Local stories need universal depth and strong teamwork to resonate internationally

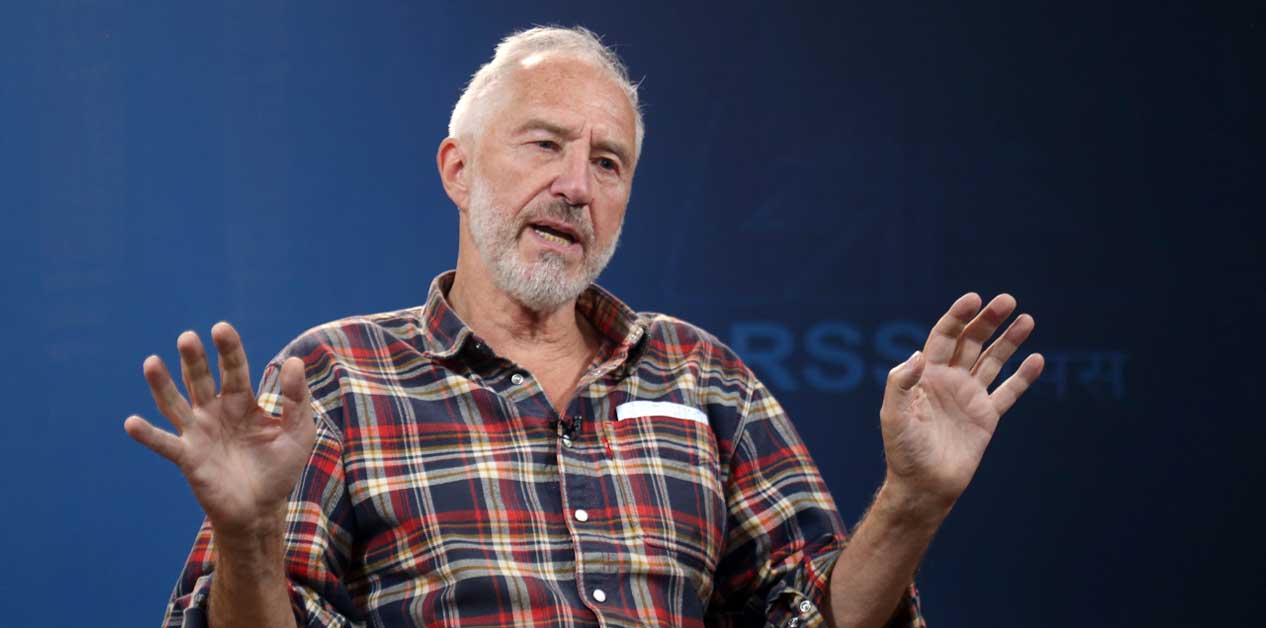

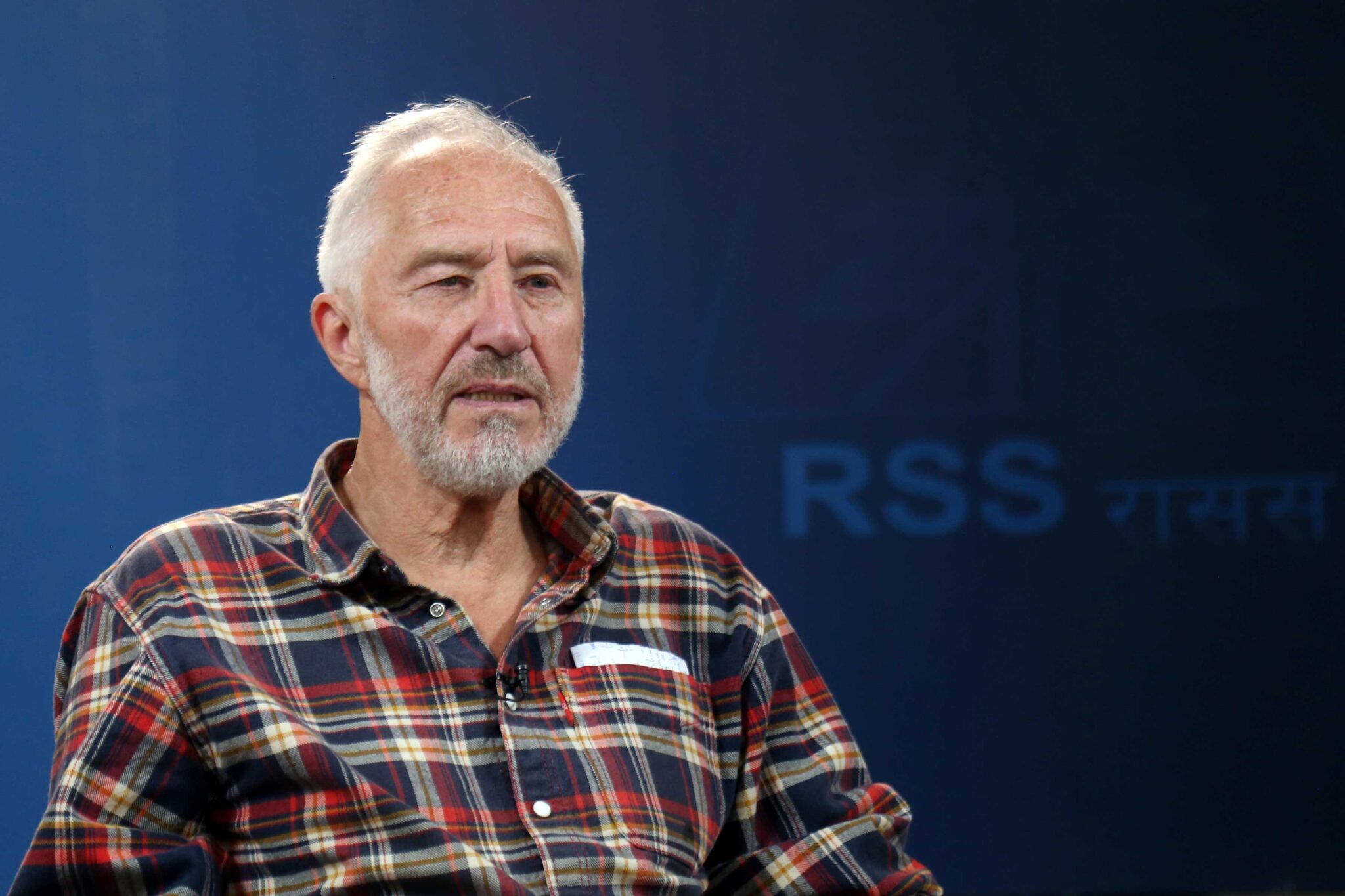

KATHMANDU: The renowned French photographer and film director Éric Valli is famous for his work portraying the lifestyle of Nepal’s Himalayan communities and their relationship with nature. Born in France in 1952, he has worked continuously in Nepal since the 1980s.

Valli profoundly captured the life, cultural beauty, and struggles of Upper Dolpa, producing the film Caravan (Himalaya) in 1999. The film was even nominated for the Academy Awards (Oscar).

He has also directed documentaries, including Honey Hunter, Nepal, Beyond the Clouds, and Himalayan Gold Rush. Valli’s photos are published in National Geographic, Geo Magazine, and other major international publications.

Valli, who considers Nepal his ‘second home,’ has recently developed an interest in the Chhath festival celebrated in the Terai region. Valli sat down with RSS during his recent Nepal visit. Below is an edited excerpt of the conversation:

What keeps you connected to Nepali culture, society, and lifestyle for such a long period of continuous engagement?

Nepal was ‘love at first sight’ for me. In one word, it is love. I first came to Nepal in 1973. I remember coming via India’s Varanasi route. I traveled by trekking and sitting on the roof of a large truck.

The attractive terraced hillsides here, the distinctly shaped red and white plastered houses, and the incredible Himalayan views visible behind those houses made my heart pound faster. The sight of the geography and lifestyle here about 50 years ago made me fall in love with Nepal at first sight.

I am a French citizen. My country is also beautiful. After many years of a tedious life in France, the experience in Nepal became marvelous for me. Even the difficult and unusual paths in Nepal became an interesting experience. After coming to Nepal, the culture here felt like a goldmine of new cultures for me.

How do you recall your experience and engagement with the community and culture of Dolpo, where your film ‘Caravan’ was filmed?

I first reached Dolpa around 1981. Since Dolpa was almost restricted for foreigners, the government initially denied me entry permission as well. But as soon as I arrived in Dolpa, I experienced a ‘culture shock.’ At that time, Dolpo was not accustomed to the outside world. Dolpa’s special culture is also a reason why I love Nepal. I stayed for a long time at the house of my friend Thinle (the main character of Caravan), and I traveled and understood Dolpa with him. I made the film based on his suggestion. He was the one who suggested to me, ‘You are only making a book on Dolpo culture; why not make a movie?’

After that, we began the production of Caravan after deeply studying Thinle’s lifestyle, story, culture, and struggles along with Dolpo. The people of Dolpa lived in houses made of stone and wore clothes they wove themselves. Their lifestyle was difficult, but they were very brave and hardworking.

Nepal is a place where a lot of research can be done. Dolpa was an interesting place to study. While making the film there, I expanded my relationship with the locals not just as a colleague but as a friend. I am still in touch with them.

French photographer and film director Éric Valli. Photo: RSS

Let me share an anecdote. My shoe tore during a journey to Northern Dolpa. I asked a local to make me a new pair of shoes. The conversation I had with him about the size and cost of the shoes made from yak hide still amuses me. He said, ‘I have never made such a large shoe before, but I can make it.’

When I asked for the fee, he said, ‘Give me 40 pathis (traditional Nepali units of measurement for grains and volume) of flour.’

I told him I did not have flour, so I would give him money. He said, ‘Your money can’t do anything for me; give me flour.’

Finally, the shoes were made only after I bought and gave him the flour. That time was different. And I was extremely in love with that old Dolpo. As I remember, the Dolpo at that time was also challenging.

What differences do you observe in Dolpo between 50 years ago and now?

Many things have disappeared in Dolpo 50 years later. Dolpo has changed since the road arrived. Back then, Dolpo, where houses with flat roofs were visible, looked dry. Perhaps due to global climate change, it rains now. The endangered, original, and interesting physical structures and architecture are no longer in use. I also saw the effect of Nepali youth going abroad in Dolpo. Villages are empty. Only the elderly remain.

As a foreign director, how easy or difficult was it for you to responsibly portray Nepali culture in film?

I was a carpenter by profession; film was my hobby. As a foreign director, I worked a bit harder. I am not only honest with my work but also equally honest with the culture and community here. The love for this country and culture helped me make the film. If we are to make a film, we must know about the subject matter. Deep study is necessary even before shooting the film. A good script must be written. I studied for three years just to write the script for Caravan. Deep study increases one’s understanding of the story and characters, and the path opens itself.

I still remember Thilen saying, ‘Our culture is also melting away like snow.’

I replied, ‘My culture is also melting away in France.’

Now, globalization is changing everything even more. Every culture has unique features that must be protected; documentation is necessary. Whether by writing a book or making a film, it must be preserved. While writing the story of Dolpo, that film ended up being the world’s last caravan. It was truly a great responsibility. It involved many challenges and complexities.

What are your suggestions for taking Nepali films directed by Nepali directors to the global community? What should new directors focus on?

While writing the script for Caravan, I was fully conscious of needing to reflect Nepali culture. But I was equally conscious of how to make it global and reach an international audience. I had to extract a ‘universal’ story. If a film only shows culture, it is limited to the audience who understands that culture. The story of Caravan itself is based on a generational conflict between an old man and a youth. That is why the film shows the struggle between two generations for leadership, which is something all audiences worldwide can understand and be attracted to. The production of Caravan was not possible with small effort. Selecting characters from the community itself was also important work.

To take a local story to an international audience, the story must become ‘universal.’ A strong team is also needed. No one might have imagined Caravan would be so successful. I myself did not know it would reach the Oscars. I worked hard, and that hard work took it there.

Honey Hunter was also one of the most popular stories in National Geographic. This is because it was not just a Nepali story but a universal one.

What kind of impact do you think your films have had on the world’s perspective toward Nepal and Nepali culture?

It is my understanding that my films have certainly succeeded in drawing the world’s attention to Nepal. I believe that tourism, cultural interest, and conservation efforts in Nepal have also begun to increase. More promotion is needed to make Nepal a tourist destination. I also worked on promotion to take Nepali culture to the world community. This requires working with those who have international contacts, which is very expensive.

I did not receive possible support from the Government of Nepal for the promotion of my Nepali film production. Caravan reached the Academy Awards. Honey Hunter was covered in National Geographic. But despite this love, goodwill, and good work for this country, I have repeatedly faced problems obtaining visas from the Government of Nepal. Nevertheless, I love the Nepali people. I love Nepal. I am confident that my work will always have a positive impact in favor of Nepal and the Nepali people.

(RSS)