KATHMANDU: As Nepal enters yet another uncertain chapter—an interim government led by Sushila Karki declaring fresh elections after the Gen Z revolt upended the political order—geopolitics looms as both challenge and constraint.

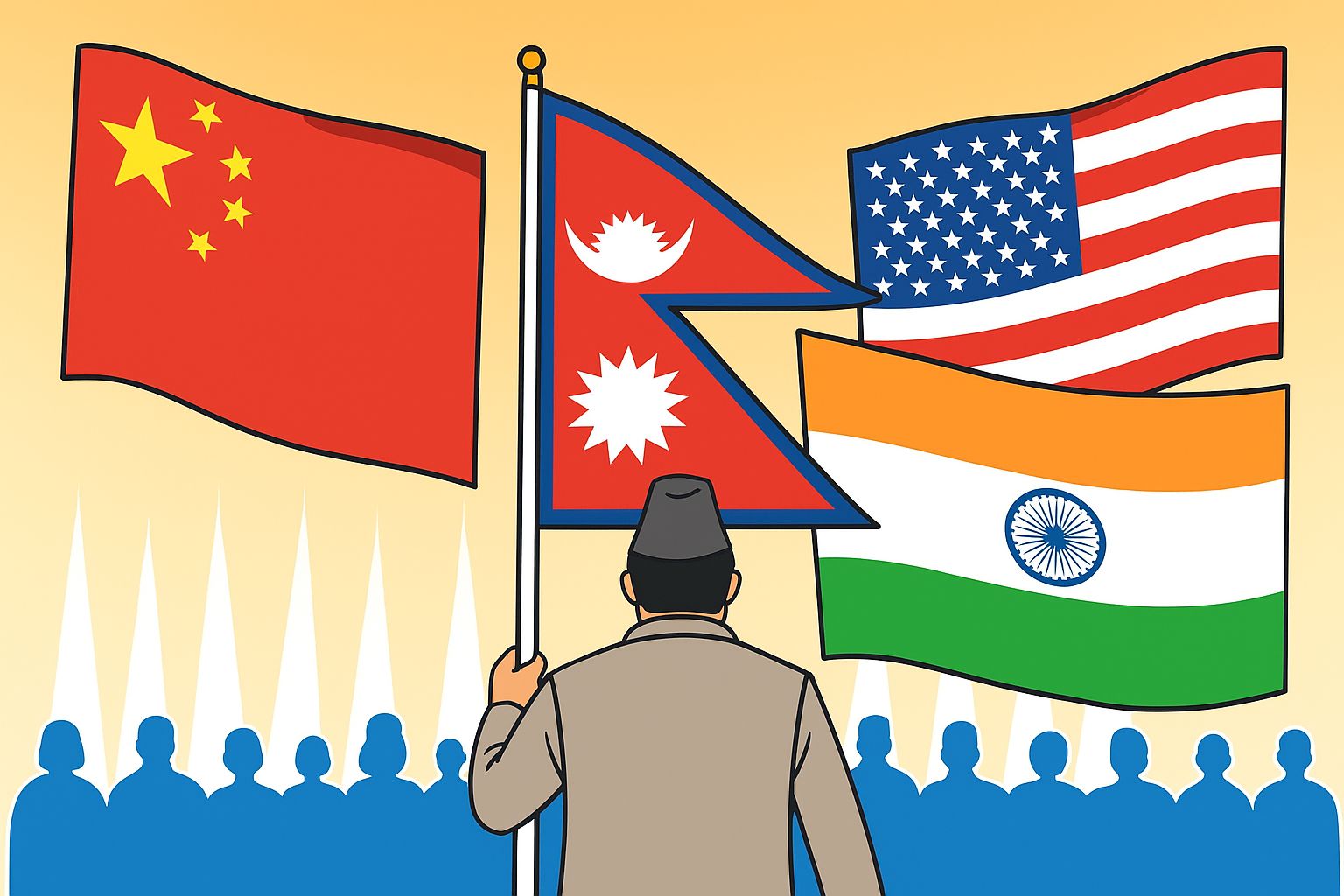

For decades, Nepal’s survival has depended on the art of balance: pragmatically managing the rival ambitions of India and China while struggling to pursue its own economic and political goals.

Today, that balancing act has grown even more fraught. Rumours of foreign hands in the recent youth uprising have only heightened speculation about Nepal as a pawn in a wider strategic game.

Yet the fundamentals remain unchanged: a small, landlocked nation, vulnerable to its geography and dependent on external goodwill, has no option but to engage rigorously with all friendly neighbors—India, China, and increasingly the United States.

The question now is whether Nepal can turn its precarious location into leverage for stability and growth—or remain trapped by it.

Kathmandu in the crossfire

Nepal’s latest political crisis illustrates how domestic turmoil in small states can reverberate far beyond their borders.

Within 30 hours of protests erupting in Kathmandu, the coalition of the Nepali Congress and the UML—commanding nearly two-thirds of parliament—had collapsed.

The uprising was triggered by anger over corruption, nepotism and a brief social-media ban, yet its consequences are being parsed primarily through a geopolitical lens.

For Nepali analysts, few events are free from foreign intrigue. The “Gen Z revolution” is no exception. Rumours swirl that Washington orchestrated the protests, likening them to a colour revolution; others suggest India quietly nudged events to unseat a China-leaning prime minister.

Beijing, for its part, suspects an alignment of rivals. None of these claims is backed by evidence. But in Nepal, gossip and conspiracy carry unusual weight, and the geopolitical context gives such speculation credibility.

That context is stark. Nepal sits between Asia’s two rising giants, India and China, while also figuring in America’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

Each power claims benign intentions; none is viewed as disinterested. China counts Nepal as a Belt-and-Road partner, having inked infrastructure deals and courted Kathmandu as a buffer against Delhi & Washington.

India, which still supplies much of Nepal’s energy and commands its biggest market, regards the Himalayan state as part of its natural sphere of influence.

Washington, meanwhile, has invested half a billion dollars through the Millennium Challenge Corporation compact, officially for development but locally debated as a strategic foothold to counter China.

The fall of K.P. Sharma Oli unsettles this triangular balance. Mr Oli had recently attended a China’s victory day parade, signalling a tilt northwards. His sudden exit was greeted warmly in Washington and New Delhi, which had grown wary of his alignment with Beijing.

For China, the timing could hardly be worse. It had invested heavily in cultivating Nepal as a showcase partner, only to see that effort disrupted by an unexpected youth revolt.

The reality, however, is that Nepal’s convulsions are less about great-power plots than about local discontent. Yet geopolitics ensures they do not remain local.

Infrastructure loans, aid packages and trade concessions are all interpreted as strategic instruments. Domestic politicians, in turn, exploit this environment—seeking foreign patrons as eagerly as they seek voters.

Each protest or policy dispute thus becomes an extension of the broader contest between New Delhi, Beijing and Washington. For India, the upheaval offers relief: a government less inclined to lean towards China.

For America, it underscores the value of patient engagement in a region where small states can matter disproportionately.

For China, it is a reminder that projects and promises do not translate into political stability. The lesson for Nepal is sobering. Its democracy remains fragile; its sovereignty, though intact, is constantly filtered through others’ strategic calculations.

Whether or not foreign powers played any role in the latest uprising, they will all compete to shape what follows. In the Himalayas, even a local youth protest can quickly become part of a global rivalry.

The yam between giant boulders

When Prithvi Narayan Shah, the unifier of Nepal in the 18th century, described his fledgling kingdom as “a yam between two boulders,” he could hardly have imagined how prophetic his metaphor would become.

Nearly 250 years later, Nepal remains wedged between the world’s two most populous countries—India and China—while increasingly drawn into the orbit of a third, the United States.

For a small Himalayan state, this geography is both a blessing and a curse: it guarantees relevance in great power politics but leaves little room for error.

Today, as global geopolitics is reshaped by China’s rise, America’s recalibration, and India’s own quest for status, Nepal finds itself once again at the fault line of competing ambitions.

From the corridors of Kathmandu to the dusty tea shops of the Terai, debates about bhurajniti—the Nepali equivalent of geopolitics—have become ubiquitous. But as arguments rage over aid, alliances, and sovereignty, one question looms above all: can Nepal craft an independent foreign policy in a world of intensifying rivalries, or will it remain a pawn on someone else’s chessboard?

A connected history

The Himalayas have always been a frontier of empires, faiths, and trade. For centuries, Nepal functioned as a civilizational bridge—Hinduism flowing northward, Buddhism southward, commerce east to west.

The British Empire’s 19th-century “Great Game” with Tsarist Russia turned Tibet, Afghanistan, and Nepal into buffers and bargaining chips.

Nepal survived colonial encroachment, but only by concession. The 1816 Sugauli Treaty stripped it of territory, effectively making it a British protectorate.

In exchange, Britain recognized Nepal’s sovereignty in 1923, giving Kathmandu a precarious independence—one acknowledged in principle but often doubted in practice.

Indeed, when Nepal first applied for UN membership in 1949, the Soviet Union vetoed the bid, dismissing the Himalayan kingdom as not truly sovereign.

Yet through these centuries of imperial contests, Nepal’s identity was forged in its ability to maneuver between larger powers.

Whether through the Ranas’ alliance with Britain, the Panchayat monarchy’s delicate Cold War balancing, or post-1990 democratic governments’ opportunistic diplomacy, Nepal’s survival strategy has been less about power than about navigating the tides of others’ ambitions.

The return of geopolitics

In the early 21st century, geopolitics has returned with a vengeance. The 9/11 attacks redrew America’s global engagement, giving birth to security-linked aid packages like the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC).

Meanwhile, China’s spectacular rise culminated in Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a sweeping infrastructure-and-influence program stretching from Central Asia to Africa—and, crucially, into Nepal.

The United States, seeking to counter Beijing’s expanding influence, rebranded its Asia policy into the “Indo-Pacific Strategy,” with India positioned as a pivotal partner.

Economic frameworks like the G7’s Build Back Better World (B3W) and security alignments like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) and AUKUS were layered on top.

China responded by deepening its Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and floating new initiatives like the Global Development Initiative (GDI).

Nepal, caught in the middle, signed both the BRI framework with China and the MCC compact with the United States—moves that have divided its political class and exposed the risks of strategic overextension.

At home, street protests framed these projects not as development initiatives but as Trojan horses for foreign agendas.

In effect, the debate over whether to accept a transmission line project or a cross-border highway became a referendum on whether Nepal’s future lay with Washington or Beijing.

India in the ‘middle of the middle’*

No discussion of Nepal’s geopolitics is complete without India. Bound by history, geography, and culture, the two nations share an open border, intertwined economies, and millions of intermarriages.

Five civilizational ties—Gotra (clan lineage), Gayatri (spiritual heritage), Gai (sacred cow), Ganga (holy river), and Gaya (pilgrimage)—bind daily life across the frontier.

Yet the relationship is as fraught as it is intimate. From water treaties to trade blockades, Nepal has long felt the heavy hand of Indian influence.

Delhi, for its part, views Nepal as a natural sphere of influence—a northern frontier vital to its security.

But India’s own position has become complicated. Economically intertwined with China despite border clashes, reliant on Russian arms even as it deepens military ties with the US, India finds itself pulled in multiple directions.In this mul

tipolar tug-of-war, Kathmandu must navigate not one giant but three.

Civilizational geopolitics

What makes Nepal’s predicament even more complex is that geopolitics today is no longer only about territory and resources. It is increasingly about narratives, civilizations, and identities.

Social media platforms—TikTok, X, YouTube—have become new battlefields where minds are contested as fiercely as mountains or trade routes.

For Nepal, this means development and democracy themselves risk becoming geopolitical tools. Foreign aid—once viewed as neutral—now comes with ideological strings attached.

Infrastructure projects can as easily redraw allegiances as they can lay highways. Even history has become politicized: Was Prithvi Narayan Shah a unifier or a conqueror? Was Buddha a Nepali or an Indian?

In these debates, civilizational pride intersects with strategic positioning, often leaving the country more polarized than united.

A Disconnected future?

Despite its rich connected history, Nepal risks a disconnected future. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has withered under India-Pakistan rivalry.

Globalization has reoriented Nepal’s engagements outward—more families now have ties to Boston or Sydney than to Banaras.

Remittances from the Gulf and the West make up nearly a third of GDP, embedding Nepal in faraway economies even as its politics remain mired in local patronage.

Domestically, Nepal’s political class has too often used foreign policy as a tool for regime survival rather than national strategy.

The Ranas leaned on Britain, the Panchayat monarchy courted China and the US, and today’s democratic leaders tilt toward whichever power suits their partisan needs.

The result is a foreign policy that is reactive, fragmented, and vulnerable to external manipulation.

The new ‘Cold War’ and Nepal’s dilemma

As the Indo-Pacific becomes the new theatre of great power rivalry, Nepal’s stakes are rising. The specter of a “new Cold War” between the US and China may not split the world as neatly as the old, but it risks turning Nepal into a geopolitical flashpoint once again.

For Washington, Kathmandu is a partner in safeguarding liberal values and keeping China’s influence at bay. For Beijing, Nepal is both a strategic buffer against India and a node in its Himalayan outreach.

For Delhi, Nepal is inseparable from its own security. Each sees Nepal as more than a small Himalayan state. For some, it is a frontline; for others, a buffer; for still others, a prize.

The danger is that in the jostling of these ambitions, Nepal’s own agency is lost. Can Nepal escape the prison of geography?

Tim Marshall, in his bestselling ‘Prisoners of Geography,’ argued that small states are trapped by their maps. Nepal’s challenge is to prove him wrong. That requires more than nostalgia for non-alignment or hollow slogans of independence.

It requires a sober assessment of threats, a pragmatic balancing of opportunities, and the courage to say no when projects undermine sovereignty.

Nepal must balance, not bandwagon. Its leaders need to focus less on which side to join and more on how to maximize bargaining power—extracting infrastructure from Beijing, market access from Delhi, and investment from Washington, without mortgaging sovereignty to any.

This also means foreign policy must stop being street politics.For three decades, foreign agreements have been dragged into partisan feuds and mass protests.

In a region where great powers compete ruthlessly, such performative politics is a luxury Nepal cannot afford.

Nepal’s tightrope between giants

Wedged between India and China and increasingly courted by the United States, Nepal finds itself more geopolitically visible than at any point in its modern history.

This heightened interest presents opportunities for investment and global engagement, but also risks entangling the small Himalayan republic in the rivalries of much larger powers.

The challenge for Nepal is not new, but it has become sharper since 2008, when the abolition of the monarchy shifted control of foreign policy to elected governments.

What might have been a democratic consolidation of diplomacy instead coincided with a decade of political and constitutional turmoil.

The 2015 constitution was expected to deliver stability. Yet even after elections in 2017, successive coalitions have been short-lived, leaving Kathmandu often reactive rather than strategic in its international dealings.

Nepal’s geographic location is both an asset and a burden. Policymakers stress the importance of sovereignty, independence, and non-alignment.

As Mrigendra Karki of the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies puts it, “Nepal must balance relations with India and China while diversifying global partnerships with the US, Europe, Japan and Russia.” But that principle is easier to state than to execute.

Relations with India remain vital but fraught. The 2015 blockade, following Kathmandu’s constitutional changes, deepened mistrust and pushed Nepal closer to China.

Historical sensitivities—over trade dependence, security, and disputed territories such as Kalapani and Lipulekh—linger.

Though ties with New Delhi are indispensable for economic and cultural reasons, political trust remains fragile. China, meanwhile, has advanced its agenda through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), focusing on airports, hydropower, and a proposed trans-Himalayan railway.

Politically, Beijing has pressed Kathmandu to curb Tibetan activism while presenting itself as a stable, non-interfering partner.

For many Nepalis, China offers a counterbalance to India’s dominance, though concerns about debt, feasibility of mega-projects, and lack of transparency persist.

The United States, geographically distant but strategically attentive, has increased its role through development aid and its Indo-Pacific strategy.

The $500m Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) agreement on infrastructure was hotly debated in Kathmandu, with critics warning of sovereignty risks.

Washington’s emphasis on democracy and the rule of law contrasts with China’s transactional pragmatism, placing Nepal squarely in the middle of competing strategic visions.

Analysts argue that Nepal must move beyond “emotional” diplomacy—defined by historical affinity or ideological posture—and adopt a pragmatic, interest-based approach.

As political scientist Chandra D. Bhatta notes, “the era of emotional relationships between states is over; national interest must drive diplomacy.”

For Nepal, this means strengthening economic diplomacy, protecting its citizens abroad, leveraging the diaspora more effectively, and pursuing multilateral engagement on issues like climate change.

As global geopolitics grows more uncertain—with elections in India and the US, conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, and the tightening embrace of geo-economics—Nepal’s room for manoeuvre is narrowing.

To succeed, it must overcome its “small country syndrome” and project itself as a democratic, progressive state that can engage giants on equal terms.

For now, Nepal remains at once more visible and more vulnerable. Its future will depend less on external suitors than on whether its leaders can finally craft a coherent foreign policy that turns geography from a trap into an opportunity.

Small states, big choices

In the 21st century, geopolitics is no longer just the domain of empires. Tech companies, diasporas, even individuals now shape global alignments. But for Nepal, the fundamentals remain stubborn: two boulders, one yam.

The choices ahead are stark. Tilt too far toward China, and Nepal risks alienating its largest trading partner, India, while inviting Western suspicion.

Lean too close to India, and it risks repeating history’s suffocating embrace. Rely too heavily on the US, and it may be dragged into a rivalry it cannot afford.

And yet, for all the constraints, Nepal is not without agency. History shows that small states can punch above their weight by skillfully navigating divides.

The challenge is less about choosing sides than about refusing to be chosen for one. As the world enters an era of fractured alliances, civilizational contests, and technological wars, Nepal’s survival once again depends on what it has always done best: walking the tightrope between giants.

Whether it can do so in a way that preserves both sovereignty and development will define not just Nepal’s future, but also the balance of power in Asia’s heartland.

Wedged between Asia’s two giants and eyed by America, Nepal has little choice but to live by balance. China courts Kathmandu through the Belt-and-Road, India through trade, hydropower and open borders, and Washington via development compacts dressed as strategy.

Each insists its role is benign; each expects Nepal to lean its way. Too often, Nepali politics indulges in conspiracy, blaming every protest or policy on outside plots.

In truth, foreign powers do not control Nepal—but they do shape its margins for manoeuvre. Beijing wants calm borders, Delhi wants pliancy, Washington wants presence. None can have it all.

Nepal’s only escape from perpetual vulnerability is smart hedging: extracting infrastructure, markets and aid from all, while keeping sovereignty intact.

Geography cannot be changed. But with deft diplomacy, it can be turned from a curse into leverage.