Reporting the story compelled me to leave my family and city, as Harka Raj Sampang Rai (Harka Sampang) and his supporters claimed victory — but the truth can be delayed, never defeated.

‘Heartfelt condolences, son of a………’

I noticed a series of insulting tributes on social media. Below the posts was my photo.

It had been about two years since the tradition of paying tribute to a living person began in Dharan. Many people before me had received tributes while they were still alive. At first, it didn’t seem strange. However, one after another, insults and even death threats started coming. A message arrived on WhatsApp: “You don’t have much longer to live.”

Immediately after, another message appeared on my mobile: “Do you have family love or not?”

As the incessant threats continued, a wave of worry overtook me — Dharan hadn’t been this anarchic before!

In fact, Dharan was not like this before. Once a fertile land of art, literature, and theater, it was a city that politically awakened its people. Here, Raamesh and Manjul composed revolutionary songs like “Gaun Gaun Bata Utha, Basti Basti Bata Utha.” Poets such as Bam Dewan and Govinda Bikal traveled to places like Chhintang in Dhankuta to inspire the people toward revolution. Dharan also produced singers like Deep Shrestha and theater and film artists like Nabin Subba, embodying rebellion through art.

Yet, a city that once thrived on dissent and creativity has become “anarchic”—a “city of abusers.”

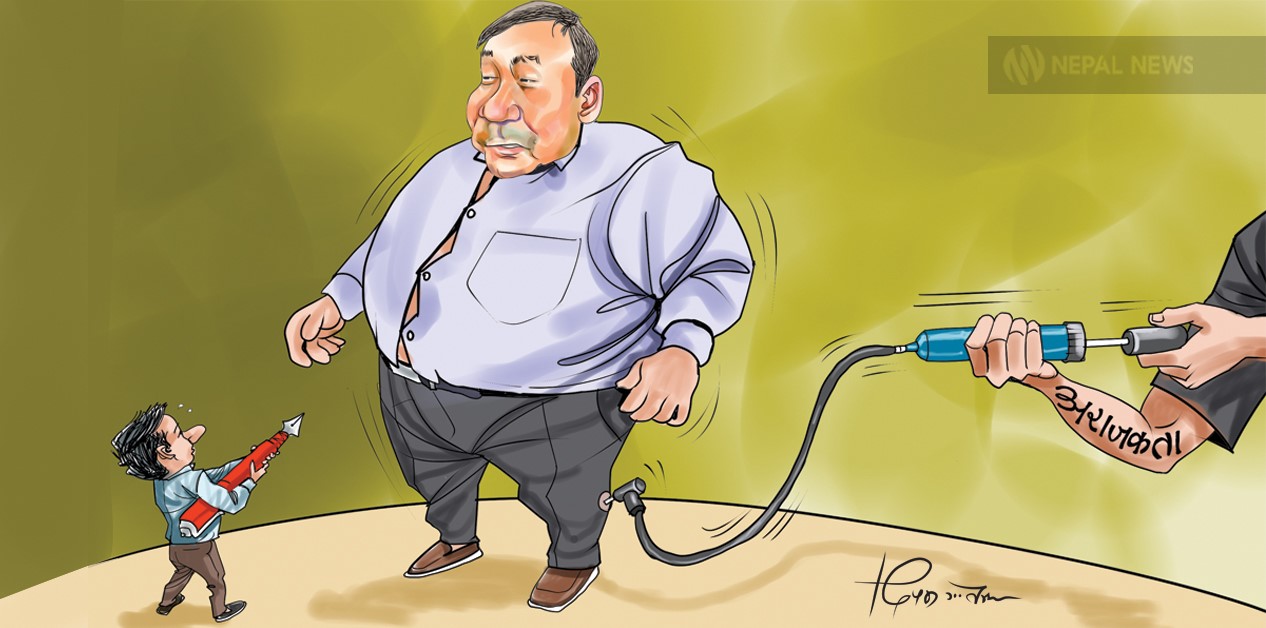

Today, Dharan is under the rule of “Harkaraj”—Mayor Harka Sampang (Harkaraj Rai). He shows no respect for the courts or constitutional authorities, openly declaring, “I do not accept the law as it is.” Political parties and journalists have become tools for his influence.

Journalists and YouTubers who act as Harka’s propagandists label others as ‘Jhole,’ while some are called ‘Khole.’ Sampang, who once went viral for calling elected representatives and party employees “corrupt,” became mayor almost by chance.

As an activist, he advocated for law and order, but after taking office, he has run an arbitrary government, rejecting existing laws and making his own.

His actions—ignoring executive meeting decisions, making unilateral choices, flouting policies and rules, belittling the Dalit community via social media, and occasionally provoking religious tensions—have steadily intensified, leaving Dharan far from the city it once was.

At first, I thought it simply takes time for someone who wins independently to understand the “system.” However, whether it was the Kokah drinking water campaign, the initiative to build the Paruhang statue in Sumnima, or the riverside parks constructed under his leadership, a closer look revealed that neither executive decisions were considered nor existing laws followed.

Whenever someone raised questions, Sampang himself began abusing them on social media. Soon after, his supporters wrote, spoke, threatened, and even paid tribute to him. Political parties and civil society dared not challenge his wrongdoings.

I thought—could this be what people mean when they say, “even God fears fools”?

Mayor Sampang insulted everyone from police DSPs, SPs, and SSPs to the CDO, and repeatedly wrote letters to the Home Minister demanding action against them for not following his instructions. Only a few journalists dared to report on his anarchy, and those who did were insulted by Sampang and his supporters, often labeled “Jhole.”

Harka’s outbursts and insults became a source of income for YouTubers eager to boost views and earn dollars. Older, mainstream journalists hesitated to write or speak openly, fearing controversy. Many had already fallen in line with Sampang’s agenda. Journalists and YouTubers acting as his propagandists began calling others “Jhole” in Harka’s style, while some were labeled “Khole.”

On one hand, Sampang was collecting donations from home and abroad to address the drinking water shortage. On the other hand, he would talk about generating hydropower by turning a dynamo in the rainwater of the Sardu River to light a single small bulb. Whether people believed such rumors or were simply greedy for YouTube views, even journalist friends who understood the basics of journalism were writing about it and making videos—reporting gossip with zero critical sense.

I noticed two types of people following Harka. One group cheered for their own benefit despite knowing the truth, while the other, unaware of his reality, became emotionally swept up by his online hype. Those living abroad, in particular, were sending hard-earned money for Dharan’s development, thinking Harka was honest and blameless. But this money was not being spent according to the law. Harka was not what they imagined; members of his ‘core team’ were involved in financial and moral disputes.

I had seen Harka sing a song twenty years ago. I also knew of an incident where he pretended to be a Maoist to collect money outside a commercial bank and was attacked by real Maoists. From that time onward, he was controversial—both morally and personally. My journalistic instincts told me that his controversial past and chaotic present needed exposure. I knew I would be criticized, knowing journalism is a challenging profession, but I dared to tell the truth.

The police administration, meanwhile, assured me of my safety and encouraged me to work confidently. Yet, for several days, I could not The Center for Investigative Journalism helped me prepare the report.

After multiple stages of editing, it was published on Himalkhabar.com and later on the Center for Investigative Journalism’s website under the title, “Harka Sampang’s Arbitrary Rule: Dharan in the Swamp of Unrest.”

The story began circulating on social media. Some shared it cautiously, saying, “I didn’t write this; Gopal Dahal did.” Janakrishi Rai, then president of the Federation of Nepali Journalists, Sunsari, openly shared the news and even made a video exposing Harka for raising donations by pretending to be a Maoist, since he was familiar with the incident.

Four days after publication, Harka posted three consecutive messages on Facebook regarding my report. In these posts, he ordered me to appear at 10 a.m. the next day, threatening to end my investigative journalism if I failed to comply. Rai, who had posted the video based on my report, was also summoned.

The following day, Harka gathered supporters and YouTubers at a tea shop and publicly threatened to end my journalism. He called me a “thief, arsonist, and donkey,” making it impossible for me to live in the country. He questioned our financial sources, asking, “How are their lives? What money do they eat rice with?”

When some suggested seeking legal recourse if he was dissatisfied with the story, he scoffed, saying, “I do not accept such laws; I will make the laws myself.”

A YouTuber broadcast Harka’s threats live, and Sampang himself posted videos of his abuse on Facebook, TikTok, and other platforms. He incited his supporters to prevent anyone who opposed him from raising their heads. Following this, my Messenger, WhatsApp, YouTube, and Facebook accounts were flooded with threats and abuse. Some offered rewards for cutting off the fingers of the person writing the news, others threatened my life, warning I had little time left, and some even threatened my family, asking where they lived.

Harka Sampang kept writing on Facebook, “Don’t spare my opponent, don’t let him walk with his head held high.” Meanwhile, threats from his supporters kept escalating. Strangers began appearing near my home. I even overheard a group of four or five people on motorcycles pointing at the house, saying, “Gopal Dahal lives here.”

It became clear that Sampang not only sent supporters to verbally abuse but also to physically attack opponents. This was evident when journalist Sanjita Dhamala was assaulted by his people while waiting in line for treatment at the hospital. As Sampang’s supporters loitered near my home, I felt a chill of fear, and my children became afraid to go to school.

Although the police administration assured me of my safety and encouraged me to work confidently, for several days I couldn’t leave the house and couldn’t even check social media. I kept receiving calls from well-wishers, which reassured me that understanding people and the intellectual community were standing with me. I realized that this is the reality journalists often face.

In response, the Federation of Journalists, various organizations, and local political parties issued statements condemning the mayor’s threats. Media coverage of the incident began to grow, drawing the attention of freedom of expression and human rights organizations. Under the leadership of the Federation of Journalists, we filed a formal complaint with the Area Police Office. Subsequently, the Federation’s central committee formed an investigation committee to proceed with a formal inquiry.

However, the police administration did not even summon or question the threatening mayor, Sampang, or his supporters. Instead, they informed us that, since this was a cyber case, the complaint would be forwarded to Kathmandu. The Federation of Nepali Journalists submitted a memorandum to everyone—from the district administration to the Home Minister. The assurances sounded promising, but in reality, they did not translate into action. We were left in shock.

The ‘injustice’ committed by the government

After the administration failed to intervene, the abuse by Sampang’s lawless supporters intensified. After receiving continuous threats and harassment for a month, it became increasingly difficult to continue journalism in Dharan. At that time, the Center for Investigative Journalism arranged for me to temporarily stay in Kathmandu for my safety.

Meanwhile, the investigation team of the Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ) submitted a report to Home Minister Ramesh Lekhak. The report was based on interviews with me, my family, other journalists, political parties, and the police administration.

It recommended that Sampang and his supporters, who were issuing threats, be brought under the ambit of legal action in response to the reporting. The Home Minister promised to take action—this was the second time he gave such assurances. For a while, I felt hopeful, believing that some measure would finally be taken. But that hope, too, eventually turned into disappointment.

After a few months, I returned to Dharan. However, I found the atmosphere unchanged. Once again, a series of indiscriminate posts and insults appeared on social media under the name of the ‘Harka Sampang Supporters’ group, adding my photo and those of other journalists. I filed a complaint with the police cyber bureau, but when I submitted the report to the Home Minister, I lost all faith in the administration’s ability to provide security, which seemed incapable of taking any action.

After that, I felt even more insecure. I began to feel uncomfortable working, and reluctantly decided once again to leave Dharan for a while.

Through these events, I have painfully realized how difficult it is to obtain justice in Nepal. If our police, administration, and state cannot take action against someone threatening a seasoned journalist like me—someone with access to DSPs, CDOs, and membership in an active organization such as the Federation of Nepali Journalists—simply for writing a news story, what kind of justice can ordinary citizens expect, who lack such access?

The police administration, which can track down and even arrest the Prime Minister and other high-ranking leaders from abroad for social media insults, is certainly not weak. Yet, it has become accustomed to addressing only the grievances of the powerful and influential.

I believe that the reason ordinary citizens have lost trust in the government, why young people feel compelled to flee abroad without hope for the future, and why despair is widespread, stems from such unequal behavior by state institutions. But who will listen? At this moment, I am left disappointed, reflecting that we must continue journalism in our own country, expose societal distortions, and instill hope in the next generation—yet, from whom? From the so-called independent mayor, Harka Sampang, hailed as a new face and beacon of hope in politics.

I am currently away from my working base in Dharan, but not away from my duty as a journalist. Sampang and his supporters may feel triumphant for forcing me to leave my family and Dharan over the news I reported. However, they should understand this: Harka Sampang may have won the election, but he has lost in democracy.

Friends, I am not discouraged—I have grown stronger. As the saying goes, “The truth may be delayed or challenged for a while, but it can never be defeated.”

(Gopal Dahal is a senior correspondent at Nepal News, specializing in investigative stories. His case was cited in the U.S. Department of State’s 2024 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Nepal, under the “Physical Attacks, Imprisonment, and Pressure” section.)