KATHMANDU: It was the first time in Nepal’s history, on April 12, 1981, that a member of the royal family was targeted with the slogan “Murdabaad” (Down with) from a public playground.

At the time, it was customary for the National Sports Council (NSC) to have a royal patron. The first such patron of Nepali sports was King Mahendra’s brother, Prince Basundhara, who passed away in 1977. Following his death, King Birendra’s younger brother, Prince Dhirendra, assumed the role. Three years into his tenure as patron, the controversial incident occurred.

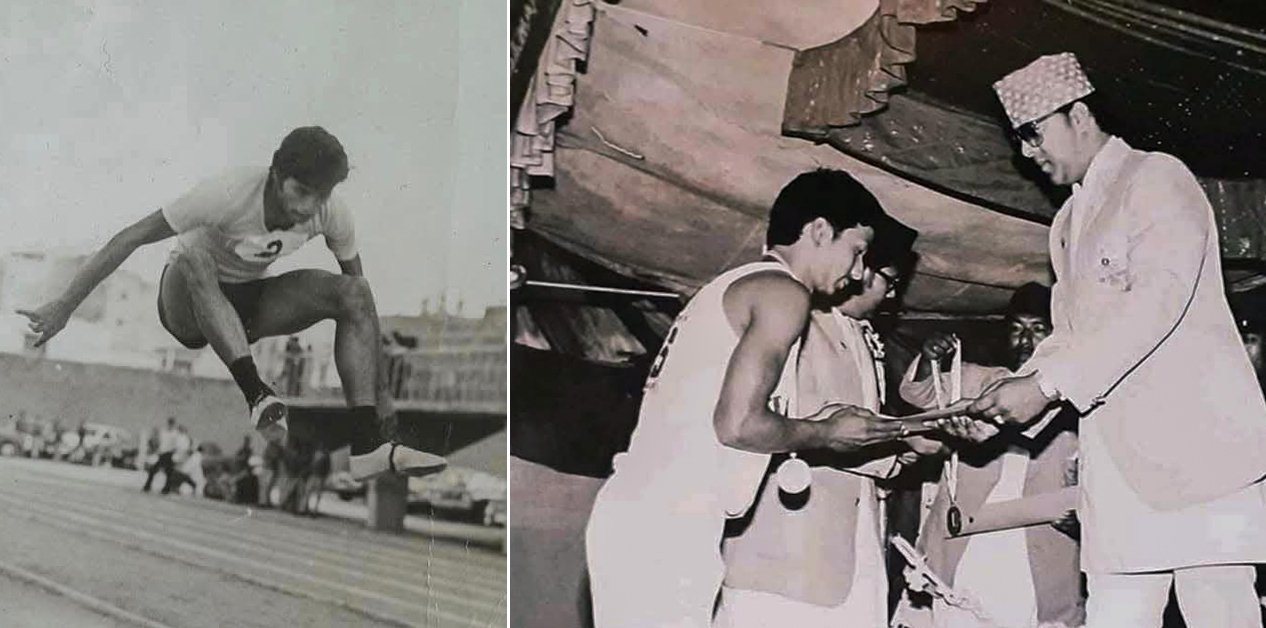

Athlete Narayan Yadav from Koshi Zone had already made a name for himself by winning a hat-trick of gold medals in the long jump, triple jump, and high jump. Riding high on his success, he was also entered in the 4x100m and 4x400m relay events.

Yadav’s relay team included stars like Jitendra Chaudhary, Binod Bista, and Pushparaj Ojha. Coach Bishwaprakash Thapa was confident this team would finally break Bagmati Zone’s long-standing dominance and make Koshi the new champion in the national athletics scene.

But no one could have predicted what happened next—what should have been a celebratory moment turned into one of the biggest scandals in Nepali sports history.

In the 4x100m relay, Narayan Yadav began the race for Koshi, while Raghuraj Wanta led for Bagmati. Unexpectedly, the referee disqualified Koshi’s team for a ‘false start’, a decision that triggered outrage. The dispute quickly escalated into chaos—and from the stands, the unthinkable slogan erupted: “Dhirendra Murdabaad!” (Down With Dhirendra)!

Renowned Nepali runner Baikuntha Manandhar. Photo: Shyam Chitrakar

Before the 4×100 meter relay began, Koshi and Bagmati were neck and neck in the medal tally—each with 8 golds and 6 silvers. The relay event would ultimately determine who would take home the championship. With Bagmati already having secured gold in the 4×400 meter relay and Koshi finishing second, the 4×100 meter race became a do-or-die match for Koshi.

But when Koshi was suddenly disqualified for a ‘false start’, the decision backfired spectacularly on the organizers, the Nepal Amateur Athletics Association. The grounds quickly descended into chaos, turning the prestigious national championship into a battleground.

Up until 1981, Bagmati had dominated national athletics, consistently winning thanks to superior training facilities and its status as the team from the capital. The athletes of Bagmati had an unmistakable edge. But this time, they were being fiercely challenged by a Mofusal (non-capital) team—Koshi, a rare and powerful shift in the competitive landscape. Unsurprisingly, most of the non-Bagmati teams rallied behind Koshi.

Under the Panchayat system, Nepal had been divided into five development regions and 14 zones, with all national sporting events organized at the zonal level. In the 20th National Athletics Championships, held in Kathmandu, 24 gold medals were up for grabs in the track and field category. Athletes from 11 zones—including Mechi, Koshi, Sagarmatha, Janakpur, Narayani, Bagmati, Gandaki, Lumbini, Dhaulagiri, Bheri, and Karnali—competed.

Furious over what they saw as blatant manipulation, Koshi decided to boycott the rest of the competition. In an unprecedented move, athletes staged a protest on the field—not just against the disqualification, but against Prince Dhirendra Shah, the patron of the National Sports Council. Their chant echoed through Tundikhel: “No to rigging! Down with Prince Dhirendra Shah!”

Athletes and officials from Mechi and Narayani joined in the protest, standing in solidarity with Koshi and intensifying the demonstration. It was a historic moment—the first time a member of the royal family had become the target of public dissent at a national sporting event.

Recalling the infamous incident, Baikuntha Manandhar—then a national athletics star—says he was forced to take matters into his own hands just days before the competition began:

“Two days before the event, no one had started building the track or marking the lanes with lime. I had no experience in track construction, but seeing no other option, I prepared it myself. I did it as best as I could. Naturally, there were many mistakes,” he stated.

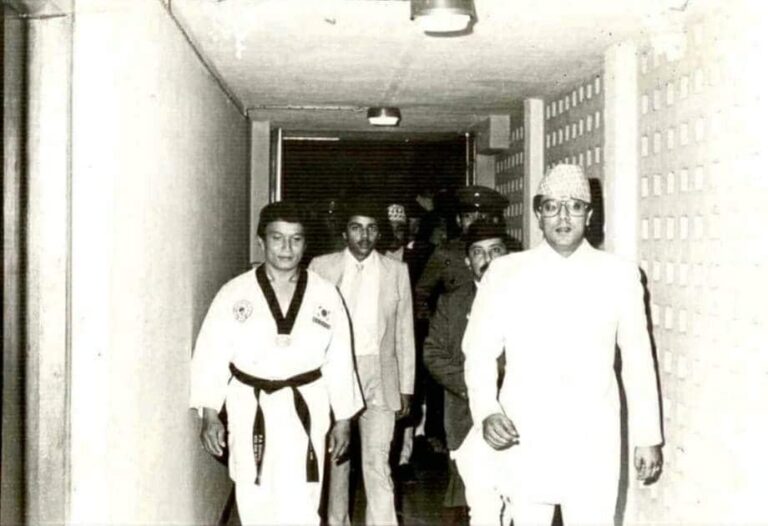

Prince Dhirendra with martial arts athlete P.A. Gurung. Photo Credit: P.A. Gurung’s Facebook

When technical questions began to surface after the controversial disqualification of Koshi’s relay team, then Member-Secretary of the National Sports Council Sharad Chandra Shah summoned Manandhar for clarification.

“I told him I wasn’t a technical person and had only stepped in because no one from the association took responsibility,” Manandhar recalls. “I expected disciplinary action. Instead, I was rewarded with Rs 1,000 for my initiative. It was unbelievable.”

That technical mishap—along with allegations of political bias and unfair officiating—led to the suspension of several key athletes, including some of Nepal’s rising sports stars. Among them were Narayan Yadav, Pushpa Bhatta, Ganga Magar, Pushparaj Ojha, Duryodhanraj Rai, Rajbhakta Pradhananga, and Atmaram Upreti—all representing Koshi Zone.

In the 20th National Athletics Championship, these athletes had made a significant mark: Narayan Yadav won three golds, Pushpa Bhatta won two, Rajbhakta, Duryodhan, and Ganga secured one gold each.

But due to the blanket ban imposed after the relay incident, none of them were allowed to compete in the first-ever major national sports competition held in Kathmandu six months later. Their absence was deeply felt—Koshi, once a strong title contender, managed to win only two gold medals.

“It was a great misfortune for us,” says coach Bishwa Prakash Thapa, adding, “Just six months earlier, we were neck and neck with Bagmati. But by the next championship, we had dropped to fifth place.”

The Mechi Zone also suffered. Urmila Oli, the gold medalist in the 100-meter sprint, was banned despite her outstanding performance. She had beaten Pushpa Bhatta (silver) and Salina Bhattarai from Bagmati (bronze). Oli also secured silver medals in the 200 meters and women’s long jump. In her absence—and without several other key athletes—Mechi’s performance declined, dropping from third to fifth place in the next national event, despite winning three gold medals in the sprints.

The consequences of the disciplinary actions were long-lasting. Many of the banned athletes never returned to competitive sports, their careers cut short by a scandal rooted not just in technical error but also in the turbulent political climate of the time.