Translating literary works written in the Nepali language into English alone is not enough; in keeping with Nepal’s diversity, it is equally essential to translate works from other mother tongues as well.

Aastha Giri had twice attempted to read Palpasa Café by Narayan Wagle but failed. As a Development Studies student, she finds it easier to read in English than in Nepali. Because of language difficulties, she had not been able to finish the novel. Recently, she completed the English translation of Palpasa Café. The 25 year old resident of Godavari says, “Since the original was in Nepali, I tried two or three times to read it in Nepali, but unfamiliar words and sentences kept confusing me. I had heard for a long time that it was a must read book, so even though it was in translation, I finally finished it in English.”

After Palpasa Café, she is now reading the English version of Karnali Blues by Buddhisagar. She has also placed Shirishko Phool, Radha, and Seto Dharti on her reading list. Her plan is to read the English translations of all widely discussed Nepali books.

Aastha is not alone in actively seeking English translations of Nepali books. She says, “Many of my friends are also reading Nepali literature in English.”

English translations, once considered primarily for foreign readers, are now increasingly targeting Gen Z readers like Aastha Giri.

According to Michael Hutt, the translator of Karnali Blues, the English translation of the book has already sold around 3,500 copies. He says, “Many Nepali readers tell me they read it in English for the first time. Reviews on Goodreads also show that many of its readers are Nepali.”

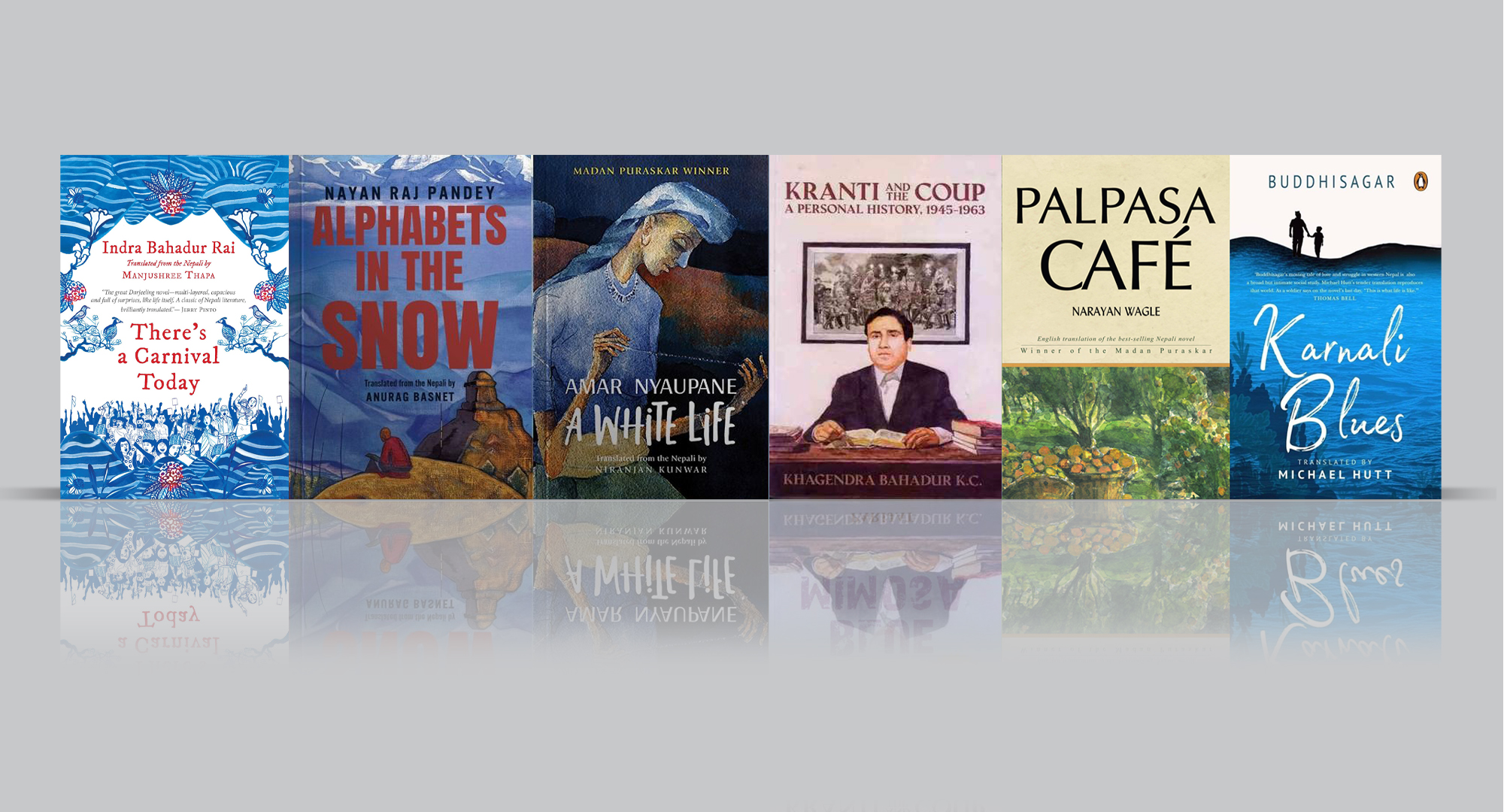

English translations of Nepali creations were once meant for foreign readers but lately they have been increasingly targeted at Nepal’s Gen Z as well. Only recently, some prominent Nepali books have been published in English translation.

In the third week of last December, English translations of two well known authors were released on the same day: A White Life and Alphabets in the Snow. These are translations of the Madan Puraskar winning novel Seto Dharti by Amar Neupane and the widely read Sallipir by Nayan Raj Pandey. Seto Dharti was translated by Niranjan Kunwar and Sallipir by Anurag Basnet. The publisher FinePrint has also published the translation of Phatsung.

The translated versions of the novels by Neupane and Pandey were also launched in Delhi, India. Last Friday, the English translation of former Foreign Minister Bhekh Bahadur Thapa’s memoir Rashtra–Pararashtra: From Monarchy to Republic was released under the title A Life in Public Service. Translated by Prawin Adhikari, the English edition was published by Penguin India.

Historically, English in Nepal was not the language of any particular community but of a specific elite class. After 1951, when it was incorporated into the formal educational curriculum, it began to expand. English entered the higher secondary curriculum of Tribhuvan University in as early as 1959.

Even during the Rana period, a small group with access to education was already capable of writing or translating books in English. Poet and essayist Laxmi Prasad Devkota was one such figure. He wrote in English and translated some of his own works. Coronation Day in Kathmandu and Other Essays is a collection of his English essays, including one written in the context of King Mahendra’s coronation in 1956. Devkota also translated several of his own works.

The translation of Nepali literary works into English gained momentum from around that time. The journal Studies in Nepali History and Society (Year 4, Vol 2, 1999), published by Mandala Book Point, included a bibliography of translations of Nepali and Nepal Bhasa literature.

This bibliography shows that around the 1960s, a significant number of Nepali and Nepalbhasa literary works were translated into English. The translators of that period included Madhavlal Karmacharya, Tirtharaj Tuladhar, Tejratna Kansakar, and Madhusudan Devkota, among others. Writer Bharat Jungam, on his blog, has provided information—based on sources from Ishwarman Ranjit—about novels that were translated into English.

According to that bibliography, the formal beginning of English translations of Nepali novels dates to 1972. The first translated novel was Shirishko Phool by Parijat, jointly translated by Tanka Bilas Varya and Sondra Zeidenstein under the title Blue Mimosa. Zeidenstein herself published the book in 1972.

In 1984, the historical novel Seto Bagh by Diamond Shumsher Rana was translated by Greta Rana as The Wake of the White Tiger. That same year, Larry Hartsell translated Khaireni Ghat by Shankar Koirala. It was published by Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

According to a list compiled by writer Bharat Jangam, between 1972 and 2000, twelve novels by eleven novelists were translated from Nepali into English. By 2005, the number had reached twenty one. Notable works include Basain, Rupmati, Alikhit, Palloghar Ko Jhyal, Sumnima, and Karagar. Some were published in Nepal and India by private or small publishers. Translators and publishers included Nepalis within Nepal, members of the diaspora, and foreigners.

Translations of stories, poems, and essays continued during this period. However, translators such as Michael Hutt and Manjushree Thapa believe that translation work increased significantly after the political changes of 1990.

La.Lit Magazine, edited by Rabi Thapa, has become a major platform for publishing translations of contemporary and senior writers in both fiction and non-fiction. It prioritizes social diversity and representation and has introduced many new generation translators.

Michael Hutt believes that both the quantity and quality of translations have improved in recent years. In his view, early translations were introductory works aimed at presenting Nepali literature to the outside world. “The quality of translation was not very good, and the English sounded unusual. The translations I read were not satisfying,” he says.

Even if earlier translations were imperfect, they connected one generation of translators to the next. Each generation has helped build the field further.

One defining feature of English translation is that it crosses national and geographic boundaries. After reading Nepali Visions, Nepali Dreams: The Poetry of Laxmi Prasad Devkota by David Rubin, British scholar Michael Hutt became interested in Devkota’s Muna Madan and other works. Hutt’s own translations, including Himalayan Voices and Modern Literary Nepali: An Introductory Reader, became key resources for Manjushree Thapa in understanding Nepali literature.

In a 2018 lecture series at Martin Chautari, Thapa shared how her literary thinking developed and expressed deep gratitude to Michael Hutt for guiding her toward Nepali literature. Since then, she has made significant contributions to English translations of Nepali literature.

Contemporary translators have helped bring the works of many modern writers to foreign readers and publishers. Nayan Raj Pandey says, “For a writer like me, when a book is published in English, there is hope that it might catch the attention of foreign readers and publishers. If major foreign publishers take interest, it could open doors to better opportunities in the future.”

He also notes that English readership within Nepal is growing. “From students in grades eight and nine to mature readers, Sallipir has touched many. I believe its story can also resonate with readers outside Nepal.”

For Amar Neupane, this is his first experience of having a novel translated into English. Discussions about translating the book had begun ten years earlier. Because it addresses child marriage, there was an expectation that it might interest foreign readers.

He says he is delighted that the English translation of his book has been published for the first time, adding that the number of readers who read in English is also increasing within Nepal.

When visiting the United States and the United Kingdom, he was often asked, “Is your book not available in English?”

Many writers hear this question abroad. At such times, he would wonder when the translation would finally appear. Though translated books do not receive the same immediate reactions or sales as Nepali editions, both Neupane and Pandey feel that their authorial brand value has increased after the English translations.

“Now the translations of Sallipir and Seto Dharti can easily be found on online platforms like Amazon,” says Pandey. “As more translations appear, digital platforms will connect us with readers around the world.”

The English translation of Phatsung, translated by Ajit Baral, was shortlisted for India’s JCB Prize for Literature, one of the country’s major awards for works translated into English.

Manjushree Thapa has written that Indra Bahadur Rai remained overlooked in India largely because his works were not translated into English. Although his critical works were awarded by the state, he was not widely read. “Until my 2017 translation of his novel and Prawin Adhikari’s translation of his stories in the same year, only a few of his stories were available in English,” she notes. “Indian readers who recognize Mahasweta Devi did not know Indra Bahadur Rai. Bringing his work to Indian readers was my greatest satisfaction as a translator.”

Michael Hutt states that translation expands the international reach of Nepali literature.

However, translator Prawin Adhikari believes that while translation activity has increased, the market response has not been particularly encouraging. “Although the number and quality of translations seem to have grown, sales have not been very strong,” he says. “Translators still do not have a financially secure environment to work in.” He adds that publishers invest heavily in advertising but have not built a reliable foundation for translation work.

Niranjan Kunwar shares a similar view. He says it took him two years to translate Seto Dharti, working an average of three to four hours daily. “It is financially challenging to pursue translation as a profession,” he says.

Adhikari notes that translating fifty thousand words takes him at least a year. Sometimes a single story can take months. Currently translating stories by Khagendra Sangraula, he says one story titled Seteko Sansar, about nine thousand words long, has taken him a year to complete.

Translation, he says, is mentally exhausting. Even so, he hopes that once the current story is finished, work on the rest of the collection will move faster.

This shows that translation requires not only linguistic skill and literary and cultural knowledge but also patience and discipline. The financial return does not match the time invested. As a result, translators are often driven more by passion than by money.

For Kunwar, who comes from an American background, translation is an important process for learning the Nepali language and exploring his interests. Currently preparing to bring out translations of various writers and literary works, he says, “Translation takes you on a mental journey across different times and contexts. It broadens the scope of knowledge and also teaches discipline.”

For Michael Hutt, the desire to allow other foreign readers to access Nepali literature fuels his work.

Manjushree Thapa argues that debates about Nepali literature and the literature of Nepal must continue.

Works translated into English are often treated as representative of Nepal, but Nepali literature includes far more than texts written in the Nepali language alone. Other linguistic traditions remain underrepresented.

Michael Hutt observes that many voices were suppressed during the Panchayat era, and only after 1990 did greater representation of Indigenous communities and women emerge in literature.

In the preface to her 2021 translation Secret Places, Manjushree Thapa wrote that Nepali literature is not yet inclusive.

She argues that works outside the established literary canon must be included. Representation of non Khas linguistic communities, women, Dalits, Indigenous groups, and other marginalized communities remains incomplete.

An issue of La.Lit Magazine (Issue 8) edited by Thapa focused specifically on marginalized literature, featuring poems, stories, and essays by writers from diverse linguistic backgrounds.

In the editorial of La.Lit, Thapa writes that in a multilingual nation like Nepal, the literary canon should have included a substantial portion of works from languages other than Nepali, but it does not. “There should have been organized efforts to translate literature from various languages into Nepali, but there have not been.”

This shows that Nepali literature is broader than what is published in the Nepali language alone. Translation must prioritize works from Nepal’s many mother tongues to reflect the country’s social diversity.

“Translation should and, it does, help bring forward the voices of people from different genders, castes, classes, regions, and minority communities,” says Niranjan Kunwar.

“However, if we truly want to address Nepal’s diversity, translating Nepali literature into English alone is not enough. Extensive translation work must also take place among Nepal’s own languages,” says Prawin Adhikari.

This means that literature written in languages other than Nepali has yet to be fully recognized as part of Nepali literature. However, that process has begun. If translation efforts continue, they will increasingly reflect the diversity of society and the plurality of the nation, allowing the international community to see and understand Nepal’s many faces.