led many Newars to travel to and from Tibet, with some establishing permanent homes there.

At that time, Kathmandu had a monopoly on the route for Tibetan trade with India. The Newars who received special privileges to do business there had established their dominance. In a book called Bhikshu, Byapar ra Bidroha, journalist Sudheer Sharma has mentioned that there were Nepali shops in Lhasa that were more than five hundred years old. The same Lhasa-Newars also opened the Nepali Chamber of Commerce in Lhasa in 1943. Newar traders used to bring expensive goods from India and sell them to rich families in Lhasa. For this, they had to make a very long and difficult journey. Even today, the descendants of those who did business in Lhasa are called Lhasa-Newars, Lhasa-Sahu.

Newar traders who lived in Tibet for years were naturally influenced by the local food culture there. Under this influence, out of desire and compulsion, they also learned the skill of making the local food. It can be estimated that those same traders returned to Nepal and taught their family members how to make those dishes.

Customers enjoying momo at Narayan Dai Ko Masang Galli Ko Momo Shop/ Photo: Bikram Rai/ Nepal News

Kathmandu is a city where people are free to eat whatever they want in restaurants, but even inside homes, some foods are still forbidden. Because momo was a street snack, not only non-Newars within the Newar community but also Newars of “high class and high caste” were hesitant.

Historians go to the history of Chinese dumplings, which are called ‘Jiaozi’, to understand the history of momo. Dumplings are a ball of refined flour/flour that is steamed in the steam of boiling water. Many conclude that the Chinese dumpling became ‘mog mog’ when it arrived in Tibet. Tibetan mog mog had meat and a little vegetable, but no spices. The meat was also yak or sheep. The Lhasa-Newars “Newarized” the mog mog by using buffalo meat and spices in Kathmandu. And they gave it their own name, momocha.

Kashish Das Shrestha, who is currently writing a book focusing on the history, development, and future of momo, considers the Lhasa-Newars to be the masterminds behind bringing momo to Kathmandu. He says, referring to some articles that write a fictional story that momo went from Nepal to Tibet in the 14th century, “There is no basis for arguing that momo entered Nepal via the route of Tibet.”

Kashish argues that momo was never a part of the traditional food in the kitchens of Kathmandu’s Newars. “In the Newar culture, which has a food tradition of hundreds of years, momo was added later as a new dish,” he adds. “Momo, which was limited to Guthis (a traditional social and land trust system of the Newar community that organizes members to manage rituals and preserve cultural heritage) or family activities from the end of the 1800s to the 1950s, slowly began to become a commercial dish after that.”

This is also the reason why momo appears in the public memory of Nepalis only around 1940/50. Kamal Ratna Tuladhar, the author of the book Caravan to Lhasa: A Merchant of Kathmandu in Traditional Tibet, has shared a memory of seeing a momo shop for the first time on the roadside in Kathmandu around 1942. Before momo entered the market of Kathmandu, it was only cooked in the homes of these wealthy Lhasa-Newars.

Momo only appeared in the public consciousness of Nepalis around 1940/50. In a book, Caravan to Lhasa: A Merchant of Kathmandu in Traditional Tibet, author Kamal Ratna Tuladhar recalls seeing a momo shop for the first time on a Kathmandu roadside in 1942. This was a significant shift, as before this, momo was exclusively cooked in the homes of the wealthy Lhasa-Newars.

And momo became momocha

Mahendra Man Shakya of Patan is one of the few who had the privilege of tasting momo at home at that time. His father, Tej Man Shakya, arrived in Lhasa at the age of 13 in 1930, and lived there for a few years doing business. In Mahendra’s memory, momo was cooked at his house once a month on a Saturday, and that day was like a festival. Perhaps because of that attraction for momo from that time, he is still in the momo business today.

Old and traditional momo shops in the Kathmandu Valley/ Photo Credit: Social Media

Until democracy came in 1950, the tradition of eating out had not been established in Kathmandu. The book Nepal in the Long 1950s, published by Martin Chautari, contains an article about the history of Tilauri Maila’s tea shop by Prabas Gautam. According to the article, there were only a few snack shops in Kathmandu until 1951, most of which were traditional confectionary shops and local eateries. Confectionary shops were only retail shops selling sweets and there was no arrangement for sitting or talking there, whereas local eateries were open only to limited customers.

In the old settlements of Kathmandu, such as Asan, Indrachowk, Basantapur, and New Road areas, snacks like peas, chickpeas, soybeans with barbecue, or boiled potatoes, lentil patties, sweet potatoes, chatamari, and selroti, among others were kept for sale. In the evening, near Tundikhel, ice cream and other snacks were sold targeting football players. Since the area where momo was commercially sold started from New Road to Asan, momo also got mixed with these dishes later. Still, there were few places to get momo, and few people would eat it.

In human migration, not only do people walk, but language and food culture also walk with them like a shadow. The momo pot also accompanied them like a shadow. If language and food survive, civilization survives. Whether it was for labor, education, or earning money, every Nepali’s tongue sought Nepali taste, no matter which part of the world they went to. Wherever Nepalis gathered abroad for get-togethers, feasts, and festivals, momo became their shared taste.

There were a few anonymous tavarn that could be called hotels. One of the old names among the momo shops with a name is Natikaji Ko Momo Shop. This shop, which was around 1950, and then Narayan Dai Ko Famous Momo of Masang Galli in 1962 and RC Momo, which has been in operation since 1966, are important. Many people believe that momo made a commercial leap after RC Momo opened in front of Ranjana Cinema Hall. The famous artist Madan Krishna Shrestha has also mentioned this shop, run by Ram Krishna Shrestha and Chaita Narayan Manandhar, in his autobiography Maha Ko Ma.

Madan Krishna once lived at the house of Ram Krishna, the owner of RC Momo, in Bhote Bahal. He has written, ‘At that time, Ram Krishna was probably the first person to honor momo, which used to be sold on a tray by the roadside, by running a restaurant with chairs and tables. He even hung a large signboard with the name RC Momocha Restaurant in front of the shop.’

Photo: Bikram Rai/ Nepal News

Before opening the restaurant, momo cooked on a small stove by the roadside was sold on a leaf plate. Ram Krishna, the owner of RC, was also one of those who sold momo in this way. ‘Before opening the RC restaurant, I also saw Ram Krishna selling momo in the same way on a tray outside the main gate of Janasewa Cinema Hall and Ranjana Cinema Hall,’ is mentioned in Madan Krishna’s book.

When the old generation of Kathmandu remembers the first place they ate momo, the names of Ranjana Cinema Hall, Bishwajyoti Cinema Hall, Janasewa Cinema Hall, and Jai Nepal Cinema Hall come up. After momo started being sold on the streets, in alleys, and outside movie halls, the number of people eating momo increased. Momo businessmen themselves admit that momo’s popularity took a leap after the success of RC Momo. One of them is Gopal Kakshapati, the owner of Nanglo Bakery. He says, “RC opened a restaurant and brought momo, which was limited to street food, to a wider group.”

After that, Indira Momo, Jharana, Everest, Shandar, and Nanglo, among others, played a role in the expansion of momo. Momo reached the main intersections like Mahabuddha, Dharahara, Jamal, Dharmapath, Buspark, and Chabahil. It also spread to places like Krishna Mandir, Lagankhel Buspark in Patan, and Bhaktapur Buspark. Among the old momo shops in Patan, KD Momo in Mangal Bazar is also notable.

Momo is a dish that was born in Tibet and grew up in Kathmandu. Although its origin is China/Tibet, the Lhasa-Newars “Newarized” the momo. In Kathmandu, buffalo meat was used instead of yak meat. The Tibetan momo was large in size. It had a lot of onions and vegetables too. The Newar community gave more importance to chhyapi (spring onions) than onions. In Tibet, soup was the friend of momo, but in Kathmandu, achar became its friend. Spices were added. Festivals and food according to the season are a specialty of Newar civilization. Momo also became a part of Newar Guthis and festivals. The practice of eating hot momo in cold weather also developed in this way.

Various non-Newar ethnic groups, languages, and people from different regions have come and mingled with the Newari culture. They adopted the Newari dishes in the same way. But in a society where religious and social untouchability was deeply rooted, buffalo momo was limited to the Newar diet for a long time. It is not that there were no Brahmins and Chhetris who would secretly eat the buffalo meat lump hidden inside the flour. The artist Madan Krishna has written that RC Momo made a great contribution to this, ‘That must have been the shop that introduced buffalo meat to many Brahmin brothers in Kathmandu at that time. Not just ‘must have been,’ it wouldn’t be wrong to say that it was.’

Kathmandu is a city where people are free to eat anything in restaurants, but those foods are still forbidden inside homes. Because momo was a street snack, not only non-Newars within the Newar community but also Newars of “high class and high caste” were hesitant. Kakshapati says, “Among Newars too, the ‘Kasangkar’ (Newars with business ties to Tibet) would eat a lot. It was not a food that was accepted by everyone within the Newar community.”

Executive committee of the Nepal Chamber of Commerce, Lhasa, in 1947/ Photo Credit: Facebook page ‘Lhasa Newar: Nepalese Traders’

On one hand, because of buffalo meat, and on the other hand, because it was a street snack, a large segment of society was left out of momo. As long as it was a food of a specific group and class, momo was in a shrunken, looked-down-upon state. Feeling this situation, Nanglo, which opened in 1976, introduced chicken momo to its menu around 1985. Then, veg momo was also added, and then mutton momo. Then, customers from other communities like Brahmins and Chhetris, who had been left out, joined in.

“Customers could eat momo with or without the meat they liked. After that, no one was left to reject momo,” says Kakshapati, “After it started being sold as a prestigious food at a nice table, the middle class and even the upper class accepted momo, even if it meant paying a little more. Tourists also tasted the momo.”

The global journey of momo is not the result of one person’s desire or interest. Just as a person who goes to a new place becomes a little bit of that place and the rest remains the same, momo is the same. Wherever it goes, it can mix and change, but in its essence, it does not lose its original taste.

He remembers that when momo was brought from a footpath snack to the menu of an expensive restaurant, he had to endure negative comments at that time. Many said, “Such a luxurious restaurant selling that kind of footpath food?”

But many customers who got to eat momo in the comfortable atmosphere of a restaurant rather than on the street appreciated it. The negative comments disappeared. After that, it became mandatory to include momo on the menus of modern and expensive restaurants. Today, a menu without momo is rare. Momo has spread from five-star hotels to local eateries. This is the stage where momo, no longer limited to the Newari snack, started to become a Nepali dish. The name of Jharana Momo of old Dharahara, which attracted even the indigenous Brahmins/Chhetris and government employees here by selling mutton momo in Kathmandu, is also worth remembering.

Momo, which is cheap and easily available, is not only tasty, but also filling. The fact that it can be had at any time, whether for breakfast, lunch, or dinner, is its specialty. What more could a non-vegetarian want when they can also eat meat! That too, chicken, mutton, and pork by choice. For vegetarians too, options like paneer and cheese. Momo, which is as useful as dal-bhat (native Nepali meal), was not meant to stay confined to Kathmandu.

On the other hand, momo had already reached some places in India, including Darjeeling, which had commercial ties with Tibet, just like Kathmandu Valley. Wherever Newar traders settled, they spread momo. Due to the connection with Darjeeling, a momo shop had already opened in Dharan, Nepal around 1961/62.

Amish Raj Mulmi has mentioned in his article that after the Tibetan rebellion of 1959 and the exile of the Dalai Lama, when Tibetan refugees came to India, momo spread to refugee camps from Majnu Ka Tilla in Delhi to Bylakuppe in Karnataka.

King Mahendra welcomed with momo by members of the then Newar Business Committee during his visit to Kalimpong, India in 1953/ Photo Credit: Facebook page ‘Lhasa Newar: Nepalese Traders’

Kashish considers the 1980s/1990s to be the time when the expansion of momo within the country reached its peak. The network of momo shops with the same name and brand is one of the reasons for this. There are also plenty of momo chains in Kathmandu that have been in operation for 40 years and carry on a family legacy, whose names have already become brands. Some of these brand chains are also expanding to cities outside Kathmandu. They have shared different tastes, styles, and experiences with customers. Somewhere a traditional taste, somewhere a taste with new experiments. Some on a sal leaf platter, some on a plate.

Everest Momo, New Everest Momo, Baglamukhi Momo, Dharahara Momo, Kiran Dai Ko Momo, Narayan Dai Ko Famous Momo of Masang Galli, Five Star Momo, Momo Mantra, Momo Magic, Om Momo, Thule Dai Ko Tapari Momo of Lalitpur, Momo King, Bishal Momo, Shikhar Momo, Classic Momo, Shandar Momo, Nice Momo, Dalle Momo, and Darjeeling Momo, among others, are some of the popular momo shops. Besides these, momo is also widely consumed in big hotels like Nanglo, Hotel Annapurna, Dwarika’s, Radisson, Shangri-La, and Hyatt. In normal restaurants or stalls, the price per plate is seen to be from Rs 130 to Rs 300. The price in inexpensive hotels is from Rs 400 to Rs 1,000. On average, popular momo shops sell 500 to 1,000 plates of momo daily.

Representative of Nepali Taste

Just as coriander is used a lot in our kitchen, minari is used a lot in Korean kitchens. It is a plant that spreads quickly when it gets water. This plant grows slowly in the first year and grows fast in the second year. In the movie Minari, which depicts the struggle of Korean immigrants, it is used as a Korean symbol that connects the immigrant characters of Minari to their country. The character of Nepali momo is also like the Korean Minari. On foreign soil, momo is such a symbol, which is connecting Nepalis with their country and culture. Momo, inside and outside the country, is spreading at a faster rate in the second year than in the first year, just like minari.

Kashish says that the journey of momo’s expansion has reached a very interesting point in many countries of the world. According to him, its popularity in Nepal has reached its highest point ever. Its expansion around the world is also the fastest it has ever been. The presence of Nepali momo is increasing in markets from the UK, Germany, Canada, Africa, Italy, France, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan to Russia.

Owner Krian Shrestha setting up his shop at Kiran Dai Ko Momo in Gyaneshwor/ Photo: Prabhakar Gautam/ Nepal News

Currently, its rate is even higher, especially in India and America. There is a wide participation of the Nepali community in momo stalls found on the streets of Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru, and in large-brand momo businesses. The Nepali identity of momo stalls run by Nepalis in India has become a symbol of ‘quality.’ Even some big brands in India, like Wow Momo and Prasuma Frozen Momo, are being led by Nepalis and are increasing the dominance of the Nepali taste. Wow Momo, which was started by Binod Humagain from Kavre with his classmate Sagar Daryani, was started by renting a small shop in Kolkata. Wow Momo, which started in 2008 with INR 30,000, has reached about two hundred outlets in India. It is being established as the number one momo brand in most major cities. The owner of another big brand in India, Prasuma (Frozen Momo), is also from the Nepali community.

Himalayan Yak, the first momo restaurant to open in Queens, New York; Juju Momo in Boston, Massachusetts; and Bhansaghar in Utah are just examples of Nepali momo expansion abroad. There are more than 50 Nepali momo stalls in New York alone, and momo can be found in every state of America. Because some Indian restaurants have Nepali chefs, Nepali-tasting momo can be found.

Kashish Das Shrestha, who is currently writing a book focusing on the history, development, and future of momo, considers the Lhasa-Newars to be the masterminds behind bringing momo to Kathmandu. He says, referring to some articles that write a fictional story that Momo went from Nepal to Tibet in the 14th century, “There is no basis for arguing that Momo entered Nepal via the route of Tibet.”

Food festivals in America have contributed to the promotion of momo. The Momo Crawl in New York and the Momo Festival in Texas are examples of this. Since the 1990s, Nepali students studying in America and other countries have been making and presenting momo at college-level international food festivals and other events. These days, special festivals are being celebrated. More than 3,500 people participate in the Momo Crawl in New York, where non-Nepalis are in the majority. The Momo Festival in Texas has the participation of more than 10,000 people, where Nepalis are in the majority. Kashish says, “This was not possible until 2015.”

Wow! Momo in India/ Photo Credit: Facebook page ‘Wow! Momo’

In Hong Kong, where there is a large presence of Nepalis due to the settlement of Gurkha soldier families, places to eat momo are found everywhere in places like Jordan and Yuen Long. Artist Sujata Gurung, who grew up in Hong Kong, says that momo can be found in almost every restaurant there. According to her, Jordan’s Chatpate House is famous for takeaways. Sujata’s experience is that whenever there is an excuse for leisure, a holiday, or a festival, Nepalis in Hong Kong make and eat momo at home. Now living in Kathmandu, she says, “I am in Nepal now, but when I talk to my sister in Hong Kong, we keep talking about momo. She ate Jhol momo at a newly opened Newari Lakhe restaurant! She was saying it was very delicious.” Sujata is missing the momo her sister made at home in Hong Kong and the two or three types of achar.

Whether it is the Dal Bhat restaurant in Berlin or the Chatpate House in Jordan, similar stories connected with momo are found everywhere. The famous singer of the band Kandara, Bivek Shrestha, who has spent more than a decade abroad in the UK and Australia, is now in Pokhara. He, who regularly eats momo with soup in Pokhara, used to miss momo a lot in his early days abroad. “Initially, there were few places to eat momo, so we would make it at home. The process of everyone getting together to make momo at home is like a festival. Slowly, momo started to become the main dish of every Nepali restaurant,” he recalls, “I feel that momo truly represents Nepali food on foreign soil. Momo has become an unofficial national food, and it has done the job of connecting Nepalis living abroad.” As he said, those who run Nepali restaurants are mostly introducing Nepal through momo.

After the political change of 1989, the number of Nepalis going abroad started to increase. After the Maoist armed conflict in 1995, the number of people migrating abroad increased sharply. In human migration, not only do people walk, but language and food culture also walk with them like a shadow. The momo pot also accompanied them like a shadow. If language and food survive, civilization survives. Whether it was for labor, education, or earning money, every Nepali’s tongue sought Nepali taste, no matter which part of the world they went to. Wherever Nepalis gathered abroad for get-togethers, feasts, and festivals, momo became their shared taste. Momo played a big role in saving them from homesickness. Whether it is New York or London. Whether they are Nepalis from Berlin, Sydney or Tokyo, they thought of momo, they looked for momo. Kashish, who is currently in America, says, “Wherever I go, I look for momo. I want to eat momo for lunch every day.”

Zuzu Momo in Boston, USA/Photo: Google Street View

Mahendra Man, who started the Momo King chain in Baneshwor in 1995, compares, “It’s something that many people didn’t think could happen, that momo could spread outside Kathmandu and all over South Asia. That it would reach America, Europe, and Africa is beyond imagination.” He is also excited to see the leap that momo has made in 25 years. He has just opened a new branch of Momo King behind Talaju Bhawan in Makhan Basantapur after Patan. He says, “I chose this place to introduce foreigners to Nepali heritage and monuments while feeding them momo.”

Just as a menu in almost all restaurants in Nepal is not without momo, the same was followed in restaurants run by Nepalis abroad. Some who live abroad are not only spreading the Nepali taste through momo in restaurants, but some have also made the promotion of momo their main campaign. One of them is Chef Binod Baral, who ran a typical Nepali restaurant Roti Momo in the UK. “Nepalis would put momo on the starter, I was the first to make it the main course and brand the momo. My restaurant used to have 55 varieties of momo.”

KFC on one side, burger-pizza hubs on the other, and Nepali momo in the middle. Momo in Australia is between McDonald’s and KFC. Chef Binod says what could be a more beautiful sight than this, branding Nepal on foreign soil among the world’s biggest brands. His book Momo ka Pilaharu was launched on July 3, 2025, in the UK Food Festival, and he has traveled around the country and abroad as a momo activist.

In this way, momo, with its spectacular presence on the world’s big platforms and immense potential, has provided a strong source of economy, employment and entrepreneurship. Kashish says, “There is no formal data on the momo economy, but there is no doubt that momo is the main basis of the Nepali restaurant economy. This is only a matter of formal trade, the informal economy is even bigger.” Momo is the gateway that introduces foreigners to Nepali food culture. It is very likely that foreigners, after getting used to the taste of momo, will move on to other foods. Therefore, momo can also be used in a planned manner as a medium to boost the overall food economy.

8848 Momo House in Melbourne, USA/ Photo: Google Street View

Momo’s contribution to the preservation of culture and identity is not small. Momo is not just a food of the market. Whether in the country or abroad, wherever there are Nepalis, there are momo parties at home. The process of gathering together, kneading the flour, rolling it, making the filling, making the dough balls, putting the momo on the steamer, and waiting eagerly for it to cook is socially important. It is during these times that there is a competition to see who can eat the most momo. In the process of socialization, it helps people to mingle.

The global journey of momo is not the result of one person’s desire or interest. Just as a person who goes to a new place becomes a little bit of that place and the rest remains the same, momo is the same. Wherever it goes, it can mix and change, but in its essence, it does not lose its original taste.

This is a journey of cultural fusion, in which Buddhist traditions and trade are mixed. Momo is a souvenir brought by the Newar community from the difficult and adventurous journey across the Himalayas. It is a token of friendship gained during the struggle for survival. In Jagat Birsingh Kansakar’s book Lhasa More Than a Hundred Years Ago (A Glimpse), the difficult journey to Lhasa is described. At that time, it would take almost a month to cross the Himalayan passes and dense forests to reach Lhasa. Some traders would leave their wives at home and even marry Tibetan girls there and settle down. There are plenty of social stories and sorrows of the Tibet trade in the folk literature of Nepal Bhasa. One of the popular parts of a song-story is like this:

Ji Waya La Lachhi Maduni (Not even a month has passed since I came)

This song-story, which is about two hundred years old, tells the story of the separation between a husband and wife when the husband goes to Lhasa (Tibet) for business. Laxmi Prasad Devkota’s famous tragic Muna Madan was influenced by this Ji Waya La Lachhi Maduni.

Newar traders at a business center in Lhasa in 1938/Photo: Facebook page ‘Lhasa Newar: Nepalese Traders’

The influence of momo transcends mere cuisine, inspiring not only traditional folk songs but also stories celebrating Nepali taste and skill. This tradition continues today, as the post-republican era has seen social media become a powerful new medium for sharing momo’s cultural story.

Momo’s journey has extended far beyond the kitchen. Thanks to social media influencers, the dish has traveled seamlessly from platforms like Instagram to TikTok, becoming a viral sensation. Social media has become the primary tool for enthusiasts to discover where to find and what kind of momo is available.

Leveraging social media and new technology, momo has successfully captivated the younger generation, who have in turn become dedicated fans. This phenomenon has seen momo featured in everything from vlogs, blogs, and memes to books.

The trend has gone global, with tourists from neighboring countries and distant lands creating momo-focused vlogs and shorts, widely proliferating across digital platforms. In the global promotion of Nepali momo, these digital materials have accomplished more in a single year than was possible in a decade of traditional methods.

Nepali Momo/ Photo: Bikram Rai/ Nepal News