Eight governments in ten years after new constitution, top leaders shattered aspirations of ‘New Nepal’

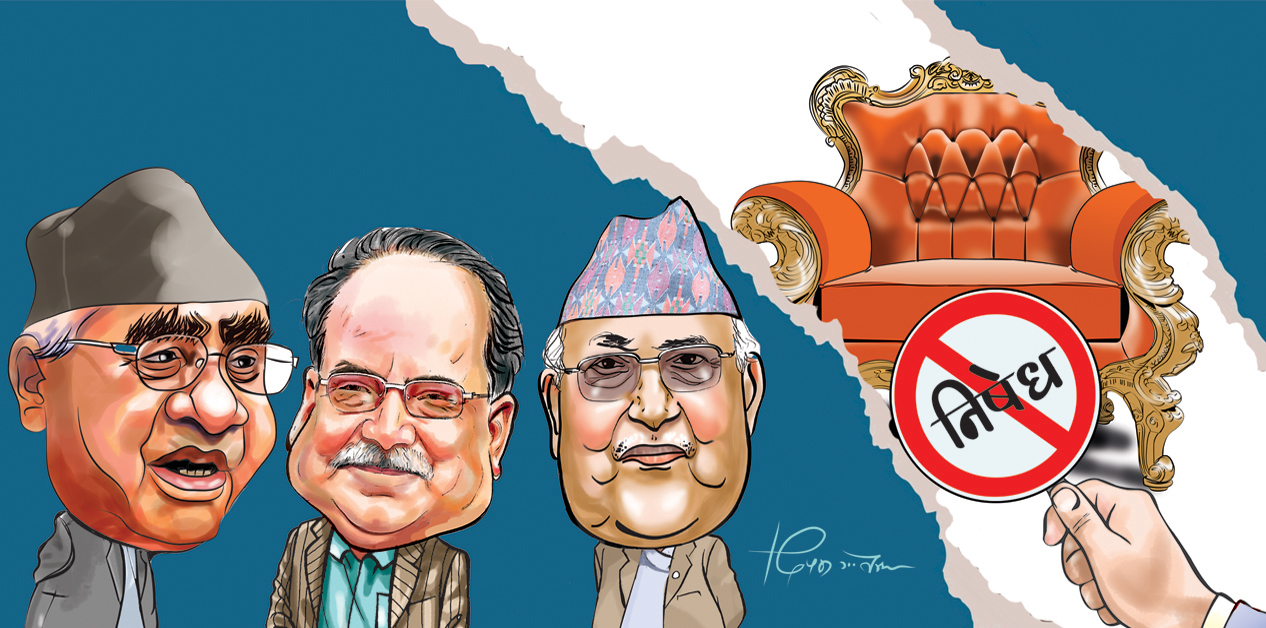

KATHMANDU: The main targets of the Gen Z movement have consistently been the top leaders of the Nepali Congress, CPN (UML), and CPN (Maoist Center), who have long dominated power. Currently, social anger against the chief leaders of these traditional three parties has intensified. The pressure on the three-party leaders to resign from their positions has increased.

Repeatedly serving as Prime Minister, Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba, CPN (UML) Chairman KP Sharma Oli, and Maoist Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal, despite alternating in power, have failed to fulfill public aspirations, which has drawn Gen Z’s ire against them. The residences of the trio were set on fire, and Deuba and his wife Arzu Rana even faced physical attacks.

In the last decade, there was a cycle of Oli, Deuba, and Dahal taking turns to become Prime Minister. Following the demand of the Gen Z movement, the formation of an interim government under former Chief Justice Sushila Karki has temporarily halted this revolving cycle of the three leaders occupying the premiership.

Nepal News had previously documented how Deuba, Oli, and Dahal turned the Prime Minister’s seat into a kind of ‘musical chair’ over the past decade.

The tendency of the three top leaders to rotate governance is not entirely surprising. Before the 2017 elections, UML and Maoist formed an electoral alliance. Both parties had announced that they would merge after the elections. UML Chairman Oli stated that since the two leftist parties were in a single front, they were now in a strong position to win elections for a long time. In his campaign speeches, he repeatedly asserted that Sher Bahadur Deuba would be the last Prime Minister from Nepali Congress.

However, less than eight years later, Oli’s stance underwent a complete 180-degree shift. He became Prime Minister with the support of Deuba and repeatedly reaffirmed his commitment to hand over power to Deuba, who he had previously declared would be the ‘final Prime Minister.’

Due to the agreement between the two parties, Deuba was preparing to assume the leadership of the government for the sixth time starting from July 2026 with the support of UML.

On July 1, 2024, UML and Congress had reached a seven-point agreement, stipulating that the first two years of government leadership would be under UML, and the remaining term would be under Congress.

Oli’s commitment to hand over power to Deuba, though appearing as adherence to the agreement, is actually a continuation of the transaction-driven politics of power over the past decade. Since the promulgation of the Constitution in 2015, a cycle of alternating governance has operated among Oli, Deuba, and Pushpa Kamal Dahal. All three have been swapping the Prime Minister’s chair for their own advantage, with political equations continuously forming and collapsing to facilitate this.

Political analyst Devraj Dahal comments that the power syndicate of the three top leaders became firmly established, but it failed to deliver development and good governance. He says, “There was an unofficial syndicate of Oli, Deuba, and Dahal in power. Ironically! None of the three could deliver. There was a lot of talk, but no delivery.”

To such an extent that the three top leaders would take any step necessary to become Prime Minister, forming alliances whenever and with whomever they needed. This is what kept them in the Prime Minister’s seat in rotation. Dahal adds, “During this time, many scandals occurred. Because the three leaders’ interests aligned, no one faced any accountability.”

Even though the country’s governance has always been centered on these three, they have been unable to bring about economic, social, or political transformation. Their only focus has been how to reach the chair and how to stay in power for as long as possible.

Political analyst Devraj Dahal comments that the power syndicate of the three top leaders became firmly established, but it failed to deliver development and good governance.

Dahal says, “A democratic country empowers its citizens; it does not make them servants of foreign powers. Today, as many young people have migrated abroad, ordinary citizens feel extreme despair and anger. No leader has been able to take proactive steps to reduce this.”

If the top leaders had alternated in government while also working to push forward economic and social reforms, they could have significantly changed the country. Since they played an important role in promulgating the Constitution, there was an opportunity to reshape the nation.

At that time, the UML-Maoist alliance even had a two-thirds majority in 2017. Until the Gen Z movement, the Congress-UML alliance was also powerful. The three leaders failed to provide service delivery, good governance, and development. “The Congress-UML alliance had the numbers and power to push forward broad reforms,” says Samriddha Ghimire, Director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, “but the alliance government did not advance work as it should have.”

Alliance of self-interest

After the new Constitution was promulgated the top three party leaders declared that the country would achieve political stability and focus on economic and social development. However, these declarations were never implemented. Instead, the game of reaching power by any means kept politics unstable.

Political analyst Geja Sharma Wagle notes that since the three leaders prioritized themselves in decision-making, no alliance could achieve stability. He says, “The tendency of the three top leaders to make any kind of decision for personal gain has ruined the country.”

Since the Constitution’s promulgation, two general and two local elections have taken place. Of the eight federal governments formed during this 10-year period, none completed a full five-year term. Even the two-thirds majority government formed after the UML-Maoist unification collapsed midway. Political instability and the recurring cycle of forming and dissolving governments has continued even after the new Constitution. A hung parliament has become a chronic problem.

Out of the 3,643 days since the new Constitution came into effect (as of September 9), Oli has been head of government for 2,055 days. Congress President Deuba led for 834 days, and Maoist Chairman Dahal for 877 days. During this period, Oli has governed the longest among the three leaders.

Political analyst Geja Sharma Wagle notes that since the three leaders prioritized themselves in decision-making, no alliance could achieve stability.

Even though there were changes among coalition parties, the “musical chair” of power has never moved beyond these three leaders.

Oli led a multi-colored coalition of a dozen parties, even forming a government with nearly a two-thirds majority. He had the opportunity to lead a government between the first and second largest parliamentary parties. After the Constitution was promulgated on September 20, 2015, an Oli–Dahal coalition was formed, but it did not last long. Later, a Dahal–Deuba coalition emerged. While Dahal was cooperating with Deuba, he also formed an electoral alliance with Oli.

After losing government in 2016, Oli became more aggressive. Until the announcement of the electoral alliance, he was a staunch critic of the Maoists. Professor Krishna Pokharel says that after the local elections, Oli joined hands with the Maoists solely to return to power. “Oli had claimed that the Maoists were finished. He even attended Rastriya Prajatantra Party events, praising RPP as a new force. Later, he allied with the Maoists,” Pokharel adds.

During the unification of UML and Maoist, there were deep internal conflicts. The two parties merged to form the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN), a unity focused on gaining power. That’s why it didn’t last long. Before party unification, Oli and Dahal had agreed to split government leadership evenly, but that agreement was never implemented, and the CPN unity did not continue.

While Oli was Prime Minister from the CPN, he issued ordinances to loosen political party division rules. Until then, the law required 40% support in the central committee and parliamentary party to split a party. The ordinance reduced it to only 40% in one group, making it easier for Oli to consolidate power.

Deuba further loosened the new rules, lowering it to 20%. With his facilitation, UML split, forming the CPN (Unified Socialist) under Madhav Kumar Nepal, which joined Deuba-led government. Among the three leaders, competition involved taking such reverse steps to place themselves in power and remain there.

Oli led a multi-colored coalition of a dozen parties, even forming a government with nearly a two-thirds majority. He had the opportunity to lead a government between the first and second largest parliamentary parties. After the Constitution was promulgated on September 20, 2015, an Oli–Dahal coalition was formed, but it did not last long.

The Supreme Court also ruled that the CPN split could proceed smoothly amid internal party conflicts. Once the CPN reverted to its pre-unification state, the UML and Maoist parties became fragmented. Then a new Deuba–Dahal coalition was formed, which included other parties as well. Dahal, having parted ways with Oli, played a key role in making Deuba the Prime Minister. The government formed in this manner eventually conducted local and general elections in 2022.

After the elections, friction began between Deuba and Dahal. Dahal, chairman of the Maoist party that won 32 seats, moved ahead to become Prime Minister himself. After Deuba’s reluctance, Dahal aligned with Oli, whom he had previously criticized before the elections. By playing the game between the first and second largest parties, he managed to snatch the Prime Minister’s chair. It was an unusual event.

Three months later, when it was time to elect the President, a new Dahal–Deuba coalition emerged. That relationship also did not last long. Dahal once again shifted toward Oli. In March 2024, UML and Maoist Centre reached a seven-point agreement, with Congress separating from the power-sharing arrangement with the Maoists.

The relationship between Oli and Dahal had been tense during the CPN era. After the 2022 elections, some analysts observed that the relationship improved when Dahal became Prime Minister with Oli’s support. However, Oli, who had declared a commitment to “go to heaven and hell together,” suddenly replaced Dahal. Ultimately, he became Prime Minister for the fourth time on July 15 2024 under the agreement between Congress as the first party and UML as the second party in Parliament. “Oli’s political cunning is evident. Even when there was a coalition between Maoists and Congress, Oli proposed joining the government under Congress’s leadership. But when it came time to lead the government, Oli moved ahead himself,” says Director Samriddha Ghimire.

Same Face, Same Instability

Many had expected political stability after the Constitution was promulgated. Yet, despite changes in the Constitution, governance system, and administrative structure, the country remains trapped in the old misfortune of governments changing frequently. After 1991, before King Gyanendra Shah seized power, twelve governments were formed and dissolved until February 1, 2005.

When it was time to elect the President, a new Dahal–Deuba coalition emerged. That relationship also did not last long. Dahal once again shifted toward Oli. In March 2024, UML and Maoist Centre reached a seven-point agreement, with Congress separating from the power-sharing arrangement with the Maoists.

Girija Prasad Koirala led four governments, Deuba three, Lokendra Bahadur Chand and Surya Bahadur Thapa two each, and Manmohan Adhikari and Krishna Prasad Bhattarai one each. These governments were either majority, minority, or coalition administrations. Unfortunately, even though Congress won a full majority in the 1991 and 1999 elections, Koirala and Bhattarai were unable to complete their full terms.

Koirala led the government during the 2006 transitional period after the Maoists joined the peace process. Following the first Constituent Assembly election, governments were led by Dahal, Madhav Kumar Nepal, Jhalanath Khanal, and Baburam Bhattarai. The second Constituent Assembly election was conducted under the government led by then Chief Justice Khil Raj Regmi. After that election, Sushil Koirala became Prime Minister. From the formation of the first Constituent Assembly until the Constitution was promulgated, six governments changed.

After the Constitution was announced, Oli became Prime Minister with the support of 12 parties, ranging from the purist communist Rastriya Janamorcha to the royalist Rastriya Prajatantra Party Nepal. Ironically, even the government led by Oli, supported by a dozen multi-colored parties, did not survive long.

Oli, Deuba, and Dahal exhibit a shared tendency of not allowing anyone else to lead the government. When the CPN dispute peaked in 2020, a proposal was made to appoint Constituent Assembly Chair Subas Nembang as a consensual Prime Minister instead of Oli, which Oli outright rejected. UML has been unable to put forward any other leader in place of Oli.

In Congress, General Secretary Gagan Kumar Thapa contested the parliamentary party leadership against Deuba, yet, Thapa did not receive support from some leaders within his own faction. In the Maoists, anyone challenging Dahal’s dominance was forced to leave the party. After the Gen Z movement, the country’s political landscape changed, but unfortunately, there is no sign that the three top leaders will retire.

Shared character – Abuse of power

Another commonality among the three top leaders is the abuse of power and authoritarianism. Among them, Oli is at the forefront. He does not hesitate to take any step or make any agreement for his own benefit. Political analyst Wagle points out that Oli has exerted undue influence over constitutional bodies, from Parliament to the courts, for the sake of power. “The people themselves experienced how Oli even misused the President. In the past, Deuba created a poor record by dissolving the elected Parliament. Therefore, abuse of power is a shared trait of both Oli and Deuba,” he says.

When Oli became Prime Minister last time, he sent an ordinance concerning the Constitutional Council, which was immediately issued by then-President Bidya Devi Bhandari. Shortly afterward, Oli convened a council meeting and appointed his close associates to constitutional bodies. The council’s decision, opposed everywhere, led to the Supreme Court’s Constitutional Bench verdict becoming the center of controversy and doubt.

Oli, Deuba, and Dahal exhibit a shared tendency of not allowing anyone else to lead the government. When the CPN dispute peaked in 2020, a proposal was made to appoint Constituent Assembly Chair Subas Nembang as a consensual Prime Minister instead of Oli, which Oli outright rejected.

Oli, together with Bhandari, dissolved the House of Representatives twice. The first dissolution, on December 20, 2020, was annulled by the Supreme Court on February 23, 2021. He dissolved Parliament a second time in May 2021. The Supreme Court annulled this decision on July 8, 2021 and issued a mandamus instructing that Deuba be appointed Prime Minister within three days. Even Oli’s own supporters expressed dissent, claiming the dissolution violated the spirit of the Constitution, but he ignored them. Instead, he criticized the subsequent Deuba-led government as a “mandamus government.”

Ineffective nationalist card

No matter which coalition he leads, UML Chairman Oli plays the nationalist card. At one point, he was accused of being pro-India, but more recently, he has expressed serious confrontation with India. When India converted dissatisfaction over the new Constitution into a blockade, Oli strongly opposed it, which became his political capital. Political science professor Pokharel says, “During his first premiership, Oli’s stance against the Indian blockade became evidence that he could act decisively. That gave him political legitimacy and encouraged him to play the nationalist card more confidently.”

Alongside opposing the blockade, Oli’s transport agreement with China was considered a significant achievement. The agreement allows Nepal to conduct trade with third countries via four maritime routes and three dry ports in China. However, geographic difficulties and lack of infrastructure have prevented its full implementation.

During his second term, Oli intensified tensions with India, which had encroached on territory including Limpiyadhura. Under his initiative, Parliament unanimously issued a new map of the country. Shortly afterward, he met Samant Goel, head of India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), in Baluwatar, which tarnished his nationalist image. Director Ghimire says, “Oli appeared to lean toward China in his previous two terms. This time, he tried to balance relations between India and China.”

Deuba cannot live without power

Congress President Deuba is seasoned in the game of power. Having served as Prime Minister five times, he awaited another term. He has previously led various coalitions. In the past ten years, he led the government twice, both times with the support of Maoists and other parties. This time, he prepared to assume power with UML support.

Deuba became active in the anti-Panchayat movement around 1963. Before the restoration of multi-party democracy, he was imprisoned multiple times. After entering open politics, he developed a reputation as a leader willing to play any political game for power. During his time in jail, he was aligned with Krishna Prasad Bhattarai. When Girija Prasad Koirala was Prime Minister, Deuba served as Home Minister.

After Congress won a single majority in the 1991 elections, Koirala became Prime Minister. At that time, Deuba, as Home Minister, decided to purchase 20 vehicles for ministries. A former minister who was part of the cabinet recalls, “The vehicle dealer asked whose name to register for commission purposes. Deuba instructed that all 20 vehicles be registered under the Home Ministry’s name.” Such idealism later succumbed to greed for power, authority, and wealth. “It’s hard to believe that Deuba today is still the same person,” the former minister adds.

Deuba first became Prime Minister in 1995. His efforts to maintain a minority government are seen as distortions of parliamentary norms. He created jumbo cabinets to satisfy supporters, offered luxury benefits to MPs, organized trips to Thailand on government expenses, and oversaw buying and selling of parliamentary seats. Political analyst Jhalak Subedi says, “Deuba is one of the most infamous figures in Nepal’s parliamentary history.”

Deuba played a key role in moving Congress leadership away from the Koirala family. Among the second generation of leaders, Shailaja Acharya, Ramchandra Paudel, and Deuba were the most powerful. Acharya, Koirala’s niece, failed to rise to top leadership; Paudel avoided political risk, allowing Deuba to take charge.

Deuba became active in the anti-Panchayat movement around 1963. Before the restoration of multi-party democracy, he was imprisoned multiple times. After entering open politics, he developed a reputation as a leader willing to play any political game for power.

His actions while in power constantly raise questions about his commitment to democratic governance. Subedi adds that Deuba’s relationship with then-King Gyanendra was politically problematic. “Deuba represents Congress’s liberal democracy and pro-market policies. But his closeness to the King seriously questions his commitment to democracy,” he says.

In 2001 Deuba dissolved Parliament and announced election dates. However, failure to conduct elections on time led King Gyanendra to dismiss him. Upon returning as Prime Minister in 2004, Deuba claimed vindication from the Gorkhali monarchy. Yet, the King reclaimed power on February 1, 2005, imprisoning him and many other leaders.

For power, Deuba even split the party, creating the Nepali Congress (Democratic), also known as Royalist Congress, which later merged back into Congress. Min Bahadur Bishwakarma, a central committee member close to Deuba, says, “From political legacy and ideology to economic systems and organizational strategy, Congress remains in the position it has always been. President Deuba has not wavered.”

Deuba consistently appears as a devotee of power. Even when Congress shrank to 23 seats in 2017 elections under the first-past-the-post system, he did not take responsibility. He shifted blame, saying it was not solely his responsibility to win. Political analyst Wagle notes that Deuba’s belief that he is the institution, regardless of party size, has made his performance merely adequate.

Architect of instability: Dahal

Maoist Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal emerged into open politics after joining the peace process. Compared to the other two leaders, he has less experience in open political governance. However, he has been cleverer than Oli and Deuba in forming and dissolving governments.

Dahal first became Prime Minister in 2008 after the Maoists emerged as the largest party in the Constituent Assembly election but lasted only nine months due to his own mistakes. Since then, he has successfully become Prime Minister twice on the foundation of political instability.

Maoist Secretary Ram Karki says, “Top leaders may have read many things in books, but imitation comes from experience. The leaders experienced monarchical-style governance, so their exercise of power resembled monarchy. All parties looked different in name but had the same political culture and methods.”

For power, Deuba even split the party, creating the Nepali Congress (Democratic), also known as Royalist Congress, which later merged back into Congress.

This party won only 32 seats in the last election. Yet, Dahal managed to leverage the first and second largest parties to assume government leadership. Even after the promulgation of the new Constitution, this party, ranked third in Parliament, remained at the center of power. After the Constitution came into effect, the Maoist Centre was out of power only during the most recent Oli government.

Although Dahal held relatively few seats in Parliament, he took advantage of the rivalry and competition between the UML and Congress to seize opportunities to lead two governments. He became known as a political actor who quickly shifted parliamentary equations. Director Ghimire says, “Dahal applied guerrilla warfare strategies to parliamentary politics as well. His style involved pitting the two major parties against each other, splitting them, and then inserting himself into the resulting power vacuum to rule.”

Dahal appeared like a parasite in power politics. He could not survive alone; his existence depended on attaching himself to others. He would use people for his purposes and discard them afterward. During his first term, his inexperience prevented him from leading the country in a transformative way. He also failed to make the Constituent Assembly successful. While Prime Minister, he decided to dismiss the then-Army Chief Rookmangad Katwal—a decision that led to his own ousting.

After being sidelined due to the army chief issue, Dahal became Prime Minister in 2016 immediately after the Constitution was promulgated.

During that period, his focus was only on becoming and removing the Prime Minister. Dahal elevated figures such as Madhav Kumar Nepal, who had lost two elections, and then Chief Justice Khilraj Regmi, to positions of power.

Political analyst Wagle says, “Dahal’s character is power-oriented and authoritarian. Playing a game beyond his own capacity is characteristic of him. It benefits him personally but harms the country.”