A huge amount of money leaves the country every year along with Nepalis going to Indian hospitals

KATHMANDU: Ram Maya Ghale, who was the in-charge of endoscopy at Om Hospital in Kathmandu, saw a problem develop in the liver of her husband, Dhan Bahadur Gurung (51), five months ago. She admitted her husband to the very hospital where she worked on 23 August 2025 and had him treated for three months. But instead of improving, his condition kept worsening.

Water accumulated throughout Dhan Bahadur’s body, and his weight doubled. Ram Maya recalls, “Thirty-six liters of fluid had to be drained from his body. We had almost lost all hope.”

When treatment in Nepal no longer seemed possible, Dr Rahul Pathak of Om Hospital suggested taking him to Delhi. By then, 1.6 million rupees had already been spent on treatment in Nepal. Having heard that treatment in India was more effective, Ram Maya took her husband to Max Hospital in New Delhi on 12 November 2025. There, Dhan Bahadur successfully underwent a liver transplant.

Although Rs 7.2 million was spent on her husband’s treatment in Delhi, Ram Maya is happy that he received good care. “Even though it cost so much money, my husband’s life was saved,” she says.

Based on her experience, she believes there are serious quality issues with some medicines sold in Nepal. While in Nepal, the diuretic medicine (Lasix/Furosemide) given to her husband did not work. But in Delhi, when she bought and used a medicine with the same name, it worked immediately. Having spent 23 years in the health service, she says, “In Nepal, not all medicines prescribed by doctors are available, and even those that are available are not of good quality. Instead of recovery, the disease keeps worsening.”

Suresh Dhami of Mahendranagar, Kanchanpur, came to Kathmandu last September for treatment after experiencing difficulty while eating. He was admitted to Kathmandu Medical College (KMC). A biopsy confirmed pancreatic cancer.

Even after staying in the hospital for two months and undergoing surgery, he could not feel reassured. By then, Rs 1.1 million had already been spent. Because he had to wait in long lines for chemotherapy and because of limited equipment and long waiting times, he decided to go to India for further treatment. He went to Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Hospital in Delhi.

Nepali Citizen Suresh Dhami Undergoing Treatment in India

During two months of treatment there, he spent Rs 2.1 million. “Although it cost money, the disease is now at a curable stage, so I am not worried,” he says. He also shares that he goes to India every 15 days for follow-up.

Ram Maya and Suresh are just examples. Every year, thousands of Nepalis travel to cities like Delhi in India for the treatment of cancer and complex diseases related to the liver, heart, neurology, and kidneys. As Nepalis increasingly choose India as their destination in search of reliable treatment, not only are billions of rupees leaving the country each year, but this trend is also exposing the state and character of healthcare services within Nepal.

Why do Nepalis go to India?

Treatment for complex health problems is expensive in itself. On top of that, going to India and staying there for a long time for treatment adds travel, accommodation, food, and medical expenses, resulting in a very large total cost. Yet it is not only the wealthy—middle- and lower-middle-class Nepalis are also increasingly going to hospitals such as Apollo, AIIMS, Medanta, Max, Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Hospital in Delhi, and hospitals in other cities for treatment.

The growing number of people traveling for the diagnosis and treatment of complex diseases shows that India is becoming an attractive destination for Nepalis. However, hidden within this “attraction” is a sense of compulsion.

Those who go to India for health problems say they do so for accurate diagnosis and quality, reliable treatment. In other words, they cross the border because they are not confident about these aspects in Nepal. This indicates a lack of public trust and confidence in the country’s healthcare system. Even doctors themselves acknowledge that they have not been able to earn patients’ trust.

According to Dr Subash Pandit, a cancer specialist at the Civil Service Hospital in Minbhawan, Kathmandu, there is a deeply rooted perception among Nepalis that cancer cannot be correctly diagnosed or treated in hospitals within the country. “Because of this, even though services and technologies have improved compared to the past, we have not been able to win patients’ trust,” he says.

On the other hand, cancer treatment is long-term and expensive. Many patients go to India from the very beginning, thinking that even if they start treatment in Nepal, they will eventually have to go to India anyway, Dr Pandit explains. After receiving treatment in India, patients also tend to go there for follow-up. “Many patients are not aware that follow-up can be done in Nepal. If follow-up were done in Nepali hospitals, patients could save a large amount of money,” he says.

Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Hospital in India

Some major Indian hospitals have even opened contact offices in Nepal. Agents promote these hospitals and encourage people to seek treatment there, which is another reason for the influx of Nepali patients to Indian hospitals, according to Dr Pandit.

Hospitals such as KIST in Nepal sometimes host doctors from Delhi’s Apollo and Max hospitals to perform liver transplants. However, this has not significantly reduced the number of Nepalis going to Indian hospitals. Ram Maya points to post-surgery follow-up as the reason. She says, “After completing surgery in hospitals here, Indian doctors return to India immediately. If complications arise later, there is confusion about which doctor to consult. When treatment is done in India, there is regular contact with the doctors who performed the surgery, which gives peace of mind.”

The experience of Suresh from Kanchanpur, who visited Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Hospital, illustrates the pressure of Nepali patients in well-known Delhi hospitals. According to him, on average, about five out of every twenty beds in Delhi hospitals are occupied by Nepalis. “When treated in Nepal, there is no confidence that the disease will be cured, so Nepalis go to India even though the treatment is expensive,” he says.

In his experience, for residents of the Far-Western region, New Delhi is closer than Kathmandu, making it easier and cheaper to go across the border for treatment. “From Mahendranagar, you can reach Delhi in six hours by road, but it takes 17 hours to reach Kathmandu,” he says. “A one-way reserved vehicle fare to Delhi is 6,000 rupees, whereas a one-way flight from Dhangadhi to Kathmandu costs 12,000 rupees per person.”

Patients with cancer, heart, neurological, and kidney problems go to India either by choice or on doctors’ recommendations when treatment is not possible in Nepal. The growing trend of Nepalis going to India for cheaper, better, and faster treatment reflects the impact of “medical tourism.” Nepalis from border areas of Madhesh, Sudurpaschim, Karnali, and Lumbini provinces often prefer Indian hospitals.

Hospitals in border cities connected to India—Mahendranagar, Dhangadhi, Nepalgunj, Butwal, Janakpur, and Biratnagar—lack equipment and facilities such as ICUs, ventilators, CT scanners etc. Patients’ relatives say that as soon as critically ill patients arrive, doctors at these hospitals often state that treatment is not possible and refer them to India.

A study published in 2020 by Dr Keshav Basyal and Lalita Kaudinya Basyal identified mistrust in Nepali doctors and hospitals, along with a lack of technology, as the main reasons Nepalis go to India for treatment. The research article titled “Nepali Patient Treatment in India: Motivation and Experience”, published in the journal Shwet Shardul (Volume 17, Issue 1, 2020) of Madan Bhandari Memorial College, notes that the availability of advanced technology and specialist doctors in Indian hospitals is the key factor attracting patients from Nepal.

The study also states that India has become an easy option for treatment because it can be reached conveniently through open borders, buses, trains, and air travel. “Due to Nepal’s weak health system, centralized health facilities, and lack of specialist services, many Nepalis are compelled to go to Indian hospitals,” the study notes.

Similarly, according to a research paper titled “Cancer Care and Research in India: What Does It Mean to Nepal” published in The Lancet Oncology, Nepalis depend on India for cancer treatment. In particular, patients or their collected samples are sent to India for PET scans and “hybridization” tests. Although visual inspection using acetic acid for cervical cancer screening is also available in Nepal, many Nepalis still go to India for this purpose, the study conducted by Bishal Gyawali, Bishesh Sharma Paudel, Tomoya Shimokata, and Yuichi Endo states.

A large number of Nepalis work in various cities across India. Patients from Nepal find it easier to go for treatment with the support of these relatives. According to the Basyals’ study published in Shwet Shardul, relatives working in India help Nepali patients arrange hospitals and accommodation. This has made India an accessible treatment destination even for middle- and lower-middle-class Nepalis.

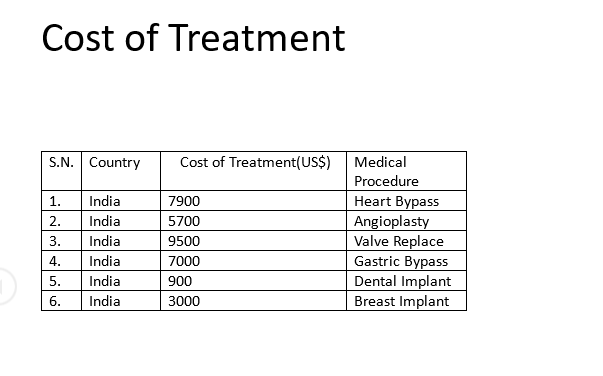

According to the 2020 study, treatment costs in Indian hospitals were as follows: heart bypass surgery—1.486 million rupees; angioplasty—823,000 rupees; heart valve replacement—1.371 million rupees; dental implant—130,000 rupees; and breast implant—433,000 rupees. These costs may have increased or decreased over time.

Dhirendra Sinal, who goes to India for medical treatment, says that treatment there is faster and more effective. “In Nepal, both time and money are spent endlessly on tests, and it becomes very difficult to even diagnose the disease,” he says, sharing his experience. According to him, due to Nepal’s weak health system, lack of technology, and the migration of skilled manpower abroad, thousands of Nepalis end up in Indian hospitals every year.

Although overall treatment in India is expensive, some tests are cheaper there compared to Nepal. For example, a PET scan for cancer costs around 70,000 rupees in Nepal. The same service costs 20,000 Indian rupees (around 32,000 Nepali rupees) in India. According to Dr Pandit, a cancer specialist at the Civil Service Hospital, Nepal has very few PET scan machines and similar equipment needed to diagnose complex diseases like cancer. He explains that the drugs used in these machines expire quickly, which makes the service more expensive in Nepal.

Public health expert Dr Sharad Onta suggests that to end the compulsion for Nepalis to go to India and other countries for treatment and to control the outflow of money, Nepal’s domestic health services must be improved. He says that only by retaining skilled manpower within the country, ensuring the quality of medicines, and making post-surgical care reliable can Nepalis feel confident seeking treatment at home. “If health sector reforms are delayed any further, beds in Nepali hospitals will remain empty,” he warns.

Cancer patients: up to one million rupees spent per month

Because India offers advanced and high-quality healthcare services, patients from many countries go there for treatments such as surgery, bone marrow transplants, joint replacements, and robotic surgeries. According to Nepali doctors, Nepalis go to India for both complex and even common diseases.

Despite the large number of Nepali patients going to India, the government does not have exact data. According to Suman Nepal, information officer at Nepal Rastra Bank, it is difficult to determine the number of patients because people travel to India not only for treatment but also for tourism.

Dr Keshav Basyal, who has studied the practice of Nepalis going to India for medical care, also says that due to the open border with India and the lack of a system to record people’s movement, it is difficult to separate how many people went for treatment and how much they spent.

Kabin Shrestha, the focal person at Max Hospital in Delhi, says that around 600 Nepalis travel daily from Nepal to Delhi alone for treatment.

Most patients going from Nepal to India are cancer patients. The Government of Nepal has arranged travel concessions on the national flag carrier, Nepal Airlines Corporation, for cancer patients going to India for treatment. On the recommendation of cancer survivor societies, the airline provides ticket discounts. According to the corporation, cancer patients receive a free flight in the first phase, a 50 percent discount in the second phase, and a 25 percent discount thereafter.

According to data up to mid-June to mid-October 2025, as many as 393 cancer patients traveled to Delhi for treatment via Nepal Airlines. Based on this number, an average of 98 patients per month travel for treatment. Suresh Dhami, who underwent pancreatic cancer treatment at Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Hospital in Delhi, spent 2.1 million rupees over two months. Using this as a reference, it appears that cancer patients going to India spend around 1.05 million rupees per month. On this basis, assuming that cancer patients stayed for treatment for two months, the estimated expenditure by the 393 patients who traveled by air amounts to approximately 82.53 million rupees in total.

This amount covers only the expenses of cancer patients who traveled using discounted fares on Nepal Airlines Corporation aircraft. If the costs incurred by patients traveling for treatment of other diseases—both in the initial stages and later for post-surgery or post-transplant follow-up—are added, the total amount Nepalis spend on medical treatment in India would be many times higher.

Cancer specialist Dr Pandit remarks that the government policy of providing airfare concessions for patients going to India for treatment, while not offering similar discounts for travel within the country, actually encourages Nepali patients to seek treatment abroad.

According to a survey conducted in 2015–16 by the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics (DGCIS) under India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry, around 11,399 Nepalis used health services in India. Since this data is nearly a decade old, it does not reflect the current number of Nepalis traveling to India for treatment. The survey also did not mention the total expenditure incurred by Nepalis during treatment in India at that time.

A study report titled “Liberalizing Health Services under the SAARC Agreement on Trade in Services: Implications for South Asian Countries”, conducted in 2011 by the South Asia Center for Policy Studies, cites Nepal Rastra Bank data stating that in 2008, USD 18.93 million was spent outside Nepal on healthcare (equivalent to an average of approximately Rs 2.517 billion per year at the current exchange rate). The study notes that this figure is a serious underestimation, as most healthcare transactions in the Nepal–India border areas are not included in official records.

The same study, conducted by a team including Nepali researchers Pushpa Sharma and Chandan Sapkota along with nine researchers from other South Asian countries, cites Indian tourism data stating that out of 87,487 Nepalis who visited India in 2009, about 1,662 went for medical treatment. Of them, 98.9 percent traveled by air and 1.1 percent by land. The study suggests that because of the open border and the lack of official records for land travel, many Nepalis who travel daily by road are not counted, indicating that a significant number may have gone to India for treatment via land routes. The study further states that due to open borders and informal channels, there is no accurate data on either the number of Nepalis going for treatment or the amount they spend.

It is also stated that, compared to other countries, Nepalis do not need prior approval from a medical board to seek treatment in India, which further makes it difficult to calculate exact figures.

Healthcare services: expanded, but not high-quality

Compared to the past, healthcare services in Nepal have expanded. Due to municipal-level hospitals, citizens are now able to access treatment services within their own communities. However, due to the lack of quality and reliable healthcare, people still cannot feel confident throughout the process—from testing and diagnosis to treatment. Government hospitals lack sufficient equipment, healthcare workers, and essential medicines, while treatment costs in private hospitals are often unaffordable. The health insurance program introduced to improve access for poor and marginalized citizens is also deteriorating due to problems and irregularities. The public does not trust the quality of services provided by insurance-affiliated health institutions.

Because of these problems, citizens—frustrated by long delays in diagnosis, the need to wander from facility to facility, and spending hundreds of thousands of rupees just on tests—end up seeking quality treatment elsewhere, even taking loans to travel to neighboring countries.

Gopal Sedai, deputy director of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, argues that government hospitals are forced to handle far more patients than their capacity, which prevents them from delivering quality services. According to him, the necessary technology for all types of treatment is not available, and there is also a shortage of manpower and budget. “When we try to hire doctors on contract, they don’t come. The government does not open permanent positions. In such a situation, what can hospitals do?” he asks.

Dr Pandit, a cancer specialist at Civil Hospital, agrees that Nepalis are still compelled to go to India for certain treatments. According to him, services such as pediatric bone marrow transplants, robotic surgery, and technologies that identify genetic information after biopsy and guide further treatment are not available in Nepal. However, to stop people from traveling to India even for treatments that are possible in Nepal, he says managerial reforms are needed. “Many Nepalis are also cheated when they go to India for treatment. There is no alternative to organizing Nepal’s healthcare system properly to prevent this,” he says.

Dr Prakash Budhathoki, spokesperson for the Ministry of Health and Population, acknowledges that government health services are still operating based on staffing structures from 2040 B.S. (circa the 1980s), and that most hospital equipment also dates back to that period, making efficient and effective service delivery naturally difficult. Healthcare workers are struggling to provide services with decades-old staffing provisions. “We are somehow providing services by hiring some staff on contract. One health worker is doing the work of four or five people. In some cases, they have even administered chemotherapy to patients seated on chairs due to the lack of beds,” he says.

According to Dr Budhathoki, the ministry does not have the budget to add the required manpower in the health sector. Although staffing expansion requires approval from the Ministry of Finance through the Ministry of Federal Affairs, the Ministry of Finance has been tightening spending. “Most of the equipment in government hospitals dates back to the 1980s. Many of them are no longer usable. The budget for equipment management should increase by 10 percent, but the Ministry of Finance increases it by only four to five percent each year,” he explains.

He adds that although much work remains to be done in the health sector, everything remains incomplete, stalled, and disorganized due to lack of budget. “There are plans to build cancer hospitals at the provincial and regional levels. We also need our own laboratories to test all types of medicines. Ironically, we have not even been able to provide training to specialist doctors,” he says.