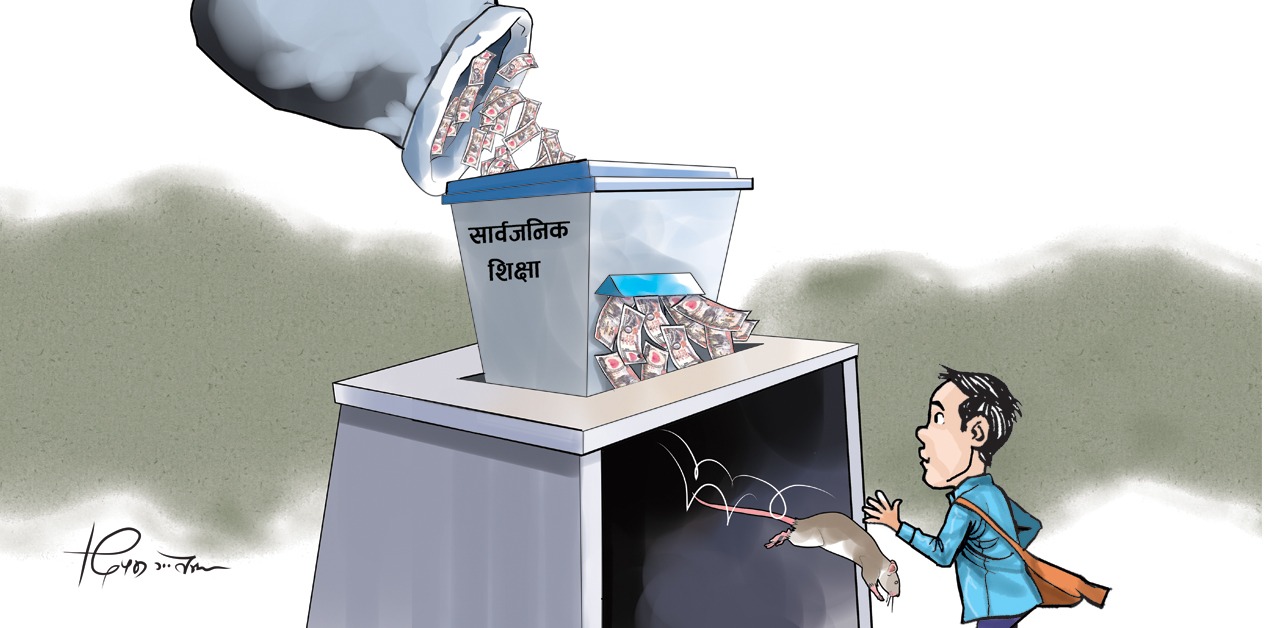

More than Rs 500 billion in grants and loans has been spent on public education reform, but learning outcomes remain poor

It has been 45 years since school education in Nepal has been continuously run on the support of foreign aid projects. During this period, 10 foreign-assisted projects have been implemented in the name of improving school education. Even now, the “School Education Sector Plan (SESP)” is under implementation. Covering the period from 2022 to 2032, SESP is the eleventh education project of its kind.

The main donors to this project include the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), European Union, Finland, Global Partnership for Education (GPE), Norway, and UNICEF, among others. The core objective of the project which is ensuring access to education for disadvantaged and marginalized children is not fundamentally different from the “Education for Rural Development Project”, which was launched in 1980 and ran for five years.

From 2023 to the present, projects with similar nature and objective, such as the School Safety Plan, School Sector Reform Program, School Sector Development Plan, and School Education Sector Plan have been implemented under different names. Earlier, from 2037 BS to 2060 BS, more than two decades saw the implementation of five projects aimed at developing primary, basic, and secondary education. Although their names varied slightly, their nature and objectives largely remained the same.

American projects at the foundation of education

Even when Nepal first formed the National Education Planning Commission (NEPC) with the objective of laying a nationwide educational foundation, donor support was sought. On 23 January 1951, the governments of Nepal and the United States signed an assistance agreement with the stated aim of promoting democracy through the development of the education sector. As a result, an education committee formed in 1953 recommended timely reforms in national education, leading to the establishment of the NEPC in 1955.

According to a research article published on ResearchGate by education researcher Kapil Dev Regmi, this was the first instance of Nepal receiving donor assistance for public education.

While seeking donor support during the early phase of modern education development after the restoration of democracy may have been practical, dependence on donors in the form of loans and grants has continued to this day. “At a time when the country’s literacy rate was only around two percent, the commission deserves credit for shaping the development, expansion, and reform of education,” says educationist Binay Kumar Kusiyait.

“But subsequent foreign projects were centered on donor interests, and bureaucrats and political leadership became entangled in them.”

Indeed, implementing foreign-aided projects in school education has become a tradition. The duration of such projects has lengthened and the number of donors has increased, yet the results remain far from satisfactory. Ironically, the very failure to achieve expected educational outcomes has been used as justification by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology to seek ever-new foreign-assisted projects.

However, Shiva Kumar Sapkota, joint secretary and spokesperson at the ministry’s Planning and Monitoring Division, argues that this should not be viewed negatively. “If donors themselves say they want to help improve your education sector and introduce new reforms, can we really say no after having become part of a global village?” he asks.

According to the Red Book of the Ministry of Finance, in the past decade alone, Rs 587 billion has been spent through the Ministry of Education on education projects, excluding regular expenditures such as salaries, allowances, and administrative costs. Of this amount, Rs 200 billion was spent from donor-funded loans and grants. Despite such massive spending and the continuation of foreign aid in education, the quality of public education has not improved. Instead, learning outcomes have continued to decline.

Neither the Ministry of Education nor any other agency has accurate data on how much foreign assistance Nepal has received over the four-and-a-half decades of continuous education projects. The Ministry of Finance’s Aid Management Platform also lacks comprehensive records. The platform only contains data from January 2000 to December 2025. According to this data, 112 donor agencies committed more than Rs 576 billion (over USD 4 billion at the current exchange rates) for nearly 500 education-related projects. Of this, more than Rs 432 billion (over USD 3 billion) has already been spent. Records from 1981 to 2000 have not been entered into the Aid Management Platform.

Number of donor -supported educational program

Educationist Kusiyait argues that reliance on donor-funded projects for policy formulation, budget allocation, and program implementation has prevented Nepal from achieving expected results. “From policy formulation to implementation, either bureaucrats dominate or donors do. There has been no space to genuinely work toward improving educational standards,” he says.

Donor dominance in education

Trapped in a web of projects since the formation of the education commission, Nepal’s education sector continues to rely on donor-funded initiatives for policy-making, master planning, curriculum development, classroom and school building construction, teacher training, and technology expansion. Since 1980, major donors such as UNESCO, UNDP, the World Bank, UNICEF, Denmark, Japan, ADB, the European Commission, Norway, Finland, Australia, the UK aid agency, the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), the Global Partnership for Education, the European Union, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) have expanded project assistance.

According to UNESCO’s “Education Budget in Nepal” report published in 2022, these agencies remain the principal donors investing in Nepal’s public education. Among them, the World Bank and ADB primarily provide loans rather than grants.

Donors not only provide loans and grants in the name of uplifting Nepal’s education but also recommend policy agendas that often do not align with the country’s rural context. Education researcher Regmi notes in his research paper that since the primary education project and the Basic and Primary Education Master Plan – implemented with World Bank support in the mid-1980s – the government’s role in educational activities and decision-making has steadily weakened. Between mid-December 1981 and mid-October 2017, the World Bank alone spent Rs 129 billion (USD 897.8 million at current exchange rates) on Nepal’s public education in the form of loans and grants. The Bank continues its support under the SESP project as well.

Another educationist, Bidyanath Koirala, says the government’s weak position vis-à-vis donors, has prevented timely quality improvement. “So far, we have spent money mainly on building classrooms and increasing enrollment, but we failed to produce human resources based on market demand. That’s where we went wrong,” he says. “Today, we lack teaching skills, curricula, and teachers that can connect education with the market.”

However, Joint Secretary and Spokesperson Sapkota disagrees with claims that donors directly influence Nepal’s education policies and programs. “Donors have global principles related to human rights and good governance. We sign project agreements and implement them based on our needs. I don’t think donor influence is that direct,” he says. “If such influence exists, it reflects weaknesses in our own leadership and decision-making processes. Donors cannot be blamed.”

Declining outcomes

If the results of Grade 10 examinations (formerly SLC, now SEE) are taken as the sole indicator, the return on the massive investments made over the past four-and-a-half decades is far from satisfactory. An analysis of Grade 10 results over the past two decades shows that instead of improving in line with investment, outcomes have actually deteriorated.

According to records from the Ministry of Education, only 46.51 percent of students nationwide passed the SLC examination in the 2062 BS academic year. The pass rate improved to 68.47 percent in 2065 BS but then declined again. In the 2071 SLC examination, the last to be held under that system, only 47.43 percent of examinees passed.

After 2072 (2015), the letter grading system was introduced and the examination was renamed the Secondary Education Examination (SEE). While practical marks have made the overall pass rate appear nearly double that of the SLC era, performance in mathematics remains particularly weak. In last year’s SEE results, of the 167,597 students classified as “non-graded” (fail), as many as 128,215 failed mathematics alone. According to the Office of the Controller of Examinations, the number of students failing in English, science and technology, the theoretical paper of Nepali, social studies, and economics stood at 80,672; 79,271; 54,735; 53,186; and 42,150 respectively.

Although SEE results for the 2081 BS academic year showed some improvement compared to the previous year, the overall pass rate (61.81 percent) was still lower than that of 2065 BS.

Iframe for SLC & SEE result

The inability to achieve result-oriented outcomes in the education sector has also been pointed out by the 62nd Annual Report (2082 BS) of the Office of the Auditor General. At the Grade 8 level, the target was to raise average learning achievement scores in mathematics, English, and science to 63, but progress reached only 26, 25, and 28, respectively. In Nepali, against a target score of 66, only 40 was achieved. Similarly, the goal of increasing the proportion of students studying technical subjects at the secondary level to 30 percent was met by only 2.7 percent.

In the same year, learning indicators for Nepali and English in Grade 5, as well as indicators for Grade 8, failed to meet their respective targets. In fiscal year 2080/81 BS (2023/24), the target was to raise enrollment at the basic level (Grades 1–8) to 99 percent, but progress reached only 95.1 percent. Likewise, the target of raising the gross enrollment rate in higher education to 22 percent resulted in an achievement of only 20.05 percent.

Educationist Kusiyait analyzes the situation as follows: “Donors only care that their money is spent and that their own citizens get jobs in Nepal; they are not concerned about quality. On our side, there has been a lack of good governance, management, and leadership capable of making the right decisions. And, we are now living with the consequences.”

Interestingly, studies conducted by donor agencies themselves reveal that donor-funded investments have failed to improve learning outcomes.

A World Bank study has pointed out that while the SSDP project increased student access to schools in Nepal, it failed to achieve targeted learning outcomes in mathematics and science at the Grade 8 level. According to the World Bank’s baseline survey, the pass rate in mathematics in 2017 stood at 46.25 percent, and 43.81 percent in science. However, after the implementation of SSDP, these rates declined in 2020 to 32.1 percent in mathematics and 37.8 percent in science.

Similarly, a study titled “Failed Teacher Training Programs in Nepal,” published in the World Bank Economic Review Journal on 8 July 2024, found that teacher training provided under SSDP to mathematics and science teachers of Grades 9 and 10 resulted in little to no improvement in student learning. These findings clearly show that donor investments have failed to contribute meaningfully to improving student learning outcomes.

Private schools which receive neither government resources nor donor funding have delivered better results than public schools that benefit from state funding and foreign aid. Community schools, in fact, are stronger than many private schools in terms of infrastructure, human resources, and physical facilities. However, studies show that excessive politicization within these schools has adversely affected academic quality, making them weaker than private institutions.

A research paper published a year ago by Far-Western University supports this conclusion. In the paper, author Dasharath Shrestha concludes: “Despite being established with profit motives, parents prefer private schools because instruction is delivered in English, homework is assigned, regular assessments are conducted, co-curricular activities are encouraged, and sports are taught. The single most important reason for this preference is the politicization of community schools.”

Literacy has risen, but not quality

Statistically, Nepal’s average literacy rate has improved to 76.2 percent, an increase 38 times higher than in 2011 BS (1954/55). According to a study titled “Education in Nepal” prepared by members of the National Education Commission, in 2011 BS, there were only 1,320 primary, secondary, and school-level institutions nationwide. At that time, the country had 3,524 teachers (3,461 male and just 63 female) and 72,291 students.

Over the past 70 years, the numerical growth in schools, teachers, and students has indeed been encouraging. According to last year’s economic survey, in the 2081 BS academic year, Nepal had 35,447 schools at the pre-primary, basic (Grades 1–8), and secondary (Grades 9–12) levels, serving 7,010,808 students with 279,585 teachers nationwide.

Despite such improvements in nationwide education statistics, the 2078 (2021) Census shows that Madhesh Province still ranks lowest in literacy, with nearly 36.5 percent of its population unable to recognize even alphabets. “Being classified as literate simply by recognizing alphabets and producing competitive human resources aligned with market demand are two very different things,” argues educationist Koirala. “This is the era of artificial intelligence and information technology; jobs are there. But our teachers’ results are limited to merely passing or failing students.”

Joint Secretary and Spokesperson Sapkota of the Ministry of Education considers the continuity of education programs itself to be a major achievement. “There is an economic crisis everywhere. In such a situation, being able to continue education-related programs and plans is in itself a big accomplishment,” he says. However, he also notes that 95 percent of the total annual education budget is spent on the continuation of old programs, staff salaries, allowances, and administrative activities, leaving little room for investment in quality education.

Weak implementation capacity

Thirty-two years ago (1992/93), total investment in education, including foreign aid, accounted for 8.5 percent of the national budget. With the launch of the “Education for All” campaign, this figure rose to 17.1 percent by 2008/09. Since then, allocations have steadily declined, reaching 10.75 percent in the current fiscal year.

Professor Bal Chandra Luitel, Dean of the School of Education at Kathmandu University, says that despite producing teachers through foreign loans and grants, learning outcomes remain unsatisfactory. “Donors fund curriculum reforms with good intentions, but classroom teaching still follows outdated methods. Teachers remain accustomed to old pedagogical practices,” he says. “Money is being spent, but teachers who pass training programs lack the self-awareness needed to implement curricula that have evolved over time.”

He further argues that universities have failed to produce the kind of school principals needed for today’s education system. “Universities do not produce principals capable of transforming education and leading schools effectively,” he says. According to Luitel, Kathmandu University alone produces about 25 qualified principals per year, while the country requires more than 35,000 competent school principals.

Undersecretary Ramesh Prasad Ghimire of the Ministry of Education also acknowledges that effective learning outcomes proportional to investment have not been achieved. “At the policy, legal, and budget formulation stages, we tend to be overly ambitious. When programs are designed without considering implementation capacity, even spending the allocated budget becomes a struggle,” he says.

Indeed, in fiscal year 2023/24, as many as 60 programs, including the National Education Reform Program listed in the Ministry of Education’s annual program, were not implemented at all. This clearly reflects the weak implementation capacity of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology and its mechanisms.

This inevitably raises a critical question: How can foreign grants and loans, taken year after year, ever become productive under such conditions?