KATHMANDU: Since September 12, Nepal has been governed by an interim cabinet led by former Chief Justice Sushila Karki—installed in the wake of the Gen Z uprising and tasked with anti-corruption campaign and overseeing elections slated for March 5.

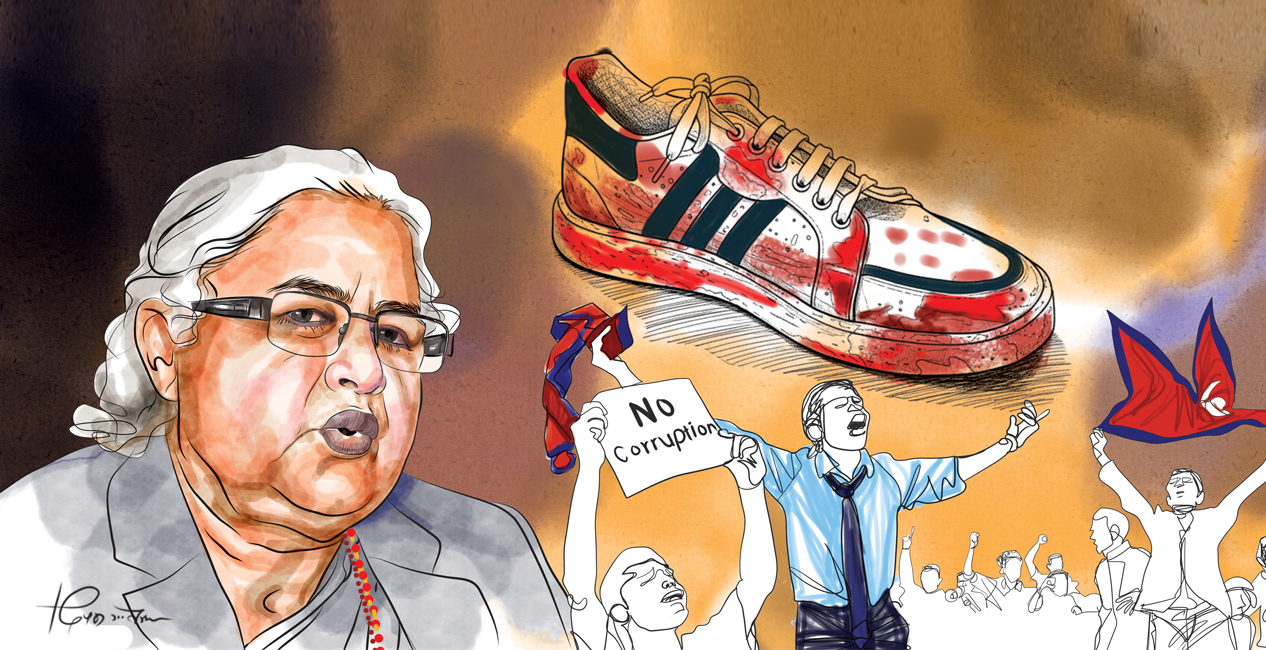

The protests of September 8–9, which left 75 people dead and paralyzed the capital, thrust an angry and idealistic generation into the centre of Nepal’s political stage. A month later, the country remains adrift: political parties are disoriented, institutions uncertain, and the promise of reform increasingly fragile.

Karki’s government was expected to focus on two priorities—elections and anti-corruption measures. Yet, so far, no major corruption files have been opened, and the bureaucracy remains paralysed. The old political guard—within the Nepali Congress, UML, and Maoist Centre—has shown little willingness to yield power. Their grip on state machinery continues to frustrate efforts to clean up governance.

Corruption remains Nepal’s most corrosive problem. It distorts policy, drains public trust, and hollows out institutions. But the new government has yet to move decisively.

The Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), the country’s supreme anti-graft watchdog, has long functioned less as an enforcer than as a retirement home for party loyalists bureaucrats. Without structural reform of such bodies—and the political will to pursue big corruption cases—the interim government risks becoming yet another caretaker of dysfunction.

Nepal’s governance crisis is not just administrative — it’s moral and structural. Gen Z’s uprising offers a rare moment to rethink the country’s social contract and to design a system that truly serves the people, not the powerful.

The political momentum that seemed poised to offer an alternative to Nepal’s traditional parties has begun to wane. Distrust, personal rivalries, and public accusations among the movement’s prominent figures have left the nascent political forces directionless.

The Gen-Z movement awakened a potent desire for change, the lack of coordination, strategy, and coherent leadership has diluted its impact. Public dissatisfaction remains high, yet it risks being misdirected or dissipated. Without a clear policy direction and unified leadership, the energy of the movement—once a formidable challenge to Nepal’s entrenched political order—risks devolving into disillusionment and uncertainty.

Nepal’s Gen Z protesters are not demanding cosmetic change or a simple change of government—they are calling for a fundamental reset of governance. Their uprising was less about replacing prime minister than about rejecting a system that has long rewarded corruption, incompetence, and cronyism. It was, at its core, a demand for a new social contract that restores trust between citizens and the state.

Yet one month on, confusion reigns. Political parties, state institutions, and even the Gen Z movement itself seem unsure of the path forward. The interim government’s decision to rush into early elections without addressing structural reforms risks compounding the very problems the protests sought to fix.

The corruption-riddled bureaucracy, politicised judiciary and watchdog bodies, and entrenched party networks remain intact.

If the Gen Z generation withdraws its support and the old political forces resist, Nepal could slide into yet another phase of instability. The legitimacy of the interim government would be jeopardised, and the country could enter a new period of political paralysis and uncertainty. Without genuine reform and national consensus, elections alone may not heal Nepal’s deep fractures—they could merely reset the cycle of disillusionment.

Gen-Z momentum in fragments

One month after the September 08-09 protests, Nepal’s Gen-Z movement finds itself at a crossroads. The demonstrations toppled entrenched power, spurred the formation of an interim government, and secured an election calendar.

Yet the generation that galvanized the streets remains divided, its leadership struggling to coalesce around a coherent agenda or electoral strategy. Time has only highlighted the gap between promise and performance as well as a fragmented echo of potential rather than a transformative force.

Gen-Z itself is not monolithic. Sudan Gurung’s Hami Nepal faction has expanded its demands to include the removal of the Chief Justice and anti-corruption officials, while other collectives push for direct election of the prime minister.

The movement’s decentralised and leaderless nature raises questions about bargaining power and sustainability. Fragmentation has already diluted public goodwill, especially after the vandalism of state property on September 9.

The movement’s original victories—challenging corruption, amplifying youth voices, and demanding justice for protest victims—have become diffuse. Opportunistic factions, some with royalist leanings to criminal links, have appropriated the Gen-Z banner.

Last week, the NTK-G group’s planned protest at Maiti Ghar, though eventually cancelled, dominated headlines, illustrating how even aborted actions reverberate through public discourse. Meanwhile, social media amplified individual claims to the Gen-Z mantle, from prominent activists to everyday citizens, while the authorities cracked down on those taking to the streets.

Smaller collectives like the Red Chapter continue prolonged sit-ins, representing martyrs’ families and the injured. Beyond Kathmandu, dozens of groups—ranging from Indigenous Gen-Z collectives to district-level alliances—pursue diverse agendas under the same name. Some advocate for constitutional preservation, others for monarchy-aligned reform, and yet others for direct election of the executive. This kaleidoscope reflects both the movement’s vitality and its organizational fragility.

Mainstream Gen-Z leadership, including figures like Rakshya Bam and Yujan Rajbhandari, is attempting to steer the movement toward electoral influence, prioritizing proper recognition of victims and strategic engagement with the interim government. Yet ambiguity persists.

Groups such as Hami Nepal, led by Sudan Gurung, oscillate between constitutional activism and tactical compromise, while vocal figures like Miraj Dhungana to Purustom Yadhav publicly threaten renewed street protests if demands for a directly elected executive are unmet, despite not participating in initial demonstrations.

Observers argue this fragmentation is natural. The movement is generational, not organisational. Its participants share core grievances—corruption, nepotism, injustice, and structural accountability—but express them across overlapping networks. Decentralisation reflects leaderless energy translating into institutional politics: messy, but expected.

The challenge ahead is consolidating around foundational objectives—credible elections, justice for martyrs, and compensation for the injured—without succumbing to internal rivalry or opportunism. For Nepal’s Gen-Z, sustaining momentum is no longer enough; converting street energy into political influence is the measure of success.

The open conflict between Dharan Mayor Harkaraj Rai (Harka) and Kathmandu Mayor Balendra Shah (Balen) exemplifies this fragmentation. Both had emerged as symbols of public anger before the Gen-Z uprising, yet their clash threatens to undermine the unity the movement once inspired.

Harka, who had sought a role in the post-Oli government, attributes his failure to secure a ministerial post to Balen, whom he publicly denounces as a “foreign broker” and puppet. Balen, meanwhile, maintains a posture of restrained silence, though his supporters actively troll Harka online. Observers have criticized both sides: Harka for excessive personal rhetoric and Balen for a perceived strategic silence.

The movement’s political offspring—the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), born from the independent wave in the 2079 local elections—faces similar uncertainty.

Once expected to hold influence in Prime Minister Sushila Karki’s post-Gen-Z government, the party now appears rudderless.

Its supporters, particularly those aligned with imprisoned leader Ravi Lamichhane, see the current government as complicit in maintaining his incarceration, further eroding confidence. Allegations against Home Minister Om Prakash Aryal, a former legal advisor to Balen, have inflamed partisan social media disputes, some linking old grievances with the present political apparatus.

Other figures have contributed to the instability. Durga Prasai, following a brief jail term after the Tinkune movement’s collapse, has launched repeated attacks against both the Karki government and Balen, portraying them as puppets of foreign powers.

Meanwhile, royalist sympathizers interpret the secularist underpinnings of the Gen-Z movement as an affront to “theistic authority,” heightening the political tension. Even Nicholas Bhusal, who emerged as an anti-establishment protests, has criticized the government for failing to reward movement loyalists.

The Gen-Z movement itself is divided. Three distinct factions have emerged, differing on constitutional reform and protest strategy. Miraj Dhungana, a movement leader, has openly criticized Prime Minister Karki for inaction, threatened resignation, and highlighted the movement’s lack of representation in government.

Amid this fragmentation, traditional parties are regaining influence. Student wings aligned with the UML and other established actors have initiated legal actions against movement figures, signaling a reassertion of conventional power. Meanwhile, the Karki government, originally formed to manage elections, faces mounting pressure: constitutional reforms, high-profile prosecutions, corruption investigations, and reconstruction after floods and post-protest vandalism—all while preparing for elections scheduled on March 5.

Leadership poses the first challenge. Movements alone cannot substitute for governance. Even a popular uprising requires figures capable of translating outrage into sustainable policy. Without unifying leadership, Gen Z risks fragmentation. Collective energy must coalesce around capable individuals who can set a coherent agenda, or its momentum may dissipate.

Nepal’s snap polls: youth vs. old guard

Nepal’s interim government, led by Prime Minister Sushila Karki, has stumbled at its first major test—political consultation ahead of elections. Rather than directly engaging parties represented in the dissolved House, Karki outsourced the task to President Ramchandra Paudel, turning a constitutional duty into a ceremonial gesture.

On Friday (October 10), Paudel gathered party leaders to urge participation in the March 2026 elections, framing them as essential to safeguarding democracy. Yet the absence of top leaders—Deuba, Oli, and Dahal—spoke volumes about the current political unease.

The government’s reluctance to consult directly reflects its uneasy relationship with the Gen Z movement, whose anti-establishment fervour brought it to power. Karki reportedly feared alienating young protesters by appearing too close to the old political elite.

But sidestepping the parties risks undermining electoral credibility. The Congress and UML—the country’s two largest parties—remain divided: the former hesitant, the latter pushing to reinstate the dissolved parliament. Smaller parties demand security guarantees as weapons thefts and lawlessness test state control.

President Paudel has stepped into the vacuum, meeting both Gen Z and party representatives to build consensus. His intervention may have steadied the process temporarily, but it also underscores a deeper institutional fragility—an interim government unsure of its authority, and a political class uncertain whether it still holds the country’s trust.

Nepal’s democracy faces a pivotal test. The Election Commission has set a firm schedule for the March 5 snap polls: parties must register by November 16, first-past-the-post candidates by January 16, and proportional representation candidates by December 1. Clear deadlines, however, clash with a widening standoff between President Ramchandra Paudel and interim Prime Minister Sushila Karki over who should convene traditional parties to build electoral consensus.

Karki, appointed under the mandate of the Gen Z movement that shook the streets on September 8–9, hesitates to invite the Nepali Congress, CPN-UML, and CPN (Maoist Centre) to the table. Some old-guard parties question the legitimacy of the interim government and the snap polls, while others accept them reluctantly. Without compromise, the election timetable is at risk.

The Gen Z movement demands meaningful participation, not token representation. Figures such as Sudan Gurung exemplify the youth’s insistence on a voice in shaping policy, reflecting the broader impatience of a generation frustrated by entrenched leaders. For traditional parties, key figures—Sher Bahadur Deuba, KP Oli, and Pushpa Kamal Dahal—symbolize the failures that ignited the protests; leadership renewal is critical to restore trust.

Both generations face a stark choice: compromise or chaos. Procedural squabbles and mistrust could derail elections, but broad participation can lend legitimacy and stability.

March 5 is more than a date—it is a test of Nepal’s political maturity, where youthful ambition must meet institutional experience halfway to secure a fragile democracy’s future.

The Nepali Congress and CPN-UML now face a choice: pursue legal remedies against the House dissolution or focus on election preparedness. Courts may adjudicate disputes, but legitimacy derives from the ballot. Continuing legal wrangles risks delaying elections and eroding public trust, while timely polls remain the most credible path to reassert authority.

Both parties must also confront structural failings. Long reliant on entrenched hierarchies, they have neglected youth leadership and renewal. To regain relevance, they must cultivate credible young leaders who resonate with a generation impatient with traditional politics.

Nepal’s democracy now balances on this interplay: an energetic, politically conscious youth and institutions willing to respond. The March 5 elections will test whether traditional parties can adapt or be permanently eclipsed. In this new era, only those able to translate reformist energy into accountable, competent leadership will thrive, while inertia risks ceding ground to populism and instability.

A wake-up call, not a cure

The upheaval exposes deeper, systemic challenges. Nepal’s society, argues anthropologist Dor Bahadur Bista, is steeped in fatalism: inequality, inefficiency, and misrule are often accepted as fate. Patronage networks, hierarchical norms, and nepotism further stifle accountability and innovation. Many party cadres dismissed the youth protests, claiming foreign interference—a stark clash between globally aware youth and a conservative older generation.

The Gen Z movement jolted the system, demanding accountability and transparency. But protests alone cannot overcome entrenched social and economic barriers. True transformation will require patient, multi-generational effort: educational reform, institutional accountability, innovation, and cultural change.

The interim government and upcoming elections offer a fleeting window of opportunity—but lasting change will demand persistence, pragmatism, and broad societal engagement. Nepal has been shaken; now it must learn to rebuild.

Uprising shakes economic foundations

Nepal’s economy, already fragile, has been jolted by the country’s most violent unrest in decades.

The World Bank predicts Nepal’s GDP growth will slump to 2.1 percent in the current fiscal year, far below the 5.4 percent forecast in April, with the possibility of contraction ranging between 1.5 and 2.6 percent.

The assessment does not yet include the damage caused by torrential rainfall on 3–4 October, which further battered infrastructure, agriculture, and livelihoods. Tourist arrivals fell 18 percent in September compared with last year, while private investment and non-hydropower construction are expected to slow sharply as investor confidence erodes.

The unrest hit businesses hardest. Hotels, factories, and shops were vandalised or destroyed, disrupting supply chains and putting over 15,000 jobs at risk.

The Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FNCCI) estimates preliminary losses at roughly Rs80 billion. FNCCI President Chandra Prasad Dhakal warns that the attacks send a negative message to investors at a critical juncture: Nepal is attempting to graduate from Least Developed Country status by November 2026, a transition that will require heavy private-sector investment.

“People still do not understand that the private sector creates jobs, pays taxes, and sustains development,” Dhakal said. He called for public awareness campaigns and policy stability to restore confidence.

With national elections scheduled for March 2026—coinciding with the peak tourism season—the private sector is pressing for predictability as a prerequisite for recovery.

Tourism and services are expected to take the deepest hit, with declines in accommodation, transport, retail, and food services. Agriculture is similarly strained; delayed monsoon rains in key rice-producing regions are set to dampen output. The cumulative effect of unrest and natural disasters has deepened political and economic uncertainty, threatening the nascent recovery that saw GDP growth reach 4.6 percent in the fiscal year ending July 2025.

Nepal is not alone. The World Bank notes that social unrest toppled governments in Bangladesh (August 2024) and Sri Lanka (July 2022), with GDP often falling 5 percent in subsequent quarters. High public debt limits fiscal flexibility, while weak investment and rising global tariffs threaten regional growth. Artificial intelligence presents both an opportunity to boost productivity and a risk of labour market disruption.

How the mighty have fallen

Nepal’s political old guard has survived many storms, but the tempest of September 8–9 may prove existential. The bloody suppression of the Gen Z uprising—marked by state gunfire, deaths of young protesters, and the eventual resignation of KP Sharma Oli—shattered the illusion of stability that Nepal’s aging triumvirate had clung to.

A new interim administration under former chief justice Sushila Karki now holds the fort, but the deeper question is whether the same septuagenarian leaders who built Nepal’s modern politics can still claim to lead its future.

Sher Bahadur Deuba (80 next June), KP Oli (74), and Pushpa Kamal Dahal (71) seem united in their refusal to yield. Each has ruled multiple times—Deuba five, Oli four, Dahal three—yet none has delivered enduring governance.

Their careers mirror Nepal’s cyclical decay: revolutions that promise renewal only to end in patronage and paralysis. They were the Gen Z of their own era, the rebels who dismantled the Panchayat and monarchy. But heroes who overstay their welcome risk turning into the very relics they once opposed.

The Gen Z movement, born of frustration with corruption and elite inertia, has changed the political weather. Still, the old establishment has managed to co-opt the crisis, announcing early elections to diffuse momentum.

Dahal’s cosmetic gestures—like dissolving his party’s central committee—are seen more as survival tactics than reform. Oli remains defiant, unrepentant over the bloodshed, while Deuba clings to his chair.

Nepal’s history warns that when leaders refuse to read the writing on the wall, the people will write a new script. From the fall of the Ranas to the monarchy’s end, every entrenched system has eventually collapsed. The Gen Z revolt may not have toppled the old empires yet—but if complacency persists, it has merely paused before the next revolution.

A fragile future

The interim government faces inherent constraints. Hastily assembled and politically untested, it lacks both party backing and broad public legitimacy.

Prime Minister Karki’s swift dissolution of the House of Representatives drew accusations of illegality from deposed Prime Minister Oli, while traditional parties, briefly sidelined, now resist committing to the March elections. Analysts warn that any delay or questions over legitimacy could further unsettle the country.

Security remains fragile. Investigations into September’s protests are contested, with police and judicial commissions at odds, and calls to prosecute senior politicians risk street unrest. The government must navigate a narrow path between accountability and order.

The youth movement, meanwhile, is fragmented. Leaders such as Sudan Gurung and Balendra Shah polarise opinion, with factions pushing competing agendas—from directly elected executives to anti-corruption purges. Political scientist Sucheta Pyakuryal notes that without cohesion or an ideological anchor, the movement risks co-optation and a loss of public trust.

Nepal’s immediate imperative is clear: credible elections, a functioning interim administration, and dialogue between youth and political institutions. Gen-Z’s influence depends on unity and strategic clarity; the government’s legitimacy hinges on managing expectations while respecting the Constitution.

The September uprising exposed both the potential of an engaged youth and the fragility of Nepal’s democratic apparatus.

In the months ahead, the movement will either cement meaningful reform or fade as a cautionary tale of dissipated momentum.

As activist Raskshya Bam observes, the priority is unity and dialogue: the protests sought not to exclude political parties, but to make the system accountable, transparent, and responsive to a restless generation.

Nepal’s experience underscores the delicate balance between political energy and economic stability. Popular uprisings can catalyse reform, but they carry immediate economic costs.

The country’s young population, high unemployment, and structural constraints—bureaucratic unpredictability, inadequate infrastructure, and high trade costs—compound the challenge. Analysts warn that without policy consistency, investor confidence, and a clear post-crisis roadmap, the energy unleashed by Generation Z risks dissipating, leaving a landscape of uncertainty rather than opportunity.

The interim government’s predicament is compounded by timing. With the Election Commission setting 16 November as the deadline to register new parties for 5 March polls, youth factions must decide whether to align with existing parties, form a new political entity, or contest independently.

Past examples, such as the RSP’s brief electoral surge in 2022, demonstrate both the potential and pitfalls of youthful, digitally mobilised campaigns. Yet without institutional alliances, long-term reform risks stalling.

Observers stress that political change cannot bypass existing institutions. The naivety in expecting transformation solely through street pressure: negotiation with reform-minded actors within established parties remains essential.

Clarity of intent—whether the movement seeks active political office or civic advocacy—will determine the Gen-Z cohort’s leverage.

The narrow window for meaningful engagement is closing, but careful strategy could allow young Nepalis to institutionalise reforms, influence elections, and strengthen democratic accountability.

Populist slogans cannot substitute for concrete plans. Nepal’s history of economic mismanagement—decades of fiscal negligence following technocratic interludes—illustrates the stakes.

Entrenched political forces remain formidable. Even if Gen Z forms a credible electoral bloc, established parties can unite to block newcomers. Rural voters, party machines, and the spread of disinformation complicate efforts to convert protest into governance. Revolutions without delivery, as past Nepali movements have shown, risk collapse or co-optation.

Knowledge of government, policy, and political negotiation is indispensable for sustaining reform. While youth energy has awakened the public, only leaders with both vision and competence—willing to challenge orthodoxy or forge new paths—can convert protest into lasting institutional change.

Without such figures, Nepal’s democracy remains vulnerable to populist forces: energetic, visible, but ultimately unaccountable.

Nepal’s post-September landscape is the one of paradox: a movement that toppled complacent elites but faces internal divisions; an interim government navigating urgent expectations while constrained by law; and a society eager for immediate results yet dependent on patient, structural reform. How the youth respond, and whether they consolidate their fragmented energy into lasting political influence, may define the country’s governance trajectory for years to come.