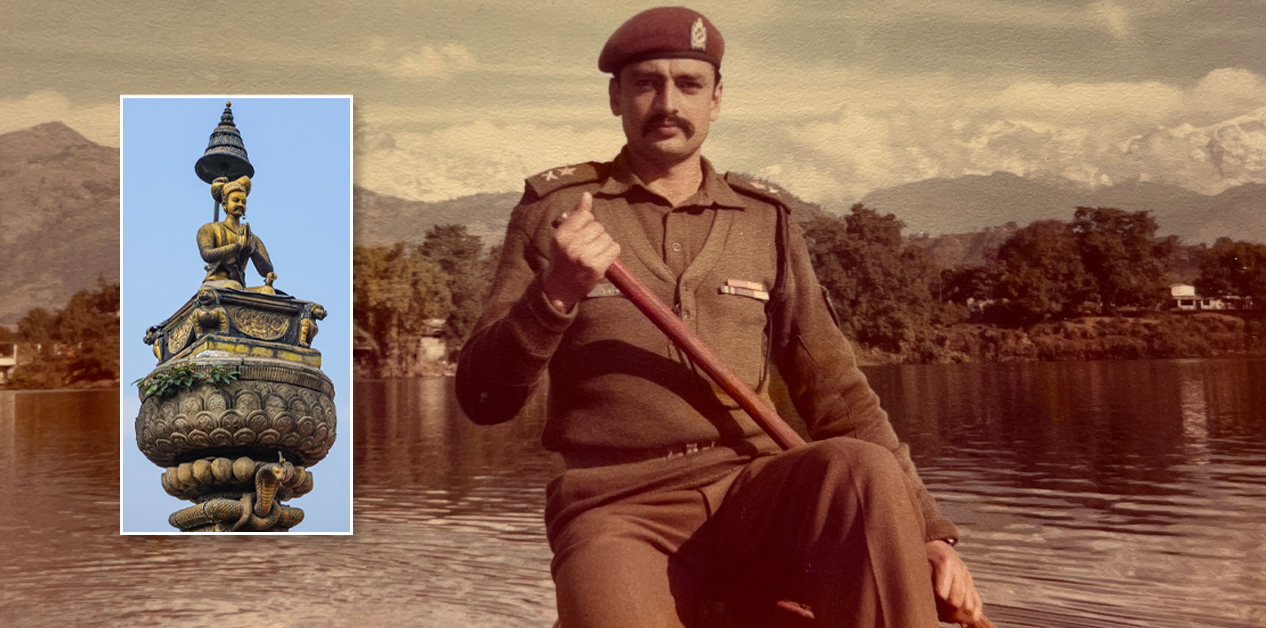

What was the alleged theft of King Bhupatindra Malla’s statue in Bhaktapur Durbar Square? And why did rumors suddenly spread that DSP Rupak Raj Sharma had been killed?

KATHMANDU: On 16 March 1985, Nepal held a much stronger opponent, Malaysia, to a goalless draw on home ground. Jubilant Nepali supporters at Dasharath Stadium were still absorbing the result, but their joy quickly turned into shock. Rupak Raj Sharma, who had led the national football team as the captain for nearly a decade, suddenly announced his retirement.

With ten minutes still left in the match, Rupak removed the captain’s armband and handed it to Suresh Panthi, signaling the end of an era in Nepali football.

Immediately after the match, Rupak was surrounded by journalists, who were stunned by the unexpected retirement decision of one of Nepal’s most popular football captains.

However, Rupak offered a brief response: “I am stepping away from football because I need to focus more seriously on my police duties.”

At the time of his retirement, he was serving as a Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) in the Nepal Police. Soon after announcing his retirement, Rupak flew to the United Kingdom. That is when the rumor mill went into overdrive.

Some newspapers went as far as publishing sensational claims: that the Panchayat regime had killed Rupak; that an underground gang had murdered him and disposed of his body. His name was dragged into an unverified idol theft scandal in Bhaktapur. Wildly speculative news reports and commentary followed.

Unconfirmed reports of his death shook the country. Exaggerated stories flooded the media to such an extent that, for the first time, his family members were forced to step forward and issue clarifications through newspapers.

Even today, the memories bring emotion to Rupak’s 89-year-old elder sister, Indira Sapkota. At the time, she was in New Delhi, India, accompanying her husband, Baturaj Sapkota, who was undergoing treatment at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). While her husband passed away in Delhi, Nepal was gripped by rumors that her brother had been killed. “We were completely stunned,” she recalls.

Rupak’s elder brother Deep Kumar Upadhyay who was a Panchayat member back then and later a senior leader of the Nepali Congress and former tourism minister, was also in Delhi for the treatment of his brother-in-law. As unverified reports of Rupak’s death began appearing one after another in Nepali media, Upadhyay had to rush back to Nepal to issue public appeals. Through various newspapers, he clarified that his brother was alive and had gone to London for a four-month crime investigation training program.

But even that failed to stop the rumors. Instead, new stories emerged: that Rupak had been killed in Britain and that his body would be brought to Kathmandu within a few days.

Frustrated by these reports, Upadhyay publicly released the address and telephone number (924375222) of the Metropolitan Police Academy in Westfield, London, where Rupak was undergoing training. He urged newspaper editors publishing false stories to verify the facts by calling the UK themselves. He also informed the public that Rupak was speaking with family members twice a week. Rupak’s wife, Nita Sharma, likewise stated through the government-owned daily Gorkhapatra that her husband was in good health and safe.

Yet even then, some newspapers claimed that the voice heard on the telephone was not Rupak’s, but someone else’s.

Until Rupak completed his training and returned to Nepal, numerous unverified reports continued to circulate. Only when he reappeared on the field as a football referee did the rumors of his death finally collapse.

What was the real story behind this episode? Why did rumors of his murder spread through Nepali society like wildfire? Even today, the fog of suspicion surrounding the incident has not fully lifted.

The Bhaktapur connection

The controversy is linked to Rupak’s transfer to Bhaktapur district. At the time, incidents of gold smuggling and idol theft were rampant across Nepal. Just days earlier, Nepal Police had busted a major racket involved in stealing idols from the Tripurasundari and Kali temples in Dolakha, arresting suspects in Kathmandu. As investigations began exposing the involvement of influential figures, weekly newspapers suddenly published stories under the headline “The Bhaktapur Idol Theft Scandal.”

The reports claimed that shortly before the Bisket Jatra of 2042 BS (late 2041 BS), i.e. around 1985, a senior member of the royal family had sent courtiers with a crane to remove the statue of King Bhupatindra Malla from Bhaktapur. When the courtiers attempted to extract the statue, locals reportedly appealed to Rupak Sharma, the district police chief at the time. Due to his intervention, the statue could not be taken away. To prevent the palace from being disgraced and to placate Rupak, he was allegedly “rewarded” with a trip to London for “Interpol training.”

Further confusion arose because Rupak had been transferred back to Kathmandu to play football even before these reports were published. At the time, Nepal’s national football team was preparing to play its first-ever home matches for the 1986 World Cup qualifiers against South Korea and Malaysia.

As team captain, Rupak was transferred to the Police Headquarters around December1984/January 1985 so he could join the training camp. Closed training began from 15 January 1985. Nepal was scheduled to play South Korea on March 2 and Malaysia on March 16 at Dasharath Stadium, followed by away matches in Kuala Lumpur on March 31 and Seoul on April 6.

Nepal lost 2–0 to South Korea on March 2. After the goalless draw against Malaysia on March 16, Rupak retired from football without playing the away matches. Six days later, on March 22, 1985, he flew to London for crime prevention training.

Another police officer, Shyambhakta Thapa, also went to London for the same training. However, his name never appeared in newspapers. Only Rupak’s travel was sensationalized. In reality, both officers’ names had been forwarded earlier, and their UK trip was initially scheduled for July-August. When the training schedule changed, they had to depart right after the third week of March. This was also why Rupak retired midway through the World Cup qualifiers.

Former Inspector General of Police Achyut Krishna Kharel dismisses the story outright. “This is simply impossible. Nepal isn’t called a land of rumors for nothing,” he says.

At the time the idol theft story was published, Kharel was an investigation officer at the Police Training Centre. “Do you think anyone could take a crane into the densely populated Bhaktapur Durbar Square to remove a statue without making a huge noise?” he asks. “It’s a matter of deep religious sentiment for the people of Bhaktapur. Would the locals not rise up and retaliate?”

Kharel, who had played a key role in recruiting Rupak into the police as an inspector in 1975, raises further questions. “If there really was an attempt to steal the statue and villagers chased the culprits away, shouldn’t there be at least one police complaint? Where is it? I’ve never seen one. Even during the Panchayat era, people were afraid to speak, but today, shouldn’t the truth have surfaced by now? Is it possible that not a single complaint was filed over such an incident?”

Bhaktapur and Kirtipur were seen as strongholds of communist influence in the Kathmandu Valley. Moreover, during the Panchayat era, influential communist leader Narayan Man Bijukchhe ‘Rohit’ was underground in Bhaktapur.

“If the incident had any basis in truth, what would have happened by now?” asks another former police officer, Rabiraj Thapa.

Thapa, who joined the police service in 1976, adds, “In a place where people once stabbed their own leader, Karnaprasad Hyoju, to death with umbrellas for joining the Panchayat, what do you think would have happened to someone who arrived with a crane to uproot a statue? All these rumors were spread to malign the palace.”

At the time, Bharat Gurung’s name was notorious in idol and gold smuggling circles, and Gurung was known to be close to then Prince Dhirendra. With idol thefts increasing across the country, the Bhaktapur story was allegedly floated by linking it to Gurung.

According to Thapa, as political parties were forming a united front against the Panchayat system in 1985, some newspapers found fertile ground to discredit the royal palace. “Rumors were even spread linking Prince Dhirendra and former King Gyanendra. All of this was nonsense. However, the palace did suffer reputational damage because of Bharat Gurung,” he says.

As idol thefts increased in Nepal, demand in the United States was high, with Tibetans reportedly more active in such crimes. “They claimed the theft attempt happened between 11 pm and midnight, that the city erupted in chaos and the thieves fled. No one was caught. No one knows the exact date. Is that how a real incident works?” Thapa asks.

Although newspapers claimed the attempt occurred in late 2041 BS (mid-March to mid-April 1985), the reports only began appearing around May. Sharad Chandra Shah, then member-secretary of the National Sports Council, strongly objected to these reports. In the 2064 BS (2007) commemorative volume Rupak, he wrote that the claim that Rupak was killed after confronting high-level figures attempting idol theft was entirely fabricated and deliberately planted. Rupak returned from the UK and refereed football matches at Dasharath Stadium, in full public view. Yet none of those who spread the rumors ever admitted their mistake.

Rupak himself never spoke openly about the episode. After he died at the young age of 38 in the Pakistan International Airways plane crash in Bhattedanda, Lalitpur 28 September 1992, the truth behind the incident was buried even deeper in mystery.