KATHMANDU: A unique example of how cricket has connected politicians and journalists in India is the annual cricket tournament held in New Delhi between parliamentary party leaders and journalists. This tournament has been organized since the time of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

In 1990, when I visited New Delhi on business, the tournament happened to be underway. At that time, Madhavrao Scindia, an influential MP from Madhya Pradesh, had just been appointed president of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI). I had already met him. He was married to Madhavi, the daughter of Shumsher Rana, who was close to our family.

While the tournament was going on, I went to the Feroz Shah Kotla Stadium in Delhi to meet him. He said, “Now we will not play cricket with Pakistan in Sharjah (UAE). There has been a lot of protest in India.”

Cricket tournaments had been held between India and Pakistan in Sharjah since the 1980s. However, India usually lost those tournaments. As a result, the BCCI was being heavily criticized—from Parliament House to the streets.

During our conversation, Madhavrao made an unexpected proposal: “We are looking for a neutral place. Are you interested?”

As soon as I heard his proposal, a light bulb went on in my mind. Without thinking, I replied, “We are interested.”

He then asked me to meet Subhash Chandra, the owner of ZTV, immediately. Chandra was staying in a suite at the Taj Palace Hotel. Madhav provided me with the room number.

After the game that day, I went straight to the hotel to meet Chandra. He was sitting alone in a grand room at the Taj Palace. I introduced myself. When I mentioned that Madhavrao Scindia had sent me, his tone shifted noticeably. He began speaking with more enthusiasm: “That’s it, the BCCI is looking for a neutral place. I think Malaysia and Nepal would be suitable. Do you have a suitable ground to play cricket? We are ready to build a stadium.”

I didn’t fully understand the matter until I went to meet him. I had assumed that the BCCI must have taken the initiative. However, my understanding turned out to be the opposite. ZTV was preparing to launch a campaign to build a suitable ground for Indian cricket.

Before Chandra’s question could even settle, I responded, “Whatever it is, there are empty grounds everywhere in Kathmandu.”

How many structures had been built in Kathmandu 35 years ago? Everything was open. There weren’t houses built all around like there are now.

He was impressed by my words. Madhav Rao also wanted a ground for Indian cricket to be built in a neutral location like Nepal. After all, Nepal was his in-laws’ country. He had fled to Kathmandu when the ‘emergency’ was imposed in India in 1975.

After a positive discussion with Subhash Chandra, I quickly returned to Kathmandu. Within a few days, he sent his brother Laxmi Chandra. Along with Laxmi Chandra, a journalist from the Times of India, Tiwari, was also part of the team sent to assess the ground.

How many structures had been built in Kathmandu 35 years ago? Everything was open. There weren’t houses built all around like there are now.

But finding a ground for cricket turned out to be more difficult than expected. I had thought, how hard could it be to find a cricket ground in Kathmandu, where there weren’t many houses? Yet no matter how much I searched, I couldn’t find a suitable place to build one.

At the time, the National Construction Company Nepal (NCCN) office was located in Halchowk in Kathmandu — now the headquarters of the Armed Police Force (APF). Since that company was about to be liquidated, we assumed that the ground in Halchowk would be suitable for cricket.

The sewage pond in Chobhar was also considered as another option. For this, Chairman Jayakumar Nath Shah began lobbying at the royal palace. I was working at the local level. But despite all the lobbying, we couldn’t secure a ground.

Laxmi Chandra and the Indian journalists returned to Delhi disappointed. It became a matter of shame for us.

The next year after this incident, India announced that it would no longer play cricket against Pakistan in Sharjah. Our anxiety grew even more.

In 1992, I met Mangalsiddhi Manandhar at a party. At that time, he was teaching at Tribhuvan University and had not yet become a minister. He was also a former cricket and football player. We had studied in the same batch at Tribhuvan University.

When he saw my downcast expression at the party, he asked, “What happened, Binay? Why are you sad?”

I was still feeling guilty about not being able to build a cricket ground in Kathmandu two years earlier. My heart was pounding with regret over having lost such a big opportunity from ZTV. I said, “Look, man, we missed such a great chance to build a cricket ground.”

After hearing this, he laughed and said, “Why are you upset over such a small thing? We already have a ground at Tribhuvan University. We can use that!”

Suddenly, I remembered the football ground inside Tribhuvan University. The same field—now an international cricket ground—was previously used for football. A SAARC-level football tournament had even been hosted there some time ago. Mangalsiddhi said, “Come tomorrow, I’ll show you the place.”

The next morning, I went to the TU football ground. The field seemed a bit small. After inspecting it from all sides, I told him, “I can’t make the decision alone. I need to ask ZTV.”

Even though the ground was small, I was happy we had found something. But I was also worried that ZTV might reject it.

I immediately informed the ZTV team in India. They sent a curator from Punjab to inspect the ground. After examining it, he said, “It’s okay.”

That was all we needed to hear! Everyone was thrilled. It was now official—Nepal was going to have its first international cricket ground.

However, even after that, one problem remained. There was no agreement between Tribhuvan University and the Cricket Association of Nepal (CAN).

Later, with Mangalsiddhi’s initiative, a three-member committee was formed consisting of him, me, and the president of the Tribhuvan University Students’ Union. That committee signed a five-year agreement with TU.

I had warned that since ZTV was making such a large investment to build the stadium, a five-year agreement might not be enough for them. But Mangalsiddhi reassured me. He said, “Five years is fine for now. Once the infrastructure is built, who’s going to tell them to pack up and leave?”

I found his logic convincing. I explained the same reasoning to ZTV, and they agreed. After that, full-scale construction began at the TU ground.

Mangalsiddhi’s initiative, a three-member committee was formed consisting of him, me, and the president of the Tribhuvan University Students’ Union. That committee signed a five-year agreement with TU.

The Road Department arranged everything—from bulldozers to threading machines. ZTV built everything from the dressing rooms to the VIP lounge on the end side of the ground. It took about two years to complete the full development.

During this time, ZTV assembled three teams: India, Pakistan, and a World XI. The World XI was composed of veteran players from the West Indies, New Zealand, Australia, England, South Africa, and Sri Lanka.

The Tempo World Legend Cup tournament—featuring these teams—kicked off in May 1999 at the Tribhuvan University ground.

The Indian veteran cricket team, led by Kapil Dev—the captain who had led India to its first World Cup victory in 1983—came to Nepal to compete in the tournament. Similarly, Pakistan’s veteran team, captained by the world-renowned leg-spinner Abdul Qadir, and the ‘Rest of the World Veterans’ team, led by former West Indies wicketkeeper Derek Murray, also participated.

This tournament, which brought together legendary players from across the globe, introduced Nepal to international cricket for the very first time. The Indian veterans, under Kapil Dev’s leadership, emerged as the tournament winners. The then Crown Prince Dipendra graced the event and presented the prizes.

The tournament was broadcast live by Star Sports TV, with … providing commentary. Nepal Television also had the opportunity to air the matches live. We had convinced ZTV that if cricket were to gain popularity in Nepal, live broadcasting on Nepali channels was essential. They agreed, allowing Nepal Television to broadcast the tournament without any investment.

Heads of state from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and several other countries traveled to Kathmandu to watch this GTV-organized event. During the Asian Cricket Council (ACC) meeting held at Hotel Yak and Yeti, representatives from all participating nations praised Nepal’s growing cricket culture and acknowledged Kathmandu’s suitability as a ‘neutral venue’.

After upgrading the Tribhuvan University stadium to international standards, ZTV had even bigger ambitions for Nepal. They planned to bring top teams like India, Pakistan, Australia, and the West Indies to compete in future tournaments here.

They were also campaigning to launch a dedicated sports channel, Z-Sports. During the ‘Tempo World Legend Cup,’ banners promoting Z-Sports were displayed prominently at the stadium.

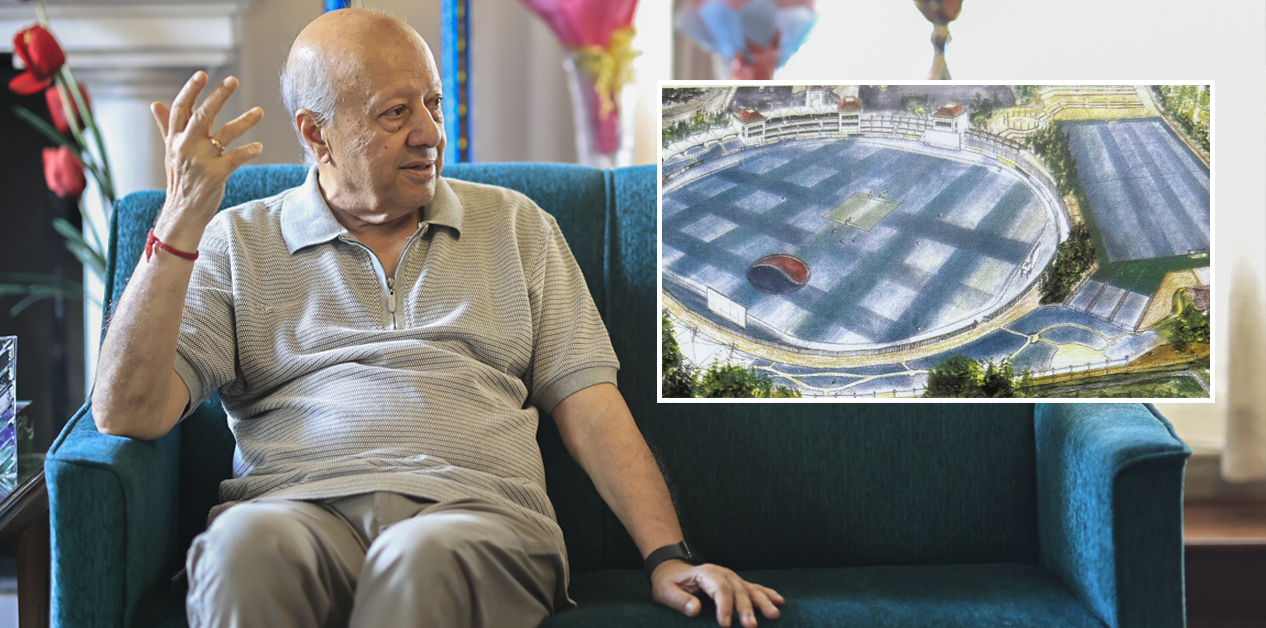

Following the successful conclusion of the ‘Tempo World Legend Cup,’ ZTV owner Subhash Chandra was elated. He announced plans to employ Nepali architects to further beautify the Tribhuvan University stadium to meet international standards. A model was even prepared for this project.

The tournament was broadcast live by Star Sports TV, with … providing commentary. Nepal Television also had the opportunity to air the matches live. We had convinced ZTV that if cricket were to gain popularity in Nepal, live broadcasting on Nepali channels was essential. They agreed, allowing Nepal Television to broadcast the tournament without any investment.

While ZTV was active in Nepal, I became the president of the Cricket Association of Nepal (CAN) in 2005. By then, our five-year contract with Tribhuvan University had expired and was yet to be renewed. The university’s vice-chancellor was Nabin Jung Rana, son of the celebrated theater artist Balkrishna Sam. I had an old friendship with him, and he was a former badminton player.

Together with Sriharsha Koirala, son of BP Koirala and then vice-president of CAN, I visited the university to meet Nabin Jung. We successfully convinced him, and the contract for the TU ground was extended for 20 years. We agreed to pay the university eight hundred thousand rupees annually for ground usage.

ZTV was excited by the contract extension and began planning to build a full-fledged stadium. However, at this time, Nepal’s Maoist insurgency was at its peak. The Maoists targeted development projects involving Indian investment.

Alarmed by the political unrest, ZTV abruptly announced, “We have withdrawn from the stadium-building plan in Nepal.”

We tried repeatedly to persuade them to reconsider and even engaged the Indian embassy. But with the country’s unstable atmosphere, their decision stood firm. Despite all efforts, they refused to return.

Thus, the promising cricket initiative that had begun with Madhavrao Scindia’s vision ultimately collapsed, causing a significant setback for Nepali cricket.

(Based on a conversation between Nabin Aryal and former President of the Cricket Association of Nepal, Binayraj Pandey)