KATHMANDU: Dirgha Raj Koirala is not an unfamiliar name among those interested in the educational and social history of Nepal. Dirgha Raj, the son of Bishnu Raj Koirala and Man Kumari, was born in Biratnagar on February 22, 1920.

Before he turned two years old, due to the deterioration of the relationship between Krishna Prasad Koirala, a key figure in Nepali political history, and the then Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher Rana, Bishnu Raj, a close relative of Krishna Prasad, was also forced into exile in India alongside Krishna Prasad. Forced to leave his birthplace with his father, Dirgha Raj spent his schooling years in India. After Chandra Shamsher’s death, the Koirala family was allowed to return to Nepal. Upon returning, Dirgha Raj studied up to B.A. at Tri-Chandra College.

Dirgha Raj’s deep connection with the education sector began when he became the founding Headmaster of the Public Middle School in Dharan. Subsequently, during the Rana period, he was appointed Deputy Director for education in the Eastern region. Having been involved in the education sector through the government for a long time, he also served as the Executive Chairman of the Agricultural Development Bank for eight years and retired from the post of Secretary.

After the restoration of multiparty democracy, when Girija Prasad Koirala became Prime Minister for the first time in 1991, Dirgha Raj was nominated as an advisor. The unmarried Dirgha Raj passed away in 2010 at the age of 90.

In 1951, the Rana regime in Nepal ended, and a multiparty democratic system was initiated. With this, Nepal entered the ‘modern era.’ Nepal’s relationship with the outside world expanded. The outside world began assisting in Nepal’s ‘development.’ In this sequence, at the request of the Government of Nepal, the American Government agreed to assist Nepal in sectors including education. Various projects were started. Nepalis began to be sent to America for training in the education sector and to pursue higher education.

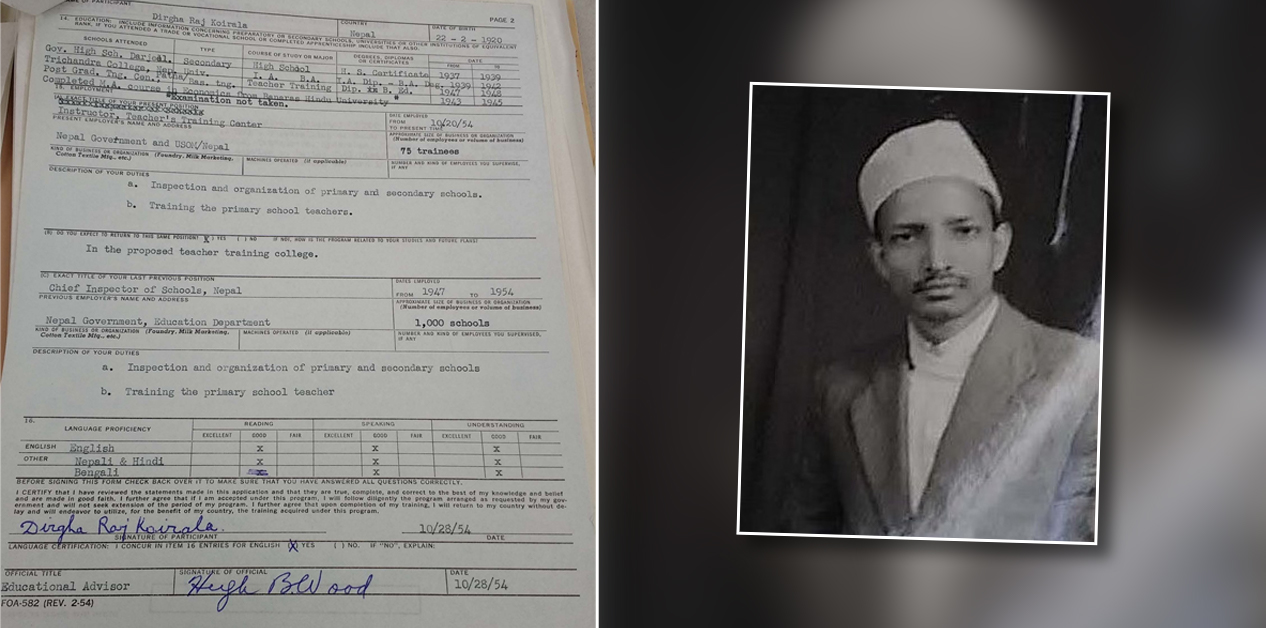

Dirgha Raj, who was working as the ‘Chief Inspector of Schools’ in the Department of Education, was also scheduled to go to America for studies. Although he was initially expected to study Teacher Education at the University of Oregon, he later returned to Nepal after obtaining an M.Ed. degree from the University of Ohio. A copy of the application form he filled out and his ‘autobiography’ (autobiography) when he went to study in America is safely preserved in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives at Stanford University in America.

This material, which was part of the collection of Nepal’s first foreign ‘Education Advisor,’ Hugh B. Wood (a Professor at the University of Oregon), later reached the Hoover Institution. In the course of researching Nepal’s education history, I spent a few months in 2017 at that institution. And, I made a copy of Dirgha Raj’s personal essay. The Nepali translation I made of that material, which was originally written in English, is presented here.

This article not only provides additional information about the story of Dirgha Raj Koirala’s youth and his thoughts, but also recounts some aspects of Nepal’s social (Sati system / polygamy system), political (Rana-subject relations / migration), and educational history.

Family Background

Writing something about oneself is a somewhat difficult task. It becomes even harder when there is very little to tell. Despite these difficulties, it is interesting and thrilling to look back at the past and contemplate the significant moments that have influenced one’s character and personality.

My mother used to tell me when I was young that my great-grandmother committed Sati after my great-grandfather died, leaving behind her children. At that time, my grandfather was only five years old. His elder brother raised him. That orphaned grandfather grew up and raised his eight daughters and three sons. He passed away in Banaras in 1919 at the age of 84.

My father (Bishnu Raj Koirala) was the youngest child of his father. As the number of family members increased, it became difficult to sustain the family only on the income from the land. Consequently, they left their ancestral home in the Eastern Hills of Nepal and moved towards the Eastern Terai, settling there. Our family was among the first batch of settlers in what is now Biratnagar town.

They cleared a dense jungle and established a settlement there about 50 years ago (that is, in the first decade of the 20th century).

I first saw the light of the world on February 22, 1922, on previously uncultivated land in Eastern Nepal, surrounded by jungle.

Looking into my father’s life story, it appears that various kinds of problems and sorrows befell him around the time of my birth. At that time, a political movement was raging in India. Mahatma Gandhi had already launched his Non-Cooperation Movement.

Our family was somewhat progressive and politically conscious. Our family raised some voices against the autocratic Rana regime, demanding an improvement in the economic and social condition of the suffering farmers. This angered the then Rana Prime Minister, Chandra Shamsher.

When I was about two years old, an arrest warrant was issued for my father and Krishna Prasad Koirala, the father of Matrika Prasad Koirala, the present Prime Minister of Nepal (with whom my father maintained a close relationship throughout his life). They fled to India, abandoning all their assets and possessions (which, at the current rate—1954—would be worth more than INR 500,000. The house, land, and possessions went to the government, and we became refugees forever. The government had announced a reward for anyone who arrested our fathers or helped in their arrest.

One night, in the biting cold of winter, our house was suddenly surrounded by police. Everyone was taken out; my mother had nothing more than a shawl to cover me and my elder brother. The police did not even allow her to take the metal cup I used for drinking milk; my mother later told me that they had to leave all their belongings behind.

This vindictive behavior of the then Rana Prime Minister towards our family forced us to leave our birthplace and seek refuge in India. After this tragic incident, my family wandered like nomads in various parts of North India. Friends occasionally provided some small help. My father moved from one place to another to make ends meet. Despite this poverty and hardship, my parents believed their children must be educated, and they tried to provide us with education at any cost.

At that time, I was almost oblivious to all these difficulties arising from the extreme poverty prevailing in our family, but now I can feel the seriousness of the situation then and the hard work my father did for us. All this has left an indelible mark on my mind and instilled in me a sense of responsibility towards children and dependents, even though I have not yet become a father.

Childhood and Education

Now I had grown up and was ready to go to school. My parents could not afford to send me to an expensive school. They had to look for a school where I could get a good education cheaply, and which would also help in building my character and personality.

After much thought, I was sent with my elder brother (Dhundi Raj Koirala) to the Bihar Vidyapeeth in Patna, known as Sadakat Ashram. This institution was run by nationalist workers of the Indian National Congress, and its head was Dr. Rajendra Prasad, who was the first president of India. He is also the longest serving president of India from 1950-62.

Around 1927, when I was eight years old, I was separated from my mother and father. However, I did not feel very lonely because my sibling brother, and my uncle’s son, Matrika Prasad Koirala, were also studying there with me.

Thus, my initial education began at a national institution in India during the British rule. I stayed in that school for two years. There were two blocks. One was for small children, and the other was for older boys. We had to work as well as study according to the schedule set by the school authorities. I received my first lesson in community life at this institution.

We students used to go together to bathe in the Ganga River, exercise together, have breakfast, eat lunch, and also hold assemblies together on special occasions.

Looking back at those past days, I feel thrilled now. Sometimes I wish I could go back to that childhood.

Here I want to mention a mischief we did to fulfill a childish wish. It was winter. The chickpea bushes were lush in the fields. In Bihar, there is a custom of lightly roasting and eating green chickpeas with the whole plant. This is called horaha. Eight or nine of us boys planned together and went to a nearby field. We chose a small piece of field with embankments all around and set it on fire. While half the chickpea bushes/shrubs were engulfed in fire, the owner of that field arrived carrying large sticks.

You can guess what the result was. The news of our mischief reached the Ashram authorities. As punishment, we were not given dinner, and the damage caused in the field had to be compensated by us, shared equally.

It was at Sadakat Ashram that I got the opportunity to meet Mahatma Gandhi for the first time. Gandhiji stayed at the Ashram for a few days.

Sitting cross-legged on the green lawn, he would teach the boys sitting around him. Those were truly golden days—carefree and enjoyable.

The place in North Bihar where our family was residing after the exile was hit by a big flood from the Koshi river. The flood washed away our homes; the land turned into a riverbed. Our families took the remaining belongings and headed towards Benares. And, I also had to leave Sadakat Ashram within two years. When I left the Ashram, I was proficient in the three things (reading, writing, and arithmetic). I also had some knowledge of the history and geography of India.

I completed my schooling in Banaras. During my stay of about eight years in Banaras, I studied in various schools there. While I was studying in grade 8, Maharaja Chandra Shamsher Rana of Nepal, who had banished our family, passed away. The Prime Minister who succeeded him, Bhim Shamsher, lifted the ban on our entry into Nepal.

Knowing this, I was extremely happy. I would now be able to go to my homeland, Nepal, which had been a mystery to me. I was impatient to visit my birthplace. I was able to step onto my homeland after about 15 years. After spending two weeks in my birthplace, I returned to Banaras to continue my studies. However, unfortunately, my mother died in 1936. After my mother’s death, I also fell ill. I was confined to bed for about six months.

After recovering slightly, I went to Darjeeling for a change of climate. I stayed with my brother (Dharanidhar Koirala; not a sibling), who was teaching at the local Government High School there. While staying there, I prepared for the Matriculation examination and took the exam from the same school in 1938. Thus, I completed my schooling from India without knowing much about Nepal or the Nepalis.

Return to Nepal

Being granted permission to return to Nepal was a great satisfaction for us. My father was eager to settle in Biratnagar. In 1938, my brother (Dhundi Raj) and I headed towards Kathmandu. I wanted to pursue further studies; my brother was looking for a job.

With my family’s return to Nepal, another domestic problem arose; the relationship between my father and us became strained.

After my mother’s death, my father had remarried. After the new marriage, my father stopped providing us with financial support. The marriage might have been okay for my father, but due to financial matters, it seemed inappropriate to me.

My father’s income was not good; he was not in a condition to bear the burden of us and this new relationship. Therefore, my brother and I tried to stand on our own feet and tried to reduce the burden on our father. In Kathmandu, I enrolled in Tri-Chandra College. There was no tuition fee for college studies. I started tutoring school children, and that income covered my living expenses in Kathmandu.

Having been raised, grown up, and educated in India, I was annoyed by the gloom/indifferent attitude of my classmates here; they socialized less, spoke less, and lived in isolation. For the first three or four months, it was difficult for me to adjust to the atmosphere and environment of Kathmandu. I knew very few people here. But gradually I made some friends; I started going out and socializing with them.

During my four years of study in Kathmandu, I only acquired theoretical book knowledge. There was no scope to delve deep into the imaginary side of life. Anyway, I received a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree in Humanities from Patna University in 1942. (At that time, Tri-Chandra College was affiliated with Patna University.)

However, my aspiration for higher studies remained. Due to the financial condition of the family, I could not continue my higher studies outside Nepal. Therefore, I decided to work for some time, save some money, and then continue further studies. Accordingly, as soon as the B.A. examination result came out (in May 1942), I applied for a job in the Kolkata (then Calcutta) Police.

Those were the days of World War II, in which India was also involved. At that time, the Congress had passed the ‘Quit India’ movement proposed by Gandhi and had plunged into the movement. There was confusion and unrest everywhere.

Fortunately, I got a temporary job in the Kolkata Police. I was appointed as a language instructor, and my job was to provide language training to European officers, sepoys (sergeants) of the Kolkata Armed Police. At that time, Kolkata was full of American soldiers, and the Japanese were bombing Kolkata. It was during this time that I got the opportunity to fly in an airplane for the first time in my life.

It was an enjoyable and delightful flight of about one hour over the Bay of Bengal and Kolkata city.

After working for about one year, I resigned from the job. Taking the money I had saved from work, I headed from Kolkata towards Banaras. I enrolled in M.A. in Economics at Banaras Hindu University. I studied as a regular student for two years and appeared in the final M.A. examination. But in the middle of the exams, one day I was suddenly arrested by the C.I.D. police of the Government of India. I was detained for interrogation under the recently implemented ‘Defense India Rule.’ I could not complete the entire examination. My dream of getting an M.A. degree remained unfulfilled. To be honest, that was the end of my student life.

University studies were over. After being released from custody, I went to Biratnagar. I started a school (Dharan Public Middle School) in Dharan, about 25 miles north of Biratnagar. Today, it is one of the best schools in Nepal. I worked there as the manager and headmaster for more than one year.

We built the school building by collecting donations. Local traders and other common people provided good cooperation in this public work. After the building was ready, I was sent to the center to inquire if government financial assistance could be obtained for the school’s operation.

In 1947, I came to Kathmandu during this process. I assured the government officials that the foundation of the school was strong and that it was eligible for government assistance. And, I also secured government assistance. At that time, I learned that a job for Deputy School Inspector was open, and I applied for the position.

After the interview, I was selected as the Deputy School Inspector for the Eastern region. Along with this, I was sent for post-graduate training at the Basic Education Training Center in the Bihar state of India. During the training, I got the opportunity to visit Sevagram (Gandhi Ashram/residence in Maharashtra) and other educational centers. I spent two months working at Sevagram.

In 1949, I got the privilege of participating in a UNESCO Seminar on Rural Adult Education held in Mysore. I got the opportunity to meet representatives from various countries for the first time in my life. This seminar, which lasted for about one month, gave me a good opportunity to enrich my imagination and understand the thinking trends of different countries.

Aspirations

In July 1950, my father passed away suddenly from a cerebral hemorrhage. His death was a severe blow to me. The responsibility of raising my widowed stepmother and five stepsisters fell upon me. In fact, at that time, I was considering leaving government service and starting a public institution (school?) in a suitable place outside the Kathmandu Valley. But, due to the added responsibility of caring for and raising my younger sisters after my father’s death, I abandoned that idea.

Just a few months after my father’s death, a popular revolution began in Nepal. The autocratic rule of the Ranas was swept away, and a democratic government was established. However, those of us who are in government are not completely satisfied with the current system of administration. We lack cooperation, coordination, readiness to serve, and unity of purpose, which a democratic government needs to start.

I believe that for any country to move forward, it is not possible unless there are some committed workers who dedicate themselves to the country’s interests. The tendency of our current generation is that no deserving youth wants to go to the interior/villages of the country.

He wants to stay with his urban friends and enjoy himself by creating his own circle. The members of that circle do not want to mix with the general public. Consequently, the suppressed, oppressed, ignorant masses always remain ignorant, and the educated individuals, separated from the masses, waste their knowledge and energy in useless drawing-room debates or political movements.

Therefore, the need of the hour is to first get trained ourselves and then train others who are worthy.

If, after becoming worthy ourselves, we ignore the needs of the common people and only aspire for our personal gain and progress, it is of no use; it does not benefit the nation. As our ancient sages have said, it is necessary for us to always be committed to serving others without expecting any reward.

We have a verse in our morning prayer, which says, ‘O God, I do not wish for any kingdom to rule; nor do I wish to go to heaven or desire rebirth. I only wish to destroy and remove the sorrow and suffering of the entire miserable humankind.’ It is my wish and desire that I can serve the nation with this spirit and help my ordinary brothers and sisters become honest, sincere, disciplined, and selfless citizens of the human world.