KATHMANDU: While reviewing the 62nd report of the Auditor General, an intriguing detail was found in clause 124. It states that the capacity of electric vehicles imported through the Rasuwa and Tatopani customs offices had been reduced before verification and release.

The report further notes that the customs duty and taxes amounting to Rs 3.77 billion, which were exempted by those offices, must be investigated and recovered.

The attraction and availability of electric vehicles in Nepal are at their peak. The business of importing electric vehicles is also thriving. However, the fact that the state lost customs duty and taxes because the capacity of imported electric vehicles, especially Chinese ones, was reduced, naturally became a matter of concern for journalists.

To seek further details on this, I contacted Deputy Auditor General Ghanshyam Parajuli, who is the Chief of the Finance, Financial and Performance Audit Department of the Ministry of Finance. Since the auditing of the agencies under the Ministry of Finance was done under his leadership, he is one of the people who would have detailed information regarding the reduction of electric vehicle capacity and tax evasion.

However, Parajuli did not want to discuss the matter at all. He said, “We have sent the 700-page report to the Ministry of Finance. Please get the information from there.”

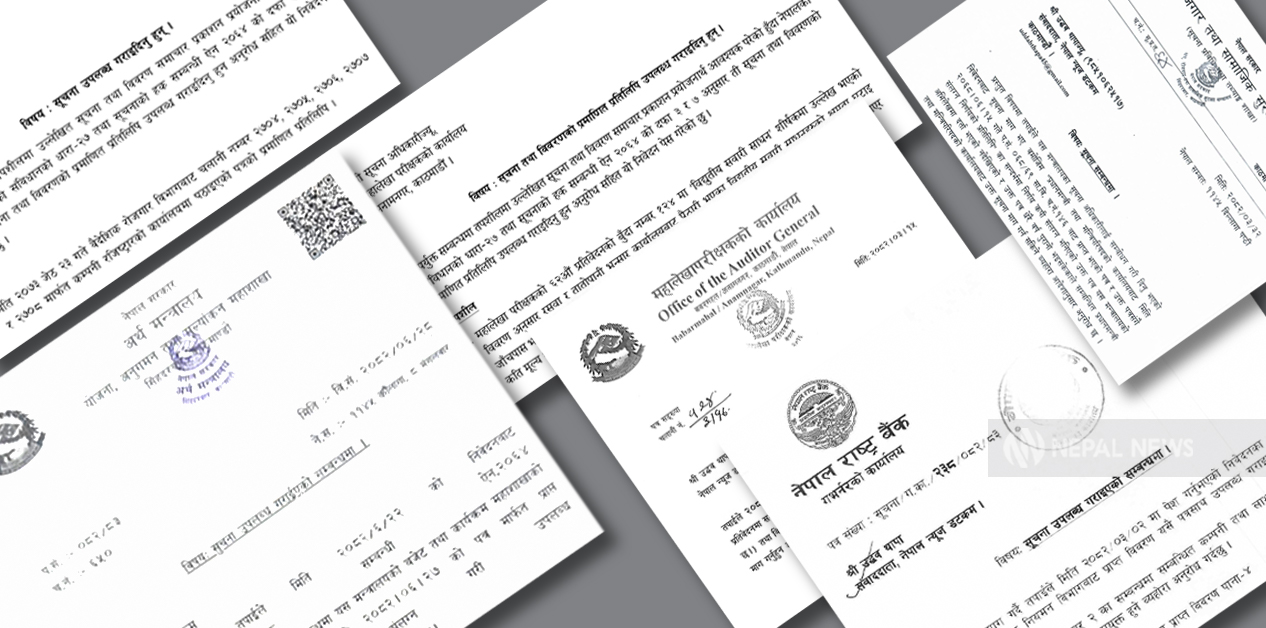

When it became clear that information would not come from him, I decided it was appropriate to use the constitutional provision related to the right to information as a citizen’s right and emailed an application on June 16, requesting information. In the application, I had requested, “Please provide detailed information on the subject mentioned in clause number 124.” I had also submitted an application requesting information on two other subjects. On June 16, I personally met Ramesh Subedi, the Information Officer of the Auditor General’s Office, and explained the seriousness and necessity of the information requested. In response, he said, “The role of the information officer is only to coordinate. You will get the information if the related division provides it.”

A written response arrived on June 29: “We request you to take the information you have requested, which is included in the 62nd Annual Report of the Auditor General (which is available on this office’s website), from that report, and to request the subjects included in the preliminary reports of various offices from the concerned offices.”

If the information in the report alone had been sufficient, there would have been no need to file an application requesting information.

By giving a perfunctory reply, the Auditor General’s Office shirked its responsibility to provide information.

Almost all government bodies hesitate to provide information to citizens. They are keen on trying not to give information if possible. Government bodies should be accountable and transparent to the public. Moreover, the Constitution itself has ensured the citizen’s right to information. There is the Right to Information Act – 2007. The Information Commission has been formed.

There is a provision for punishing officials who fail to provide information. The summation of all this is a transparent state system. However, government bodies have not fully embraced a system that is answerable and accountable to the public. Instead, the tendency among government bodies is to avoid giving information if possible, and if they cannot avoid it, to give incomplete information and walk away.

The Nepal Rastra Bank is another example of hesitation in providing information. I had received information that the number of inactive bank accounts in banks and financial institutions is continuously increasing, and the amount of money left behind by the account holders is equally large. In some banks, there was information that a single account holder had left behind millions of rupees.

The Nepal Rastra Bank is the only body that can provide consolidated information on how many accounts in banks and financial institutions are inactive and how much money the account holders have left behind. I met Rastra Bank officials with this query. However, they did not show any interest in providing this information.

I met Suman Neupane, the Information Officer of the Rastra Bank, with the query. He promised to try his best and said, “Please write down what information you need and send it on WhatsApp.” As he instructed, I sent a message on WhatsApp. I continuously followed up with him. After two weeks, on June 15, he only emailed the details of inactive accounts in banks and financial institutions and said, “Only this much information is available for now.”

The information he provided was incomplete. The subject I was looking for was not found. Now, the only solution was to submit an application under the Right to Information. On June 16, I emailed an application to the Rastra Bank stating, “Please provide the detailed information on how much money is deposited in inactive accounts in which banks in Nepal’s banks and financial institutions.”

Even after that, I did not stop following up with Neupane. An email arrived a month later, on July 20. Finally, I received the full information as requested. And the news was written: Rs 188 billion accumulated in inactive accounts. This is a very large sum of money left behind by account holders in inactive accounts. If I had not continuously followed up, the Rastra Bank would have tried to shirk its duty by only providing the details of inactive accounts.

Another body that hesitates to provide information is the Ministry of Finance. I had registered six applications requesting information at the Ministry of Finance over a period of six months. However, the Ministry of Finance has not provided any information as requested. That is, the Ministry of Finance is not transparent in information dissemination. In 2011, the Ministry of Finance concealed information about dozens of companies found to have evaded tax using fake VAT bills, citing the violation of the taxpayer’s right to privacy. However, at that time, Freedom Forum used the Right to Information to make public the names of the tax-evading companies and the amount of tax evaded. Since then, the Ministry of Finance has shown even less eagerness in disseminating information.

There are numerous tax-related disputes in Nepal. The Ministry of Finance is illiberal in making public certain issues under the Customs, Inland Revenue, and Department of Revenue Investigation. Citizens must make a great effort to obtain information about foreign grants, contracts, various purchase payments, and subsidies given to individuals and various organizations.

The singular argument of Ministry of Finance officials for not providing information is that it is their duty to keep taxpayer details confidential.

It has become even easier for them: point to the information officer and shirk the responsibility. They say, “There are a spokesperson and an information officer; meet them.” In many offices, the information officers and spokespersons themselves are frustrated. They also do not receive the information.

A new practice in government bodies is to shirk responsibility by saying that providing information is solely the job of the information officer. Furthermore, they are seen attempting to deny the right to information by invoking the right to privacy. They consider providing information akin to dividing up their own property.

Ideally, the work done by individuals in public life should not be interpreted by linking it to private life. When a public figure’s actions harm the state, attempts should not be made to conceal it as their private matter. In cases where the rights to privacy and information clash, national interest should be paramount. However, there is no sense that government officials fully accept the fact that the state system should be run transparently.

I submitted an application to the Ministry of Finance requesting information on how much loan and grant the Chinese government has given to Nepal over the past decade and where it was spent, but the Ministry of Finance provided incomplete information and deferred the matter. On June 11, I registered an application requesting details of where the northern neighbor’s grants and loans were spent.

However, after following up for a month, I received a two-page document that only listed the details of 22 agreements made between Nepal and China over a ten-year period.

I requested another piece of information at the Ministry of Finance: “How much money was spent on compensation for the construction of infrastructure projects in Nepal over five years?” Finance officials dismissed this subject without providing any information. Information on compensation for 10 different projects was collected, and the news was written: Large projects caught in the trap of compensation.

Rameshore Khanal, the finance minister of the government formed after the Gen Z movement, had stated that by removing fragmented projects from the budget, Rs 120 billion had been secured for elections and reconstruction. But the citizens’ concern was which projects mentioned in the budget were cut? When I went to the Ministry of Finance with the same question, I was told that the details of many projects could not be provided at once. So, I registered an application under the Right to Information on October 8: “Provide the detailed information, including the budget, of the projects that were cut.”

The details were received on October 14, but they were not as requested. The information provided by the Ministry of Finance was a lump-sum detail of how much budget was cut under the ministries and departments. Details of which projects were halted did not come. To make use of the information received, the news was written: Government cuts expenditure; where was the budget cut?

When the Auditor General’s Office did not provide information, I requested the same information at the Ministry of Finance, where officials said that providing the information was not permissible according to Section 84 of the Income Tax Act, 2002. Section 84 states, “Any authorized officer and other employee must keep confidential all documents and information that come into their possession or knowledge in the course of performing their duties under this Act.”

The state of the Ministry of Labor, Employment, and Social Security in terms of providing information is even more dismal. In 2011, the government of the then-Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai imposed a ban on the registration of foreign employment companies. The Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers sent a copy of the decision to the Ministry of Labor on October 2, 2011, mentioning dispatch number 146.

However, information came that the record of that letter could not be found anywhere in the ministry. This confirms how careless government bodies are regarding the documentation of government documents.

Not only that, but the details of this decision could not even be found at the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers.

The Ministry had also sent a letter to the Department of Foreign Employment, citing the same decision. The department sent it to the Office of the Company Registrar. I registered an application requesting information by citing dispatch numbers 2704 to 2708 of the letter sent by the Department. However, Department Information Officer Tikaram Dhakal said, “The information you are looking for was not found.”

After the document was not found in the body that should keep the record, I had to flip through the files of the Supreme Court to find a copy of the government’s decision. Since the matter had reached the court at that time, the document was found in the court. If the responsible body does not even safely keep a copy of a government decision, the expectation of transparent information provision to the public is very far-fetched.

The right to information is the lifeblood of a democratic state system. The right to information granted by the Constitution is for the citizens. However, journalists, as citizens, have been using it the most. If public bodies become obstacles by concealing information and providing incomplete information even to journalists, who are considered to have access to information sources, one can easily assess what kind of behavior they show to ordinary citizens.