Imbalance between number of schools and students leaves 900 schools with fewer than 10 students

On 11 February 2026, when Nepal News reached the gate of Ganga Primary School in Timalbesi, Panchkhal Municipality-13, Kavre, it was 11:30 a.m. The national flag was flying at the school gate. The school, surrounded by walls and barbed wire, was deserted. Among the four children in the schoolyard, some were lying on the ground while others were sitting cross-legged. They had a few books and study materials with them. Teacher Junu Acharya was checking the students’ homework while sitting on a chakati (traditional mat). Office Assistant Kumar Pandey was observing the activities of teachers and students while enjoying the winter sun. At first glance, the scene looked like a tuition class. But over the past few years, as the settlement dwindled, Ganga Primary School has become almost student-less.

After the government adopted a policy to merge or adjust schools with low student numbers into nearby government schools, Ganga Primary School was merged two years ago with Ram Secondary School nearby. Ram Secondary School is located near the ward office of Panchkhal Municipality-13, about an hour and a half walk from Ganga Primary School. Children who cannot reach the school and have no alternative for learning are still taught at Ganga Primary even after school merger. “The records of these children are at Ram Secondary, but because they cannot walk uphill to Ram Secondary, we have to teach them here,” says teacher Acharya.

Students learning in the courtyard of Ganga Primary School

Currently, Ganga Primary has become like a branch of Ram Secondary School. According to office assistant Pandey, who has worked at Ganga Primary School for 24 years, the school was once full of students, with around 200 in a single academic session. Now, there are only four children. In the Early Childhood Development (ECD) center, there are three-year-old Swechchha Tamang and four-year-old Sushant Tamang, while in grade 2 there is seven-year-old Barsha Tamang and in grade 3 nine-year-old Manjita Tamang. These four children come from only two families. According to teacher Acharya, until six months ago, only Sushant, Barsha, and Manjita from the same household used to attend school.

Ganga Primary, established on 16 December 1981, occupies four katthas and has seven rooms in four buildings. With the school merged into Ram Secondary School and most students gone, five rooms have been locked. One classroom is used for teaching, and another is for teacher Acharya to stay. School desks and benches are piled up in closed classrooms. In the classroom used for children, there are a few old and broken desks. Teacher Acharya teaches children of different grades and ages in a single classroom. During cold weather, she teaches in the courtyard, otherwise inside the classroom.

When asked why the school that had already been merged with another school remains open for only four children, both parents and teachers share nearly the same opinion. They commonly feel that practical necessity has led to Ganga Primary School continuing to operate after the adjustment despite having only four students.

Sushant, Barsha and Manjita with their mother

Officials from the Education Section of Panchkhal Municipality also argue that the school must be run because the young children cannot walk uphill to the nearby school. Uday Prasad Koirala, an officer there, explains, “The arrangement for these children to study down here was made so that ‘no one is deprived of education by the state.””

Indeed, the teachers, students, and the office helper at Ganga Primary are all from Ram Secondary School. Funding for the students’ snacks, salaries and benefits for both the teacher and the office helper, and other related expenses are all disbursed from Ram Secondary School.

A girl child studies in the open in the school’s courtyard

The situation at Ganga Primary near Kathmandu in Kavre district reflects the failure of the government’s school consolidation policy. It shows that the government policy to merge or adjust schools with few students into other schools without alternative arrangements has failed. Educationist Bidyanath Koirala says, “It could have been done with transportation or residential arrangements. Forcing school consolidation like this, causing students to suffer and locking existing school buildings, is wrong.”

An effort from 12 years ago

Due to imbalance between teachers, students, and school numbers, the government began attempts to consolidate schools since 2070 BS (mid-April 2013 to mid-April 2014). According to the School Sector Development Plan (SSDP), grades 1-12 were included in school education. Schools were restructured to create an integrated form of school education, and based on mapping, two or more primary and secondary schools could be merged into one under the ‘School Consolidation Implementation Directive,’ approved by a ministerial meeting on 9 October 2013. Later, it was revised and issued as the ‘Public School Consolidation and Integration Program Implementation Procedure, 2020,’ which provides for the consolidation and integration of both community and private schools.

After implementation of the Procedure on 24 May 2020, as many as 1,830 community schools have been closed. According to the Economic Survey 2076/77 BS (2019/20), before the procedure, there were 27,704 community schools nationwide; by academic year 2081 BS, the number dropped to 25,874. The reduction is due to consolidation and closure. Journalist and educationist Laxman Upreti says, “As student numbers dropped, the costs for schools increased, and the government turned to consolidation. But they ignored geographic remoteness and children’s difficulties, which is why the policy has not succeeded.”

Teacher Junu Acharya and her four students

The 2077 Procedure mentions that school consolidation would be based on commuting time, student numbers, and population. Travel time is considered a major factor for consolidation. Schools reachable by walking or school bus in less than half an hour would be merged into another school offering higher grades. Similarly, hill schools with fewer than 30 students, mountain schools with fewer than 45, and Terai/valley schools with fewer than 60 students in grades 1-3 would be consolidated into nearby schools. For grades 1-5, mountain schools with fewer than 50, hill schools with fewer than 75, and Terai/valley schools with fewer than 100 students would also be merged. School closure also requires low household numbers and low population growth.

The government’s guidelines also include provisions for providing residential facilities for students who live far from school. When issuing these guidelines, the government expected that aligning teacher positions with school adjustments would ensure the availability of subject-specific skilled teachers in larger schools, improve the learning environment, and enhance educational quality. After school adjustments, the government had even announced that schools would receive incentive grants ranging from a minimum of 2 million to a maximum of 6 million rupees per school to encourage improvements in educational quality. However, the guidelines issued without proper budget arrangements have proved problematic for the government itself. Educationist Koirala notes that the school adjustment guidelines were impractical, as they were implemented hastily without thorough discussions and groundwork with local authorities. He says, “The central government did not understand federalism, the Village and Municipal Federation did not play a strong role in policy-making, the ministry staff passed what they had written, and during implementation, it became impractical in many places.

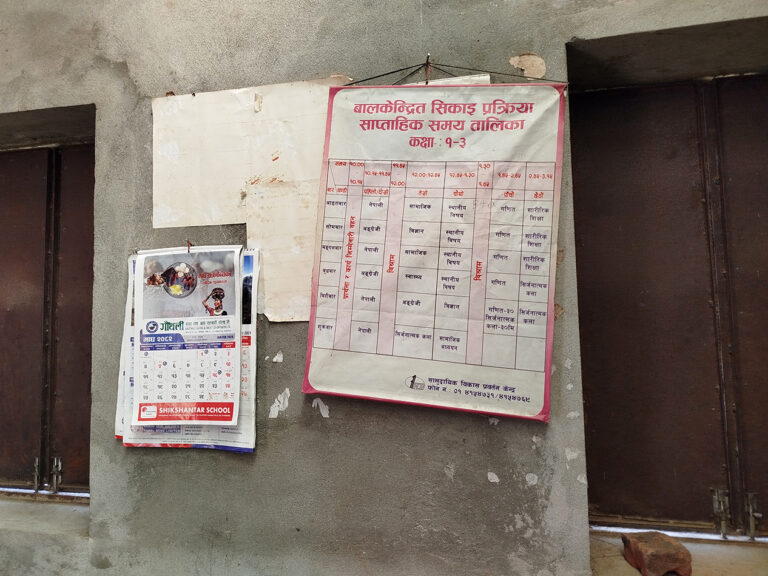

A time-table hung on the wall of Ganga Primary School

According to Nilkantha Dhakal, Director of the Center for Education and Human Resource Development, the government has been unable to provide the announced incentive funds because many schools across the country applied for school adjustment. The Center reports that in the fiscal year 2077/078 (2019/20) alone, 1,203 schools applied for adjustment. To provide the announced incentive funds to these schools at the declared rates, the government would have needed at least 2.92 billion rupees. However, that year, the government allocated only Rs 850 million, effectively undermining its own program.

Even in the government’s policy and programs for fiscal year 2082/83 BS (2025/26), sufficient incentive budget has not been allocated for school adjustments. This time, the government has set aside only 450 million rupees as incentive funds for school adjustments. The Center for Education and Human Resource Development had called on all local governments on 21 December 2025 to submit school adjustment proposals by mid-March 2026. However, if a large number of schools apply for adjustment, many schools are certain to be excluded from the incentive grants.

Indeed, according to the previous guidelines, the lack of budget to provide incentive funds has forced the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology to develop new standards for school adjustments. Nilkantha Dhakal, Director of the Center, says, “Based on lessons learned so far, the preparation of new standards is underway and in the final stage.” According to him, once the new standards for school adjustment are issued, the old standards will automatically be repealed.

Desks and benches inside a lockeed classroom

The Ministry of Education has delegated the responsibility of implementing school consolidation procedures to local governments. According to the Local Government Operation Act, 2017, local authorities can manage teacher deployment, staff allocation, mapping, approval, licensing, consolidation, and regulation of community schools. Director at the ministry, Hari Prasad Aryal, says local governments can adapt procedures according to geography. “If geography makes access extremely difficult and children cannot attend, closing the school is not the solution. Practically, you must consider literacy; otherwise, local authorities have the right to close or maintain schools under the procedure,” he says.

Timalbesi

Low-student schools that are merged or closed often leave infrastructure abandoned. Some merged or closed school buildings are used for pre-primary classes or community study centers, while others are left idle. Communities, emotionally attached to land and buildings they donated and built, often resist school consolidation. Aryal says, “That’s why schools are sometimes preserved by reducing levels or running ECD classes. Closure is not always mandatory.”

Schools saved by communities

In Baglung Municipality-12, the Kaligandaki Primary School was saved from closure because it has four ECD students, even though there are no grade 5 students in the primary level. “The ECD children are very young, and they cannot walk a long distance. Since they can study at home, the school was preserved,” says Ward Chair Kopilamani Sharma.

There were three teachers at Kaligandaki Primary School. One of them retired. Another was transferred to Lakshminarayan Basic School, which is half an hour away from Kaligandaki, while the third teacher is already at that school. Recently, due to a decline in birth rates, the school has not had students, according to Ward Chair Sharma. He adds, “The school must also be maintained in the hope that students will come in the future. At one point, up to 25 students used to enroll in a single academic session at the school, which was established 12 years ago. Now, the number has decreased.”

Similarly, in Baglung Municipality-13, Laxminarayan School, which offers education up to grade 3, has had no students for three years. According to Ward Chair Narayan Prasad Sharma Paudel, this school, established in 2051 BS (1994/95), once had up to 25 students studying Sanskrit. Even though teaching was halted due to lack of students, the school was spared from consolidation. Paudel argues that the school is preserved for future students. “If students come, they should be taught. These are structures from 2052 BS (1995/96) – how can we abandon them?” he asks.

In recent years, migration and declining birth rates have reduced student numbers nationwide. According to the education ministry, there are 336 community schools with fewer than five students, 900 schools with 6–10 students, 2,561 schools with fewer than 20 students, and 15,000 schools with fewer than 100 students. This imbalance between students, teachers, and schools has become a complex problem for government schools. Therefore, it is time for the government to review policies on teacher deployment, school mapping, and consolidation. Educationist Binay Kumar Kusiyat says, “It is time to revise the government’s school consolidation policy, set a minimum five-year target for consolidation, and ensure political commitment.”