Preventing foreign travel violates constitutional rights and international treaties

KATHMANDU: On the night of September 29, 2024, 40-year-old Bishnumaya Sherpa (name changed) was waiting in the departure lobby at Tribhuvan International Airport to complete the check-in and boarding process. She had her ticket for Dubai, passport, and visa in hand, but an immigration officer stopped her.

She was questioned on suspicion that her documents were fake and was ultimately turned back from the airport. Along with her, the immigration office handed over 61 other women to the Nepal Police’s Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau.

Sherpa complained, “Sisters from my village have already reached Dubai with similar documents. Why was I stopped?” Her question highlighted the unequal treatment carried out in the name of regulations.

A similar experience was faced by Manprasad Adhikari (name changed) from Morang. In June 2024), he and five friends went to Romania. Their plan was simple: travel first, work if possible, otherwise return.

However, immigration suspicion and questioning nearly ruined their plans. Officers asked, “Who will you stay with in Romania? Where will you stay?” Unable to give satisfactory answers, they were detained by immigration. But then the story took a turn. They contacted an agent in Delhi, the connection was activated, and with coordination from a Nepali agent, Adhikari and his friends were allowed to pass. Immigration suspicion did not stop them.

At Tribhuvan International Airport, many Nepali citizens carrying passports, visas, and tickets are stopped and harassed purely based on suspicion. Since 2022, 25,160 Nepalis on visit visas have been turned back. In 2022 alone, 4,293 travelers were sent back. This rose to 4,883 in 2023, 9,005 in 2024, and from January to September 2025, 6,979 were turned back.

Reasons given for turning people back include “document mismatch” or “suspicious visa purpose”. Such judgments are made by immigration officers based on assumptions, not under any legal provision.

The Constitution guarantees freedom of movement for citizens, but the immigration department curtails this right under various pretexts. This practice violates Article 16(1), which guarantees the right to live with dignity, Article 17(1), which ensures personal freedom, and Article 18, which guarantees equality.

Immigration appears to target those going to Gulf countries such as Kuwait, Oman, UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Their justification is that Nepalis on visit visas often end up working abroad, creating labor insecurity and risks, which is not a valid argument. It falls outside the jurisdiction of immigration. Embassies are tasked with assisting citizens facing labor risks abroad, not immigration officers.

Om Prakash Aryal, speaking to Nepal News before becoming Home Minister, asked: “Not everyone on a visit visa ends up as a slave. How much irreparable harm occurs when all such people are targeted?” The primary responsibility to prevent abuses in visit visas now rests with Aryal, as the policy decisions for addressing obstacles in visit visas lie in his hands.

The enforcement of visit visa rules is also discriminatory. Women are disproportionately targeted, and immigration officers harass them with questions. Those traveling to Gulf countries face even greater difficulties, with officers asking, “What is the purpose of travel? Are you going to work?” before turning them back.

Human rights violations are evident. Mihir Thakur, member of the National Human Rights Commission, says, “It is not just a human rights violation; it involves equality issues and human trafficking concerns. We are conducting a serious study of the visit visa issue.”

Passport and Immigration Act ridiculed

The passport and immigration laws are being mocked. The Passport Act, 2019, Section 2(e), defines a passport as the machine-readable, electronic, or biometric passport issued by the Government of Nepal for foreign travel, and Section 3 requires citizens to carry a valid passport for travel. The law imposes no other conditions for foreign travel.

The Immigration Act, 1992, regulates inbound and outbound travel. Section 2(ga) defines a passport as any travel document issued by a government or UN laissez-passer, and includes permissions for travel.

Under the Immigration Rules, 1994, and the Immigration Procedures, 2065, officers follow Procedure 3.1 when granting departure permission. Officers check passports, departure forms, and boarding passes, validate visas for countries that do not allow visa-on-arrival, and verify if a person is prohibited from leaving. If all documents are correct, they affix a departure sticker and stamp.

For tourists or other short-term travelers, valid passports of at least six months and a visa for the travel purpose are required. Officers also check round-trip tickets, letters from sponsors detailing expenses, or proof of at least USD 500 in foreign currency.

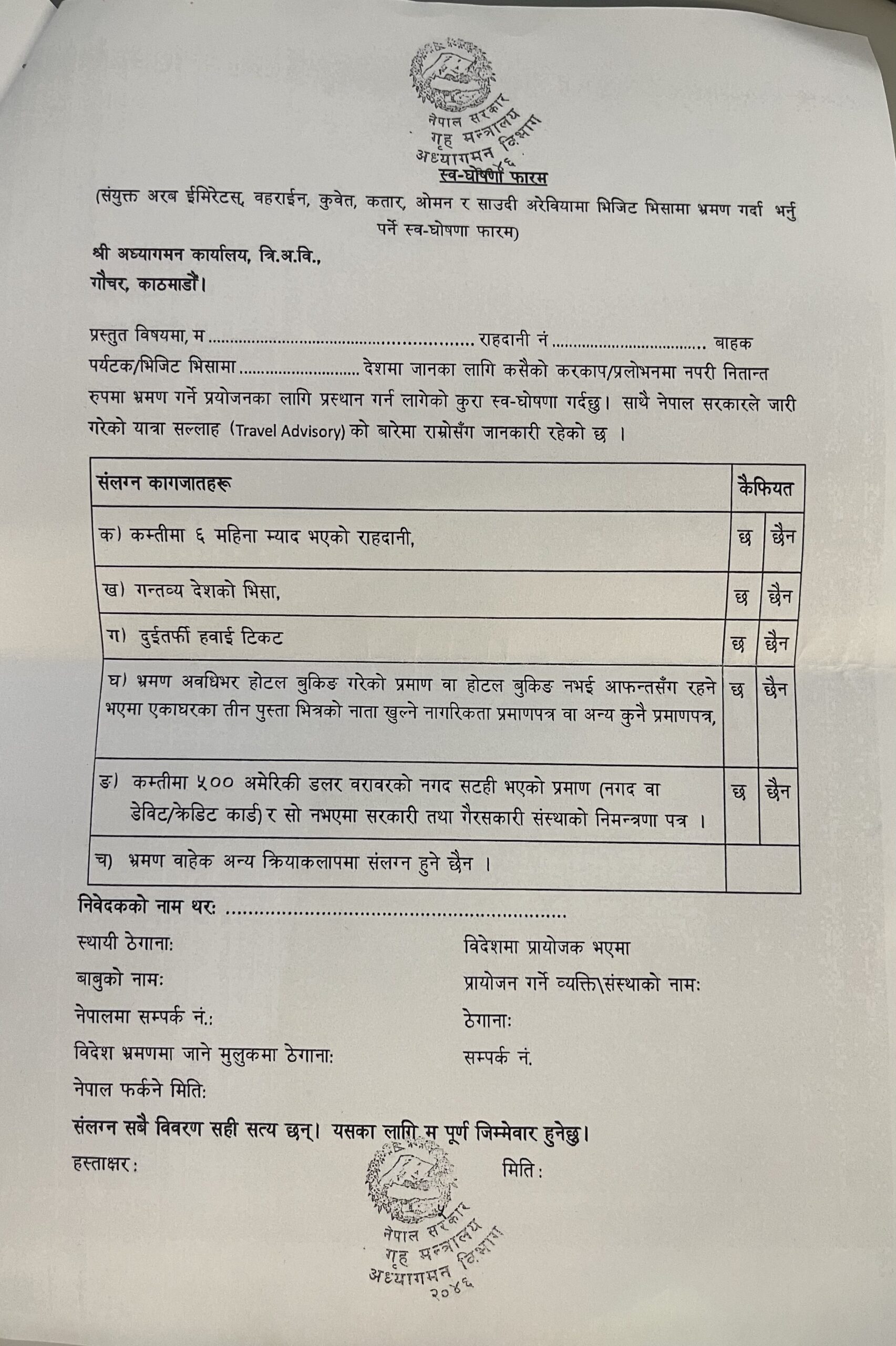

In addition, on January 24, 2024, immigration issued a notice detailing documents required for visit and tourist visas. Proof of hotel booking or staying with relatives (with relationship certificates within three generations) is needed. Travelers to the Gulf countries must also fill out a self-declaration form, with the burden of proof on the traveler.

See the self-declaration form

Immigration officers have the right to withhold departure if documents are suspicious, but stopping travel even with a valid visa is ongoing practice. According to Rule 14 of the Immigration Rules, officers may prevent departure if a traveler lacks a valid passport or visa, or if an authorized officer sends reasoned instructions to block travel.Similarly, Section 12 of the Passport Act, 2019, allows passports to be blocked if the person is involved in corruption, human trafficking, kidnapping, drugs, illegal arms trade, organized crime, terrorism, or is blacklisted for unpaid loans.

In practice, immigration officers exercise discretionary power based on suspicion or assumption, stopping visit visa holders without valid reason. Advocates like Aryal argue this needs objective grounds, and compensation must be available for harm caused.

Director General Ramchandra Tiwari acknowledges: “Yes, visit visas should be facilitated. Questions have arisen about restrictions we imposed. If we simplify the process, it becomes easier; making it complicated increases manipulation.” He admits immigration has not clarified its role. “It’s not only us stopping people. Sometimes customs and the airport also stop them, but all blame comes to us,” he complains.

When can immigration authorities deny departure?

Globally, immigration scrutinizes arrivals, not departures. In Nepal, the government tightens controls on departing citizens. Once the visa is issued, the state has the duty to allow smooth travel. Immigration mainly targets Gulf-bound travelers, not those going to Europe. Unless citizens are stopped at the airport, the problem persists, prompting some Nepalis to travel through Indian border points to Delhi to reach other countries.

While working on a visit visa is illegal, millions of Nepalis work abroad on visit visas, and the state does not track them. Aryal asks: “If it’s illegal, why didn’t Nepal intervene to send them back? Why didn’t the embassies address this?”

Even Supreme Court rulings support unrestricted travel. In a 14 November 29, 2019 decision, the court allowed Lenin Bista, a former Maoist combatant, to travel to Bangkok after being stopped at the airport by order of the Home Minister. The court stated the restriction violated Articles 17, 18, and 20 of the Constitution, emphasizing the need to protect citizen rights against illegal restrictions.

Judges Anand Mohan Bhattarai and Kumar Regmi noted that stopping Bista illegally deprived citizens of their rights. The ruling clarified that citizens who have completed all legal formalities cannot be illegally prevented from traveling, and governments must provide clear guidance to protect citizen rights. The court emphasized personal liberty as essential to human dignity, stating that restrictions on such rights are unacceptable. It further observed that freedom, equality, respect, inclusivity, and participation are inherent, inalienable rights, and respecting them is the state’s foremost duty.

Human trafficking concerns are intertwined with visit visa “arrangements” at airports. In recent years, there have been allegations of organized money collection from Nepalis traveling on visit visas, and on May 21, 2025, Joint Secretary of Immigration Department Tirtharaj Bhattarai was taken into custody by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA).

International Terminal at TIA. Photo: Bikram Rai/Nepal News

Funds collected allegedly reached then-Home Minister Ramesh Lekhak. A high-level study committee led by former Secretary Shankardas Bairagi submitted a report to the government on September 25, 2025, but the Ministry has not made it public.

Investigations also revealed that immigration officers were using visit visa documents to solicit bribes. In December 2023, officers including Narbir Khadka, Hom Pokharel, and Arbin Yadav were arrested for colluding with agents to produce fake documents and send people abroad.

Applicants had to show grade 12 certificates and Rs 200,000 in a bank account. Each day, 50–60 people flew to Gulf countries, paying bribes of Rs 25,000–60,000 per person. The Home Ministry later amended the documents, removing the grade 12 certificate requirement, though proposals continue to be debated.

After the arrests, physical altercations occurred between police and immigration staff at the airport. Police reportedly beat officers for misconduct on January 26, 2024, and since then, the police have largely refrained from interfering with immigration work, focusing only on security. The airport now has multiple security agencies, but they do not intervene in visa matters.

The Immigration Department has two types of personnel—experienced and educated competitive youth. Sending well-qualified, English-speaking, motivated staff could resolve many of the problems. However, investigations indicate connections (“settings”) exist between immigration and airlines, allowing certain applicants to pass without scrutiny.

Migrant workers on labor visas face lower risks, as employment and repatriation guarantees exist. In contrast, visit visa holders bear risks once abroad, and manpower agencies’ responsibility ends once the traveler boards the plane.

Despite strict controls, foreign travel on visit visas has been rising steadily. In 2022, 177,310 Nepalis traveled abroad on visit visas, increasing to 204,535 in 2023, 276,624 in 2024, and 172,287 from January to September 2025.

Obtaining a visit visa requires understanding that it is a short-term visa for tourism, visiting relatives, medical treatment, business, or short-term study/training. Relatives abroad or inviting institutions can initiate the process. Uninformed citizens often approach manpower agencies, travel agencies, or consultancies, though government offices do not process visit visas.

Many foreign companies or embassies can assist directly, but most applicants rely on agencies, whose official role is unclear.

Even ten years after the Constitution, the Immigration Act remains outdated. The department continues under old laws, causing citizens’ freedoms to be curtailed. “A bill to update and simplify the Immigration Act was sent to the Cabinet,” says Tikarama Dhakal, information officer.

Before passage, the House was dissolved, halting progress. The previous Immigration Bill, 2019, filed in the National Assembly, was returned in 2023. Meanwhile, the government continues to add hurdles to visit visas, complicating citizens’ travel.