Pirated books sold openly in Kathmandu

KATHMANDU: Indian author Rithvik Singh’s book “I Don’t Love You Anymore” has become one of the best-selling books in the Nepali market. Interestingly, even before its official release in India, illegal or pirated copies of the book had already flooded bookshops and online stores in Kathmandu.

Published in 2024 by Ebury Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House, the official edition of the book sold over 15,000 copies in Nepal. However, booksellers say the number of pirated copies sold was even higher.

Another similar example is “We Were Never Meant to Be” by Palle Vasu, published by Manjul Publishing House in India. Pirated copies of this book were already available in Kathmandu’s book markets a month before its official release.

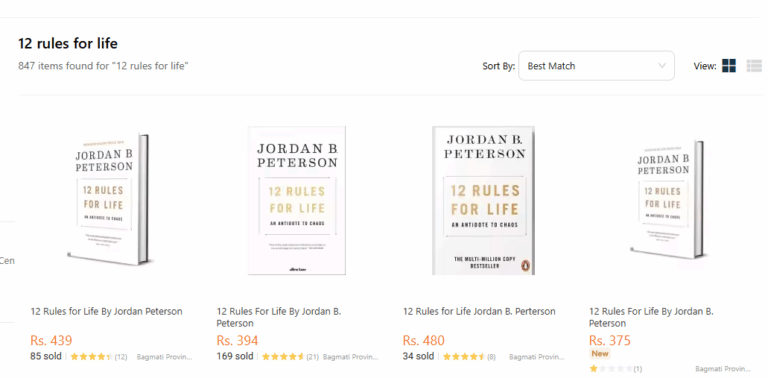

These two examples show the extent of the trade in pirated or unauthorized foreign-language books entering Nepal. Most bookshops in Kathmandu and online platforms such as Daraz and Grey House are currently flooded with unlicensed editions. Because of these fake copies, the same book often appears in two or more different covers, and prices vary widely.

The American author James Clear’s 2018 book “Atomic Habits” is also among the best-selling titles. The official price of the book is Rs 1,280, but on online sites like Daraz and Grey House, numerous versions are sold for as little as Rs 100 to Rs 200.

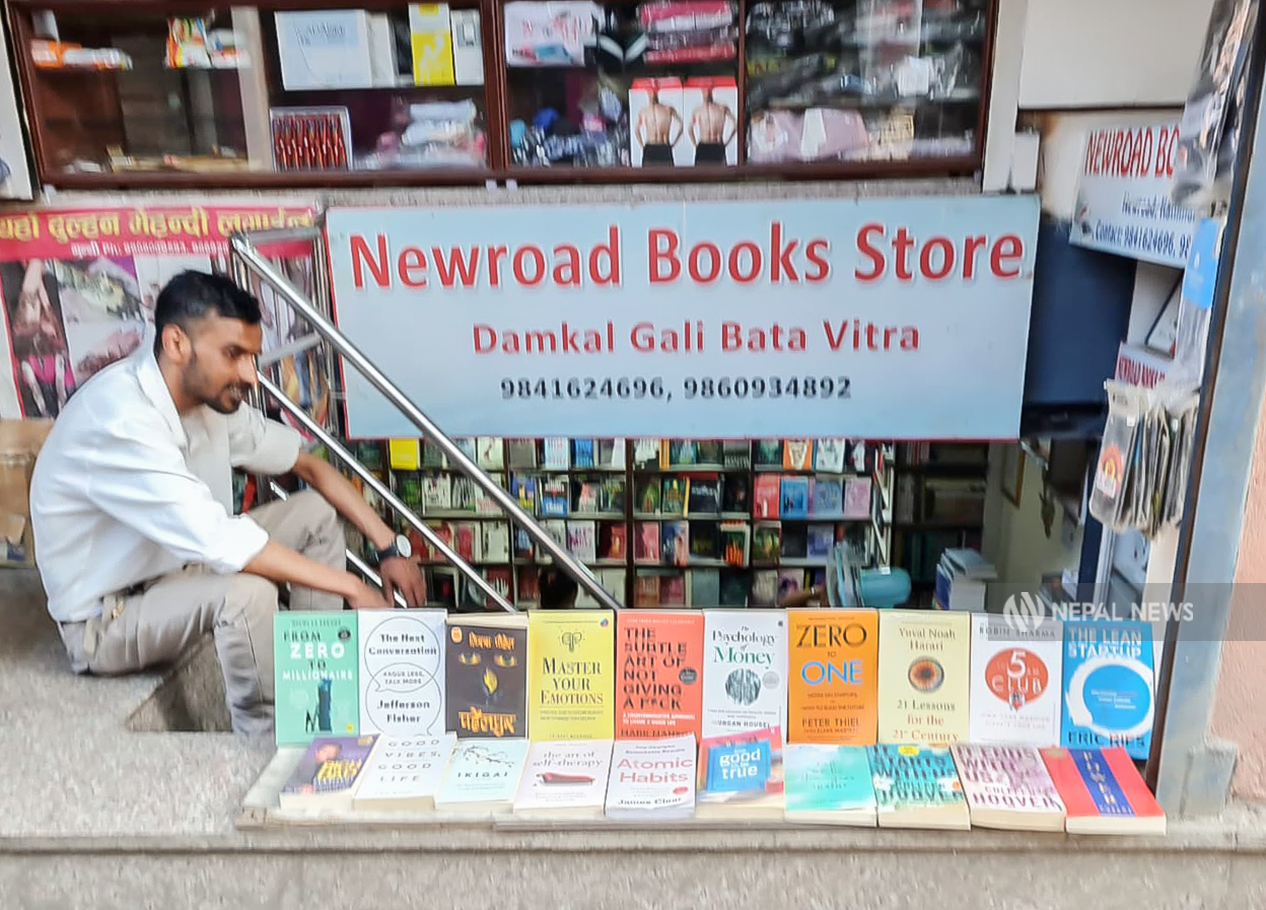

At the New Road Books Store, located in an alley near Juddha Salik, I asked the price of Atomic Habits. Showing two different copies, the shopkeeper asked, “Do you want the cheap one or the expensive one? The expensive one costs up to Rs 1,100, the cheap one Rs 200.”

Such a huge price difference for the same book! I asked the woman again,

“How can it cost only Rs 200?”

She replied, “Because we bring them in bulk.”

“Where from?” I asked.

“From India,” she said.

Newroad Books Store in New Road. Photo: Prabhakar Gautam/Nepal News

Both types of books — the genuine and the fake — come to the Nepali market from India. At first glance, the books look identical, but on closer inspection, their quality differs greatly. The expensive versions are officially published with quality paper and printing, while the cheaper ones are unauthorized pirated copies printed without the consent of the author or publisher.

At first glance, such pirated books look identical to genuine ones—from the cover design to the binding—but a closer look reveals many flaws. These books are often printed from PDF files, making the text smaller and less sharp than in the original editions. Printed on poor-quality paper, they frequently contain printing errors, blurry text, and even missing pages. Yet, because these fake copies are sold many times cheaper than the originals and are easily available through home delivery, many readers are drawn toward cheap, counterfeit books.

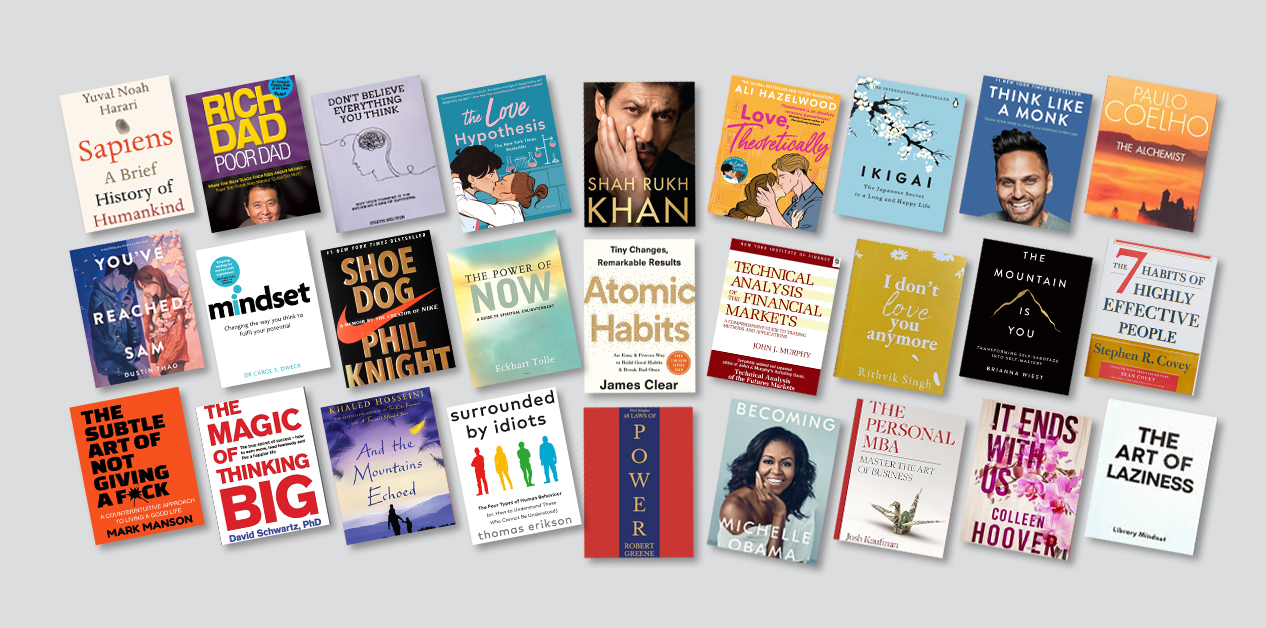

Recently, self-help books have become highly popular among Nepali readers. Titles such as Rich Dad Poor Dad, The Psychology of Money, Think and Grow Rich, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, and Ikigai are in high demand.

Booksellers say there are over 600 foreign-language titles available in the Nepali market, and most of them are pirated. These fake books are widely sold in shops around New Road, Bhotahity, Bagbazar, and Baneshwor, as well as in online stores, where counterfeit editions dominate. Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok are being extensively used to advertise pirated books.

Miller Shrestha, proprietor of MK Publishers and Distributors, says unauthorized foreign-language books now occupy about 80 percent of the market. “Where we used to do business worth one lakh rupees, now it’s only twenty thousand,” he says. “It’s not just me—every bookseller and businessperson who follows the rules is facing the same situation. This happened because there’s a complete lack of regulation and anyone can freely sell fake books in the market.”

Because of the widespread availability of cheap pirated books, legitimate book distributors are not only suffering financial losses but are also facing moral questions from customers. Readers often confront them, saying: “Why is your copy expensive when the same book costs so much less online or in other stores?”

Madhav Maharjan, founder of Mandala Book Point, remarks, “We’re living through a strange irony—those who follow the rules are seen as wrong, and those who break them seem right.”

Birendra Das of New International Books has had similar experiences. He says, “We follow the rules and sell genuine, high-quality books, yet customers accuse us as if we’re doing something wrong. Sometimes we even end up in arguments with them.”

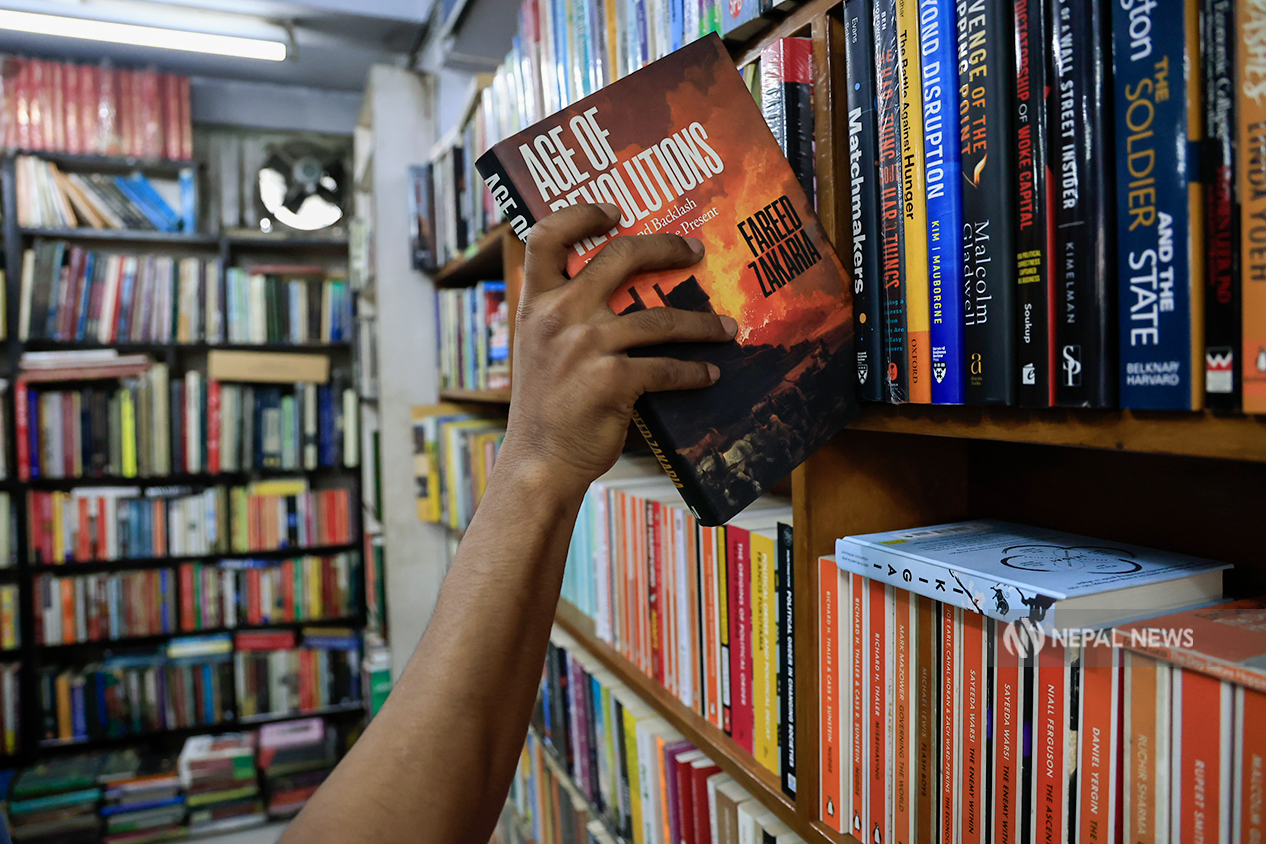

Mandala Book Store. Photo: Bikram Rai/ Nepal News

MK Publishers’ Miller Shrestha describes this situation—where those doing the wrong thing get a free pass while those following the rules face scrutiny—as a form of harassment.

“When we post about genuine books with their official prices on social media, people comment or message saying we’re overcharging,” he explains. “Isn’t that harassment?”

This situation has demoralized genuine booksellers and distributors who have been operating legally for decades. Meanwhile, those selling pirated books are doing brisk business.

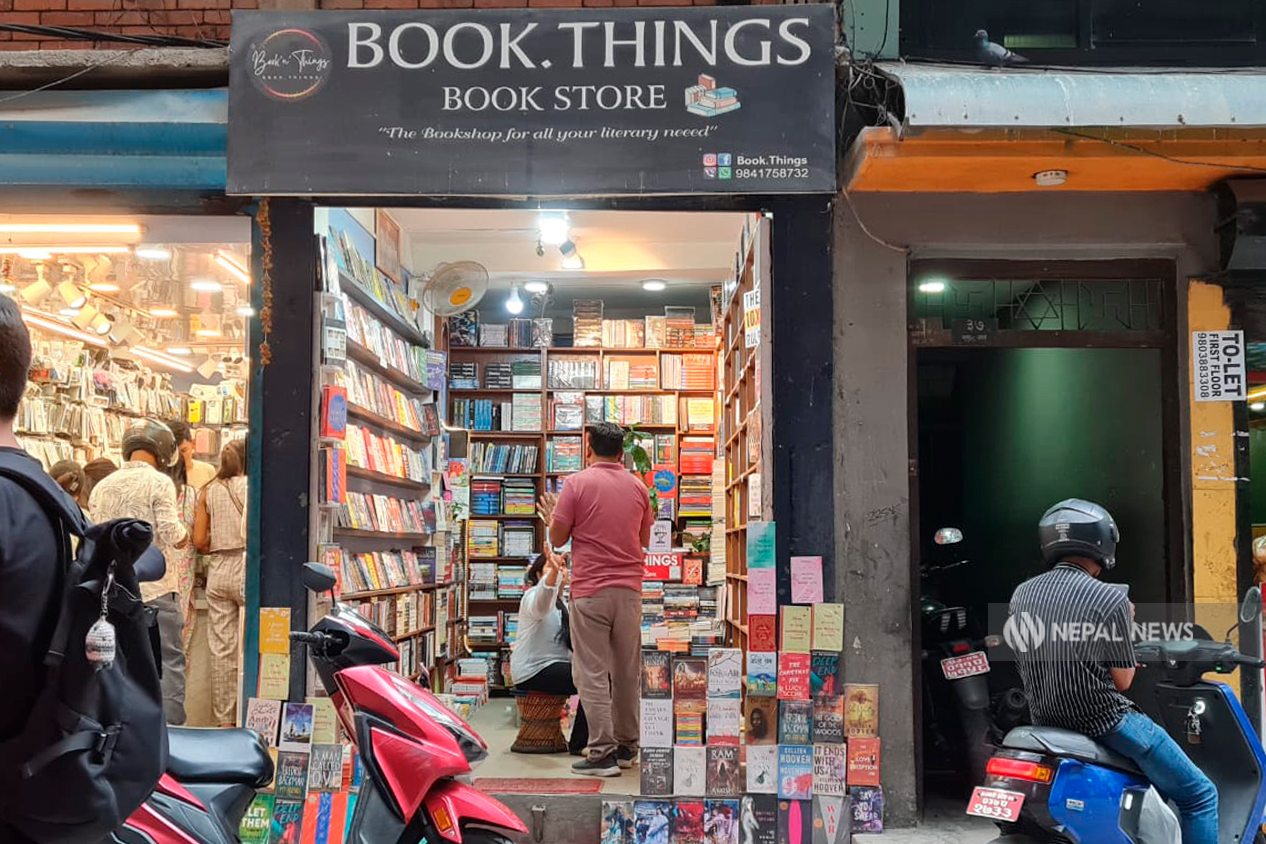

At a bookstore called Book ‘n’ Things, located on the street from Om Bahal leading into Freak Street, this reality is visible. When visited, the shopkeeper said, “Customers get whatever quality they want here. Since books are available at low prices, some customers buy as many as 15 copies at once.”

Even though the books are pirated, many shopkeepers market the poor-quality copies as “original.” Not only do ordinary buyers fall for it, but even seasoned book traders are misled.

Chandra Prasad Shiwakoti, proprietor of Pairavi Book House, who has been in the book business for 35 years, says, “I often go around the bookshops near Bhugol Park in New Road just to observe. Even to me, they confidently try to sell fake books claiming they’re ‘original.’”

In some shops, both fake and genuine books are displayed side by side. Depending on the type of customer, the bookseller offers different qualities and prices.

According to the Nepal National Booksellers and Publishers Association, there are over 10,000 bookshops across Nepal, and the unauthorized market for pirated books has had a serious negative impact on their business.

According to Miller Shrestha, there are roughly 20 major distributors in Nepal who legally import large quantities of books from India. These imports amount to Rs 250–300 million annually. Shrestha estimates, “If there were no pirated books in the market, official imports would have been more than three times higher, likely exceeding Rs 1 billion.”

Rajivdhar Joshi, founder of Kathalaya Inc, estimates that over Rs 50 crore worth of books are imported annually into Nepal. Given that pirated copies sell in larger volumes than originals, this implies that millions of rupees’ worth of pirated books are entering the market.

Official booksellers typically offer 10–20% discounts on a book. In contrast, shops like New Road Books and Book ‘n’Things sell books at 50–80% discounts. Online platforms are even more effective for pirated book sales. Some representative online platforms selling fake books include: Daraz, Book Media, Book ‘n’Things, Book Sanjal, BookCrest, Books Reload, Doraj Book Store, Grey House, Hamro Offer, Kitab Sansar, Lakhe Book Store, Paschimanchal Book Store, Pustakalaya Store, Sanskar Books, Sasto Maa Books, Sasto Maa Kitab, Sandesh Enterprises, Bajrang Bali Book. Some of these also operate physical stores.

Booksellers and businesspeople say that the sale of pirated books has surged since placing books on digital platforms. The rise of online shopping after the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to this trend.

MK Publishers, which sells books wholesale and retail, is based in Bhotahity. According to Shrestha, before COVID-19, the market for pirated books was small. Nearby shops used to hide fake books while selling them. But now things have changed. He says, “Before COVID, shops used to place genuine books in front and pirated copies at the back, selling them discreetly. Now, pirated books are displayed openly in stores from the start.”

Shrestha explains that pirated book sales began with textbooks. Earlier, literary books didn’t sell much, and even with textbook piracy, there were only five to seven titles involved. Even though pirated copies existed, genuine copies sold in hundreds of thousands, so the impact was limited.

Now, piracy has spread to all types of books, including literary works, and pirated copies sell four to five times more than official editions. This has made it extremely difficult for wholesale and retail sellers of genuine books to survive. Madhav Maharjan adds, “Where previously 25 copies of a book would sell, now we can barely sell five. The surge in the pirated book market has put us in serious trouble.”

Book.Things, selling pirated books, located on the road from Om Bahal to Freak Street. Photo: Prabhakar Gautam/Nepal News

Birendra Das of New International Books shares a similar experience. He says, “A book that used to sell 500 copies now sells only 20, and that’s considered a success.”

As the pirated book market undermines official sales, Shrestha is considering moving his shop from Bhotahity because he can no longer afford the high rent. He says, “All booksellers initially open small shops and later expand. Now, only those selling pirated copies thrive, and genuine bookshops are forced to close.”

Alongside literary and self-help books, piracy now extends to curriculum textbooks and foreign language learning books, which are photocopied and sold. Around Pulchok Engineering Campus and Tribhuvan University in Kirtipur, such photocopied books are being sold and distributed. In Bagbazar, ANM Prints House photocopies Cambridge University Press IELTS books and sells them. ANM Prints even posts videos on its Facebook page, advertising a Rs 1,040 book for just Rs 120. According to Das of New International Books, the video has already reached Cambridge Publishing personnel.

In Nepal, books from publishers such as Penguin, Harper, Scholastic, Bloomsbury, Cambridge, Hachette, Pan Macmillan India, and Jaico Publishing House are available. Their South Asian editions are printed by the Indian branches and sent to Nepal. Even though there are official distributors, there is no single exclusive distributor, so anyone can import books through informal channels.

Nepali publishers and booksellers have repeatedly emailed Indian publishers to alert them about pirated books in Nepal. Rajivdhar Joshi says, “Recently, Miller Shrestha and I went to Delhi and informed representatives of three or four major publishing houses about piracy in Nepal.”

Madhav Maharjan has also taken steps to inform publishers, sending them a list of 208 books being sold cheaply in Nepal.

Nepali booksellers sell foreign books imported from India, but they are not the official representatives. As a result, they cannot initiate legal action regarding piracy and must rely on Indian publishers and distributors.

Indian publishers and distributors are aware of the piracy, but they do not act. Joshi explains, “Copyright cases require time and money, which is why they are reluctant. They face piracy problems in India and consider Nepal’s issue not their responsibility.”

Since Nepali booksellers are not official representatives, Indian publisher representatives must file cases in Nepal. Joshi believes that even current Nepali copyright law would work if this step is taken. He says, “If an Indian representative comes here and files just one case, enforcement opens up. While controlling piracy in India is difficult, Nepal’s market is small, and action here could succeed. Maybe we haven’t properly explained the Nepali process?”

Different prices for the same book on online shopping site Daraz

Chandra Prasad Shiwakoti of Pairavi Book House says that at the World Book Fair in Delhi, large numbers of pirated books were openly displayed for sale right at the exhibition gate, in front of authors and publishers themselves. This shows how uncontrolled piracy in India has spread to Nepal and other South Asian countries.

Despite the uncontrolled market for pirated books in Nepal, Shiwakoti remains optimistic, saying, “If relevant associations and the state take even a little initiative and monitoring, book piracy can be controlled.”

The Nepal National Booksellers and Publishers Association (NBPAN), active since 1990, works to protect the rights of booksellers. Many who inform Indian publishers about piracy are current or former members of NBPAN.

In January 2025, NBPAN wrote to Daraz, requesting them to stop vendors selling pirated books. The letter noted complaints from national and international publishers and said, “This has caused major losses to genuine publishers and threatens the survival of the book trade. We request Daraz to permanently ban such vendors and assist in legal action against them.”

Nine months after the letter, pirated books have still not been removed, and their sales continue to increase, raising questions about NBPAN’s effectiveness, says Joshi.

Shiwakoti also questions NBPAN’s slow action: “This organization exists to protect business interests, but how honest are they themselves? Could there be self-interest among members? Have some of them been selling pirated books themselves?”

Shrestha of MK Publishers says that the problem has grown too large for a few vendors to handle; institutional action is necessary. He adds, “An organization like NBPAN must step forward openly and with commitment. Only then can the state and foreign stakeholders be compelled to act.”