Unnecessary spending on district-level government offices against the spirit of federalism

KATHMANDU: In Koshi Province, the Education and Youth Division of Phungling Municipality in Taplejung district and the Education Development and Coordination Unit (EDCU) Office under the federal government are located barely one kilometer apart. The work of these two offices is not much different. Both are involved in preparing education development plans, teacher appointments, transfers, and similar tasks. Prakash Paudel, Education Officer of Phungling, says, “Although the municipality and the unit carry out slightly different tasks, their nature is the same. If there were enough manpower, the work currently handled by two offices could be managed from a single place.”

In Karnali Province, the office of Birendranagar Municipality and the Education Development and Coordination Unit, Surkhet, are hardly 500 meters apart. Similarly, the Ministry of Social Development of Karnali Province is located about 900 meters from the municipality and 600 meters from the unit’s office. These three offices all perform similar tasks related to educational development and policymaking.

Grade 8 examinations are conducted by the local level. The Secondary Education Examination (SEE) has been conducted by the Education Development and Coordination Unit. For Grade 12, the examination centers are designated by the EDCU, but the examinations themselves are conducted by the National Examination Board under the federal government.

In addition, for teacher pensions, the local level recommends to the EDCU, and then the unit forwards the recommendation to the ministry, resulting in duplication of work. Conflicts often arise between the local level and the coordination unit in matters such as teacher appointments and transfers.

Nepal’s Constitution has given the right to manage basic and secondary education to local levels and the right to provincial universities and higher education to provincial governments. However, the Education Development and Coordination Unit, which has entered as a federal representative in between, has been working in a way that interferes even with the jurisdiction of the local and provincial governments. With the same nature of work being carried out in duplication, the state is incurring unnecessary expenditure.

Redundant structures and unnecessary staffing

Local levels have been operating their own separate education branches, yet the government has established EDCU in all 77 districts to perform the same work. Each of these units has 5 to 9 staff members appointed. In this way, for work that could be handled by local levels, nearly 600 employees are unnecessarily employed across the country. The Ministry of Education has allocated a budget of Rs 824 million for the coordination units for the fiscal year 2025/26. Of this, the recurrent expenditure—covering salaries, allowances, and benefits of the employees—alone amounts to Rs 802.4 million.

The new constitution issued in 2015 assigned the authority for education up to the secondary level to local levels. During the implementation of federalism, the Cabinet meeting on April 10, 2018, decided to abolish the former District Education Offices and establish Education Development and Coordination Units under the District Administration Offices. Subsequently, on April 24, 2018, a ministerial decision assigned 20 responsibilities to these units, some of which duplicate the authority of local levels.

The bill titled “Bill to Amend and Integrate School Education Laws”, registered at the Federal Parliament Secretariat on September 13, 2023, proposed re-establishing the Education Department and District Education Offices. This indicates that the government itself was attempting to reinstate the district-level structures it had previously abolished.

Federalist Khimalal Devkota comments, “If the offices that existed at the district level under a unitary system are deemed necessary in federalism as well, then what was the point of establishing provincial and local levels?”

Another structure without significant work: District Coordination Committee

Similar to the EDCU, another structure with little work is the District Coordination Committee (DCC). While the EDCU is a unit under the federal ministry, DCC is a separate structure provided for in the Constitution. However, the concepts and roles of both run contrary to the spirit of federalism.

According to the vision of federalism, the Constitution established three levels of government: local, provincial, and federal. Accordingly, structures such as districts, zones, and development regions under the unitary system were abolished to directly implement a three-tier government system.

Yet, in contradiction to the spirit of Article 220 of the Constitution, structures of federal and provincial bodies were inserted through the arrangement of District Coordination Committees. The condition of these coordination committees in all 77 districts is like the Nepali proverb: “There’s no work, yet no leisure either.”

Office building of the Kathmandu District Coordination Committee. Bikram Rai/Nepal News

District Coordination Committees: Constitutional role, ineffectiveness, and costly political tools

The Constitution assigns the District Coordination Committees (DCC) responsibilities such as coordinating between federal and provincial offices and rural/municipal governments, maintaining balance in development and construction activities, and monitoring them.

The Constitution also stipulates that a person who is a member of a rural or municipal assembly can be a candidate for DCC chief, deputy chief, or member, and if elected to DCC, that person’s position in the rural or municipal assembly automatically becomes vacant.

As a result, DCC often includes nominated rural or municipal council members and elected ward members. When trying to mediate in disputes, these members are often not trusted by the chiefs and deputies of the local councils. Monitoring by DCC is also ineffective.

Provincial and federal offices largely ignore them. According to a study conducted four years ago by Girdhari Dahal, Associate Professor at Prithvi Narayan Campus, Pokhara, on “The Role of District Coordination Committees in Nepal’s Federalism,” the lack of knowledge of DCC officials has rendered their monitoring work largely meaningless, and their ambiguous capacity leads local levels to show them little respect.

To maintain district structures contrary to the spirit of federalism, leaders such as then- Nepali Congress leader and current President Ram Chandra Poudel, then-CPN-UML leader and current Unified Socialist Party Chair Madhav Kumar Nepal, and others played key roles.

The decision to include DCC in federalism was made based on the preferences and influence of leaders, without any study or research on whether district structures were necessary. Local governance expert and former Chair of the Association of District Coordination Committees of Nepal (ADDCN) Krishna Prasad Sapkota, notes that during state restructuring, even when it was opposed on the grounds that districts were unnecessary after provinces were formed, major party leaders insisted districts were essential. He says, “This is not a necessity-based structure; it is a leader-centric structure. However, those leaders who demanded districts at the time now claim they are no longer needed.”

A structure established according to political preference but incapable of performing real work mainly serves political parties as a means to provide jobs to their cadres. Each District Coordination Committee has nine members: one chief, one deputy chief, and seven members, across all 77 districts.

This arrangement provides service facilities to 693 political cadres. Provincial governments have enacted laws to provide salaries and benefits to DCC officials.

For example, Koshi Province legally provides the chief with a monthly salary of Rs 40,000, a vehicle, and housing; the deputy chief Rs 35,000 with a vehicle and housing; and each member Rs 15,000. This results in a monthly expenditure of Rs 180,000 and an annual expenditure of Rs 2.16 million for a single DCC. For 14 DCC in Koshi, annual salaries alone cost Rs 30.24 million, and including allowances, vehicles, and housing, the total reaches around Rs 40 million.

A structure established according to political preference but incapable of performing real work mainly serves political parties as a means to provide jobs to their cadres.

In Bagmati Province, the DCC chief receives around Rs 44,000 per month, and with allowances, about RS 50,000, plus fuel and vehicle benefits. The deputy chief receives RS 35,000, which with allowances totals around RS 40,000, plus a vehicle or an additional RS 10,000 if no vehicle is provided. Members receive at least RS 20,000 per month. Combined, a single DCC costs about RS 230,000 per month and RS 3 million per year in official benefits. For 13 DCC in the province, annual expenditure for officials alone is about RS 39 million. Other provinces similarly provide salaries, allowances, and facilities at comparable levels.

District Coordination Committees and the cost of staffing

The previous figures covered only the expenses of DCC officials. Beyond the officials, each DCC has provisions to employ up to 13 staff members, ranging from under-secretary and personal secretary to office assistants. According to the sanctioned posts, not all DCC have the same number of employees. If each district is assumed to have 10 staff, then across 77 districts, there are 770 employees.

According to Ashok Kumar Ghimire, General Secretary of the ADDCN, the government provides approximately RS 15 million annually to each DCC. For the current fiscal year, the federal government allocated RS 1.2951 billion to the DCC, while provincial governments also provide separate budgets.

For instance, this year Bagmati Province allocated RS 4 million to each DCC. Ghimire says, “Some provinces have allocated up to 4 million. Some of the federal budget also gets returned. Our budget is adequate, but the role has weakened.”

For DCC, which perform almost no real work, the federal and provincial governments together spend roughly RS 2 billion annually. This has led to occasional calls for the structure to be abolished. On September 14, 2024, then-Minister of Communications and Information Technology, Prithvi Subba Gurung, stated that since District Coordination Committees perform almost no work, they should be abolished during constitutional amendments.

During a program organized by the Policy Study and Research Institute of CPN-UML, Minister Gurung proposed this, prompting the ADDCN to issue a protest statement. Bharat Kumar Bhattarai, Director of ADDCN, argued that the state must pay attention to structures provided for in the Constitution. He said, “Either the district structures should not exist at all, or if they do exist, someone must monitor them!”

During state restructuring in 2015, the government established a commission to determine the number and boundaries of rural municipalities, municipalities, protected, and special autonomous areas.

The commission recommended establishing between three hundred and five local units across the country. However, this recommendation was ignored by the leaders. Instead of following expert studies and suggestions, leaders unilaterally decided on 753 local units and retained the old districts.

The commission’s then-chair, Balananda Poudel, says, “If only around 300 local units had been created, collaboration between local units could have been more effective. It would have been better not to retain the district structure. That would have strengthened federalism.”

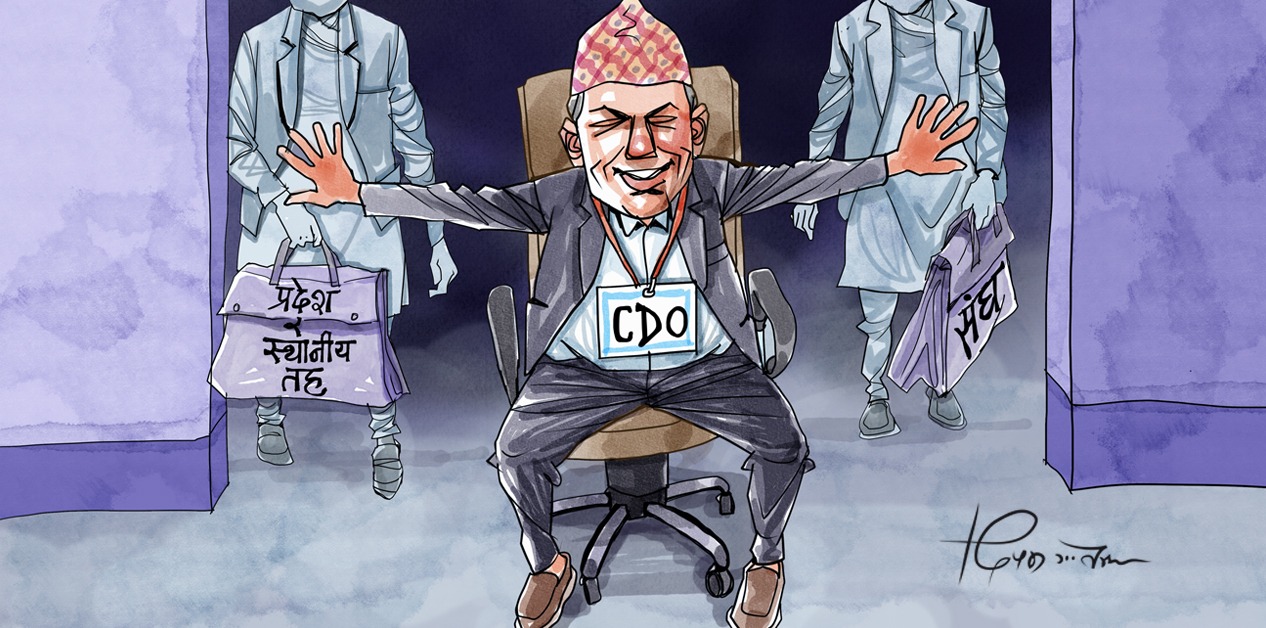

The rule of CDOs

Another federal structure that weakens federalism and resembles unitary governance is the District Administration Office under the Ministry of Home Affairs. This semi-judicial structure dealing with law and order exists in all 77 districts, with some districts having additional Area Administration Offices. The federal government has maintained this structure for tasks that could be performed by provincial Ministries of Internal Affairs and Law.

Provincial and local governments have expressed dissatisfaction with the work of the District Administration Offices. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when the federal government assigned leadership responsibilities to the district administration, provincial and local levels expressed discontent.

Meetings of the District Disaster Management Committees, led by Chief District Officers, often proceed without participation from local chiefs, causing issues. For work that could be handled by provinces and local governments, unnecessary expenses are being incurred from the state treasury.

For the current fiscal year alone, the federal government has allocated RS 2.58 billion for the District Administration Offices. Former Minister of Internal Affairs and Law of Koshi Province, Indra Bahadur Angbo, notes that maintaining the District Administration Offices leads to unnecessary expenditures and duplication of work.

District structures in federalism: Redundant and costly

Services that currently flow through the District Administration Offices and other district-level structures could be easily delivered directly from the municipal level. However, the District Administration Offices have been retained in federalism mainly to maintain the authority and influence of Chief District Officers (CDOs).

Political leadership and the self-interest of employees have largely driven this arrangement.

Similarly, the District Police Offices do not align with the spirit of federalism.

Provincial and local governments have expressed dissatisfaction with the work of the District Administration Offices.

The Nepal Police has 2,600 offices ranging from federal and provincial levels to local ward offices. In the current fiscal year, the government has allocated RS 29.46 billion for District Police Offices alone, with RS 28.37 billion earmarked for recurrent expenditures.

This budget covers district police offices as well as subordinate Area Police Offices, police posts, and temporary police outposts. Lower-level police offices still operate under the directives and control of the district structure.

Former Minister Indra Bahadur Angbo notes, “Passport services can be provided online, citizenship through local levels, and the remaining law and order responsibilities can be handled by the provincial government. Structures like District Administration and District Police Offices are not necessary.”

The Department of Prison Management under the Ministry of Home Affairs reports that there are 75 prison offices across 72 districts in the country. The structure of these prison offices remains largely the same as in the previous unitary system. Under the title of “Prison Office,” the Ministry of Finance allocated RS 2.88 billion for the current fiscal year.

Over 20 offices in each district

To maintain district structures contrary to the principles of federalism, more than 20 government offices exist in each district. These district structures under federal and provincial ministries continue to be established without restriction.

In the budget statement for fiscal year 2023/24, the government had announced the abolition of district-level offices such as election offices, statistics offices, and postal offices in all 77 districts. However, in this fiscal year, the then-KP Sharma Oli government allocated RS 735.6 million for election offices alone, which results in an annual expenditure of RS 500 million for district election offices.

In the same year, the government allocated RS 332.8 million for district statistics offices, RS 3.06 billion for district postal offices, RS 818.4 million for district government attorney offices, and RS 4.40 billion for district courts.

Under federal ministries, district offices of prisons, surveying, land revenue, financial comptroller, the National Investigation Department, and the Armed Police Force are also active. Some offices are simply the old district offices operating under a different name.

For example, the former District Forest Office now functions as the Division Forest Office under the provincial government. For the Division Forest Office, the federal government has allocated RS 59.2 million for the current fiscal year, of which RS 54.2 million is earmarked for recurrent expenditures.

This means that most of the federal budget is spent on employee salaries and benefits. In addition, provincial governments also allocate budgets for Division Forest Offices: Koshi Province allocated RS 851.971 million, while Bagmati Province allocated RS 879.067 million.

Similarly, former District Agriculture Development Offices now operate under provincial governments as Agriculture Knowledge Centers. For the current fiscal year, Koshi Province allocated RS 199.499 million for its Agriculture Knowledge Centers. Each province has district-level Agriculture Knowledge Centers, with annual expenditures reaching billions of RS.

The Public Expenditure Review Commission, 2018, noted in its report that during the implementation of federalism, the federal, provincial, and local governments competed to increase their presence among the public, which created duplication of work and failed to curb the growth of recurrent expenditures. The report states: “Federal ministries divided the pre-federal scope of work among the federal, provincial, and local levels according to their convenience, resulting in duplication of tasks in some cases.”

Local governance expert Sapkota argues that since local levels can handle sectors like agriculture and livestock, there is no need for district-level structures under the federal or provincial governments. He says, “The Constitution grants authority to local levels. Provinces should handle production-related work and marketing. District-level structures are unnecessary and should be abolished.”

Redundant district offices undermining federalism

In some districts, offices such as the Department of Cottage and Small Industries, Food and Quality Control Office, and Animal Service Office exist at the district level. This indicates a competitive expansion of district structures between the federal and provincial governments.

Federalism is meant to decentralize power, but contrary to this principle, activating old district structures and establishing district-level offices under federal and provincial governments has led to two major issues: first, it undermines the spirit of federalism by allowing federal and provincial dominance at the district level; second, creating duplicate structures for the same functions increases administrative costs and results in unnecessary expenditure from the state treasury.

The Public Expenditure Review Commission, 2018, noted in its report that during the implementation of federalism, the federal, provincial, and local governments competed to increase their presence among the public, which created duplication of work and failed to curb the growth of recurrent expenditures.

In the Himalayan district of Taplejung, of the 50 government offices, more than half represent district-level structures of the federal and provincial governments, covering police, administration, health, forestry, agriculture, election, and postal services.

Even in the smallest district by area, Bhaktapur, there are 50 government offices according to the District Administration Office, with about half being district-level offices.

In the smallest district by population, Manang, of the 34 government offices, 22 are district-level offices. Based on this, if we assume a district has 20 district-level offices, there are at least 1,540 district-level government offices across 77 districts.

Federalism experts argue that structures other than the federal, provincial, and local governments are unnecessary. Federalism is intended to deliver services directly to people’s doorsteps, so a unified model is required, says federalism expert Khimalal Devkota.

He states, “Federal structures mean direct flow from local to provincial and from provincial to federal. District structures in between are unnecessary. During constitutional amendments, district structures should be abolished.”

During state restructuring, provinces were originally created based on districts. Similarly, parliamentary electoral constituencies are still based on old district boundaries. While federalism requires clear allocation of authority, retaining district structures perpetuates the old centralized mindset.

The Public Expenditure Review Commission’s report notes that some federal bodies continue to retain expenditure authority according to previous centralized practices and keep lower structures and staff under their own control.

Seven years ago, the commission recommended removing unnecessary district structures and transferring their functions, but this suggestion has not been implemented. District structures that exist as intermediaries between the three tiers of government not only discredit federalism but also risk making it ineffective.

Since the Constitution allows for a review after 10 years, experts suggest that district structures should be abolished through constitutional amendments at that time.

Former commission chair Balananda Poudel also notes that district structures are unnecessary for the current type of work. He states, “Many federal ministries currently maintain district structures to deliver services.

Instead of keeping the old district-by-district system, service centers can be established according to the number of local units and actual requirements. This reform is necessary to make federalism more efficient, and it should be included in the constitutional ammendments.”