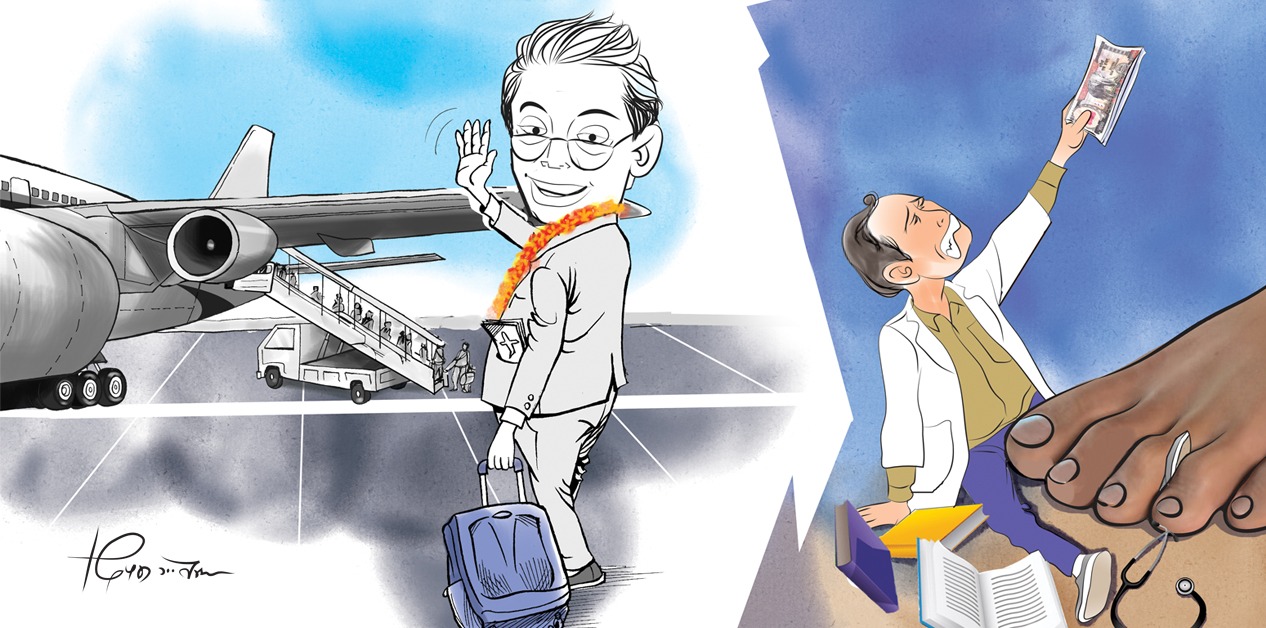

A nationwide shortfall of 6,000 specialists threatens patient care, prompting calls to bring in qualified experts from overseas

KATHMANDU: Dr. Lok Kathayat, a 35-year-old currently serving as a specialist surgeon in the General Surgery Department of James Paget University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK, hails from a middle-class Nepali background. Driven by his ambition to become a doctor, he commenced his MBBS studies at China’s Dalian University in 2010.

Studying MBBS in Nepal used to cost Rs 3.5 million to Rs 4 million, and 40 percent of that had to be paid immediately upon enrollment. There was also an obligation to pay the entire fee within one year. His family did not have the means to arrange such a large sum at once. Therefore, he went to China due to the facility of paying the fees in installments annually. He returned to Nepal after completing six years of study and internship. The six years of study cost Rs 3 million.

After returning to Nepal, he passed the Medical Council exam and completed a further six months of internship. Following this, Kathayat worked as a medical officer in the surgery department of Patan Hospital for two years. The drive to become a specialist led him to Nepal Medical College, where he completed his MS (specialization) in ‘General Surgery.’ Achieving the three years of specialization cost Rs 2.2 million. By the time he completed his studies from MBBS to MS, Dr. Kathayat’s total investment was around Rs 8 million.

When Dr. Kathayat started working as a specialist doctor, he became frustrated. With a monthly earning of Rs 40,000 to Rs 60,000 as a specialist doctor, forgetting about paying the interest on the Rs 8 million investment, it became difficult to sustain his family and manage basic living expenses in an expensive city like Kathmandu. General Surgeon Dr. Kathayat says, “In what state of mind can doctors, pressured by the need to support a family and repay study debts, treat patients? There is neither job security nor certainty about the future.”

Amidst this struggle, Dr. Kathayat passed the Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of the United Kingdom (MRCS) examination.

“It’s been one year since I came to the UK after finishing my studies and started working, and the earnings here allowed me to pay off the loan in Nepal,” Kathayat says. “If I had stayed in Nepal, it would have taken me a lifetime to repay that loan. The working time here is fixed; if you work more hours, you get extra benefits. Most importantly, you feel stress-free when you return home after working here.”

Dr. Lok Kathayat

The story of General Surgeon Dr. Gokul Bhatta of Gorkha is also not different from Dr. Kathayat’s. After obtaining his MBBS from Kathmandu University and MS in General Surgery from Dhulikhel Hospital, he did try to serve in the country’s remote areas.

To sharpen his skills after becoming a specialist, he went to Rapti Academy of Health Sciences, Dang. However, the disorganized management of the hospital and a salary of just Rs 80,000 per month could not keep him there for even three months. After that, he went to Karnali Academy of Health Sciences in Jumla. The salary there was Rs 200,000, which is considered attractive in the Nepali context. However, due to the geographical remoteness and the cost of traveling to and from Kathmandu, that earning was not enough either.

“I managed to work for about one year, but I did not see a secure future,” says General Surgeon Dr. Bhatta. Seeing that it would take twenty years to repay the loan of over Rs 6 million incurred while studying and working in Nepal, he also headed to the UK. He is currently studying and working under a fellowship in the UK. “There are no permanent positions in government hospitals in Nepal; working in private hospitals leads to exploitation. Economic problems and insecurity make it difficult to focus on patient care,” he says. “However, abroad, there is an attractive salary according to your education and skill, and you can work with peace of mind.”

The stories of these two doctors show how specialist doctors who studied with difficulty in Nepal are migrating abroad.

General Surgeon Dr. Gokul Bhatta

According to the Nepal Medical Council, a total of 39,486 doctors are registered across the country from the fiscal year 2017/18 to 2024/25. However, the crowd of young doctors carrying ‘Good Standing Certificates’ in the departure lounge of Tribhuvan International Airport signals how insecure the future of Nepal’s healthcare is. No Nepali doctor can go abroad for study or work without this certificate issued by the Council. The number of people who took permission to leave the country in the fiscal year 2019/20 was at least 1,087, and by 2025, this number had reached 2,681.

According to Dr. Satish Kumar Deo, Registrar of the Council, more than 70 percent of the doctors who take the certificate go abroad permanently. The main reasons for the exodus of Nepali doctors are economic insecurity, low salary, and lack of a suitable working environment.

Specialist doctors are ready to leave the country because the earnings for specialist doctors in other countries are more attractive than in Nepal. Besides Western countries, the number of doctors leaving Nepal for employment in the Maldives and the UAE is also increasing.

According to Council Registrar Dr. Deo, the salary in the Maldives is a minimum of six to seven times and in Qatar eight to ten times higher than in Nepal. This difference reaches up to 30 times in the US and Australia. “Doctors have a high preference for countries like the UK, US, Maldives, Australia, and the UAE,” he says. “It is difficult to retain skilled doctors until the government provides attractive opportunities and a high standard of living.”

According to Dr. Aarti Thapa, president of the Nepali Doctors’ Association UK, at least 1,500 associated doctors are providing services in the UK. The increasing uncertainty caused by political instability in Nepal has accelerated the exodus of Nepali specialist doctors.

General Surgeon Dr. Lok Kathayat and Senior General Surgeon Dr. Kamal Aryal with the surgical team at James Paget University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK, prior to performing robotic surgery.

Looking at the number of 11,990 specialist doctors registered with the Nepal Medical Council, it is not bad. However, a large proportion of this group has migrated abroad. Although the number of specialists in general medicine, surgery, and gynecology looks good, the number of doctors in highly specialized and life-saving fields is low.

Let’s look at an example: Only one person is registered as an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) specialist nationwide. Complex ICU and ventilator services across the country are almost without specialists.

Similarly, there is only one person specializing in treating infectious diseases like dengue and malaria. There are only eight people for the treatment of elderly citizens, whose numbers are increasing in the country. There is only one person specializing in complex abdominal surgery (surgical gastroenterology). There are only 39 people specializing in the treatment of cancer in children nationwide.

The direct impact of this brain drain is sure to be seen in the treatment of complex and specialized diseases within the next few years. Neurosurgery is one such example. A total of 142 people have been trained as neurosurgeons across the country so far. This number is quite promising for Nepal. However, the number of doctors serving in government hospitals among them is limited to six people. The remaining doctors are confined to private hospitals or have migrated abroad.

Dr. Rajiv Jha, Head of the Neurosurgery Department at Bir Hospital, says, “The state has not been able to utilize even 80 percent of the surgeons’ capacity. Due to the lack of equipment and infrastructure, skilled personnel are forced to sit idle.”

According to Dr. Jha, treatment for stroke (cerebral infarction) patients must begin within four hours to save their lives. However, due to the lack of skilled manpower and equipment, not even one percent of patients in Nepal receive timely treatment. “Given the patient-to-neurosurgeon ratio is extremely low, there is a situation where people have to wait for their turn, treatment is delayed, and many patients lose their lives,” he says.

11,990 specialist doctors registered with the Nepal Medical Council, it is not bad. However, a large proportion of this group has migrated abroad.

Nepal requires at least 500 people specializing in neurosurgery to provide treatment services proportionate to the country’s population, but even the available 142 people cannot be retained.

According to Dr. Gopal Sedhain, Head of the Neurosurgery Department at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, doctors are not leaving out of desire but are compelled to go abroad due to the lack of an environment to use their skills. “The government sends doctors who studied on scholarships to remote areas, but there are no CT scans, ventilators, or ICUs there. We are professionals who must work while studying and learning. When sent to places without equipment, doctors cannot use even 10 percent of what they have learned.”

The Nepal Health Workforce Projection 2022–2031 report by the Nepal Medical Commission shows a shortage of specialists. According to the Commission, while Nepal currently requires 14,070 specialist doctors, only 8,291 are available. There is an immediate shortage of 5,779 specialists.

Nepal Medical Council Building. Photo Courtesy: Council’s Facebook

Dr. Satish Kumar Deo, Registrar of the Medical Council, says, “If the government does not take this shortage of specialist doctors seriously in time, it is certain that the unfortunate situation of having to ‘import’ doctors from abroad to treat Nepali citizens will arise within the next decade.” The only way to stop this brain drain is to expand job security, salary, and facilities for doctors and provide services with equipment in remote areas.

The rate of brain drain has increased even more after the Covid pandemic. The rising graph of specialist doctors leaving for abroad suggests that doctors have no patience left to stay in Nepal.

According to Senior Cardiac Specialist Dr. Chandra Mani Adhikari of Shahid Gangalal National Heart Center, the confusion and social frustration seen after the Gen Z protest will certainly increase the number of specialists going abroad.

Nepal requires at least 500 people specializing in neurosurgery to provide treatment services proportionate to the country’s population, but even the available 142 people cannot be retained.

Aspiring doctors also eyeing overseas opportunities

Not only senior doctors but also medical students are migrating abroad after getting better opportunities than in Nepal. However, it takes six years for one student to complete MBBS and at least 12 years to complete Doctor of Medicine (MD). When doctors who have spent a long time studying and invested a lot of money go abroad, it is not only a loss to the country but also to society. Those who study on government scholarships must work in a government hospital in a remote area for two years after MBBS. However, after that two-year contract period expires, they become unemployed.

Dr. Sedhain says, “Even if the government cannot offer employment, merely providing concessions for post-MBBS studies would help many doctors stay within the country.”

Every year, those who have completed MBBS and postgraduate studies are focused on how to go abroad. Once they go abroad, the possibility of them returning is extremely low. Dr. Sedhain asks, “If general surgeons are produced, where will they go? Private hospitals offer minimal salary, and no permanent positions are announced in government sectors.”

Dr. Dipendra Thapa, a neurosurgeon at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, adds, “One reason for higher doctor salaries in other countries is to keep them stress-free and allow them to focus on patient care. But in Nepal, it’s the opposite.” He believes that the government’s perspective of treating doctors and civil servants at the same level discourages specialists. Despite spending 15 to 20 years studying, many doctors are forced to choose private clinics, business, or foreign countries due to a lack of salary, opportunities, and respect.

Shortage in government service

According to Dr. Prakash Budhathoki, spokesperson for the Ministry of Health and Population, doctors are not staying because the permanent position structure is static. Permanent positions have not increased because the government changes frequently, long-term plans are not made, and decisions are stalled, citing ‘financial burden.’

Ministry of Health Spokesperson Dr. Prakash Budhathoki

“Nepal has a population of 30 million; at least 100,000 doctors are required to treat this population,” Dr. Budhathoki says. “But there are not even 2,200 specialists currently in government service.”

Nepal’s health system is running on a ‘permanent position structure’ that is more than 25 years old. There has been no major change to the permanent position structure created in the 1990s, except for minor modifications. The last time 100 people were appointed to government hospitals was in the fiscal year 2017/18. Since then, no advertisements for doctors have been opened through the Public Service Commission.

Although the Ministry has repeatedly put forward proposals to add 12,500 new permanent positions, the files get stuck in the Council of Ministers and the Ministry of Finance, citing increased ‘financial burden.’ Dr. Budhathoki states that specialist positions in central hospitals are completely vacant.

The WHO Health Workforce Support and Safeguards List 2023 report states that due to the shortage of health workers in Nepal, the goal of achieving health targets by the fiscal year 2030/31 cannot be met. The WHO has mentioned in various reports that Nepal, which is on the list of countries with a severe shortage of human resources, will not be able to achieve its health targets.

“Nepal has a population of 30 million; at least 100,000 doctors are required to treat this population,” Dr. Budhathoki says. “But there are not even 2,200 specialists currently in government service.”

According to WHO standards, at least 49 skilled health workers (doctors, nurses, and midwives) are required per 10,000 population, but Nepal only has 22.09 percent of the permanent positions based on the WHO standards. Although the provincial and local levels have added some positions after the implementation of federalism, health services under the federal government are still operating on the structure established 32 years ago. Proportionate to the current population, more than 143,000 permanent positions for health workers are needed. However, the approved permanent positions across all levels nationwide for 32 years are only 31,592. Although the province added some positions after the implementation of federalism, no new positions have been opened under the federal government since the fiscal year 1991/92.

How to stop the brain drain?

If the country’s specialist doctors continue to migrate abroad, there is the challenge of having to bring in foreign specialists to treat Nepali citizens. Senior Cardiac Specialist Dr. Chandra Mani Adhikari of the Shahid Gangalal National Heart Center says that if the government does not create an environment for doctors to stay within the country, a situation may arise where foreign doctors will have to be imported for treatment in the future.

According to Adhikari, the high salary, standard of living, and safe working environment abroad have further accelerated the trend of going abroad. He says, “In the near future, there may be no surgeons to perform complex heart, liver, lung, and neuro-related surgeries. Specialist doctors may have to be imported at a high cost from abroad.”

According to Dr. Gopal Sedhain, Head of the Neurosurgery Department at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, enrollment for specialization studies in heart surgery, kidney, liver, and neurosurgery has stopped for several years in the entrance examinations for Doctorate of Medicine (DM) and Master of Chirurgiae (MCh), which are considered Super Specialist Research Degrees. The number of doctors studying ‘super specialist’ degrees in heart, kidney, and liver surgery has been very low for several years. However, students are attracted to studies in ophthalmology, dermatology, and dentistry. Dr. Sedhain suggests this increased attraction is due to the shorter duration of study and lower risk.

The high salary, standard of living, and safe working environment abroad have further accelerated the trend of going abroad.

Prof. Dr. Anjani Kumar Jha, Vice Chairman of the Medical Education Commission, says that strict regulations alone will not stop the exodus of doctors. “It must be considered natural for doctors, who have spent the most productive time of their lives and a large amount of money studying, to seek better opportunities when they cannot find employment,” he says. The only solution is for the government to immediately create new permanent positions in government hospitals based on the population and patient load and fill those positions.

Respecting the skill, efficiency, and investment of doctors, an attractive salary and benefits package must be provided. Before sending doctors to remote areas, there must be equipment like CT scans, MRIs, and ICUs where their skills can be utilized. The government must ensure complete safety in the workplace. He says that doctors will only stay if there is a clear career path and opportunities for professional growth in government service after completing MBBS and postgraduate (specialization).

According to Senior Cardiac Specialist Dr. Chandra Mani Poudel of the Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Center, if the government does not introduce policies and programs to stop the doctor brain drain in time, Nepali citizens will either have to go abroad for treatment or wait for foreign doctors in the coming years. He says, “There will be no one to treat the poor patients in the remote areas.”