How astute Nepali officials used local testimonies, map discrepancies, and unwavering perseverance over 10 years to successfully challenge the British and regain a crucial segment of the Mechi River border.

KATHMANDU: ‘We get to see the special, miraculous play of the autumn sun in the hide-and-seek of red and yellow colors on our high Himalayan peaks. Such a sight can be witnessed on all the snow peaks like Machhapuchhre, Annapurna, Dhaulagiri, Manaslu, and Makalu. However, the Antu experience in Ilam holds a special place in my memory. While viewing the ascending rising sun by gazing eastward from Antu Hill, one must not forget to look at the successive pours of orange, golden, and silver hues on the Kanchenjunga snow peak behind one’s back. If we miss it even for a moment, we are left with great regret.’

Dr. Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha

Such an incomparable place was absorbed into Sikkim following the 1816 Sugauli Treaty. Had Nepal’s officials not demonstrated shrewd diplomacy, this treasured land would not belong to Nepal today. To witness the breathtaking vista described by Dr. Shrestha, one would have been forced to travel across the border into what was then Mughlan.

The story of how this territory was regained is a remarkable tale:

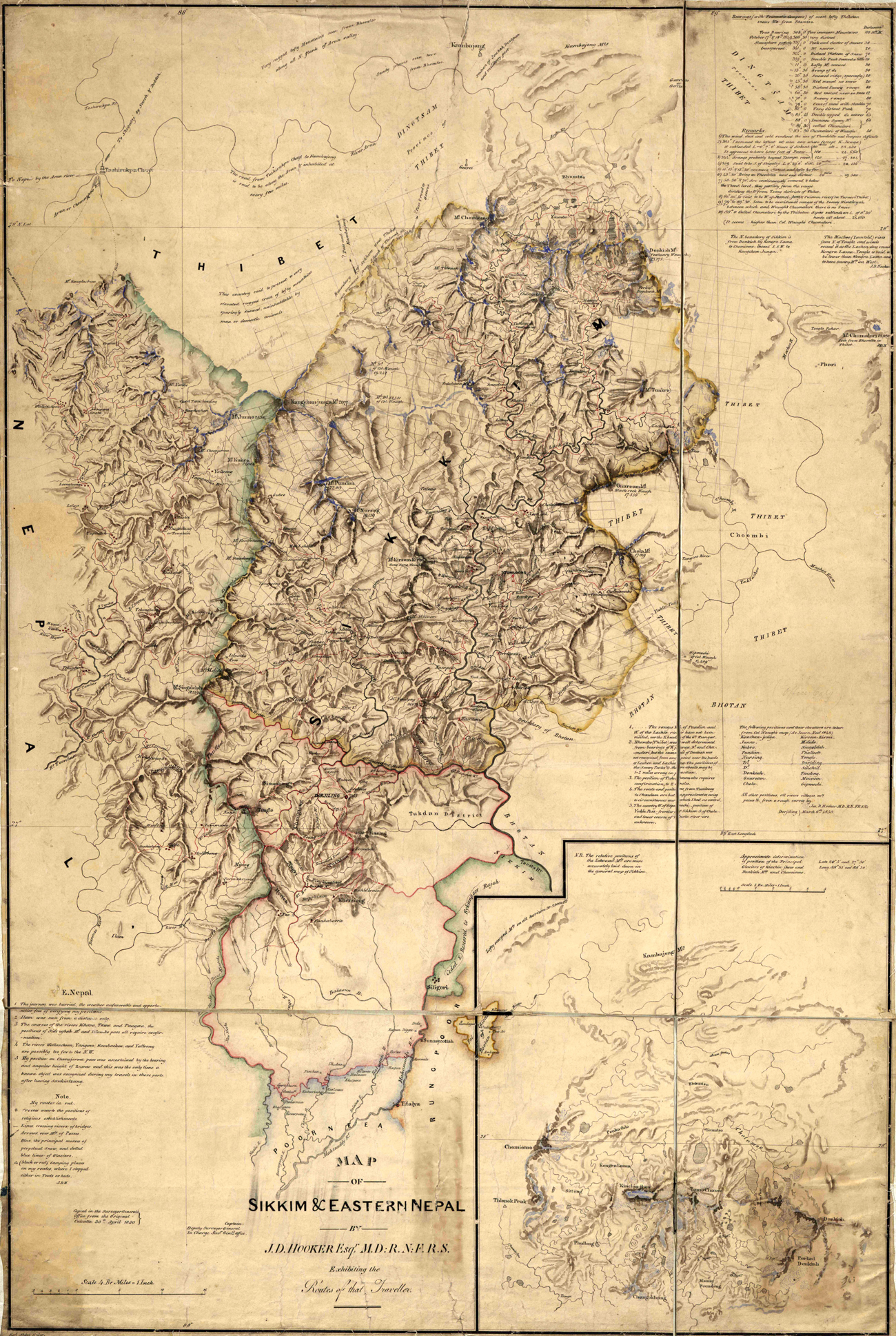

After the Sugauli Treaty, the British started hastily drawing the map of the border with Nepal. In this process, while drawing Nepal’s border with Sikkim, they labeled the Siddhi Khola as the Mechi River and pushed Antu into the Sikkim side. In doing so, 45 square kilometers of land, or about 37 percent of the Bhaktapur district area, which is now called Shree Antu and Samalbung, went to the other side.

Around 1826/1827, the King of Sikkim assassinated his prime minister and maternal uncle. Following this, high-ranking officials, including the Kaji, fled to Ilam with 800 families of Lepcha and Limbu people and began attacking Sikkim from there.

During the Sugauli Treaty, the British had seized a lot of land from Nepal for themselves. The hills east of the Mechi were given to Sikkim. In that treaty, a condition was imposed on Nepal that any border dispute with Sikkim must be resolved according to the British decision. About one year after the Sugauli Treaty, they signed a treaty with Sikkim, imposing the same condition on Sikkim—that any border dispute with Nepal must be resolved according to the British decision. Based on this, Sikkim filed a complaint with the British, claiming that Nepal had encroached upon the border at Antu.

Following this, the British dispatched Captain William Lloyd in 1828 to resolve this border dispute. In the winter of that year, he and his colleague, J. W. Grant, traveled deep into Sikkim under this pretext (it was during this trip that they determined Darjeeling would be suitable for the British to establish a sanatorium). They concluded that Nepal had encroached on the border at Antu and submitted a report.

A few years later, in 1834/1835, Captain Haribhakta from Ilam sent a dispatch to Kantipur claiming that the British had marked the border in the wrong location.

Nepal wrote to the British Ambassador, Hodgson, about this matter. When Hodgson inquired with Major Latter, the British officer stationed in the east, Latter replied that Captain Hari Bhakta had exaggerated the difference in his report.

The Mechi River, the eastern border river, does not originate from the Himalayas in the same way the Mahakali, the western border river, does. The Mechi River ends roughly halfway along the north-south border in the east. At the spot where this river terminates, there are three streams: Kechi, Mechi, and Siddhi.

The British asserted that these three distinct streams—Kechi, Mechi, and Siddhi—were, in fact, the same river. When the captain questioned the local residents about this claim towards 1835, they firmly refuted it, stating, “Siddhi is Siddhi, Mechi is Mechi, and Kechi is Kechi. We previously confirmed that Siddhi is Siddhi and Mechi is Mechi. No one has the authority to call Siddhi the Mechi, or the Mechi the Siddhi. Even in Sikkim, the stream that flows eastward from below Antu Danda and converges near the main Nagari road is known as Kechi. The river to its west is called Mechi. Furthermore, the stream to the west of Antu (Vanatu, as it was known then) Danda is unequivocally designated as Siddhi.”

Hari Bhakta then measured the distance between the sources of the Siddhi and Mechi rivers and found it to be 225 cubits.

Major Latter was in Sikkim at that time. After he returned, Captain Hari Bhakta prepared to meet Major Latter with witnesses who knew that Kechi, Mechi, and Siddhi were separate. He promised Bhimsen Thapa, “If, during a friendly and firm discussion with Major Latter—one that does not become too heated—we face any difficulty, I shall proceed to establish the boundary as per your command and instruction. If the difficulties are too great, I shall write and respectfully submit the matter.”

The phrase used by the captain, “If, during a friendly and firm discussion—one that does not become too heated—we face any difficulty,” is important. It shows that the Nepali at that time sought a resolution in a harmonious atmosphere, without conflict, in a way that would prevent the loss of Nepali territory.

The Nepal Court had commanded Captain Hari Bhakta to go and inspect the border. One document states, “He succumbed to his fate.” Based on this, it can be guessed that Hari Bhakta passed away.

For some time after this, it is unknown what happened regarding this matter. About two years later, in 1837, Nepali officials stationed in Ilam—Lakshhyabir Shahi, Hemdal Thapa, and Udayanand Pandit—traveled to Naxalbari in India, across the current Kakarbhitta, to meet and talk with the Saheeb (he is referred to as a Colonel). Captain Latter from the Nepal-Anglo War was a major until two years prior. This Saheeb, who is now a colonel, could be the same Latter. After that, they went to inspect the course of both rivers from the confluence of the Siddhi and Mechi. After inspecting the courses, they went to Nakkalbanda again for discussions. At that time, the colonel showed them a map and said, “There is more water in the western river than the eastern river, and the boundary line on the map is also drawn along the western river.”

In rebuttal, the Nepali officials said, “That map was not created by including people from both sides; the Saheeb must have brought his own people from the Sikkim side. The people of Sikkim cannot call the Siddhi the Mechi. The Mechi is on the eastern side. According to the Lalmohar (Royal Red Seal) and Tamrapatra (an inscription on a copper plate, which has been historically used in the Indian subcontinent to record important information like royal land grants, decrees, and genealogies) issued by the King long ago, the west of the Mechi was the jurisdiction of Chainpur. There was also a settlement between the Siddhi and Mechi. Taxes collected from there were submitted to Chainpur. Therefore, further investigation should be conducted on this matter.”

The Colonel then summoned the local landlord, Yekunda Kaji, and asked him, “Was there a settlement between the two rivers before, or not? Did you collect the tax or not?” In response, the Kazi said, “There were four or five houses settled between the Mechi and Siddhi, and I used to submit the tax from there to Chainpur. The river on the west side is the Siddhi. The Mechi is on the eastern side.”

After hearing this, the colonel asked if there were any people who had settled between the two rivers long ago. The Nepali officials replied, “One person has arrived here, and another is in the hills.” As requested by the Saheeb, the person in the hills was sent for, and Jangmo Lapcha, an 85- or 90-year-old man who had traveled to Nakkalbanda, was presented to the Colonel the next day. He stated that he had lived and cultivated land on and between the two rivers for about sixty years. He also said that the river to the east of Antu Danda is the Mechi and the river to the west is the Siddhi. The Captain Latter recorded his statement and sent him away.

Then Captain Latter asked Yekunda Kaji again, “Last year, when you were the landlord east of the Mechi, why did you not mention the collection of tax money from the settlements on Antu Hill and its submission to Chainpur?”

“I told you everything you asked last year. You did not ask about this matter, so I did not mention it. Now you have asked, so I have told you,” Yekunda replied.

“Can you swear on your religion regarding all this?” Colonel Latter asked.

“Why wouldn’t I be able to swear on my religion about what is true? I can,” he replied.

After this exchange, Colonel Latter asked if the Nepali officials had any other witnesses. The Nepali officials replied, “All people, young and old, know that this is the Mechi and that is the Siddhi. If you need them, we can bring two or four hundred people.” Colonel then said, “In that case, bring four or five more people of the Lapcha caste—who previously lived on the Antu hill but have not yet arrived here, out of the two original settlers—within 5 days. We will interrogate them.”

The Nepali officials agreed to call those people.

The Nepali officials stationed in Ilam did not expect that after hearing the testimony of those witnesses, the British would send the details to their headquarters and only demarcate the border upon receiving the order from there. They promised Bhimsen Thapa that they would not act against the interests of Nepal.

The British sent the case to the headquarters. One year after taking Darjeeling from the king of Sikkim, the British resident sent more than 14 questions to the Nepal government, insisting that the land belonged to Sikkim.

Nepal prepared its reply to this letter in 1837. The reply addressed the points one by one.

First

In response to the resident’s claim that the border demarcation was final because the Nepal court had not filed a complaint that the demarcation was incorrect, Nepal stated that the demarcation was not yet final. Nepal provided the following reason: The treaty states that the land east of the Mechi River belongs to the company’s government, and the land west of the Mechi River belongs to the Nepal government. Knowing that the Mechi was the boundary, Sikkim had filed a complaint with the Resident claiming that Nepal was trying to close the old course and create a new course. At that time, the Resident had asked Nepal to prepare people to debate with Sikkim. In response, Nepal had already asked why they should go to question Sikkim when their treaty was with the Company. Therefore, Nepal had indeed complained.

Second

The Resident had written that the Nepali Amin (physical measurer and documenter of land, which forms the basis for legal land records) stationed in Ilam, Udayanand, neither filed a complaint nor proved his complaint. In response, the Nepal Court said, “Udayanand has sent us a detailed letter about his conversation with the English Colonel. If he had not complained, why would he have sent it? Everything is clear on the map, which the resident must have also seen.”

Third

“What Hari Bhakta said is what the people say. It is true that he did what he could. He and Udayanand have submitted the map papers they drew to our presence. This matter is clear in those as well.”

Fourth

The British had asked Nepal to prove its claim. In response, Nepal said, “Such witnesses as were found have been sent through Udayanand.”

Fifth

In response to the resident’s claim that the new Amin sent by the court to replace Hari Bhakta knew nothing about the issue, Nepal said, “Even if personnel change, the documents and knowledgeable people are still here.”

Sixth

In response to the resident’s note that Sikkim delayed sending a lawyer this year to finalize the matter and Nepal had delayed last year, Nepal accepted that there had been a delay from both sides. However, Nepal hoped that people from both sides would go and the boundary that was established with the company previously would be confirmed.

“The residents who know that Sikkim changed the long-established name of the Mechi by removing stones piled on the Mechi and piling stones on the Siddhi to rename the Siddhi as Mechi are still there.”

Seventh

It seems Nepal had requested a re-examination of the border. In response, the Resident Sir said that if there were no new witnesses to prove Nepal’s claim, re-examining it would be useless. The resident also stated that all witnesses on Udayanand’s side had been present during the previous border demarcation. Nepal countered by asking why, if that were true, Udayanand would have had knowledgeable people make statements and send them to the Nepal Court claiming the border was incorrect. Nepal offered to send the statements they had made to the resident if needed.

Eighth

At this point, only thanks were given to the Resident.

Ninth

The Resident had written that the dispute was over a hill called Antu between two rivers. The river on the west side of these rivers is called Mechi by the Sikkimese and Siddhi by the Nepali. The river on the east side is called Kechi by the Sikkimese and Mechi by the Nepali. When questioned about which one is the real Mechi River, the answer received was that the larger river is the Mechi.

In response, Nepal reiterated that the eastern river is the Mechi and the western river is the Siddhi.

Tenth

The Resident had asserted that according to the provision of the Sugauli Treaty, when Jayanta Khatri left the Nagari fort and came to Nepal, he settled west of the river the Nepali called Siddhi. This proved that this river was considered the original Mechi during the war. In response, Nepal said, “A person settles where it is convenient. Jayanta Khatri initially settled at the Karphok fort. Later, he arranged for land and moved to the Ilam Gadhi barracks. Where one settles does not determine the border. It is determined according to what is stated in the treaty. The Mechi is clearly written in the agreement. The Resident Sir should clearly understand how the Siddhi can be considered the Mechi based on what the Surveyor Balu Sir (John Peter Boileau) had said.”

Eleventh

The Resident Sir had said that when Captain Lloyd went to see which of the Siddhi and Mechi rivers was larger, he had asked Udayanand to accompany him. At that time, Udayanand had refused, saying he was old and weak, and did not go with Lloyd. He had sent Bhaktabir Thapa and Durja Singh Thapa instead. The Resident Saheeb said that they determined that the western river was the real Mechi because it had more water. In response, Nepal said, “The long-established name would not likely be changed just because the western river has more water and they determined it to be the original Mechi River. The name of the Mechi that has been in use since ancient times will not likely be changed based on current claims. The original name will be ratified.”

Twelfth

To claim that the Siddhi River is the border between Nepal and Sikkim, the Resident wrote that when British personnel were sent to find the source of the Mechi to determine the border of Sikkim as per the government’s order, they fixed the border at the western river, which the Nepali call Siddhi. Jayanta Khatri did not go when he was called. In today’s maps, the Sikkimese and some Nepali call the eastern river the Chhoti Mechi and the western river the Badi Mechi.

Regarding this, Nepal said, “Jayanta Khatri should have gone. He did not go. He also did not submit a request about this to our presence. He was negligent.’ Because his death was near, he died shortly after.’ Therefore, understand that the Amin of Sikkim must have been alone when he wrote the report at that time. There is absolutely no Small Mechi and Large Mechi. There is only one Mechi. All the residents there know this.”

Thirteenth

The British Resident had written that Dehan Sir, on the order of Major Latter, had piled up stones at various places along the bank of the western river to establish the boundary. Later, those who had fled from Sikkim damaged the piles, built houses in the disputed area, and claimed that the land between the two rivers belonged to Nepal. This was known from the statements of those very Sikkimese who had fled earlier. Lloyd’s judgment confirmed that there were no houses or farms in that area before.

“It is true that stones were piled up on both sides of the Mechi bank. Later, the Sikkimese uprooted the boundary bamboo planted by Balu and tried to block the old course of the Mechi and divert the water to a new course on the west side. When that failed, they started calling the Siddhi the Mechi. The Mechi has been on the eastern side since ancient times. They are wrongfully calling the Siddhi, which is within our border, the Mechi.”

After Nepal sent this reply, the British decided to conduct a third and final investigation. It was decided that Dr. Campbell, Assistant Resident for Nepal, Colonel Lloyd, and the lawyers from Nepal and Sikkim would conduct a field inspection. However, the King of Sikkim refused to send a lawyer in 1837, repeatedly stating that sending a lawyer was futile. In 1838, he finally replied to the British, saying, “You are the master who handles all the work; do as you see fit.” Before this, Lloyd, who had studied the border on behalf of the British, defended the King of Sikkim’s decision not to send a lawyer. He wrote, “The investigation had already been done twice. If Sikkim sends a lawyer, they will have to send 300 people. That would incur expenses, and since the area where they need to be sent is prone to malaria, the king has refused to send a lawyer.”

Lloyd himself was unenthusiastic about further investigation. He said, “Even if we conduct the investigation three thousand times, let alone a third time, the desired result will not be achieved.”

Lieutenant Colonel Lloyd, Campbell, and the Nepali team went to Mechi Gola in around January and February 1838 of the same year. They circled Antu Danda. They reached the source of the two rivers and went to Naxalbari and Nakkalbanda. When the Sikkimese king again refused to send a lawyer in Falgun, Lloyd and Campbell submitted separate reports to their government at that time. Based on that report, the British government declared:

The river furthest to the east of the two rivers is called the Mechi. Therefore, that river is the boundary river. Consequently, Antu Hill is determined to belong to Nepal.

In 1839, the British Governor sent a letter with the same content to his Resident in Nepal, Hodgson, and announced the order to transfer the area to Nepal. Hodgson informed the king about this. The king commanded Hemdal Thapa to make arrangements for settlement and development after the land came under Nepal’s possession.

In this way, the 45 square kilometer land that had been lost for some time was recovered by Nepal without a major conflict, and the beautiful place like Antu Hill became Nepal’s.