The decline of cadre judges in the Supreme Court poses a risk to the quality of justice delivery

KATHMANDU: For the next decade, the Supreme Court’s helm will be continuously steered by a succession of Chief Justices appointed directly from the legal practitioner background. After the retirement of the Chief Justice, Bishowambhar Prasad Shrestha, who rose through the ranks starting as a District Judge, it was a long wait before a ‘cadre judge’ (one who entered through the judicial service) got a turn to lead the judiciary.

The Constitution mandates 21 posts for judges, including the Chief Justice, in the Supreme Court. However, currently, only 19 judges, including the Chief Justice, are appointed. The provision stipulates that the Chief Justice is appointed on the basis of seniority.

Chief Justice Prakash Man Singh Raut, appointed on October 6, 2024, will retire on March 31, 2026. Following Raut, the judiciary will be led by Sapana Pradhan Malla, Kumar Regmi, and Hari Prasad Phuyal, in terms of seniority. Only after them, in late 2035, will Nahakul Subedi, who came from the judicial service, become the Chief Justice. Raut, Malla, Regmi, and Phuyal were all appointed directly to the Supreme Court from a legal practitioner background.

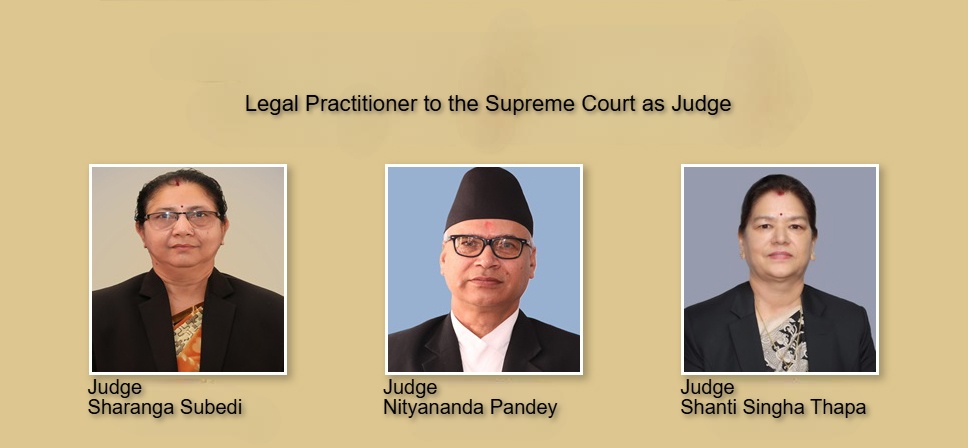

Besides these, the following are currently serving as Supreme Court judges: Til Prasad Shrestha, Binod Sharma, Sharanga Subedi, Abdulaziz Musalman, Mahesh Sharma Paudel, Tek Prasad Dhungana, Sunil Kumar Pokharel, Bal Krishna Dhakal, Nripa Dhwoj Niroula, Nityananda Pandey, Meghraj Pokharel, Shrikant Paudel, and Shanti Singh Thapa. Excluding Til Prasad, Binod, Mahesh, Tek Prasad, Nripadhwaj, and Shrikant, all others have a background as legal practitioners.

Sub-section 2 of Article 129 of the Constitution states, “The President shall appoint the Chief Justice on the recommendation of the Constitutional Council and other Supreme Court judges on the recommendation of the Judicial Council.” Sub-sections 3 and 4 of the same article stipulate that “a person who has worked as a judge of the Supreme Court for at least three years shall be eligible for appointment to the post of Chief Justice, and the term of office shall be six years.”

Regarding the appointment of judges, the Constitution states, “A Nepali citizen who has a bachelor’s degree in law and has worked as a chief judge or a judge of a high court for at least five years, or who has a bachelor’s degree in law and has worked continuously for at least 15 years as a senior advocate or advocate, or who has continuously worked in the field of justice or law for at least 15 years and earned recognition as a distinguished legal expert, or who has worked for at least 12 years in the Gazetted First Class or above position of the judicial service shall be considered eligible for appointment to the post of judge of the Supreme Court.”

Rooted political interference

Former judges assess that the decline in the appointment of cadre judges is due to political interference in the Constitutional Council, which recommends the appointment of the Chief Justice, and the Judicial Council, which recommends the appointment of judges.

The Constitution itself provides for a Constitutional Council chaired by the Prime Minister to recommend the appointment of the Chief Justice. As per the constitutional provision, the Constitutional Council recommends the appointment of the Chief Justice. The Constitutional Council, formed under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister, has provisions for the Speaker, the Chairperson of the National Assembly, the Leader of the Opposition, and the Deputy Speaker to be members. The recommendation for the appointment of judges is made by the Judicial Council itself. The Judicial Council, which appoints judges, is chaired by the Chief Justice, with the Law Minister, the senior-most Supreme Court judge, a senior advocate appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, and a representative of the Nepal Bar Association designated as members.

Judges in the Supreme Court and High Courts are appointed in two ways: one through the Judicial Service (including government attorneys) and the other through the legal profession. Appointments from the legal profession are also referred to as “appointments from the Bar.”

Krishna Jung Rayamajhi, a former Supreme Court Judge, states that even though they come from a justice and law background, the performance of cadre judges appears comparatively better. He comments that judges who enter through political appointments may have less experience and may have to face external pressure (from those who appointed them).

“It is not that everyone who comes from the Bar is weak, but not everyone who comes from the Cadre is good either!” Rayamajhi himself was appointed to the regional court from a legal practitioner background in the fiscal year 1981/82 and reached the Supreme Court. When someone is brought directly to the Supreme Court, they have less experience in resolving cases. Judicial reform can be achieved by learning from the lower courts,” said Rayamajhi.

A judge who chose to withhold his name currently working in the Supreme Court who was appointed from the judicial service also states that it is not appropriate to bring individuals directly from the Bar to the Supreme Court and make them the Chief Justice. Arguing that individuals from the Bar show weaknesses in the management aspects like case management and staff, he contends that bringing judges who have already handled cases in the High Court to the Supreme Court would be much easier.

“Judges should be appointed only by looking at the date the legal practitioner obtained their license and the date the cadre entered the service,” said the judge, who chose to withhold his name. “If judges can be brought in based on competence, no one could point a finger at the leadership capacity of the judiciary.”

Secretary General and Senior Advocate Kedar Prasad Koirala of the Nepal Bar Association claims that all judges who reach the Supreme Court from a legal practitioner background are excellent. Stating that the Nepal Bar’s demand is for half of the appointments to be represented by the Bar, he asserts that the background should not matter regarding the competency of a justice.

“The person who can render justice to a case in the realm of justice should be a judge. There should not be a restriction specifying who it must be. It should be kept open. One cannot be excluded by pointing to the other,” said Secretary General Koirala. He further adds that it is wrong to attach a political color to anyone after they become a judge.

According to Judicial Council statistics, since the new Constitution was promulgated in 2015, up until September 2 of this year, at least 71.5 percent of judges who reached the Supreme Court were promoted from the High Court. These include individuals from both the legal profession and the judicial service. Judges appointed directly to the Supreme Court from the legal profession make up 28.5 percent.

Rampyari Sunuwar, spokesperson for the Judicial Council, indicates that in the 10 years since the implementation of federalism, 45 percent of judges in the High Court were promoted from the District Judge rank, 21.5 percent came from the judicial service (staff), and 33.5 percent were appointed from the legal profession.

Why cadre judges?

Ek Raj Acharya, the then Chief Judge of the Jumla Appellate Court, resigned in 2013, while two years remained in his term. He resigned after his junior, Cholendra Shumsher Rana, was appointed as a Supreme Court Judge.

“Lawyers and professors should also be allowed to be judges, but the current system has kept cadre judges very far away,” said Keshari Pandit, former Chief Judge of the Appellate Court.

Acharya states that the practice of promoting a junior individual from the Nepal Bar by bypassing seniors in the judicial service is wrong. “Individuals from the legal profession should be brought to the Supreme Court not all at once, but through the High Court, which teaches proficiency in resolving cases,” says Acharya. “It’s not that only cadre individuals should be judges. However, competence should be the main basis for appointment.”

The lack of cadre judges in the leadership of the judiciary is due to appointments being made directly from the Nepal Bar with the aim of eventually becoming the Chief Justice. Former Chief Judge Acharya states that this anomaly prevails due to the lack of criteria for selecting judges.

“The practice of cadres retiring due to age without getting an opportunity, while those from the Bar go directly to the Supreme Court while they are still young, must be ended,” Acharya further added.

Keshari Pandit, former Chief Judge of the Appellate Court, states that it is ironic that the journey of a person who becomes a District Judge when their age and service period are ending appears long for reaching the Supreme Court, while a legal practitioner reaches the Supreme Court directly. Stating that in India, a person is eligible to become a district judge only after working for five levels, Pandit says, “Lawyers and professors should also be allowed to be judges, but the current system has kept cadre judges very far away.”

Pandit himself was deprived of reaching the Supreme Court despite having the qualifications and capacity. He states that cadre judges are necessary to show the possibility and hope of reaching the leadership of the Supreme Court to judges working at the district level. Pandit argues that otherwise, the gap between the lower and Supreme Courts will continue to widen.

The Former Judges Forum, Nepal, has also been emphasizing the appointment of the Chief Justice from among career judges. Stating that district judges who entered the judicial service through the Public Service Commission and have accumulated long experience in the administration of justice are being deprived of judgeship and that favoritism is being promoted over merit, the Forum issued a statement on June 20, 2024. The statement, issued by the Forum chaired by Top Bahadur Singh, read, “It is clear that the plot to recommend individuals outside the judicial service to the High Court will discourage incumbent District Judges.”

Future chief justices

The current Chief Justice Raut will lead the judiciary until March 31, 2026. Active as a legal practitioner since the fiscal year 1982/83, he entered the Supreme Court in the fiscal year 2015/16.

Following Raut’s retirement, Sapana Pradhan Malla will take over the leadership of the judiciary in March next year. She will be the country’s second female Chief Justice. Having worked as a legal counsel for about 25 years since the fiscal year 1986/87 and serving as a Constituent Assembly member, she was appointed as a Supreme Court judge on August 2, 2015. She will remain the head of the judiciary until 2028.

Based on seniority, Justice Kumar Regmi will take the reins of the judiciary after Malla. Regmi, who was appointed as a judge on April 19, 2019, after working as a senior advocate, will be the country’s Chief Justice until 2031.

The current Chief Justice Raut will lead the judiciary until March 31, 2026. Active as a legal practitioner since the fiscal year 1982/83, he entered the Supreme Court in the fiscal year 2015/16.

The turn after that belongs to Hari Prasad Phuyal. He will lead the judiciary until 2035. He was appointed as a Supreme Court Judge on April 19, 2019, having previously served as a legal practitioner and Attorney General.

After him, Nahakul Subedi, from a cadre background, will become the Chief Justice. He will hold the chief position for nearly nine months, until 2036. Subedi, who had experience as the Chief Registrar of the Supreme Court and Chief Judge of a High Court, was appointed as a Supreme Court Judge on April 19, 2021.

Following that, Nripa Dhwoj Niroula will lead the judiciary for nearly one and a half months in 2036. Niroula became a judge on October 31, 2024, after serving as Registrar of the Appellate Court, Secretary of the Judicial Council, and Chief Registrar of the Supreme Court. Since currently employed judges will retire midway due to age limits, the next Chief Justice after Niroula has not yet been determined.